Urdu in Hyderabad State*

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Authority, Knowledge and Practice in Unani Tibb in India, C. 1890

Authority, Knowledge and Practice in UnaniTibb in India, c. 1890 -1930 Guy Nicolas Anthony Attewell Dissertation submitted in partial fulfilment for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, School of Oriental and African Studies, University of London ProQuest Number: 10673235 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a com plete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. uest ProQuest 10673235 Published by ProQuest LLC(2017). Copyright of the Dissertation is held by the Author. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States C ode Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. ProQuest LLC. 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106- 1346 Abstract This thesis breaks away from the prevailing notion of unanitibb as a ‘system’ of medicine by drawing attention to some key arenas in which unani practice was reinvented in the early twentieth century. Specialist and non-specialist media have projected unani tibb as a seamless continuation of Galenic and later West Asian ‘Islamic’ elaborations. In this thesis unani Jibb in early twentieth-century India is understood as a loosely conjoined set of healing practices which all drew, to various extents, on the understanding of the body as a site for the interplay of elemental forces, processes and fluids (humours). The thesis shows that in early twentieth-century unani ///)/; the boundaries between humoral, moral, religious and biomedical ideas were porous, fracturing the realities of unani practice beyond interpretations of suffering derived from a solely humoral perspective. -

Anchoring Heritage with History—Minto Hall

Oprint from & PER is published annually as a single volume. Copyright © 2014 Preservation Education & Research. All rights reserved. Articles, essays, reports and reviews appearing in this journal may not be reproduced, in whole or in part, except for classroom and noncommercial use, including illustrations, in any form (beyond copying permitted by sections 107 and 108 of the U.S. Copyright Law), without written permission. ISSN 1946-5904 PRESERVATION EDUCATION & RESEARCH Preservation Education & Research (PER) disseminates international peer-reviewed scholarship relevant to historic environment education from fields such as historic EDITORS preservation, heritage conservation, heritage studies, building Jeremy C. Wells, Roger Williams University and landscape conservation, urban conservation, and cultural ([email protected]) patrimony. The National Council for Preservation Education (NCPE) launched PER in 2007 as part of its mission to Rebecca J. Sheppard, University of Delaware exchange and disseminate information and ideas concerning ([email protected]) historic environment education, current developments and innovations in conservation, and the improvement of historic environment education programs and endeavors in the United BOOK REVIEW EDITOR States and abroad. Gregory Donofrio, University of Minnesota Editorial correspondence, including manuscripts for ([email protected]) submission, should be emailed to Jeremy Wells at jwells@rwu. edu and Rebecca Sheppard at [email protected]. Electronic submissions are encouraged, but physical materials can be ADVISORY EDITORIAL BOARD mailed to Jeremy Wells, SAAHP, Roger Williams University, One Old Ferry Road, Bristol, RI 02809, USA. Articles Steven Hoffman, Southeast Missouri State University should be in the range of 4,500 to 6,000 words and not be Carter L. Hudgins, Clemson University/College of Charleston under consideration for publication or previously published elsewhere. -

Rewa State Census, Volume-1

1931 Volume I REPORT BY PANDIT PHAWANI DATT' JOSHI, B. A Advocate Genpra t1 ·",a State, (SAGHELKH I-l N D) C. I. I n-charge Compilation of Census Report. 1934. 1;'RINTED AT THE STANDAt..) PRESS, ALLAHABAD- TABLE OF CONTENTS PART I.-REPORT. P.AGE. Introduction 1 Chapter I. Distribution and Movement of the Population 1-14 II. Population of City, Towns and Villages " 15-~2 ., III. Birth'place and Migration i'3-!J0 IV. Age 31-42 V. Sex 43-49 VI. Civil Condition 50-61 VII. Infirmities 62-68 VIII. Occupation 09-91 IX. Literacy 92-](10 " X. Language 101-109 XI. Religion 110-112 1 XII. Caste " ]]3-118 LIST OF MAPS & DIAGRAMS. 1. l\Iap of the State FRONTISPIECE. 1 2. Diagram showing the growth of the population of Bhopal State 188.1-1931 12 3. Diagram showing the density of population in Bhopal State and in ot her districts and States. 13 4. Diagram showing the increase or decrease per cent in the population of the ~izamats and the Tahsils of Bhopal State during the inter-censal period 1921-1931. 14 o. Diagram showing percentage variation in urban and rural population 21 6. The urban popUlation per 1,000 22 1. The rural population per 1,OUO 22 I:l. Diagram showing the distribution by quinquennial age-periods of 10,000 of each sex, Bhopal State, 1931. 4 I 9. Age distribution of 10,000 of each sel( in Bhopal State 42 10. Diagrams showing the numbers of females per 1,000 males by main age-periods, 1931.. -

