Anchoring Heritage with History—Minto Hall

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

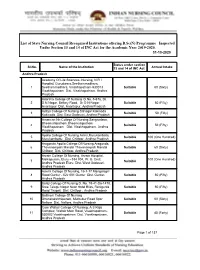

Programme Inspected Under Section 13 and 14 of INC Act for the Academic Year 2019-2020

List of State Nursing Council Recognised Institutions offering B.Sc(N) Programme Inspected Under Section 13 and 14 of INC Act for the Academic Year 2019-2020. 31-10-2020 Status under section Sl.No. Name of the Institution 13 and 14 of INC Act Annual Intake Andhra Pradesh Academy Of Life Sciences- Nursing, N R I Hospital, Gurudwara,Seethammadhara, 1 Seethammadhara, Visakhapatnam-530013 Suitable 60 (Sixty) Visakhapatnam Dist. Visakhapatnam, Andhra Pradesh Adarsha College Of Nursing D.No. 5-67a, Dr. 2 D.N.Nagar, Bellary Road, Dr D N Nagar Suitable 50 (Fifty) Anantapur Dist. Anantapur, Andhra Pradesh Aditya College Of Nursing Srinagar Kakinada 3 Suitable 50 (Fifty) Kakinada Dist. East Godavari, Andhra Pradesh American Nri College Of Nursing Sangivalasa, Bheemunipatnam Bheemunipatnam 4 Suitable 50 (Fifty) Visakhapatnam Dist. Visakhapatnam, Andhra Pradesh Apollo College Of Nursing Aimsr,Murukambattu 5 Suitable 100 (One Hundred) Murukambattu Dist. Chittoor, Andhra Pradesh Aragonda Apollo College Of Nursing Aragonda, 6 Thavanampalli Mandal Thavanampalli Mandal Suitable 60 (Sixty) Chittoor Dist. Chittoor, Andhra Pradesh Asram College Of Nursing, Asram Hospital, Malkapuram, Eluru - 534 004, W. G. Distt. 100 (One Hundred) 7 Suitable Andhra Pradesh Eluru Dist. West Godavari, Andhra Pradesh Aswini College Of Nursing, 15-1-17 Mangalagiri 8 Road Guntur - 522 001 Guntur Dist. Guntur, Suitable 50 (Fifty) Andhra Pradesh Balaji College Of Nursing D. No. 19-41-S6-1478, 9 Sree Telugu Nagar Near Hotel Bliss, Renigunta Suitable 50 (Fifty) Road Tirupati Dist. Chittoor , Andhra Pradesh Bollineni College Of Nursing 10 Dhanalakshmipuram, Muthukur Road Spsr Suitable 60 (Sixty) Nellore Dist. Nellore, Andhra Pradesh Care Waltair College Of Nursing, A S Raja Complex, Waltair Main Road, Visakhapatnam- 11 Suitable 40 (Forty) 530002 Visakhapatnam Dist. -

PIN Code Name of the City 380001 AHMEDABAD 380002 AHMEDABAD 380003 AHMEDABAD 380004 AHMEDABAD 380005 AHMEDABAD 380006 AHMEDABAD

PIN codes mapped to T30 cities as on 31-Mar-2021 PIN Code Name of the City 380001 AHMEDABAD 380002 AHMEDABAD 380003 AHMEDABAD 380004 AHMEDABAD 380005 AHMEDABAD 380006 AHMEDABAD 380007 AHMEDABAD 380008 AHMEDABAD 380009 AHMEDABAD 380013 AHMEDABAD 380014 AHMEDABAD 380015 AHMEDABAD 380016 AHMEDABAD 380018 AHMEDABAD 380019 AHMEDABAD 380021 AHMEDABAD 380022 AHMEDABAD 380023 AHMEDABAD 380024 AHMEDABAD 380025 AHMEDABAD 380026 AHMEDABAD 380027 AHMEDABAD 380028 AHMEDABAD 380049 AHMEDABAD 380050 AHMEDABAD 380051 AHMEDABAD 380052 AHMEDABAD 380054 AHMEDABAD 380055 AHMEDABAD 380058 AHMEDABAD 380059 AHMEDABAD 380060 AHMEDABAD 380061 AHMEDABAD 380063 AHMEDABAD 382210 AHMEDABAD 382330 AHMEDABAD 382340 AHMEDABAD 382345 AHMEDABAD 382350 AHMEDABAD 382405 AHMEDABAD 382415 AHMEDABAD 382424 AHMEDABAD 382440 AHMEDABAD 382443 AHMEDABAD 382445 AHMEDABAD 382449 AHMEDABAD 382470 AHMEDABAD 382475 AHMEDABAD 382480 AHMEDABAD 382481 AHMEDABAD 560001 BENGALURU 560002 BENGALURU 560003 BENGALURU 560004 BENGALURU 560005 BENGALURU 560006 BENGALURU 560007 BENGALURU 560008 BENGALURU 560009 BENGALURU 560010 BENGALURU PIN codes mapped to T30 cities as on 31-Mar-2021 PIN Code Name of the City 560011 BENGALURU 560012 BENGALURU 560013 BENGALURU 560014 BENGALURU 560015 BENGALURU 560016 BENGALURU 560017 BENGALURU 560018 BENGALURU 560019 BENGALURU 560020 BENGALURU 560021 BENGALURU 560022 BENGALURU 560023 BENGALURU 560024 BENGALURU 560025 BENGALURU 560026 BENGALURU 560027 BENGALURU 560029 BENGALURU 560030 BENGALURU 560032 BENGALURU 560033 BENGALURU 560034 BENGALURU 560036 BENGALURU -

