Tocc0284notes.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

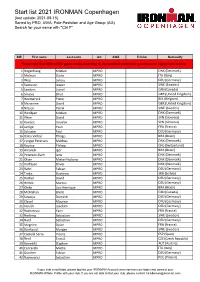

Start List 2021 IRONMAN Copenhagen (Last Update: 2021-08-15) Sorted by PRO, AWA, Pole Posistion and Age Group (AG) Search for Your Name with "Ctrl F"

Start list 2021 IRONMAN Copenhagen (last update: 2021-08-15) Sorted by PRO, AWA, Pole Posistion and Age Group (AG) Search for your name with "Ctrl F" BIB First name Last name AG AWA TriClub Nationallty Please note that BIBs will be given onsite according to the selected swim time you choose in registration oniste. 1 Hogenhaug Kristian MPRO DNK (Denmark) 2 Molinari Giulio MPRO ITA (Italy) 3 Wojt Lukasz MPRO DEU (Germany) 4 Svensson Jesper MPRO SWE (Sweden) 5 Sanders Lionel MPRO CAN (Canada) 6 Smales Elliot MPRO GBR (United Kingdom) 7 Heemeryck Pieter MPRO BEL (Belgium) 8 Mcnamee David MPRO GBR (United Kingdom) 9 Nilsson Patrik MPRO SWE (Sweden) 10 Hindkjær Kristian MPRO DNK (Denmark) 11 Plese David MPRO SVN (Slovenia) 12 Kovacic Jaroslav MPRO SVN (Slovenia) 14 Jarrige Yvan MPRO FRA (France) 15 Schuster Paul MPRO DEU (Germany) 16 Dário Vinhal Thiago MPRO BRA (Brazil) 17 Lyngsø Petersen Mathias MPRO DNK (Denmark) 18 Koutny Philipp MPRO CHE (Switzerland) 19 Amorelli Igor MPRO BRA (Brazil) 20 Petersen-Bach Jens MPRO DNK (Denmark) 21 Olsen Mikkel Hojborg MPRO DNK (Denmark) 22 Korfitsen Oliver MPRO DNK (Denmark) 23 Rahn Fabian MPRO DEU (Germany) 24 Trakic Strahinja MPRO SRB (Serbia) 25 Rother David MPRO DEU (Germany) 26 Herbst Marcus MPRO DEU (Germany) 27 Ohde Luis Henrique MPRO BRA (Brazil) 28 McMahon Brent MPRO CAN (Canada) 29 Sowieja Dominik MPRO DEU (Germany) 30 Clavel Maurice MPRO DEU (Germany) 31 Krauth Joachim MPRO DEU (Germany) 32 Rocheteau Yann MPRO FRA (France) 33 Norberg Sebastian MPRO SWE (Sweden) 34 Neef Sebastian MPRO DEU (Germany) 35 Magnien Dylan MPRO FRA (France) 36 Björkqvist Morgan MPRO SWE (Sweden) 37 Castellà Serra Vicenç MPRO ESP (Spain) 38 Řenč Tomáš MPRO CZE (Czech Republic) 39 Benedikt Stephen MPRO AUT (Austria) 40 Ceccarelli Mattia MPRO ITA (Italy) 41 Günther Fabian MPRO DEU (Germany) 42 Najmowicz Sebastian MPRO POL (Poland) If your club is not listed, please log into your IRONMAN Account (www.ironman.com/login) and connect your IRONMAN Athlete Profile with your club. -

