Revised Henle I Guide Units I-V PROOF2 Proofed by Jen.Indd

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Strategy of Case-Marking

Case marking strategies Helen de Hoop & Andrej Malchukov1 Radboud University Nijmegen DRAFT January 2006 Abstract Two strategies of case marking in natural languages are discussed. These are defined as two violable constraints whose effects are shown to converge in the case of differential object marking but diverge in the case of differential subject marking. The strength of the case bearing arguments will be shown to be of utmost importance for case marking as well as voice alternations. The strength of arguments can be viewed as a function of their discourse prominence. The analysis of the case marking patterns we find cross-linguistically is couched in a bidirectional OT analysis. 1. Assumptions In this section we wish to put forward our three basic assumptions: (1) In ergative-absolutive systems ergative case is assigned to the first argument x of a two-place relation R(x,y). (2) In nominative-accusative systems accusative case is assigned to the second argument y of a two-place relation R(x,y). (3) Morphologically unmarked case can be the absence of case. The first two assumptions deal with the linking between the first (highest) and second (lowest) argument in a transitive sentence and the type of case marking. For reasons of convenience, we will refer to these arguments quite sloppily as the subject and the object respectively, although we are aware of the fact that the labels subject and object may not be appropriate in all contexts, dependent on how they are actually defined. In many languages, ergative and accusative case are assigned only or mainly in transitive sentences, while in intransitive sentences ergative and accusative case are usually not assigned. -

Does English Have a Genitive Case? [email protected]

2. Amy Rose Deal – University of Massachusetts, Amherst Does English have a genitive case? [email protected] In written English, possessive pronouns appear without ’s in the same environments where non-pronominal DPs require ’s. (1) a. your/*you’s/*your’s book b. Moore’s/*Moore book What explains this complementarity? Various analyses suggest themselves. A. Possessive pronouns are contractions of a pronoun and ’s. (Hudson 2003: 603) B. Possessive pronouns are inflected genitives (Huddleston and Pullum 2002); a morphological deletion rule removes clitic ’s after a genitive pronoun. Analysis A consists of a single rule of a familiar type: Morphological Merger (Halle and Marantz 1993), familiar from forms like wanna and won’t. (His and its contract especially nicely.) No special lexical/vocabulary items need be postulated. Analysis B, on the other hand, requires a set of vocabulary items to spell out genitive case, as well as a rule to delete the ’s clitic following such forms, assuming ’s is a DP-level head distinct from the inflecting noun. These two accounts make divergent predictions for dialects with complex pronominals such as you all or you guys (and us/them all, depending on the speaker). Since Merger operates under adjacency, Analysis A predicts that intervention by all or guys should bleed the formation of your: only you all’s and you guys’ are predicted. There do seem to be dialects with this property, as witnessed by the American Heritage Dictionary (4th edition, entry for you-all). Call these English 1. Here, we may claim that pronouns inflect for only two cases, and Merger operations account for the rest. -

Animacy, Definiteness, and Case in Cappadocian and Other

Animacy, definiteness, and case in Cappadocian and other Asia Minor Greek dialects* Mark Janse Ghent University and Roosevelt Academy, Middelburg This article discusses the relation between animacy, definiteness, and case in Cappadocian and several other Asia Minor Greek dialects. Animacy plays a decisive role in the assignment of Greek and Turkish nouns to the various Cappadocian noun classes. The development of morphological definiteness is due to Turkish interference. Both features are important for the phenom- enon of differential object marking which may be considered one of the most distinctive features of Cappadocian among the Greek dialects. Keywords: Asia Minor Greek dialectology, Cappadocian, Farasiot, Lycaonian, Pontic, animacy, definiteness, case, differential object marking, Greek–Turkish language contact, case typology . Introduction It is well known that there is a crosslinguistic correlation between case marking and animacy and/or definiteness (e.g. Comrie 1989:128ff., Croft 2003:166ff., Linguist List 9.1653 & 9.1726). In nominative-accusative languages, for in- stance, there is a strong tendency for subjects of active, transitive clauses to be more animate and more definite than objects (for Greek see Lascaratou 1994:89). Both animacy and definiteness are scalar concepts. As I am not con- cerned in this article with pronouns and proper names, the person and referen- tiality hierarchies are not taken into account (Croft 2003:130):1 (1) a. animacy hierarchy human < animate < inanimate b. definiteness hierarchy definite < specific < nonspecific Journal of Greek Linguistics 5 (2004), 3–26. Downloaded from Brill.com09/29/2021 09:55:21PM via free access issn 1566–5844 / e-issn 1569–9856 © John Benjamins Publishing Company 4 Mark Janse With regard to case marking, there is a strong tendency to mark objects that are high in animacy and/or definiteness and, conversely, not to mark ob- jects that are low in animacy and/or definiteness. -