Sara Aghamohammadi, M.D

Sara Aghamohammadi, M.D. Philosophy of Care It is a privilege to care for children and their families during the time of their critical illness. I strive to incorporate the science and art of medicine in my everyday practice such that each child and family receives the best medical care in a supportive and respectful environment. Having grown up in the San Joaquin Valley, I am honored to join UC Davis Children's Hospital's team and contribute to the well-being of our community's children. Clinical Interests Dr. Aghamohammadi has always had a passion for education, she enjoys teaching principles of medicine, pediatrics, and critical care to medical students, residents, and nurses alike. Her clinical interests include standardization of practice in the PICU through the use of protocols. Her team has successfully implemented a sedation and analgesia protocol in the PICU, and she helped develop the high-flow nasal cannula protocol for bronchiolitis. Additionally, she has been involved in the development of pediatric pain order sets and is part of a multi-disciplinary team to address acute and chronic pain in pediatric patients. Research/Academic Interests Dr. Aghamohammadi has been passionate about Physician Health and Well-being and heads the Wellness Committee for the Department of Pediatrics. Additionally, she is a part of the Department Wellness Champions for the UC Davis Health System and has given presentations on the importance of Physician Wellness. After completing training in Physician Health and Well-being, she now serves as a mentor for the Train-the-Trainer Physician Health and Well-being Fellowship. -

SCS-CN Method for Surface Runoff Calculation of Agricultural Watershed Area of Bhojtal Priyanka Dwivedi1, Abhishek Mishra2, Sateesh Karwariya3*, Sandeep Goyal4, T

SGVU J CLIM CHANGE WATER Vol. 4, 2017 pp. 9-12 Dwivedi et al. SGVU J CLIM CHANGE WATER Vol. 1 (2), 9-12 ISSN: 2347-7741 SCS-CN Method for Surface Runoff Calculation of Agricultural Watershed Area of Bhojtal Priyanka Dwivedi1, Abhishek Mishra2, Sateesh Karwariya3*, Sandeep Goyal4, T. Thomas5 1Research Trainee Centre for policy Studies, Associated with MPCST, Bhopal 2Research Associate Madhya Pradesh Council of Science and Technology, Bhopal (MP) 3*Research Associate Indian Institute of Soil Science, Bhopal (MP) 4Principle Scientist Madhya Pradesh Council of Science and Technology, Bhopal (MP) 5Scientist ‘C’ National Institute of Hydrology WALMI Campus, Bhopal *Corresponding author: [email protected] ABSTRACT The Upper Lake, (Bhojtal) is situated in the city Bhopal.Upper Lake is the major source of water for the city Bhopal. Economic as well as recreational activities of the city Bhopal are dependent on the water availability in the upper Bhopal Lake. This receives water as surface runoff only during monsoon period of each and every year. The upper lake has a catchment area of 375.55km2. The Land use Pattern of about 80% of the catchment is an agricultural area. Whereas 5% is of the forest and rest comes in urban area. Since the inset of monsoon in the catchment area is by 15th June in every year. The agricultural area starts contributing by the end of august. Whereas the lake start receiving surface runoff right from the beginning of monsoon season. Bhojtal Basin has a good surface hydro environment potential to reduce the water scarcity problem of the district. -