Legacy Image

5-(948-~gblb SOWARE ENGINEERING LABORATORY SERIES SEL-95-004 PROCEEDINGS OF THE TWENTIETH ANNUAL SOFTWARE ENGINEERING WORKSHOP DECEMBER 1995 National Aeronautics and Space Administration Goddard Space Flight Center Greenbelt, Maryland 20771 Proceedings of the Twentieth Annual Software Engineering Workshop November 29-30,1995 GODDARD SPACE FLIGHT CENTER Greenbelt, Maryland The Software Engineering Laboratory (SEL) is an organization sponsored by the National Aeronautics and Space AdministratiodGoddard Space Flight Center (NASAIGSFC) and created to investigate the effectiveness of software engineering technologies when applied to the development of applications software. The SEL was created in 1976 and has three primary organizational members: NASAIGSFC, Software Engineering Branch The University of Maryland, Department of Computer Science .I Computer Sciences Corporation, Software Engineering Operation The goals of the SEL are (1) to understand the software development process in the GSFC environment; (2) to measure the effects of various methodologies, tools, and models on this process; and (3) to identifjr and then to apply successful development practices. The activities, findings, and recommendations of the SEL are recorded in the Software Engineering Laboratory Series, a continuing series of reports that includes this document. Documents from the Software Engineering Laboratory Series can be obtained via the SEL homepage at: or by writing to: Software Engineering Branch Code 552 Goddard Space Flight Center Greenbelt, Maryland 2077 1 SEW Proceedings iii The views and findings expressed herein are those of, the authors and presenters and do not necessarily represent the views, estimates, or policies of the SEL. All material herein is reprinted as submitted by authors and presenters, who are solely responsible for compliance with any relevant copyright, patent, or other proprietary restrictions. -

Carnegie Hall Rental

Friday Evening, October 26, 2012, at 8:00 Isaac Stern Auditorium/Ronald O. Perelman Stage Conductor’s Notes Q&A with Leon Botstein at 7:00 presents 50th Birthday Celebration LEON BOTSTEIN, Conductor JOHN STAFFORD SMITH The Star-Spangled Banner Arr. by LEOPOLD STOKOWSKI CHARLES IVES Symphony No. 4 Prelude: Maestoso Allegretto Fugue: Andante moderato Largo maestoso BLAIR MCMILLEN, Piano THE COLLEGIATE CHORALE Intermission GUSTAV MAHLER Symphony No. 8 in E-flat Major (“Symphony of a Thousand”) Part 1: Hymnus: Veni, Creator Spiritus Part 2: Final scene from Goethe’s Faust Part 2 Magna Peccatrix: REBECCA DAVIS, Soprano Una Poenitentium: ABBIE FURMANSKY, Soprano Mater Gloriosa: KATHERINE WHYTE, Soprano Mulier Samaritana: SUSAN PLATTS, Mezzo-soprano Maria Aegyptiaca: FREDRIKA BRILLEMBOURG, Mezzo-soprano (continued) This evening’s concerT will run approximaTely Two and a half hours, inlcuding one 20-minuTe inTermission. The Empire State Building is liT red and white this evening in honor of American Symphony Orchestra’s 50th Birthday. We would like to Thank the Empire State Building for This special honor. American Symphony Orchestra welcomes students and teachers from ASO’s arts education program, Music Notes. For information on how you can support Music Notes, visit AmericanSymphony.org. PLEASE SWITCH OFF YOUR CELL PHONES AND OTHER ELECTRONIC DEVICES. Dr. Marianus: CLAY HILLEY, Tenor Pater EcsTaticus: TYLER DUNCAN, Baritone Pater Profundus: DENIS SEDOV, Bass THE COLLEGIATE CHORALE JAMES BAGWELL, Director THE BROOKLYN YOUTH CHORUS DIANNE BERKUN, Director THE Program JOHN STAFFORD SMITH (Arr. by LEOPOLD STOKOWSKI) The Star-Spangled Banner Smith: Born March 30, 1750 in Gloucester, England Died September 21, 1836 in London Stokowski: Born April 18, 1882 in London Died September 13, 1977 in Nether Wallop, Hampshire, England Composed by Smith as “The Anacreontic Song” in 1775 in London Stokowski first arranged the song in 1940. -

