Material Cultural Correlates of the Athapaskan Expansion: a Cross-Disciplinary Approach

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Eyak Podcast Gr: 9-12 (Lesson 1)

HONORING EYAK: EYAK PODCAST GR: 9-12 (LESSON 1) Elder Quote: “We have a dictionary pertaining to the Eyak language, since there are so few of us left. That’s something my mom neve r taught me, was the Eyak language. It is altogether different than the Aleut. There are so few of us left that they have to do a book about the Eyak Tribe. There are so many things that my mother taught me, like smoking fish, putting up berries, and how to keep our wild meat. I have to show you; I can’t tell you how it is done, but anything you want to know I’ll tell you about the Eyak tribe.” - Rosie Lankard, 1980i Grade Level: 9-12 Overview: Heritage preservation requires both active participation and awareness of cultural origins. The assaults upon Eyak culture and loss of fluent Native speakers in the recent past have made the preservation of Eyak heritage even more challenging. Here students actively investigate and discuss Eyak history and culture to inspire their production of culturally insightful podcasts. Honoring Eyak Page 1 Cordova Boy in sealskin, Photo Courtesy of Cordova Historical Society Standards: AK Cultural: AK Content: CRCC: B1: Acquire insights from other Geography B1: Know that places L1: Students should understand the cultures without diminishing the integrity have distinctive characteristics value and importance of the Eyak of their own. language and be actively involved in its preservation. Lesson Goal: Students select themes or incidents from Eyak history and culture to create culturally meaningful podcasts. Lesson Objectives: Students will: Review and discuss Eyak history. -

Chapter 3. from Nature to “Culture”

Georges Chapouthier The Mosaic Theory of Natural Complexity A scientific and philosophical approach Éditions des maisons des sciences de l’homme associées Chapter 3. From Nature to “Culture” Publisher: Éditions des maisons des sciences de l’homme associées Place of publication: Éditions des maisons des sciences de l’homme associées Year of publication: 2018 Published on OpenEdition Books: 10 April 2018 Serie: Collection interdisciplinaire EMSHA Electronic ISBN: 9782821895744 http://books.openedition.org Electronic reference CHAPOUTHIER, Georges. Chapter 3. From Nature to “Culture” In: The Mosaic Theory of Natural Complexity: A scientific and philosophical approach [online]. La Plaine-Saint-Denis: Éditions des maisons des sciences de l’homme associées, 2018 (generated 10 septembre 2020). Available on the Internet: <http://books.openedition.org/emsha/210>. ISBN: 9782821895744. Chapter 3 From Nature to “Culture” In the first two chapters we presented evidence of general principles involved in complexity as mosaics as seen in very different fields. It is interesting to observe that the two distinguishing features which are the pride of the human race, i.e. the brain and highly complex thought, are built on the same foundations as the rest of the living world – juxtaposition and integration. In the present chapter, I shall analyze the comparison in terms of nature and culture, with the brain referring to nature and the mind referring to culture. English-speakers often make the distinction between nature and nurture, but I prefer to use the continental word “culture”, for both humans and animals. The discussion in the previous chapter included phenomena of the mind such as language, music, drawing, philosophy and literature, and was already what I consider to be a cultural approach. -

