The Seventh Nizam : the Claim for Independence

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Authority, Knowledge and Practice in Unani Tibb in India, C. 1890

Authority, Knowledge and Practice in UnaniTibb in India, c. 1890 -1930 Guy Nicolas Anthony Attewell Dissertation submitted in partial fulfilment for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, School of Oriental and African Studies, University of London ProQuest Number: 10673235 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a com plete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. uest ProQuest 10673235 Published by ProQuest LLC(2017). Copyright of the Dissertation is held by the Author. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States C ode Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. ProQuest LLC. 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106- 1346 Abstract This thesis breaks away from the prevailing notion of unanitibb as a ‘system’ of medicine by drawing attention to some key arenas in which unani practice was reinvented in the early twentieth century. Specialist and non-specialist media have projected unani tibb as a seamless continuation of Galenic and later West Asian ‘Islamic’ elaborations. In this thesis unani Jibb in early twentieth-century India is understood as a loosely conjoined set of healing practices which all drew, to various extents, on the understanding of the body as a site for the interplay of elemental forces, processes and fluids (humours). The thesis shows that in early twentieth-century unani ///)/; the boundaries between humoral, moral, religious and biomedical ideas were porous, fracturing the realities of unani practice beyond interpretations of suffering derived from a solely humoral perspective. -

03404349.Pdf

UA MIGRATION AND DEVELOPMENT STUDY GROUP Jagdish M. Bhagwati Nazli Choucri Wayne A. Cornelius John R. Harris Michael J. Piore Rosemarie S. Rogers Myron Weiner a ........ .................. ..... .......... C/77-5 INTERNAL MIGRATION POLICIES IN AN INDIAN STATE: A CASE STUDY OF THE MULKI RULES IN HYDERABAD AND ANDHRA K.V. Narayana Rao Migration and Development Study Group Center for International Studies Massachusetts Institute of Technology Cambridge, Massachusetts 02139 August 1977 Preface by Myron Weiner This study by Dr. K.V. Narayana Rao, a political scientist and Deputy Director of the National Institute of Community Development in Hyderabad who has specialized in the study of Andhra Pradesh politics, examines one of the earliest and most enduring attempts by a state government in India to influence the patterns of internal migration. The policy of intervention began in 1868 when the traditional ruler of Hyderabad State initiated steps to ensure that local people (or as they are called in Urdu, mulkis) would be given preferences in employment in the administrative services, a policy that continues, in a more complex form, to the present day. A high rate of population growth for the past two decades, a rapid expansion in education, and a low rate of industrial growth have combined to create a major problem of scarce employment opportunities in Andhra Pradesh as in most of India and, indeed, in many countries in the third world. It is not surprising therefore that there should be political pressures for controlling the labor market by those social classes in the urban areas that are best equipped to exercise political power. -