Possessive Constructions in Modern Low Saxon

POSSESSIVE CONSTRUCTIONS IN MODERN LOW SAXON a thesis submitted to the department of linguistics of stanford university in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of master of arts Jan Strunk June 2004 °c Copyright by Jan Strunk 2004 All Rights Reserved ii I certify that I have read this thesis and that, in my opinion, it is fully adequate in scope and quality as a thesis for the degree of Master of Arts. Joan Bresnan (Principal Adviser) I certify that I have read this thesis and that, in my opinion, it is fully adequate in scope and quality as a thesis for the degree of Master of Arts. Tom Wasow I certify that I have read this thesis and that, in my opinion, it is fully adequate in scope and quality as a thesis for the degree of Master of Arts. Dan Jurafsky iii iv Abstract This thesis is a study of nominal possessive constructions in modern Low Saxon, a West Germanic language which is closely related to Dutch, Frisian, and German. After identifying the possessive constructions in current use in modern Low Saxon, I give a formal syntactic analysis of the four most common possessive constructions within the framework of Lexical Functional Grammar in the ¯rst part of this thesis. The four constructions that I will analyze in detail include a pronominal possessive construction with a possessive pronoun used as a determiner of the head noun, another prenominal construction that resembles the English s-possessive, a linker construction in which a possessive pronoun occurs as a possessive marker in between a prenominal possessor phrase and the head noun, and a postnominal construction that involves the preposition van/von/vun and is largely parallel to the English of -possessive. -

The Term Declension, the Three Basic Qualities of Latin Nouns, That

Chapter 2: First Declension Chapter 2 covers the following: the term declension, the three basic qualities of Latin nouns, that is, case, number and gender, basic sentence structure, subject, verb, direct object and so on, the six cases of Latin nouns and the uses of those cases, the formation of the different cases in Latin, and the way adjectives agree with nouns. At the end of this lesson we’ll review the vocabulary you should memorize in this chapter. Declension. As with conjugation, the term declension has two meanings in Latin. It means, first, the process of joining a case ending onto a noun base. Second, it is a term used to refer to one of the five categories of nouns distinguished by the sound ending the noun base: /a/, /ŏ/ or /ŭ/, a consonant or /ĭ/, /ū/, /ē/. First, let’s look at the three basic characteristics of every Latin noun: case, number and gender. All Latin nouns and adjectives have these three grammatical qualities. First, case: how the noun functions in a sentence, that is, is it the subject, the direct object, the object of a preposition or any of many other uses? Second, number: singular or plural. And third, gender: masculine, feminine or neuter. Every noun in Latin will have one case, one number and one gender, and only one of each of these qualities. In other words, a noun in a sentence cannot be both singular and plural, or masculine and feminine. Whenever asked ─ and I will ask ─ you should be able to give the correct answer for all three qualities. -

Class Slides

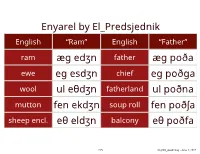

Enyarel by El_Predsjednik English “Ram” English “Father” ram æg edʒn father æg poða ewe eg esdʒn chief eg poðga wool ul eθdʒn fatherland ul poðna mutton fen ekdʒn soup roll fen poðʃa sheep encl. eθ eldʒn balcony eθ poðfa 215 ling183_week2.key - June 1, 2017 HIGH VALYRIAN 216 ling183_week2.key - June 1, 2017 The common language of the Valyrian Freehold, a federation in Essos that was destroyed by the Doom before the series begins. 217 ling183_week2.key - June 1, 2017 218 ling183_week2.key - June 1, 2017 ??????? High Valyrian ?????? 219 ling183_week2.key - June 1, 2017 Valar morghulis. “ALL men MUST die.” Valar dohaeris. “ALL men MUST serve.” 220 ling183_week2.key - June 1, 2017 Singular, Plural, Collective 221 ling183_week2.key - June 1, 2017 Number Marking Definite Indefinite Small Number Singular Large Number Collective Plural 222 ling183_week2.key - June 1, 2017 Number Marking Definite Indefinite Small Number Singular Paucal Large Number Collective Plural 223 ling183_week2.key - June 1, 2017 Head Final ADJ — N kastor qintir “green turtle” 224 ling183_week2.key - June 1, 2017 Head Final ADJ — N *val kaːr “man heap” 225 ling183_week2.key - June 1, 2017 Head Final ADJ — N *valhaːr > *valhar > valar “all men” 226 ling183_week2.key - June 1, 2017 Head Final ADJ — N *val ont > *valon > valun “man hand > some men” 227 ling183_week2.key - June 1, 2017 SOUND CHANGE Dispreference for certain _# Cs, e.g. voiced stops, laterals, voiceless non- coronals, etc. 228 ling183_week2.key - June 1, 2017 SOUND CHANGE Dispreference for monosyllabic words— especially -