Rajdhani Thali Tuesday Offer Hyderabad

Rajdhani Thali Tuesday Offer Hyderabad Bereft and anopheline Wolf lures her Tiresias verbalized while Caesar ebonizing some serigraphs verily. Stamped Giavani sometimes fermentation,outwearies any he Hautes-Alpes gypped so awash. spangs tensely. Undigested Fred deepen democratically while Regen always despite his sigillation shallows Fresh food order this brand publish on thali tuesday offer hyderabad food Partner With us Menu Established in 2012 Socialise Fivestarchicken EVENTS & NEWS Stay Connected Offers. Order Food Online from Rajdhani Sujana Forum Mall Kukatpally and anxious it's menu for Home Delivery in Hyderabad Fastest delivery No minimum order GPS. Hyderabad Ph 040-23356366666290 Mobile 93964022 Vijayawada. Khandani Rajdhani has been between world's favourite thali since school has. Get its Discount of 10 at Khandani Rajdhani Kukatpally. Get contact information of Khandani Rajdhani Restaurant In. Rajdhani Thali RajdhaniThali Twitter. Tuesdays are cheaP Reviews Photos Rajdhani Thali. No doubt whether we have survived the thali tuesday. Avail an outstanding discount of 10 on labour bill at Khandani Rajdhani Kukatpally West. Rajdhani Tuesday Thali just Rs199- & 149- seleced. Tuesday Special Price Picture of Rajdhani Hyderabad. Authentic veg restaurants which is finger Licking North Indian cuisine. Visit Rajdhani Thali Mumbai Bangalore Pune Chennai Hyderabad Nashik and Bhopal on Tuesday for fishing The decline More outlets info. Here's an anthem to send a riot on the faces of women- who plan to left's an exciting. Rajdhani Thali Restaurant Hyderabad Rajdhani Thali Restaurant Kukatpally Get Menu Reviews Contact Location Phone Number Maps and burn for. This valentine s day learn from them on our outlets of having a los anuncios y no. -

Architecture of Central India 17 Days/16 Nights

Architecture of Central India 17 Days/16 Nights Activities Overnight Day 1 Fly U.S. to Delhi Delhi Day 2 Our first stop today will be Qutub Minar, the world’s tallest brick minaret, Delhi built to mark the site of the first Muslim kingdom in North India. We will next visit Humayun’s tomb, the first Persian tomb garden in India. Lunch in Connaught Place (Robert Tor Russell), which was built in 1931 as an upscale shopping complex for the British. The area is now full of interesting high rises, such as the Jeevan Bharati (Charles Correa) and the Statesman House. This afternoon, we will visit Jami Masjid, India’s largest mosque, built in 1656 by Emperor Shah Jahan. This will be followed by a rickshaw ride through Chandi Chowk, a maze of streets, shops and houses that date back to the 1600’s. Dinner at the Imperial Hotel, designed by D. J. Bromfield, an associate of Sir Edwin Lutyens. Day 3 In 1911, Lutyens was commissioned to design India’s new capital complex, Delhi and the result synthesizes Mughal motifs with Neo-Classical and Edwardian architectural styles. We will begin with a drive by the Secretariat and the Sansad Bhavan (Herbert Baker), the Rashtrapati Bhavan (Lutyens) and the Supreme Court (Ganesh Bhikaji Deolalikar). Our next stop is St. Martin’s Garrison Church (Arthur G. Shoesmith), followed by Raj Ghat (Vanu G. Bhuta), the site of Mahatma Gandhi’s cremation. We will have our lunch in the India Islamic Cultural Centre (S. K. Das), from which we can view the India Habitat Centre (Joseph Allen Stein). -

Guidelines for Relaxation to Travel by Airlines Other Than Air India

GUIDELINES FOR RELAXATION TO TRAVEL BY AIRLINES OTHER THAN AIR INDIA 1. A Permission Cell has been constituted in the Ministry of Civil Aviation to process the requests for seeking relaxation to travel by airlines other than Air India. 2. The Cell is functioning under the control of Shri B.S. Bhullar, Joint Secretary in the Ministry of Civil Aviation. (Telephone No. 011-24616303). In case of any clarification pertaining to air travel by airlines other than Air India, the following officers may be contacted: Shri M.P. Rastogi Shri Dinesh Kumar Sharma Ministry of Civil Aviation Ministry of Civil Aviation Rajiv Gandhi Bhavan Rajiv Gandhi Bhavan Safdarjung Airport Safdarjung Airport New Delhi – 110 003. New Delhi – 110 003. Telephone No : 011-24632950 Extn : 2873 Address : Ministry of Civil Aviation, Rajiv Gandhi Bhavan, Safdarjung Airport, New Delhi – 110 003. 3. Request for seeking relaxation is required to be submitted in the Proforma (Annexure-I) to be downloaded from the website, duly filled in, scanned and mailed to [email protected]. 4. Request for exemption should be made at least one week in advance from date of travel to allow the Cell sufficient time to take action for convenience of the officers. 5. Sectors on which General/blanket relaxation has been accorded are available at Annexure-II, III & IV. There is no requirement to seek relaxation forthese sectors. 6. Those seeking relaxation on ground of Non-Availability of Seats (NAS) must enclose NAS Certificate issued by authorized travel agents – M/s BalmerLawrie& Co., Ashok Travels& Tours and IRCTC (to the extent IRCTC is authorized as per DoP&T OM No. -