H-8/4 Islamabad Federal Board of Intermediate And

FEDERAL BOARD OF INTERMEDIATE AND SECONDARY EDUCATION H-8/4 ISLAMABAD Date: 18/12/2015 Computer Section(G) Inst. Code: 7766 Inst. Name: PAKISTAN INTERNATIONAL SCHOOL-TABUK, MADINAH ROAD, AL BASATEEN RESTAURANT AREA, TABUK, KINGDOM OF SAUDI S. No. STUDENT NAME FATHER NAME GENDER REG. No. 1 MAAZ SALEEM MALIK MOHD. SALEEM MALIK MALE 1777663001 2 MUHAMMAD ABDULLAH KHAWAJA JAMSHED MALIK MALE 1777663002 3 OSAMA BIN SAJJAD SAJJAD AHMED KHAN MALE 1777663003 4 SYED AHSAN AZIZ SYED AZIZ UDDIN MALE 1777663004 5 TALHA INAM INAM UL HAQ MALE 1777663005 6 ZAKIR SHIREEN SHIREEN MUHAMMAD MALE 1777663006 7 ALINA MOHAMMAD MOHAMMAD ANWAR UL HAQ FEMALE 1777664001 8 ARFA MUNIR MUNIR AHMED FEMALE 1777664002 9 KALSOOM KHAIR MOHMMAD KHAIR MOHAMMAD FEMALE 1777664003 10 MISHGAN DAYAM HUSSAIN MIAN DAYAM HUSSAIN FEMALE 1777664004 Page # 1 FEDERAL BOARD OF INTERMEDIATE AND SECONDARY EDUCATION H-8/4 ISLAMABAD Date: 18/12/2015 Computer Section(G) Inst. Code: 7765 Inst. Name: Pakistan Urdu School, Isa Town, Bahrain. S. No. STUDENT NAME FATHER NAME GENDER REG. No. 1 ABDULLA JAVED IQBAL NAZIR AHMED KHAN JAVED IQBAL NAZIR AHMED KHAN MALE 1777653001 2 ABDULLAH AFZAL KHAN AFZAL KHAN MALE 1777653002 3 ABDULLAH FAISAL FAISAL MURTAZA MALE 1777653003 4 ABDULLAH HAMEED ABDUL HAMEED MALE 1777653004 5 ABDULLAH SAFDAR ALI ALAMDIN SADER DINSAFDAR CHOUDHARY ALI ALAMDIN SADER DIN CHOUDHARY MALE 1777653005 6 ABDUR REHMAN AFZAL BAIG MOHAMMAD AFZAL BAIG MALE 1777653006 7 ADNAN MOHAMMAD ASHRAF KH.HIDAYAT KH.MOREMOHAMMAD KH. ASHRAF KHAN HIDAYAT KH.MORE KH.MALE 1777653007 8 AFFAN MOHAMMAD IMRAN SHAIKH MOHAMMADMOHAMMAD Y.M. UDIN IMRAN SHAIKH MOHAMMAD YOUNESMALE M. -

The Book Only

TEXT CROSS WITHIN THE BOOK ONLY ~n<00 OU 158086 >m Hyderabad State List of Leading Officials, Nobles and Personages HYDERABAD RESIDENCY GOVERNMENT PRESS 1987. List of A ia from whom Government of India Publications are available, Provincial Government Book Depots. , Government Press, Mount Road, Madras. BonnAY j Superintendent, Government Printing and Stationery, Queens Eoad, Bombay. BIND i- Manager, Bind Govt. Book Depot and Record Office, Karachi (Sadarj. UNITED FBOTIHCBS {Superintendent, Government Press, Allahabad. PusJAB: Superintendent, Government Printing, Punjab, Lahore. BCBMA Superintendent, Government Printing, Burma, Ban goon. CBNTBAL PBOVINCKB : Superiatendent, Gorerninent Printing, Central Provinces, Nagpur. ABAM Superintendent, As*am Secretariat Press, Shillong. BIHAB : Superintendent, Government Printing, P. 0. Gulzarbagb, Patna. NOBTH-WKST FKDNTIER PBaviNCfi; -Manager, Government Printing and Stationery, Peshawar. OBMSA:-Press Officer, Secretariat, Cuttack. (b) Private Booksellers. Advanl Bros., P. 0. Box 100, Cawnpore. Malhotra & Co., Post Box No. 01, Lahore. Messrs. U. P. Aero Stores. Karachi.* Mluutva Book Shop, Anarkali Street, Lahore. BantMya & Co.. Ltd., Station Goad, Ajmer. Modern Bjok Depot, Baiar Road,8lalkot Cantonment. Bengal Flying Club, Dnm Dum Cantonment.* Modern Book Depot, Napier Road, Jnllnndur Cantonment. Bbawnanl & Sons. New Delhi. Mohanlal Dossabhai Bhah. Rajkot. Book Company, Calcutta. Nandkishore & Bros., Chowk, Beaares City. New Booklover's Resort, Taikad, Trivnndram, South India. Book Co., "Kitab Mahal "198, Hornby Road, Bom- bay. Burma Hook Club, Ltd., Rangoon. Newman & Co., Ltd., Calcutta, Messrs. W. Batterworth & Co., (India), Ltd.. Calcutta. Oxford Book and Stationery Company, Delhi, Laboie. Careers : Mohini Lahore. Road, bimla, Meernl and Calcutta. & Baoharam Calcutta. Cbatterjee Co., 3. Chatterjee Lane, Parikh & Co., Baroda, Messrs. B. Choke; vertty. Chatterjee & Co., Ltd , 13, College Square. -