The Pathetic Condition of Hussain Sagar Lake Increasing of Water Pollution After Immersion of Ganesh-Idols in the Year-2016, Hyderabad, Telangana, India

International Journal of Research in Engineering and Applied Sciences (IJREAS) Available online at http://euroasiapub.org/journals.php Vol. 6 Issue 10, October - 2016, pp. 136~143 ISSN(O): 2249-3905, ISSN(P) : 2349-6525 | Impact Factor: 6.573 | Thomson Reuters ID: L-5236-2015 THE PATHETIC CONDITION OF HUSSAIN SAGAR LAKE INCREASING OF WATER POLLUTION AFTER IMMERSION OF GANESH-IDOLS IN THE YEAR-2016, HYDERABAD, TELANGANA, INDIA Bob Pears1 Head of General Section .J.N. Govt. Polytechnic ,Hyderabad, Telangana, India. Prof. M. Chandra Sekhar2 . Registrar, NIT, Warangal, Telangana,India. Abstract: During the past few years grave concern is being voiced by people from different walks of life over the deteriorating conditions of Hussain Sagar Lake. As a result of heavy anthropogenic pressures, the eco-systems of lake are not only strengthening in its surface becoming poor in quality, posing health hazards to the people living in around close proximity to the lake. Over the years the entire eco-system of Hussain Sagar Lake has changed. The water quality has deteriorated considerably during the last three decades. Over the years the lake has become pollution due to immersion of Ganesh Idols. Many undesirable changes in the structure of biological communities have resulted and some important species have either declined or completely disappeared. Keywords: Groundwater quality, PH , Turbidity,TDS, COD, BOD, DO, before immersing of idols, after immersing of idols. INTRODUCTION Hyderabad is the capital city of Telangana and the fifth largest city in India with a population of 4.07 million in 2010 is located in the Central Part of the Deccan Plateau. -

03404349.Pdf

UA MIGRATION AND DEVELOPMENT STUDY GROUP Jagdish M. Bhagwati Nazli Choucri Wayne A. Cornelius John R. Harris Michael J. Piore Rosemarie S. Rogers Myron Weiner a ........ .................. ..... .......... C/77-5 INTERNAL MIGRATION POLICIES IN AN INDIAN STATE: A CASE STUDY OF THE MULKI RULES IN HYDERABAD AND ANDHRA K.V. Narayana Rao Migration and Development Study Group Center for International Studies Massachusetts Institute of Technology Cambridge, Massachusetts 02139 August 1977 Preface by Myron Weiner This study by Dr. K.V. Narayana Rao, a political scientist and Deputy Director of the National Institute of Community Development in Hyderabad who has specialized in the study of Andhra Pradesh politics, examines one of the earliest and most enduring attempts by a state government in India to influence the patterns of internal migration. The policy of intervention began in 1868 when the traditional ruler of Hyderabad State initiated steps to ensure that local people (or as they are called in Urdu, mulkis) would be given preferences in employment in the administrative services, a policy that continues, in a more complex form, to the present day. A high rate of population growth for the past two decades, a rapid expansion in education, and a low rate of industrial growth have combined to create a major problem of scarce employment opportunities in Andhra Pradesh as in most of India and, indeed, in many countries in the third world. It is not surprising therefore that there should be political pressures for controlling the labor market by those social classes in the urban areas that are best equipped to exercise political power. -

REPORT of the Indian States Enquiry Committee (Financial) "1932'