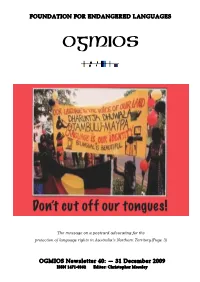

A PDF Combined with Pdfmergex

!"#$%&'("$)!"*)+$%&$,+*+%)-&$,#&,+.) ) OGMIOS The message on a postcard advocating for the protection of language rights in Australia’s Northern Territory (Page 3) ",/(".)$012304405)678)9):;)%0<0=>05)?77@) (..$);6A;B7:C?))))))+DE4F58)GH5E24FIH05)/F2030J) 2 DEBFD<'C4G"64$$4+'HI,'J'KL'=4/4M14+'NIIO' F<<C'LHPLQIKRN''''''()#$*+,'07+#"$*:74+'B*"464;' !""#"$%&$'()#$*+,'!)+#%&*'-+."/*$$' 0*&$+#1.$#&2'()#$*+",'3*24+'564&/78'9*"4:7'56;$748'<4+4&%'=>!2*"$#&*8'07+#"$*:74+'?%)@#46)8'A+%&/#"'B'?.6$8'' C#/7*6%"'D"$64+8'!&)+4%'3#$$4+' ' !"#$%&$'$()'*+,$"-'%$.' /012,3()+'14.' ' 07+#"$*:74+'B*"464;8' A*.&)%$#*&'@*+'(&)%&24+4)'X%&2.%24"8' O'S4"$)4&4'0+4"/4&$8' LPN'5%#61+**Y'X%&48'' 0%T4+"7%M'?4#27$"8' 5%$7'5!L'P!!8'(&26%&)' 34%)#&2'3EH'P?=8'(&26%&)' &*"$64+V/7#1/7%W)4M*&W/*W.Y'' /7+#"M*"464;UIV;%7**W/*M'' 'GGGW*2M#*"W*+2' The Austronesian Languages......................................... 19! LW'()#$*+#%6 3! Immersion – a film on endangered languages ............... 19! Cover Story: Northern Territory’s small languages sidelined from schools ...................................................... 3! RW'\6%/4"'$*'2*'*&'$74'S41 20! NW! =4T46*:M4&$'*@'$74'A*.&)%$#*& 4! Irish upside down............................................................ 20! Resolution of the FEL XIII Conference, Khorog, Tajikistan, OW'A*+$7/*M#&2'4T4&$" 21! 26, September, 2009 ........................................................ 4! HRELP Workshop: Endangered Languages, endangered FEL and UNESCO Atlas partnership................................ 4! knowledge & sustainability............................................. -

33 Contact and North American Languages

9781405175807_4_033 1/15/10 5:37 PM Page 673 33 Contact and North American Languages MARIANNE MITHUN Languages indigenous to the Americas offer some good opportunities for inves- tigating effects of contact in shaping grammar. Well over 2000 languages are known to have been spoken at the time of first contacts with Europeans. They are not a monolithic group: they fall into nearly 200 distinct genetic units. Yet against this backdrop of genetic diversity, waves of typological similarities suggest pervasive, longstanding multilingualism. Of particular interest are similarities of a type that might seem unborrowable, patterns of abstract structure without shared substance. The Americas do show the kinds of contact effects common elsewhere in the world. There are some strong linguistic areas, on the Northwest Coast, in California, in the Southeast, and in the Pueblo Southwest of North America; in Mesoamerica; and in Amazonia in South America (Bright 1973; Sherzer 1973; Haas 1976; Campbell, Kaufman, & Stark 1986; Thompson & Kinkade 1990; Silverstein 1996; Campbell 1997; Mithun 1999; Beck 2000; Aikhenvald 2002; Jany 2007). Numerous additional linguistic areas and subareas of varying sizes and strengths have also been identified. In some cases all domains of language have been affected by contact. In some, effects are primarily lexical. But in many, there is surprisingly little shared vocabulary in contrast with pervasive structural parallelism. The focus here will be on some especially deeply entrenched structures. It has often been noted that morphological structure is highly resistant to the influence of contact. Morphological similarities have even been proposed as better indicators of deep genetic relationship than the traditional comparative method. -