The Berkeley Rep Magazine 2017–18 · Issues 5–6

aids in the United States today 25 · 4 questions for the cast 27 · The program for Angels in America: A Gay Fantasia on National Themes 33 THE BERKELEY REP MAGAZINE 2017–18 · ISSUES 5–6 AG_program.indd 1 4/4/18 3:54 PM Encore spread.indd 1 2/28/18 3:55 PM Encore spread.indd 1 2/28/18 3:55 PM AG_program.indd 4 4/4/18 3:54 PM IN THIS ISSUE 16 23 29 BERKELEY REP PRESENTS MEET THE CAST & CREW · 34 ANGELS IN AMERICA: A GAY FANTASIA ON NATIONAL THEMES · 33 PROLOGUE A letter from the artistic director · 7 Connect with us online! A letter from the managing director · 8 Visit our website berkeleyrep.org facebook.com/ @berkeleyrep You can buy tickets and plan your visit, berkeleyrep watch videos, sign up for classes, donate to vimeo.com/ @berkeleyrep REPORTS the Theatre, and explore Berkeley Rep. berkeleyrep The Messenger has arrived: berkeleyrep. berkeleyrep The art of theatrical flying ·13 We’re mobile! tumblr.com Crossing paths: Download our free iPhone or Google Play app —or visit our mobile site —to buy tickets, read An intergenerational conversation · 16 the buzz, watch videos, and plan your visit. June 2018, when 21 Ground Floor projects roam · 19 Considerations FEATURES Only beverages in cans, cartons, or cups with You are welcome to take a closer look, but The Origin Story · 20 lids are allowed in the house. Food is prohibited please don’t step onto the stage or touch in the house. the props. Tinkering and tinkering: An interview with Tony Kushner and Tony Taccone · 21 Smoking and the use of e-cigarettes is prohibited Any child who can quietly sit in their own by law on Berkeley Rep’s property. -

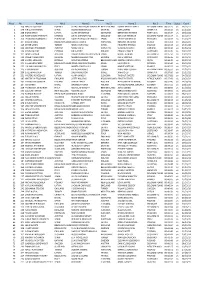

Place No Name 1 Nat 1 Name 2 Nat 2 Name 3 Nat 3

FTE-Junior Place No Name 1 Nat 1 Name 2 Nat 2 Name 3 Nat 3 Time Status Count 1 158 MACIEJ LUCERSKI POLAND SEBASTIAN AYSON MACARLANENEW ZEALAND ESMEE VAN DE MAELE BELGIUM FLANDERS00:31:23 ok 24/21/17 2 240 KIRILL PIVOVAROV SPAIN OLEKSII KONOVALOV UKRAINE MAN ZHANG CHINA P.R. 00:33:10 ok 21/19/22 3 238 SIGNE SIRMA LATVIA CLARE STANSFIELD SCOTLAND BERNARDO PEREIRA PORTUGAL 00:33:47 ok 19/22/24 4 260 TOMI-ANDRE PIIRMETS ESTONIA ANIKA CHINTAPATLA ENGLAND BEN VAN HEMELEN BELGIUM FLANDERS00:34:19 ok 24/22/17 5 200 LEONARDO RAMALHO PORTUGAL DAVID POBLACIÓN CRIADO SPAIN CECILIE ANDERSON ENGLAND 00:34:59 ok 21/20/21 6 197 SIEL DE SMUL BELGIUM FLANDERSVASCO DUARTE PORTUGAL RIHARDS KRUMINS LATVIA 00:35:01 ok 18/21/23 7 119 SEHER ŞAHİN TURKEY REGEV AVRAHAM ISRAEL FRYDERYK PRYJMA POLAND 00:35:18 ok 15/19/28 8 232 JOHANNA TRUMMER AUSTRIA MINGHAO LI CHINA P.R. VLADYSLAV LIAKH UKRAINE 00:35:30 ok 24/19/19 9 234 KEVIN HALLOP ESTONIA JULIA SEIDEL POLAND EWAN SHEARER SCOTLAND 00:35:35 ok 20/22/20 10 121 JANNIS BONEK AUSTRIA INMACULADA CRESPO GONZÁLEZSPAIN BORILE ADRIAN BELGIUM FC 00:35:50 ok 19/21/23 11 213 VALERIY SHELUDKO UKRAINE MARKUS-HARALD PAIS ESTONIA KATIE SKINNER SCOTLAND 00:36:36 ok 23/21/19 12 209 KAAREL VESILIND ESTONIA WOUT KEUPPENS BELGIUM FLANDERSANDREA GRÁCIA JÁTIVA SPAIN 00:36:40 ok 22/22/19 13 271 KLAAS MELLEBEEK BELGIUM FLANDERSIRENE GARCÍA BERNABEU SPAIN LAURI PÄHN ESTONIA 00:36:46 ok 20/20/22 14 222 LUCIANO MASSACCESI ITALY MARTA LÓPEZ GUILL SPAIN MARIE VUITTON FRANCE 00:36:51 ok 17/20/25 15 115 FLORIAN KURZ AUSTRIA AYLİN ŞENGÜNLÜ TURKEY DRIES VAN LOMMEL BELGIUM FLANDERS00:36:53 ok 22/18/22 16 206 SÜLEYMAN EREN TURKEY DALIT MANSOOR ISRAEL XINHAO LU CHINA P.R. -