1 Bio-Data Name: Dr. Md. Gayasuddin Prof. & Head, Department of Urdu

1 Bio-data Name: Dr. Md. Gayasuddin Prof. & Head, Department of Urdu Dr.Babasaheb Ambedkar Marathwada University Aurangabad- 431004, Maharashtra (India) Academic Qualifications: Ph.D. : 1991 A.M.U. (A Comparative Study of the Problems of Communalism in Urdu and Hindi Short Stories 1948-78) M.Phil. :1988 A.M.U. (A Critical Study of the Short Stories of Krishna Chandra) M.A. :1984 A.M.U. 1st Class 1st Position Gold Medal B.A.(Hons.) :1980 L.N.M.U. 1st Division (Darbhanga) Teaching Experience: : 28 Years Assistant Professor :1988-1998 (10 years)University of Pune, Maharashtra (India) Associate Professor (CAS) :1998-2006 (7 years)University of Pune, Maharashtra (India) Professor (Direct) : 2006 - till date (11 years completed) Dr. Babasaheb Ambedkar Marathwada University, Aurangabad, Maharashtra (India) Teaching Experience Classwise: U.G. 17 Years P.G. 28 Years M.Phil. 08 Years Administrative Experience: 17 years as Head of Departments Research Experience: 28 Years Field of Specialization: Fiction Publications: 2 Books Published:12 01.”Zawal-e- Adam-e- Khaki” (Novel) Pages:388 ISBN No. 978-93-5073-090-4 published from Educational Publishing House Delhi in 2013. 02. “Azab-e-Danish-e-Hazir” (Novel) Pages: 575 ISBN No. 978-93-5073-607-04 published from Educational Publishing House Delhi in 2015 03. “Sohbat-e-Peer Hindi” (Novel) Pages:150 ISBN No. published from Educational Publishing House, Delhi in 2017 04. “Qissa-e- Roz-o-Shab” (Short Stories) Pages: 250 ISBN:978-93-86285 published from Educational Publishing House, Delhi in 2016. 05.”Firqawariyat Aur Urdu Hindi Afsana” (Criticism & Research) Pages:448 ISBN No.81-6232-83-4 published from Educational Publishing House Delhi in 1999. -

Urdu in Hyderabad State*

tariq rahman Urdu in Hyderabad State* The state of Hyderabad was carved out in 1724 by the Asif Jahis (Āṣif Jāhīs), the governors of the Mughal emperors in the Deccan, when they became powerful enough to set themselves up as rulers in their own right. The Nizams1ófrom Mīr Qamruíd-Dīn Khān (1724ñ48) until the sixth ruler of the house Mīr Maḥbūb ʿAlī Khān (1869ñ1911)óused Persian as their court language, in common with the prevailing fashion of their times, though they spoke Urdu at home. Persian was, however, replaced by Urdu in some domains of power, such as law courts, administration and education, toward the end of the nineteenth century. The focus of this article is on the manner in which this transition took place. This phenomenon, which may be called the ìUrduizationî of the state, had important consequences. Besides the historical construction of events, an attempt will be made to understand these consequences: the link of ìUrduizationî with power, the construction of Muslim identity, and socio- economic class. Moreover, the effect of ìUrduizationî on the local languages of Hyderabad will also be touched on. *The author is grateful to the Higher Education Commission of Pakistan for a grant to carry out research for this article in India. 1The Nizams who actually ruled were the first seven; the last in the line carried the title until 1971 but did not rule: 1) Mīr Qamaruíd-Dīn Khān Niāmuíl- Mulk Āṣaf Jāh I (r. 1724–48); 2) Mīr Niām ʿAlī Khān Āṣaf Jāh II (r. 1762–1803); 3) Mīr Akbar ʿAlī Khān Sikandar Jāh III (r. -

Regional Imbalance in the Indian State of Andhra Pradesh with Special Reference to Telengana