EAST INDIA (CONSTITUTIONAL REFORMS) REPORT of the Indian States Enquiry Committee (Financial) "1932' Presented by the Secretary of State for India to Parliament by Command of His Majesty July, 1932 LONDON PRINTED AND PUBLISHED BY HIS MAJESTY’S STATIONERY OFFICE To be purchased directly from H^M. STATIONERY OFFICE at the following addresses Adastral House, Kingsway, London, W.C.2; 120, George Street, Edinburgh York Street, Manchester; i, St. Andrew’s Crescent, Cardiff 15, Donegall Square West, Belfast or through any Bookseller 1932 Price od. Net Cmd. 4103 A House of Commons Parliamentary Papers Online. Copyright (c) 2006 ProQuest Information and Learning Company. All rights reserved. The total cost of the Indian States Enquiry Committee (Financial) 4 is estimated to be a,bout £10,605. The cost of printing and publishing this Report is estimated by H.M. Stationery Ofdce at £310^ House of Commons Parliamentary Papers Online. Copyright (c) 2006 ProQuest Information and Learning Company. All rights reserved. TABLE OF CONTENTS. Page,. Paras. of Members .. viii Xietter to Frim& Mmister 1-2 Chapter I.—^Introduction 3-7 1-13 Field of Enquiry .. ,. 3 1-2 States visited, or with whom discussions were held .. 3-4 3-4 Memoranda received from States.. .. .. .. 4 5-6 Method of work adopted by Conunittee .. .. 5 7-9 Official publications utilised .. .. .. .. 5. 10 Questions raised outside Terms of Reference .. .. 6 11 Division of subject-matter of Report .., ,.. .. ^7 12 Statistic^information 7 13 Chapter n.—^Historical. Survey 8-15 14-32 The d3masties of India .. .. .. .. .. 8-9 14-20 Decay of the Moghul Empire and rise of the Mahrattas. -

Are You Suprised ?

CURRICULUM VITAE Dr. A. PATRICK, Asst Professor, Department of Commerce, University College of Commerce & Business Management Osmania University, Hyderabad -7 Residence Address: 2-15-30/1A, Prashant Nagar, Berrappagadda Uppal, Hyderabad -7 Cell No.: 9247799257 Residence: 040-27200584 E-mail: [email protected] CAREER OBJECTIVE: “To carve a niche for myself in the field of Commerce and Management, by learning and imparting to the academic and industrial excellence.” EDUCATIONAL CREDENTIALS: 1. Doctor of Philosophy (Ph. D), with topic titled “CUSTOMER RELATIONSHIP MANAGEMENT - A DYADIC EXPLORATION IN SELECT BANKS”, from Department of Commerce, Osmania University, Hyderabad, Andhra Pradesh, August, 2005 2. Master of Business Administration (MBA) from Indira Gandhi Open University (IGNOU), New Delhi, June 2003, with specialization in Financial Management, with an overall Point Grade of 4, on a 5 point scale. 3. Master of Commerce (M.Com) passed with Distinction from Osmania University, May 1997. 4. Bachelor of Commerce passed in First Division form Osmania University, March 1995. 5. Qualified in State Level Eligibility Test for Lectureship (SLET), Commerce, July 1997conducted by APCSC (Andhra Pradesh College Service Commission) accredited by UGC. 6. Qualified in National Eligibility Test (NET), Management, December 2012 Conducted by UGC 7. Computer awareness: MS Windows 7, XP, MS – Office. Page 1 of 18 WORK EXPERIENCE: FOREIGN EXPERIENCE: 1. Worked as Lecturer in Management, in the Department of Management, Faculty of Business & Economics, Arba Minch University, Ethiopia, North East Africa P.O. Box: 21, from October 2003 to July 2005. Job Description: The job involved teaching assignment to university students in the areas of Basic Marketing, Quantitatives for Business Decisions, Marketing Research, Organizational Behavior and evaluating projects in the areas of Marketing and Social issues in Ethiopia. -

H.E.H. the Nizam.S Dominions, Administration Report, Part III, Vol

Census of India, 1931 VOLUME XXIU H.E.H. the NiZalll's Dominions .(HYDERABAD STATE) PART III-Administration Report BY GULAM AHMED KHAN Census Commissioner HYDERABAD-DEtCAN. AT THE GOVERNMENT CENTRAL PRESS 1934 ,...... ~ OJ. 0- ._C H ~ r- r.f) -._, ~ U- rJ) 0.. • .-1 Z ~ ~ r..n U .. I CHAPTER I. The Administrative Report on Census sets forth the course run, the difficulties encountered and overcome and suggestions for the guidance of the next Census Commissioner. It is an important reference book and the absence of it not only means incomplej;eness of census work but also entails considerable hardship to the next officei~. Although five Census Commissioners have preceded me~ no one except that for 1901 has left a record of bis ex periences. In his introductory chapter of the Report volume (Part I) for 1921:J the then Census Commissioner observed that in the absence of the Administrative volume of the previous census it was found necessary for him to wade through a number of old files with a view to arriving at a de finite plan of work and hoped that" the Administrative volume to be published this time will give a detailed account of the machinery by which the Census work was managed and the methods of enumeration and tabula tion followed at the present Census. n But when I took over the duties of the Census Comrnissioner I had no alternative but to collect and study the files and follow the remarks left by my predecessor. 2. As suggested by the Census Commissioner for India.I have collected Collection of Printed Matter a few copies of all printed matter and- have them bound in the following order :- 1. -