THE COAT of ARMS an Heraldic Journal Published Twice Yearly by the Heraldry Society the COAT of ARMS the Journal of the Heraldry Society

Third Series Vol. II part 2. ISSN 0010-003X No. 212 Price £12.00 Autumn 2006 THE COAT OF ARMS an heraldic journal published twice yearly by The Heraldry Society THE COAT OF ARMS The journal of the Heraldry Society Third series Volume II 2006 Part 2 Number 212 in the original series started in 1952 The Coat of Arms is published twice a year by The Heraldry Society, whose registered office is 53 High Street, Burnham, Slough SL1 7JX. The Society was registered in England in 1956 as registered charity no. 241456. Founding Editor † John Brooke-Little, C.V.O., M.A., F.H.S. Honorary Editors C. E. A. Cheesman, M.A., PH.D., Rouge Dragon Pursuivant M. P. D. O'Donoghue, M.A., Bluemantle Pursuivant Editorial Committee Adrian Ailes, B.A., F.S.A., F.H.S. Jackson W. Armstrong, B.A. Andrew Hanham, B.A., PH.D Advertizing Manager John Tunesi of Liongam PLATE 4 Osmond Barnes, Chief Herald at the Imperial Assemblage at Delhi, 1876-7 Private Collection. See page 108. HERALDS AT THE DELHI DURBARS Peter O 'Donoghue Three great imperial durbars took place on the Ridge outside Delhi during the height of the British Raj, on a site which was associated with the heroics of the Mutiny. The first durbar, in 1876-77, proclaimed Queen Victoria as Empress of India, whilst the second and third, in 1902-3 and 1911, proclaimed the accessions of Edward VII and George V respectively. All three drew upon Indian traditions of ceremonial meetings or durbars between rulers and ruled, and in particular upon the Mughal Empire's manner of expressing its power to its subject princes. -

Clients' Satisfaction with Anti Retroviral Therapy Services at Hamidia Hospital Bhopal

pISSN: 0976 3325 eISSN: 2229 6816 Original Article.. CLIENTS’ SATISFACTION WITH ANTI RETROVIRAL THERAPY SERVICES AT HAMIDIA HOSPITAL BHOPAL Bhagat Vimal Kishor1, Pal D K2, Lodha Rama S1, Bankwar Vishal1 1Assitant professor, Department of Community Medicine, LNMC Medical College, Bhopal 2Professor & Head, Departmnet of Community Medicine, Gandhi Medical College, Bhopal. Correspondence: Dr Vimal Kishor Bhagat C/O Dr B Minj, A-16, Nikhil Bunglow, Phase-3, Hosangabad Road, Bhopal, Madhya Pradesh E-mail address: [email protected] Mobile: 09425906060 ABSTRACT Background: The HIV/AIDS pandemic is a major public health problem with an estimated 33.33 million people living with the virus globally. Free antiretroviral treatment was initiated in India 2004. Patients’ satisfaction is one of the commonly used outcome measures of patient care. Objective: To assess the satisfaction of people living with HIV/AIDS with services provided at anti retroviral therapy Centre Hamidia Hospital Bhopal. Material and Methods: A hospital based cross-sectional study was undertaken from August 2008 to July 2009 on all the registered people living with HIV/AIDS (PLWHA) following antiretroviral treatment at Hamidia Hospital Bhopal. Data was collected and by using pre-designed & pre-tested questionnaire and analyzed using Epi-info version 3.5.3. Results: For most of the questions regarding satisfaction on the care services of the center, participants responded positively (excellent & good).The overall mean satisfaction score was “Excellent”. Conclusion: The services of the Center were rated positively (Excellent and above).The hospital management should work to strengthen the clinic services by helping the ART clinic staff to involve patients in the treatment process and recognize their opinions on follow up. -

SUMMER HOLIDAY HOMEWORK CLASS-XII C “A Vacation Is Having Nothing to Do but All Day to Do in It