REGIONAL IMBALANCE IN THE INDIAN STATE OF ANDHRA PRADESH WITH SPECIAL REFERENCE TO TELENGANA A Dissertation submitted to the Tilak Maharashtra University Towards the Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of MASTER OF PHILOSOPHY IN POLITICAL SCIENCE Submitted by: Supervised by: Robinson. Undrasi (Rg. No: 2207012987) Dr. Manik Sonawane Principal, (SDA) Head, Dept.of Political science, Mumbai Central. T.M.V. Sadashiv Peth, Pune DEPARTMENT OF POLITICAL SCIENCE TILAK MAHARASHTRA UNIVERSITY SADASHIV PETH, PUNE 411031 JANUARY 2013 DECLARATION BY THE CANDIDATE I, Robinson Undrasi declare on oath that the references and literature which are quoted in my dissertation entitle “Regional imbalance in the Indian state of Andhra Pradesh with special reference to Telangana” are from original sources and are acknowledged at the appropriate place in the dissertation. I declare further that I have not used this information for any purpose other than my research. Place : Mumbai Date : January, 2013 (Robinson Undrasi) Dr. Manik D. Sonawane Post-Graduate Dept. of Political M.A., M.Phil, Ph.d. Science and Public Administration, Head of the Department Tilak Maharashtra Vidya Peeth Sadashiv Peth, Pune. 411030 Ph. 020-24454866 ==================================================== CERTIFICATE BY GUIDE This is Certified that the work incorporated in his ‘M.Phil’ dissertation “Regional imbalance in the Indian state of Andhra Pradesh with special reference to Telangana” submitted by Robinson Undrasi was carried out under my supervision. Such material as obtained from other sources has been duly acknowledged in the dissertation. Date: / / Dr. Manik D. Sonawane ACKNOWLEDGEMENT I express my sincere gratitude to my guide Dr. Manik Sonawane, Head of Department of Political Science Tilak Maharashtra Vidyapeth for his valuable guidance, critical comments, encourage and constent inspiration throughout this course of investigation. -

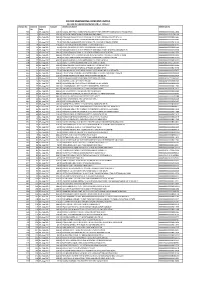

Elecon Engineering Company Limited Details of Unpaid Dividend for F.Y

ELECON ENGINEERING COMPANY LIMITED DETAILS OF UNPAID DIVIDEND FOR F.Y. 2016-17 Cheque No Warrant Warrant Amount Beneficiary Name Reference No No Date 580 1 05-Aug-2017 120.00 KAWAL JEET GILL C O BRIG SPS GILL DEPUTY GEN OFFICER COMMANDING HQ 24 INFAN 0000000000000K011604 581 2 05-Aug-2017 150.00 JAI SINGH RAWAT 4488 PUNJAB AND SIND BANK 00001201910101709134 585 6 05-Aug-2017 480.00 KAMLESH JAGGI C O SHRI T N JAGGI B 471 NEW FRIENDS COLONY MATHU 0000000000000K011985 588 9 05-Aug-2017 120.00 SATYAKAM C O RITES 27 BARAKHAMBA ROAD ROOM NO 605 NEW DELHI HOUSE 0000000000000S013492 590 11 05-Aug-2017 75.00 PRANOB CHAKRABORTY EMTICI ENG LTD 418 WORLD TRADE CENTRE 0000000000000P010194 593 14 05-Aug-2017 120.00 VEENA AHUJA 18 KHAN MARKET FLATS NEW DELHI 0000000000000V010147 594 15 05-Aug-2017 25.00 RAMA CHANDRA ACHARYA 233 JOR BAGH NEW DELHI 0000000000000R001546 595 16 05-Aug-2017 120.00 SANSAR CHAND SUD 1815 SECOND FLOOR UDAI CHAND M KOTLA MUBARAKPUR 0000000000000S013338 598 19 05-Aug-2017 160.00 PARSHOTAM LAL BAJAJ 1C 29 NEW ROHTAK ROAD NEW DELHI 0000000000000P011250 603 24 05-Aug-2017 480.00 VAIKUNTH NATH SHARMA 2 1786 NEAR BHAGIRATH PALACE CHANDNI CHOWK 0000000000000V011321 605 26 05-Aug-2017 80.00 MUKESH KAPOOR 506 KRISHNA GALI KATRA NEEL CHANDNI CHOWK 0000000000000M012161 606 27 05-Aug-2017 600.00 MOHD ASHEQIN C O GULAB TRADING CO 5585 S B DELHI 0000000000000M012009 608 29 05-Aug-2017 62.50 SHASHI CHOPRA 01190005348 STATE BANK OF INDIA 0000IN30039415130730 609 30 05-Aug-2017 120.00 USHA MATHUR 144 PRINCESS PARK PLOT NO 33 SECTOR 6 0000000000000U010436 -