THE COAT of ARMS an Heraldic Journal Published Twice Yearly by the Heraldry Society the COAT of ARMS the Journal of the Heraldry Society

Third Series Vol. II part 2. ISSN 0010-003X No. 212 Price £12.00 Autumn 2006 THE COAT OF ARMS an heraldic journal published twice yearly by The Heraldry Society THE COAT OF ARMS The journal of the Heraldry Society Third series Volume II 2006 Part 2 Number 212 in the original series started in 1952 The Coat of Arms is published twice a year by The Heraldry Society, whose registered office is 53 High Street, Burnham, Slough SL1 7JX. The Society was registered in England in 1956 as registered charity no. 241456. Founding Editor † John Brooke-Little, C.V.O., M.A., F.H.S. Honorary Editors C. E. A. Cheesman, M.A., PH.D., Rouge Dragon Pursuivant M. P. D. O'Donoghue, M.A., Bluemantle Pursuivant Editorial Committee Adrian Ailes, B.A., F.S.A., F.H.S. Jackson W. Armstrong, B.A. Andrew Hanham, B.A., PH.D Advertizing Manager John Tunesi of Liongam PLATE 4 Osmond Barnes, Chief Herald at the Imperial Assemblage at Delhi, 1876-7 Private Collection. See page 108. HERALDS AT THE DELHI DURBARS Peter O 'Donoghue Three great imperial durbars took place on the Ridge outside Delhi during the height of the British Raj, on a site which was associated with the heroics of the Mutiny. The first durbar, in 1876-77, proclaimed Queen Victoria as Empress of India, whilst the second and third, in 1902-3 and 1911, proclaimed the accessions of Edward VII and George V respectively. All three drew upon Indian traditions of ceremonial meetings or durbars between rulers and ruled, and in particular upon the Mughal Empire's manner of expressing its power to its subject princes. -

The Book Only

TEXT CROSS WITHIN THE BOOK ONLY ~n<00 OU 158086 >m Hyderabad State List of Leading Officials, Nobles and Personages HYDERABAD RESIDENCY GOVERNMENT PRESS 1987. List of A ia from whom Government of India Publications are available, Provincial Government Book Depots. , Government Press, Mount Road, Madras. BonnAY j Superintendent, Government Printing and Stationery, Queens Eoad, Bombay. BIND i- Manager, Bind Govt. Book Depot and Record Office, Karachi (Sadarj. UNITED FBOTIHCBS {Superintendent, Government Press, Allahabad. PusJAB: Superintendent, Government Printing, Punjab, Lahore. BCBMA Superintendent, Government Printing, Burma, Ban goon. CBNTBAL PBOVINCKB : Superiatendent, Gorerninent Printing, Central Provinces, Nagpur. ABAM Superintendent, As*am Secretariat Press, Shillong. BIHAB : Superintendent, Government Printing, P. 0. Gulzarbagb, Patna. NOBTH-WKST FKDNTIER PBaviNCfi; -Manager, Government Printing and Stationery, Peshawar. OBMSA:-Press Officer, Secretariat, Cuttack. (b) Private Booksellers. Advanl Bros., P. 0. Box 100, Cawnpore. Malhotra & Co., Post Box No. 01, Lahore. Messrs. U. P. Aero Stores. Karachi.* Mluutva Book Shop, Anarkali Street, Lahore. BantMya & Co.. Ltd., Station Goad, Ajmer. Modern Bjok Depot, Baiar Road,8lalkot Cantonment. Bengal Flying Club, Dnm Dum Cantonment.* Modern Book Depot, Napier Road, Jnllnndur Cantonment. Bbawnanl & Sons. New Delhi. Mohanlal Dossabhai Bhah. Rajkot. Book Company, Calcutta. Nandkishore & Bros., Chowk, Beaares City. New Booklover's Resort, Taikad, Trivnndram, South India. Book Co., "Kitab Mahal "198, Hornby Road, Bom- bay. Burma Hook Club, Ltd., Rangoon. Newman & Co., Ltd., Calcutta, Messrs. W. Batterworth & Co., (India), Ltd.. Calcutta. Oxford Book and Stationery Company, Delhi, Laboie. Careers : Mohini Lahore. Road, bimla, Meernl and Calcutta. & Baoharam Calcutta. Cbatterjee Co., 3. Chatterjee Lane, Parikh & Co., Baroda, Messrs. B. Choke; vertty. Chatterjee & Co., Ltd , 13, College Square. -