Cruikshank Athapaska

." '- l,,\ \ ( , c.. " j" ~ i' .' NATIONAL MUSEUM MUSEE NATIONAL OF MAN DE L:HOMME .MERCURY SERIES COLLECTION MERCURE CANADIAN ETHNOLOGY SERVICE LE SERVICE CANADIEN D'ETHNOLOGIE PAPER No.57 DOSSIER No.57 ATHAPASKAN WOMEN: Lives and Legends JULlE CRUIKSHANK NATIONAL MUSEUMS OF CANADA MUSEES NATIONAUX DU CANADA OTTAWA 1979 r-------~- ------.~ National Museum of Man Musee national de l'Honme National HuseUllE of Canada Musees nationaux du Canada Board of Trustees Conseil d' Administration Dr. Sean B 0 Murphy Chainnan Juge Ren.e J 0 Marin Vice-president Mo Roger B 0 Hanel Merrbre Mere Ginette Gadoury Hercbre Mr 0 MiChael CoD. Habbs Menher Mr. GcMer !1arkle Merrber Mo Paul Ho Ianan Menbre Mr 0 Richard I-ioHo Alway Merrber Mr 0 Robert Go MacLeod Merrber Mr 0 Ian Co Clark SecretaIy General Secretaire general Dr 0 William Eo Taylor, Jr. Director Directeur National Museum of Man Musee national de l' Honme Ao McFadyen ClaIk Olief Chef Canadian Ethnology Service Service canadien d' Ethnologie Dr 0 David Wo Zi.mrerly General Editor Editeur general Canadian Ethnology Service Service canadien d' Etlmologie Cravn Copyright Reserved © Droits reserves au nom de la Couronne NATIONAL MUSEUM MUSEE NATIONAL OF MAN DE ~HOMME MERCURY SERIES COLLECTION MERCURE ISSN 0316-1854 CANADIAN ETHNOLOGY SERVICE LE SERVICE CANADIEN D'ETHNOLOGIE PAPER No.57 DOSSIER No.57 ISSN 0316 -1862 ATHAPASKAN WOMEN: Lives and Legends JULlE CRUIKSHANK NATIONAL MUSEUMS OF CANADA MUSEES NATIONAUX DU CANADA OTTAWA 1979 OB.JEX:T OF THE MERCURY SERIES '!he Mercm:y Series is a publication of the National Museum of Man, National MuseUIIE of Canada, designed to pennit the rapid dissemination of information pertaining to those disciplines for which the National Museum of Man is responsible. -

Curriculum and Resources for First Nations Language Programs in BC First Nations Schools

Curriculum and Resources for First Nations Language Programs in BC First Nations Schools Resource Directory Curriculum and Resources for First Nations Language Programs in BC First Nations Schools Resource Directory: Table of Contents and Section Descriptions 1. Linguistic Resources Academic linguistics articles, reference materials, and online language resources for each BC First Nations language. 2. Language-Specific Resources Practical teaching resources and curriculum identified for each BC First Nations language. 3. Adaptable Resources General curriculum and teaching resources which can be adapted for teaching BC First Nations languages: books, curriculum documents, online and multimedia resources. Includes copies of many documents in PDF format. 4. Language Revitalization Resources This section includes general resources on language revitalization, as well as resources on awakening languages, teaching methods for language revitalization, materials and activities for language teaching, assessing the state of a language, envisioning and planning a language program, teacher training, curriculum design, language acquisition, and the role of technology in language revitalization. 5. Language Teaching Journals A list of journals relevant to teachers of BC First Nations languages. 6. Further Education This section highlights opportunities for further education, training, certification, and professional development. It includes a list of conferences and workshops relevant to BC First Nations language teachers, and a spreadsheet of post‐ secondary programs relevant to Aboriginal Education and Teacher Training - in BC, across Canada, in the USA, and around the world. 7. Funding This section includes a list of funding sources for Indigenous language revitalization programs, as well as a list of scholarships and bursaries available for Aboriginal students and students in the field of Education, in BC, across Canada, and at specific institutions. -

Language Archives: They’Re Not Just for Linguists Any More Gary Holton Alaska Native Language Center, Fairbanks

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by ScholarSpace at University of Hawai'i at Manoa Language Documentation & Conservation Special Publication No. 3 (August 2012): Potentials of Language Documentation: Methods, Analyses, and Utilization, ed. by Frank Seifart, Geoffrey Haig, Nikolaus P. Himmelmann, Dagmar Jung, Anna Margetts, and Paul Trilsbeek, pp. 105–110 http://nflrc.hawaii.edu/ldc/sp03/ 14 http://hdl.handle.net/10125/4523 Language archives: They’re not just for linguists any more Gary Holton Alaska Native Language Center, Fairbanks While many language archives were originally conceived for the purpose of preserving linguistic data, these data have the potential to inform knowledge beyond the narrow field of linguistics. Today language archives are being used by people without formal linguistic training for purposes not necessarily envisioned by the original creators of the language documentation. The DoBeS Archive is particularly well-placed to become an important resource for cultural documentation, since many of the DoBeS projects have been interdisciplinary in nature, documenting language within its broader social and cultural context. In this paper I present a perspective from a legacy archive created well before the modern era of digital language documentation exemplified by the DoBeS program. In particular, I describe two types of non-linguistic uses which are becoming increasingly important at the Alaska Native Language Archive. 1. LESSONS FROM THE ANALOG ERA. Within the language archiving community we now face the problem of how to preserve and access a continually growing body of born-digital documentation of endangered languages. But at the Alaska Native Language Archive (ANLA, http://www.uaf.edu/anla) we have always been playing catch-up in the digital realm. -