24Th Session of the All-India Trade Union Congress, Calcutta, May 27

§ ★ Report & Resolutions ★ (AldlTl. MAI 3^-29, 1954 CONTENTS APPEAL TO ALL WORKERS AND TRADE UNIONS FOR UNITY REVIEW OF THE 24TH SE;^ION — by S. A. Dange 5 PREPARATIONS AND PROCEEDINGS PRESIDENTIAL SPEECH OF V. CHAKKARAI CHETTIAR 29 GREETINGS TO THE SESSION 36 REPORT OF THE GENERAL SECRETARY 43 I. Vigilance against Warmongers 43 II. Economic Condition 46 III. The Struggles 51 IV. Fight for Living Wage 62 V. Labour Laws — Some Gains and Losses 65 VI. Trade-Union Rights and Democratic Liberties 69 VII. Trade Union Unity 73 VIII. International Solidarity — WFTU 77 Conclusion 79 REPORT ON ORGANISATION OF THE AITUC 81 , I Centre 85 State TUCs 87 International Solidarity — WFTU 88 RESOLUTIONS 90 On Martyrs SO Condolence Resolutions so On Affiliations 91 On WFTU 91 Greetings to the AUCCTU Congress Thanks for Hospital Aid 'On Unemployment On Rationalisation and Speed-up On Peace 100 On Trade-Union Rights and Democratic Liberties 103 On Industrial Relations 106 On Social Security 108 On Discrimination in Granting Passports 113 On French and Portuguese Possessions in India 114 On Contract Labour 115 On Industrial Housing 115 On Railwaymen’s Demands 118 On Cotton Textile Industry and Its Workers 123 On Jute Industry and Workers 127 On Plantation Industry 131 On Handloom Industry 134 ■On Coal Miners’ Demands 136 On Manganese 137 On Petroleum Workers 137 On Silk Industry Workers 138 On Railway Collieries 139 On Calcutta Tramway Workers 142 On Motor Transport Workers 142 On Bank Employees’ Movement 146 On Insurance Employees 148 On Working Women 150 -

Anthems of Resistance

A Celebration of Progressive Urdu Poetry Anthems of Resistance So what if my pen has been snatched away from me I hav dipped my fingers in the blood of my heart So what if my mouth has been sealed, I have turned Every link of my chain in to a speaking tonge Ali Husain Mir & Raza Mir 1 Anthems of Resistance A Celebration of Progressive Urdu Poetry Ali Husain Mir & Raza Mir IndiaInk 2 Brahma’s Dream ROLI BOOKS © Ali Husain Mir and Raza Mir, 2006 First published in 2006 IndiaInk An imprint of Roli Books Pvt. Ltd. M-75, G.K. II Market New Delhi 110 048 Phones: ++91 (011) 2921 2271, 2921 2782 2921 0886, Fax: ++91 (011) 2921 7185 E-mail: [email protected]; Website: rolibooks.com Also at Varanasi, Bangalore, Jaipur Cover : Arati Subramanyam Layout : Narendra Shahi ISBN: 81-86939-26-1 Rs. 295 Typeset in CentSchbook BT by Roli Books Pvt. Ltd. and printed at Syndicate Binders, New Delhi 3 CONTENTS Acknowledgements A Note on Translation and Transliteration Preface 1 Over Chinese Food: The Progressive Writers’ Association 2 Urdu Poetry and the Progressive Aesthetic 3 Saare Jahaan Se Achcha: Progressive Poets and the Problematic of Nationalism 4 From Home to the World: The Internationalist Ethos 5 Dream and Nightmare: The Flirtation with Modernity 6 Progressive Poetry and Film Lyrics 7 Voh Yaar Hai Jo Khushboo Ki Taraah, Jis Ki Zubaañ Urdu Ki Taraah 8 An Exemplary Progressive: The Aesthetic Experiment of Sahir Ludhianvi 9 Javed Akhtar’s Quiver of Progressive Arrows: A Legacy Survives 10 New Standard Bearers of Progressive Urdu Poetry: The Feminist Poets 11 A Requiem .. -