2013 2013 5Th International Conference on Cyber Conflict

2013 2013 5th International Conference on Cyber Conflict PROCEEDINGS K. Podins, J. Stinissen, M. Maybaum (Eds.) 4-7 JUNE 2013, TALLINN, ESTONIA 2013 5TH INTERNATIONAL CONFERENCE ON CYBER CONFLICT (CYCON 2013) Copyright © 2013 by NATO CCD COE Publications. All rights reserved. IEEE Catalog Number: CFP1326N-PRT ISBN 13 (print): 978-9949-9211-4-0 ISBN 13 (pdf): 978-9949-9211-5-7 ISBN 13 (epub): 978-9949-9211-6-4 Copyright and Reprint Permissions No part of this publication may be reprinted, reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the NATO Cooperative Cyber Defence Centre of Excellence ([email protected]). This restriction does not apply to making digital or hard copies of this publication for internal use within NATO, and for personal or educational use when for non-profit or non- commercial purposes, providing that copies bear this notice and a full citation on the first page as follows: [Article author(s)], [full article title] 2013 5th International Conference on Cyber Conflict K. Podins, J. Stinissen, M. Maybaum (Eds.) 2013 © NATO CCD COE Publications Printed copies of this publication are available from: NATO CCD COE Publications Filtri tee 12, 10132 Tallinn, Estonia Phone: +372 717 6800 Fax: +372 717 6308 E-mail: [email protected] Web: www.ccdcoe.org Layout: Marko Söönurm Legal Notice: This publication contains opinions of the respective authors only. They do not necessarily reflect the policy or the opinion of NATO CCD COE, NATO, or any agency or any government. -