Cultural Anthropology: Basic Schools and Branches

А 95AL-FARABI KAZAKH NATIONAL UNIVERSITY A. Zholdybayeva Zh. Doskhozhina CULTURAL ANTHROPOLOGY: BASIC SCHOOLS AND BRANCHES Teaching manual Almaty «Qazaq University» 2020 UDC 902/904 (075.8) LBC 63.4я73 Zh 50 Recommended for publication by the decision of the Academic Council of the Faculty of Philosophy and Political Science and Publishing Council of al-Farabi KazNU (Protocol No.1 dated 10.09.2020) Reviewers: Doctor of Philosophical science, Professor A.K. Abisheva PhD D.M. Zhanabayeva PhD A.M. Kadyralieva Zholdybayeva A. Zh 50 Cultural Anthropology: Basic Schools and Branches: teaching manual / A. Zholdybayeva, Zh. Doskhozhina. – Almaty: Qazaq University, 2020. – 122 p. ISBN 978-601-04-4880-3 This manual has been developed in accordance with the requirements of the new State educational standard for higher vocational education in the Republic of Kazakhstan. It reflects the modern state of cultural anthropology and is intended for university students. The authors of the manual tried to present the material as interestingly as possible, both in a substantive and in a methodical way. In its chapters, paragraphs are singled out, “photo frames” and font underlined will make it easier to find the necessary material, specific data, facts, original concepts and formulations, logical conclusions and assessments. The authors hope that it will be accepted by the students and will help them enter more deeply the world of culture, which is our “second nature”, a diverse, creative, intel- lectual and active form of life. UDC 902/904 (075.8) LBC 63.4я73 ISBN 978-601-04-4880-3 © Zholdybayeva A., Doskhozhina Zh., 2020 © Al-Farabi KazNU, 2020 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION .......................................................................................... -

PDF Download Intercultural Communication for Global

INTERCULTURAL COMMUNICATION FOR GLOBAL ENGAGEMENT 1ST EDITION PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Regina Williams Davis | 9781465277664 | | | | | Intercultural Communication for Global Engagement 1st edition PDF Book Resilience, on the other hand, includes having an internal locus of control, persistence, tolerance for ambiguity, and resourcefulness. This textbook is suitable for the following courses: Communication and Intercultural Communication. Along with these attributes, verbal communication is also accompanied with non-verbal cues. Create lists, bibliographies and reviews: or. Linked Data More info about Linked Data. A critical analysis of intercultural communication in engineering education". Cross-cultural business communication is very helpful in building cultural intelligence through coaching and training in cross-cultural communication management and facilitation, cross-cultural negotiation, multicultural conflict resolution, customer service, business and organizational communication. September Lewis Value personal and cultural. Inquiry, as the first step of the Intercultural Praxis Model, is an overall interest in learning about and understanding individuals with different cultural backgrounds and world- views, while challenging one's own perceptions. Need assistance in supplementing your quizzes and tests? However, when the receiver of the message is a person from a different culture, the receiver uses information from his or her culture to interpret the message. Acculturation Cultural appropriation Cultural area Cultural artifact Cultural -

[.35 **Natural Language Processing Class Here Computational Linguistics See Manual at 006.35 Vs

006 006 006 DeweyiDecimaliClassification006 006 [.35 **Natural language processing Class here computational linguistics See Manual at 006.35 vs. 410.285 *Use notation 019 from Table 1 as modified at 004.019 400 DeweyiDecimaliClassification 400 400 DeweyiDecimali400Classification Language 400 [400 [400 *‡Language Class here interdisciplinary works on language and literature For literature, see 800; for rhetoric, see 808. For the language of a specific discipline or subject, see the discipline or subject, plus notation 014 from Table 1, e.g., language of science 501.4 (Option A: To give local emphasis or a shorter number to a specific language, class in 410, where full instructions appear (Option B: To give local emphasis or a shorter number to a specific language, place before 420 through use of a letter or other symbol. Full instructions appear under 420–490) 400 DeweyiDecimali400Classification Language 400 SUMMARY [401–409 Standard subdivisions and bilingualism [410 Linguistics [420 English and Old English (Anglo-Saxon) [430 German and related languages [440 French and related Romance languages [450 Italian, Dalmatian, Romanian, Rhaetian, Sardinian, Corsican [460 Spanish, Portuguese, Galician [470 Latin and related Italic languages [480 Classical Greek and related Hellenic languages [490 Other languages 401 DeweyiDecimali401Classification Language 401 [401 *‡Philosophy and theory See Manual at 401 vs. 121.68, 149.94, 410.1 401 DeweyiDecimali401Classification Language 401 [.3 *‡International languages Class here universal languages; general -