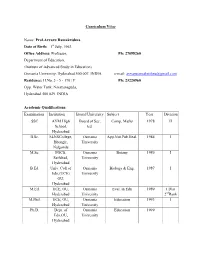

Curriculum Vitae Name: Prof.Avvaru Ramakrishna Date of Birth

Curriculum Vitae Name: Prof.Avvaru Ramakrishna Date of Birth: 1st July, 1963. Office Address: Professor, Ph: 27098260 Department of Education, (Institute of Advanced Study in Education) Osmania University, Hyderabad 500 007. INDIA e-mail: [email protected] Residence: H.No. 3 - 5 - 170 / F Ph: 23220960 Opp. Water Tank, Narayanaguda, Hyderabad 500 029. INDIA Academic Qualifications: Examination Institution Board/University Subject Year Division SSC AYM High Board of Sec. Comp, Maths 1978 II School, Ed. Hyderabad B.Sc. SLNSCollege, Osmania App.Nut.Pub.Heal. 1984 I Bhongir, University Nalgonda M.Sc. PGCS, Osmania Botany 1986 I Saifabad, University Hyderabad B.Ed. Univ. Coll of Osmania Biology & Eng. 1987 I Edn,(UCE) University OU, Hyderabad M.Ed. UCE, OU, Osmania Eval. in Edn 1989 I Dist Hyderabad University 2ndRank M.Phil. UCE, OU, Osmania Education 1993 I Hyderabad University Ph.D. Dept. of Osmania Education 1999 Edn.OU, University Hyderabad Administrative Responsibilities held: Chairperson, Board of Studies in Special Education during March 2007 to June 2009 Chairperson, Board of Studies in Education during June 2009 to November 2011 Head, Department of Education Principal, College of Education, IASE, O.U during June 1st 2016 to till date. Research Experience: 1. Prepared a Dissertation on "Construction of a Scale for assessing the Essential Characteristics of Secondary School Teachers" as a Partial fulfilment for the award of M.Phil Degree in Education, Osmania University, Hyderabad. 2. Prepared a Thesis titled "Curriculum for Disaster Preparedness" for the award of Doctor of Philosophy in Education, Osmania University, Hyderabad. Teaching Experience: Name of the institution Courses taught Duration Sri Vivekananda Residential Primary Sections 5-2-1989 to 10-4-1989 School,Karimnagar Ekashila College of Education B.Ed 21-1-1990 to 10-8-1990 Janagoan, Warangal, A.P. -

The Urban Morphology of Hyderabad, India: a Historical Geographic Analysis

Western Michigan University ScholarWorks at WMU Master's Theses Graduate College 6-2020 The Urban Morphology of Hyderabad, India: A Historical Geographic Analysis Kevin B. Haynes Western Michigan University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wmich.edu/masters_theses Part of the Human Geography Commons, and the Remote Sensing Commons Recommended Citation Haynes, Kevin B., "The Urban Morphology of Hyderabad, India: A Historical Geographic Analysis" (2020). Master's Theses. 5155. https://scholarworks.wmich.edu/masters_theses/5155 This Masters Thesis-Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate College at ScholarWorks at WMU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Master's Theses by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at WMU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE URBAN MORPHOLOGY OF HYDERABAD, INDIA: A HISTORICAL GEOGRAPHIC ANALYSIS by Kevin B. Haynes A thesis submitted to the Graduate College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science Geography Western Michigan University June 2020 Thesis Committee: Adam J. Mathews, Ph.D., Chair Charles Emerson, Ph.D. Gregory Veeck, Ph.D. Nathan Tabor, Ph.D. Copyright by Kevin B. Haynes 2020 THE URBAN MORPHOLOGY OF HYDERABAD, INDIA: A HISTORICAL GEOGRAPHIC ANALYSIS Kevin B. Haynes, M.S. Western Michigan University, 2020 Hyderabad, India has undergone tremendous change over the last three centuries. The study seeks to understand how and why Hyderabad transitioned from a north-south urban morphological directional pattern to east-west during from 1687 to 2019. Satellite-based remote sensing will be used to measure the extent and land classifications of the city throughout the twentieth and twenty-first century using a geographic information science and historical- geographic approach.