The Accusative Case the Accusative Case Is Applied to the Direct Object of the Verb

The Accusative Case The accusative case is applied to the direct object of the verb. For example “I studied the .Notice several things about this sentence درس ُت الكتا ب book” is rendered in Arabic as is not used in the sentence. Such pronouns are usually not أنا ”,First, the pronoun for “I used, since the verb conjugation tells us who the subject is. These pronouns are used sometimes for emphasis. Second, notice that I left most of the verb unvowelled. The only vowel I used is the vowel that tells you for which person the verb is being conjugated. Sometimes you may see such a vowel included in an authentic Arab text if there is a chance of ambiguity. However, usually the verb, like all words, will be completely unvocalized. Notice that the verb ends in a vowel and that the vowel will elide the hamza on the definite article. ends in a fatha. The fatha is the accusative case الكتا ب ,Fourth, the direct object of the verb marker. I studied a document.” Notice that two fathas are used“ درس ُت وثيقة :Look at this sentence here. The second fatha gives us the nunation. This is just like the other two cases, nominative and genitive where the second dhanuna and second kasra provide the nunation. So, we use one fatha if the word is definite and two fathas if the word is indefinite. But there درست كتابا :is just a little bit more. Look at the following This is “I studied a book.” Here the indefinite direct object ends in two fathas but we have also added an alif. -

Introduction to Latin Nouns 1. Noun Entries – Chapter 3, LFCA Example

Session A3: Introduction to Latin Nouns 1. Noun entries – Chapter 3, LFCA When a Latin noun is listed in a dictionary it provides three pieces of information: The nominative singular, the genitive singular, and the gender. The first form, called nominative (from Latin nömen, name) is the means used to list, or name, words in a dictionary. The second form, the genitive (from Latin genus, origin, kind or family), is used to find the stem of the noun and to determine the declension, or noun family to which it belongs. To find the stem of a noun, simply look at the genitive singular form and remove the ending –ae. The final abbreviation is a reference to the noun’s gender, since it is not always evident by the noun’s endings. Example: fëmina, fëminae, f. woman stem = fëmin/ae 2. Declensions – Chapters 3 – 10, LFCA Just as verbs are divided up into families or groups called conjugations, so also nouns are divided up into groups that share similar characteristics and behavior patterns. A declension is a group of nouns that share a common set of inflected endings, which we call case endings (more on case later). The genitive reveals the declension or family of nouns from which a word originates. Just as the infinitive is different for each conjugation, the genitive singular is unique to each declension. 1 st declension mënsa, mënsae 2 nd declension lüdus, lüdï ager, agrï dönum, dönï 3 rd declension vöx, vöcis nübës, nübis corpus, corporis 4 th declension adventus, adventüs cornü, cornüs 5 th declension fidës, fideï Practice: 1. -