Newsletter Spring 2019

C/TFN NEEK WATSÍX Issue 16 11 Neek Watsíx Spring 2019 The Maasai delegation from North Tanzania visiting C/TFN Traditional Territory IN THIS ISSUE Message from Deputy Haa Shaa du Hen by Daphne Pelletier Vernier Since Maria's arrival in the Deputy Haa Shaa du Hen position in February, she has been extremely busy assuring the continuation of different initiatives, priorities and projects. She met with different Ministers in less than 4 months on important topics such as; Meeting with Minister Frost (YG/Env) along with Frank James and Chief Smith from CAFN on the Kusawa Park, met with Minister Streicker (YG/Comm. Serv.) along with Executive Council (EC) representatives on economic development, met with Minister Mostyn (YG/Hwys & Public Works) with Frank James on the use of the airport runway during the Haa Kusteeyi Celebration, met with Minister Bennett (Canada/Crown-Indigenous Relations) and Minister O’Regan (Canada/Indigenous Services) on the Financial Transfer Agreement (FTA) and the Health and Wellness of our Children and Citizens. She also met with Deputy Minister Paul C/TFN Comprehensive Community Moore (YG/EMR) and Director of Implementation Ross Pattee from Ottawa. Plan - Fire Feast She had the chance to attend a Dahk-Ka meeting in March with Nha Shade Heni Sidney and The comprehensive community planning Spokesperson Ward in Whitehorse. They are currently looking at an eventual possibility to orchestrated by Gunta Business hosted a fire open a Dahk-Ka office and will be looking at hiring a Coordinator. Some EC Feast for the community on May 22nd 2019. Representatives, the Governance Manager James Baker and Maria attended a Teslin Tlingit Page 6 Council General Council in April and it was very good. -

Tagish Stories by Angela Sidney

TAGISH STORIES By Mrs. Angela Sidney recorded by Julie Cruikshank drawings by Susan McCallum TAGISH STORIES By Mrs. Angela Sidney recorded by Julie Cruikshank drawings by Susan McOallum @ Mrs. Angela Sidney Not to be reproduced without permission from Mrs. Sidney Published by the Council for Yukon Indians and the Government of Yukon Cover photo of Angela Sidney by Andrew Hume Whitehorse, Yukon 1982 COÌ{TEIVTS Page Introduction Crow Stories: Ch'eshk'ia Kwándech 1 How People Got Flint I7 The Flood T9 The Old Woman Under the World 20 Eclipse. 20 How Animals Broke Through the Sky .... 2l Story of the Great Snake, Gçç Cho. 23 Go¿ þasók or Hushkét Ghugha .... 29 The Woman Stolen by Lynx 33 Southwind Story 37 The Stolen Woman 40 The Stolen Woman 43 Killer Whale. 45 The Girl Eaten by TÞhcha 51 Wolf Helper 55 Fox Helper.... 58 Land Otter Story, Kóoshdaa Kóa . 60 Land Otter Story. 65 Land Otter Story. 67 Witch Story. 70 Witch Story. 73 Witch Story. 75 The Man Who Died and Took His Brother 76 Beaver and Porcupine . 80 Skookum Jim's Frog Helper. 81 Falling Through a Glacier 88 Notes. 90 I ntroduction and Aclcnowledgements : This is the second booklet of stories narrated by Mrs. Angela Sidney at Tägish in the southern Yukon. During the four years between 1975 and 1979, Mrs. Sidney recorded a family history for her own immediate family, and a number of stories which she wanted published for a wider audience, particularly for young people. ln 1977, some of her stories were published by the Council for Yukon Indians ínMy Stories are My Wealth together with stories by Mrs.