Õþl6s£Ñ &Åaà Łáë[5Ù—H

557595bk Hummel US 13/6/05 4:20 pm Page 4 Conservatory Special Lyceum and St Petersburg Conservatory with Marina Volf. At the age of nine she performed in one evening’s programme Schumann’s Piano Concerto and Beethoven’s Emperor Concerto, a feat still unprecedented for a child of that age and recognised as a milestone in the history of piano performances. Two years later she performed HUMMEL Mozart’s Piano Concerto No. 24 in Moscow Conservatory’s Great Hall with the Moscow Chamber Orchestra. Polina Osetinskaya attracted major television companies which filmed documentaries of her with two live televised appearances in the United States and Russia in 1985 and 1986, seen by millions on both sides of the Atlantic. At the Violin Concerto ages of eighteen and nineteen she completed two Japanese concert tours, also performing Tchaikovsky’s Concerto No. 1 with the Tokyo Philharmonic. She has appeared as a soloist with the world’s most prestigious orchestras, and in 2002 was a Triumph Award recipient for her outstanding contribution to Russian culture. Her international career brings a Piano and Violin Concerto large repertoire including the most complicated solo, chamber and orchestral programmes, from the early Baroque to the contemporary. She has recorded with the Naxos, Sony, and Bel Air labels. Alexander Trostiansky, Violin • Polina Osetinskaya, Piano Russian Philharmonic Orchestra The Russian Philharmonic Orchestra is firmly rooted in Russia’s rich musical traditions, and has achieved an Russian Philharmonic Orchestra impressive and outstanding musical quality by drawing its musicians from the highest ranks of Russia’s most famous orchestras such as the Moscow Radio Symphony Orchestra, the Russian National Orchestra and the State Symphony Gregory Rose Orchestra.The Russian Philharmonic Orchestra was originally formed as a recording ensemble and has gone on to receive high acclaim also for its concert performances. -

Globe. Athletic Gear for Firefighters.Tm

PERFORMANCE AND PROTECTION IN PERFECT BALANCE. GLOBE. ATHLETIC GEAR FOR FIREFIGHTERS.TM Globe gear is designed to meet the new challenges you face every day to help keep you safe and healthy throughout your career and beyond. Get the full story at MSAfire.com/Globe GLOBE, ATHLETIX, and designs are trademarks or registered trademarks of Globe Holding Company, LLC. DUPONT, KEVLAR, NOMEX, and designs are trademarks or registered trademarks of E.I. DuPont de Nemours and Company or its affiliates. Spring 2019 Fire Fighter Quarterly vol. 102 no.2 33 Mount Pleasant Local 4693 Fights for Increased Staffing Truro Local 1627 Member Skyler Blackie 18 2019 Legislative Conference 34 Mourned Cover Features Departments 12 The Power of 16 IAFF Endorses Joe Biden for President n 5 From the General President Political Action Based on his unequaled record of Affiliates across the support on fire fighter issues, the IAFF n 7 From the General International are winning Executive Board voted unanimously to Secretary-Treasurer state and local support Biden in the Democratic primary. n 9 Letters legislative victories following the IAFF 18 Building On Our Legislative Success n 10 Noteworthy News political action playbook. IAFF legislative conferences provide opportunities to advocate on priority n 22 Across the IAFF On the cover: Montana Governor Steve legislation and solidify support for fire Bullock signs legislation giving fire fighter issues. n 33 Local Scene fighters presumptive protections. n 35 On the Road n 36 Retirees n 44 Never Forget n 46 Last Alarm Download the IAFF App The IAFF app is available for Apple and Android devices. -

Partners Help Fulfill Bju's Mission

PARTNERS HELP FULFILL BJU’S MISSION Rev. and Mrs. Stacey B. Peek Rev. and Mrs. Rex K. Clemens Mrs. Susan L. Jacox Mr. and Mrs. Edward E. Sedivy Dr. and Mrs. Stephen D. Pettit Miss Martha L. Cochran Mr. and Mrs. Bobby J. Johnson Mr. and Mrs. John E. Sedivy Bob Jones University recognizes and thanks the following alumni and friends whose generous gifts since June 1, 2015, Dr. and Mrs. Warren L. Popwell Mr. and Mrs. Michael G. Collins Mr. and Mrs. Jeffrey A. Johnson Dr. Lesa M. Seibert Mr. and Mrs. Marvin P. Reem Mr. Clarence E. Cook Mr. and Mrs. Kenneth E. Johnson Mr. and Mrs. Stephen R. Sejda demonstrate their partnership in helping BJU fulfill its mission. Mr. and Mrs. Donald R. Rochester Mr. and Mrs. Russell I. Cooper Mr. and Mrs. Michael D. Johnson Mr. and Mrs. David W. Simonaire Mr. and Mrs. Timothy J. Rogne Mrs. Virginia C. Copiaco Mr. and Mrs. Stephen E. Johnston Miss Jonna M. Smith Mr. and Mrs. Brian P. Romig Mr. and Mrs. Wesley F. Curtis Mr. and Mrs. Timothy J. Joiner Mr. Ralph V. Starr $25,000+ $5,000 to $9,999 $2,500 to $4,999 Mr. and Mrs. Timothy L. Stees Mr. and Mrs. Michael B. Cushman Mr. and Mrs. William W. Kayser Ms. Vickie B. Stone Dr. and Mrs. T. W. Brashier Sr. LtCol. and Mrs. J A. Abels Mrs. Jane Allen Dr. and Mrs. Robert R. Taylor Jr. Mr. Parke M. Dague Dr. and Mrs. Leonard C. Keifer Rev. and Mrs. Melvin L. Stonewall Dr. -