The Bahmanis of Gulbarga

A Study of Communal Conflict and Peace Initiatives in Hyderabad: Past and Present Conducted By COVA Research Team: M.A. Moid Shashi Kumar B. Pradeep Anita Malpani K. Lalita Supervision Mazher Hussain In Collaboration with Aman Trust, New Delhi 2005 Part I Communal Conflict and Peace Initiatives in Hyderabad Deccan: The Historical Context Research: M.A. Moid In the last decade or so, communalism has come be a major issue of concern when examining the Indian social fabric. Many efforts have been made to understand the various nuances of the problem. While the roots of present-day communal conflicts and riots could be traced to socio-economic and political causes, communalism has its roots in history. Colonialist policies, modernization, mass politics, competition, identity and culture are the different facets of this debate. In Hyderabad, Hindu-Muslim relations have a long history, spread over four centuries. The immediate history of the last five decades is particularly significant to understand the issue of communalism in Hyderabad. In the following pages, an attempt has been made to trace the roots of the communal conflict in Hyderabad. Some basic questions sought to be answered are: How did the Muslims arrive in Deccan? How was their settling down in the South different from their engagements in North India? How did the Hindus react to the new arrivals? How did the Muslims become a part of the Deccan and how did a composite culture develop? The study is divided into five parts. Part I is about the first Muslim kingdom of the South, covering Allauddin Khilji’s arrival and Mohammed Bin Tughlaq's involvement in the Deccan, up to the establishment of the Bahmani Kingdom and its achievements. -

ISSN 2250 – 1959(0Nline) 2348 – 9367 (Print) an Internationally Indexed Peer Reviewed & Refereed Journal

International Research Journal of Management Science & Technology ISSN 2250 – 1959(0nline) 2348 – 9367 (Print) An Internationally Indexed Peer Reviewed & Refereed Journal Shri Param Hans Education & Research Foundation Trust www.IRJMST.com www.SPHERT.org Published by iSaRa Solutions IRJMST Vol 8 Issue 1 [Year 2017] ISSN 2250 – 1959 (0nline) 2348 – 9367 (Print) CULTURAL EFFLORESENCE CONTRIBUTION OF NAWAB MIR OSMAN ALI KHAN FROM 1911-1948. IN THE MIRROR OF ARCHIVES. Author by : DR.JAYARAM GOLLAPUDI, M.A.,M.Phil., Ph.D., All the records preserved in Andhra Pradesh State Archives and Research Institute serve as extremely valuable primary source material and as rich documentary evidences, holding for retrospective research. Who are working on every aspects of life of the reign of Asaf Jahi’s., political, economic administrative and social history of the Deccan. Andhra Pradesh State Archives and Research Institute possesses in its custody 50 millions of old and historical records not only for recent administrative records but also the records of the various dynasties of the Deccan such as the Bahmani, ‘Qutubshahi”, ‘Adilshahi” and “Mughals” as well as a large quantum of a perfect series of Asaf Jahi records apart from these Andhra State, Andhra Pradesh, and Madras Presidency records also in Persian, Urdu, Marathi, Telugu and English language are available. An attempt is made to highlight the “Cultural Contribution of Nawab Mir Osman Ali Khan 1911-1948”. This Article provides a salient features on the contribution of ‘Nizam VII” in chronological order the achievements based on the original Persian and Urdu source material of Archives. In the annals of the Hyderabad history, the role of ‘Nawab Mir Osman Ali Khan” was promoted cultural, administrative and economic development of Hyderabad was impanel.