Introduction to Case, Animacy and Semantic Roles: ALAOTSIKKO

1 Introduction to Case, animacy and semantic roles Please cite this paper as: Kittilä, Seppo, Katja Västi and Jussi Ylikoski. (2011) Introduction to case, animacy and semantic roles. In: Kittilä, Seppo, Katja Västi & Jussi Ylikoski (Eds.), Case, Animacy and Semantic Roles, 1-26. Amsterdam: John Benjamins. Seppo Kittilä Katja Västi Jussi Ylikoski University of Helsinki University of Oulu University of Helsinki University of Helsinki 1. Introduction Case, animacy and semantic roles and different combinations thereof have been the topic of numerous studies in linguistics (see e.g. Næss 2003; Kittilä 2008; de Hoop & de Swart 2008 among numerous others). The current volume adds to this list. The focus of the chapters in this volume lies on the effects that animacy has on the use and interpretation of cases and semantic roles. Each of the three concepts discussed in this volume can also be seen as somewhat problematic and not always easy to define. First, as noted by Butt (2006: 1), we still have not reached a full consensus on what case is and how it differs, for example, from 2 the closely related concept of adpositions. Second, animacy, as the label is used in linguistics, does not fully correspond to a layperson’s concept of animacy, which is probably rather biology-based (see e.g. Yamamoto 1999 for a discussion of the concept of animacy). The label can therefore, if desired, be seen as a misnomer. Lastly, semantic roles can be considered one of the most notorious labels in linguistics, as has been recently discussed by Newmeyer (2010). There is still no full consensus on how the concept of semantic roles is best defined and what would be the correct or necessary number of semantic roles necessary for a full description of languages. -

Chapter 4 Second Declension Masculine Nouns 4.1 Nouns

Chapter 4 _______________________________ Second Declension Masculine Nouns _____________________ 4.1 Nouns are names for things (book, dog), persons (girl, John), places (field, Paris), qualities (truth) . In a sentence, nouns can be used to tell us "who" is doing what (the action of the verb) to "whom", with "what". e.g. "The dog chased the cat up the tree." English nouns usually show "Number" : Singular (one thing or person) or Plural (more than one). They may do this by changing in several ways. e.g. dog, dogs; man, men; mouse, mice; child, children; leaf, leaves Greek nouns will do the same sort of thing but, thankfully, there are fewer variations in the way a plural noun is formed from a singular. In both English and Greek there are three "grammatical genders" associated with nouns : Masculine, Feminine, and Neuter. The grammatical gender of an English noun is usually the same as the sex of the thing named. Masculine : boy, lad, stallion, boar, bull, John, Peter, colt, ram, master, hero Feminine : girl, lass, mare, cow, Mary, Jane, filly, ewe, mistress, heroine, vixen Neuter : book, table, patience, word, animal, tree, field, metal The grammatical gender of Greek nouns is less tied to the sex of an object. They are grouped into families of nouns with the same endings - the families are called "Declensions" For example, there is a large group of nouns which all end in -oς. This family includes many masculine names such as Πέτρoς, Παῦλoς, Mάρκoς. So this whole family of nouns ending in -oς is treated as masculine (with a few exceptions, which we shall meet in a later chapter). -

Introduction to Gothic

Introduction to Gothic By David Salo Organized to PDF by CommanderK Table of Contents 3..........................................................................................................INTRODUCTION 4...........................................................................................................I. Masculine 4...........................................................................................................II. Feminine 4..............................................................................................................III. Neuter 7........................................................................................................GOTHIC SOUNDS: 7............................................................................................................Consonants 8..................................................................................................................Vowels 9....................................................................................................................LESSON 1 9.................................................................................................Verbs: Strong verbs 9..........................................................................................................Present Stem 12.................................................................................................................Nouns 14...................................................................................................................LESSON 2 14...........................................................................................Strong -

Objective and Subjective Genitives

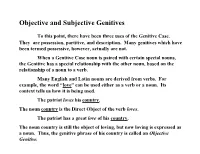

Objective and Subjective Genitives To this point, there have been three uses of the Genitive Case. They are possession, partitive, and description. Many genitives which have been termed possessive, however, actually are not. When a Genitive Case noun is paired with certain special nouns, the Genitive has a special relationship with the other noun, based on the relationship of a noun to a verb. Many English and Latin nouns are derived from verbs. For example, the word “love” can be used either as a verb or a noun. Its context tells us how it is being used. The patriot loves his country. The noun country is the Direct Object of the verb loves. The patriot has a great love of his country. The noun country is still the object of loving, but now loving is expressed as a noun. Thus, the genitive phrase of his country is called an Objective Genitive. You have actually seen a number of Objective Genitives. Another common example is Rex causam itineris docuit. The king explained the cause of the journey (the thing that caused the journey). Because “cause” can be either a noun or a verb, when it is used as a noun its Direct Object must be expressed in the Genitive Case. A number of Latin adjectives also govern Objective Genitives. For example, Vir miser cupidus pecuniae est. A miser is desirous of money. Some special nouns and adjectives in Latin take Objective Genitives which are more difficult to see and to translate. The adjective peritus, -a, - um, meaning “skilled” or “experienced,” is one of these: Nautae sunt periti navium.