2014 Drake Relays

Complete Results 2014 DRAKE RELAYS | APRIL 23-27 | DRAKE STADIUM Drake Stadium - Site License Hy-Tek's MEET MANAGER Page 1 2014 Drake Relays presented by Hy-Vee America's Athletic Classic Drake University, Des Moines, Iowa - 4/23/2014 to 4/26/2014 Results 5 Daniel Bonthius JR Wartburg 1:53.03 Event 5 Men 100 Meter Dash Univ/Col 6 Jake Mazanke SO Loyola IL 1:53.70 Stadium: 9.89 S 6/10/2011 Ngonidzashe Makusha 7 Moses Heppner SR North Dakota 1:53.89 Relays: 10.11 D 1983 Calvin Smith 8 Ryan Van Portfliet JR Loyola IL 1:54.02 Name Yr School Prelims 9 Kisean Smith SO Georgia 1:54.13 Preliminaries 10 Chris Miedema SR DePaul 1:54.49 1 Trayvon Bromell FR Baylor 10.16Q2.0 11 Justin Chambers SR Texas Christ 1:55.21 2 Ronnie Baker SO Texas Christ 10.29Q1.0 12 Goaner Deng SO Minnesota 1:56.10 3 Johnathan Smith SR Georgia 10.38Q-0.6 4 O'Shea Wilson FR Iowa 10.48Q0.6 Event 12 Men 800 Meter Run Unseeded Univ/Col 5 Wayne Gordon SO Kent St 10.36q 1.0 Stadium: 1:44.71 S 6/10/2011 Robby Andrews 6 Johnathan Farquarshon JR Abilene Chr 10.44q 2.0 Relays: 1:50.37 D 4/26/2012 Lucas Manring 7 Thurgood Dennis JR UW-Eau Clair 10.48q -0.6 Name Yr School Finals 8 Everett Walker SR Baylor 10.51q -0.6 Finals 9 Jerrell Hancock SR Minn St Mankato 10.51 2.0 1 McKena Ramos FR UW-Oshkosh 1:51.33 10 Kolby Listenbee FR Texas Christ 10.52 0.6 2 Bradley Johnson FR Minnesota 1:52.13 11 Tevin-Cee Mincy SR Iowa 10.55 1.0 3 Jermaine Blake SR Lincoln (MO) 1:53.12 12 Corneil Lionel SO Iowa Western 10.55 1.0 4 Jeffrey Cottrell JR Minnesota 1:53.24 13 Tim Thompson SR Nebraska 10.56 -