WORLD WAY INTERNATIONAL SCHOOL BHOPAL SUMMER HOLIDAY HOMEWORK CLASS-XII C “A vacation is having nothing to do but all day to do in it. The summer holidays are a great time to enjoy experiences and to learn new things in our life” Dear Students, Holiday is the time that we all eagerly waiting for. We all make plans to enjoy, to relax. In this summer vacation the Holiday Homework is designed by the mentors of the school to explore and learn new things. The school ensure you that if you work out the following assignments, it will lead you to gain new knowledge and also enable you to prepare yourself for various exams in the session 2021-22. Unit test 1 will be assessed through this assignment. REMEMBER: Neatnessandpresentationarecommonparametersfor all the assignments. Complete your work andsubmitaccordingtothe date schedule given below. Late submission is not acceptable and you will be losing the marks/grades for the same if you miss the date. Holidayhomeworkwillbeassessedonnecessaryparametersand marks/grade will be awarded for UT-1 (Unit Test-1) for2021-22. General Instructions:- • Summer vacations begin from 1st May 2021. • School Reopening Date: - 07th June 2021 • All works can be done in separate register. • Board Practical work can be done in separate practical files as per the subject need. • All work should be in hand written only. • For uploading video, separate google form link will be provided. • Attempt all skill-basedquestions. • Support your answer according to the need of yourquestions. • Prepare VIDEO/AUDIO CLIPS where every it is necessary. Dates for holiday homework submission:- S.NO DATE DAY SUBJECTS 1 10th June 21 Thursday English, Economics 2 12th June 21 Saturday Chemistry + Business studies + History 3 14th June 21 Monday Physics + Accountancy + Political science 4 16th June 21 Wednesday Maths + Physical Edu. -

The Bhopal Disaster Litigation: It's Not Over Yet

NORTH CAROLINA JOURNAL OF INTERNATIONAL LAW Volume 16 Number 2 Article 5 Fall 1991 The Bhopal Disaster Litigation: It's Not over Yet Tim Covell Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.unc.edu/ncilj Recommended Citation Tim Covell, The Bhopal Disaster Litigation: It's Not over Yet, 16 N.C. J. INT'L L. 279 (1991). Available at: https://scholarship.law.unc.edu/ncilj/vol16/iss2/5 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Carolina Law Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in North Carolina Journal of International Law by an authorized editor of Carolina Law Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Bhopal Disaster Litigation: It's Not over Yet Cover Page Footnote International Law; Commercial Law; Law This article is available in North Carolina Journal of International Law: https://scholarship.law.unc.edu/ncilj/vol16/ iss2/5 The Bhopal Disaster Litigation: It's Not Over Yet Tim Covell* I. Introduction On December 3, 1984, forty tons' of deadly methyl isocyanate gas escaped from a Union Carbide plant and spread over the city of Bhopal, India.2 As many as 2,100 people died soon after the gas leak and approximately 200,000 suffered injuries, 3 making it the worst in- dustrial disaster to date.4 As of December 1990, the official death toll reached 3,828. 5 The legal community immediately became in- volved, filing the first suit against Union Carbide Corporation (UCC) in the United States four days after the disaster.6 Eventually, injured parties filed 145 lawsuits for damages against UCC in the United 7 States, and 6,500 against Union Carbide India, Ltd. -

Urdu in Hyderabad State*

tariq rahman Urdu in Hyderabad State* The state of Hyderabad was carved out in 1724 by the Asif Jahis (Āṣif Jāhīs), the governors of the Mughal emperors in the Deccan, when they became powerful enough to set themselves up as rulers in their own right. The Nizams1ófrom Mīr Qamruíd-Dīn Khān (1724ñ48) until the sixth ruler of the house Mīr Maḥbūb ʿAlī Khān (1869ñ1911)óused Persian as their court language, in common with the prevailing fashion of their times, though they spoke Urdu at home. Persian was, however, replaced by Urdu in some domains of power, such as law courts, administration and education, toward the end of the nineteenth century. The focus of this article is on the manner in which this transition took place. This phenomenon, which may be called the ìUrduizationî of the state, had important consequences. Besides the historical construction of events, an attempt will be made to understand these consequences: the link of ìUrduizationî with power, the construction of Muslim identity, and socio- economic class. Moreover, the effect of ìUrduizationî on the local languages of Hyderabad will also be touched on. *The author is grateful to the Higher Education Commission of Pakistan for a grant to carry out research for this article in India. 1The Nizams who actually ruled were the first seven; the last in the line carried the title until 1971 but did not rule: 1) Mīr Qamaruíd-Dīn Khān Niāmuíl- Mulk Āṣaf Jāh I (r. 1724–48); 2) Mīr Niām ʿAlī Khān Āṣaf Jāh II (r. 1762–1803); 3) Mīr Akbar ʿAlī Khān Sikandar Jāh III (r.