Estonian: Typological Studies V

TARTU ÜLIKOOLI EESTI KEELE ÕPPETOOLI TOIMETISED 18 PUBLICATIONS OF THE DEPARTMENT OF ESTONIAN OF THE UNIVERSITY OF TARTU 18 ESTONIAN: TYPOLOGICAL STUDIES V edited by Mati Erelt TARTU 2001 ESTONIAN: TYPOLOGICAL STUDIES V TARTU ÜLIKOOLI EESTI KEELE ÕPPETOOLI TOIMETISED 18 PUBLICATIONS OF THE DEPARTMENT OF ESTONIAN OF THE UNIVERSITY OF TARTU 18 ESTONIAN: TYPOLOGICAL STUDIES V edited by Mati Erelt TARTU 2001 ESTONIAN: TYPOLOGICAL STUDIES V This work was supported by the Estonian Science Foundation, Grant No. 3259. Raamatukogu © University of Tartu, 2001 ISSN 1406-0183 Tartu Ülikooli Kirjastuse trükikoda Tiigi 78, Tartu 50410 Tellimus nr 651 CONTENTS Mati Erelt Some notes on the grammaticalization of the verb pidama in Estonian ......................................................7 Külli Habicht Lexicalization and grammaticalization - opposite phenomena? About some lexicalized verb forms of Old Written Estonian ....26 Reet Kasik Analytic causatives in Estonian..................... ................................77 Ago Kiinnap On some peculiarities of the Estonian language ....................... 123 Liina Lindström Verb-initial clauses in the narrative ............................................ 138 Merilin Mil] an Adjectival modification in Estonian and Estonian sign language ................................... 169 Enn Veldi Estonian and English: a lexicographer’s view. II 189 SOME NOTES ON THE GRAMMATICALIZATION OF THE VERB pidama IN ESTONIAN Mati Erelt University of Tartu 1. Two pidama-\erbs The Explanatory Dictionary of Estonian (EKS) tells us that there are two pidama-verbs in contemporary Estonian. One of them occurs mostly in the meanings ‘keep, hold, regard, etc.’, e.g. (1) Ta suudab veel mõõka käes pidada. ‘He can still hold the sword in his hand’. Kurjategijat peeti üksikkambris. ‘The criminal was kept in solitary confinement’. Ta ei suutnud naeru tagasi pidada. -

News 2011/12 Boosey & Hawkes · Schott Music Autumn · Winter

News 2011/12 Boosey & Hawkes · Schott Music Autumn · Winter The Solo Piano Collection The Boosey & Hawkes Solo Piano Collection provides the intermediate pianist with exciting repertoire in accessible yet authentic arrangements. Russian Masters Classical Chill-Out 20 Russian classics arranged for 20 relaxing melodies to soothe the intermediate pianist, your soul arranged for the including pieces by 20th-century intermediate pianist, featuring masters Prokofieff, Rachmaninoff all-time favourite repertoire and Shostakovich, alongside along side little-known 19th-century greats Borodin, classical gems. Mussorgsky and Tchaikovsky. ISMN 979-0-060-12389-4 ISMN 979-0-060-12387-0 BH 12389 · in prep. BH 12387 · in prep. Rachmaninoff Best Of British Russian great Sergei Great Britain’s finest 20th - and Rachmaninoff’s most celebrated 21st – century composers are orchestral and choral themes represented in this splendid arranged for the intermediate collection of arrangements for pianist. the intermediate pianist, from ISMN 979-0-060-12390-0 Elgar and Holst to Karl Jenkins BH 12390 · in prep. via Bridge, Britten and Bliss. ISMN 979-0-060-12388-7 BH 12388 · in prep. In preparation for 2012: American Greats Shostakovich BH 12392 · ISMN 979-0-060-12392-4 BH 12395 · ISMN 979-0-060-12395-5 Prokofieff Tango BH 12394 · ISMN 979-0-060-12394-8 BH 12391 · ISMN 979-0-060-12391-7 Boosey & Hawkes is exclusively distributed by Schott Music. MA 5525-01 · 08/11 · 5525-01 MA www.schott-music.com www.boosey.com Dr. Peter Hanser-Strecker Publisher Along with our international partner publishers Boosey & Hawkes and Belaieff, we would like to give you a preview of our interesting selection of music in a variety of styles and levels, from material for beginners through to advanced performance repertoire.