SCCR/8/6 ORIGINAL: Spanish WIPO DATE: October 15, 2002 WORLD INTELLECTUAL PROPERTY ORGANIZATION GENEVA

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Grilla De Horarios De Estudio Urbano

GRILLA DE HORARIOS DE ESTUDIO URBANO LUNES 18 a 20 hs. - CURSO BÁSICO DE PROTOOLS | Francisco Rojas | 5 de mayo 18 a 20 hs. - EDICIÓN INDEPENDIENTE DE DISCOS | Fabio Suárez | 19 de mayo 19 a 21 hs. - CIRCULACIÓN DE MÚSICA POR LA WEB | Matías Erroz | 19 de mayo 19 a 21 hs. - CANTO EN EL ROCK | María Rosa Yorio | 5 de mayo 20 a 22 hs. - ARTE Y TECNOLOGÍA MULTIMEDIA | Alejandra Isler | 19 de mayo MARTES 19 a 21 hs. - INTRO A DJ | Carlos Ruiz y Ramón Gallo (Adisc) | 6 de mayo 19 a 21 hs. - ARTE DE TAPA DE DISCOS | Ezequiel Black | 29 de abril 19 a 21 hs. - VIAJE POR LA MENTE DE LOS GENIOS DEL ROCK | Pipo Lernoud | 29 de abril 19 a 21 hs. - ARREGLOS Y COMPOSICIÓN EN LA MÚSICA POPULAR | Pollo Raffo | comienza en junio, al finalizar el ciclo de Pipo Lernoud MIÉRCOLES 17 a 19 hs. - TALLER LITERARIO | Ariel Bermani | 30 de abril 17 a 19 hs. - TALLER DE GRABACIÓN | Mariano Ondarts | 30 de abril 18 a 20 hs. - PERIODISMO Y ROCK | Matías Capelli | 7 de mayo 19 a 21 hs. - ABLETON LIVE | Eduardo Sormani | 30 de abril 19 a 21 hs. - REASON | Eduardo Sormani | comienza en junio, al finalizar el curso de Ableton Live 19 a 21 hs. - COMUNICACIÓN Y MANAGEMENT DE PROYECTOS MUSICALES | Leandro Frías | 30 de abril JUEVES 17 a 19 hs. - SONIDO EN VIVO | Pablo González Martínez | 8 de mayo 17:30 a 19:30 hs. - LA CÁMARA POR ASALTO | Pablo Klappenbach | 8 de mayo 19 a 21 hs. - REVOLUCIÓN DEL ROCK | Alfredo Rosso | 8 de mayo 19:30 a 21:30 hs. -

Escúchame, Alúmbrame. Apuntes Sobre El Canon De “La Música Joven”

ISSN Escúchame, alúmbrame. 0329-2142 Apuntes de Apuntes sobre el canon de “la investigación del CECYP música joven” argentina entre 2015. Año XVII. 1966 y 1973 Nº 25. pp. 11-25. Recibido: 20/03/2015. Aceptado: 5/05/2015. Sergio Pujol* Tema central: Rock I. No caben dudas de que estamos viviendo un tiempo de fuerte interroga- ción sobre el pasado de lo que alguna vez se llamó “la música joven ar- gentina”. Esa música ya no es joven si, apelando a la metáfora biológica y más allá de las edades de sus oyentes, la pensamos como género desarro- llado en el tiempo según etapas de crecimiento y maduración autónomas. Veámoslo de esta manera: entre el primer éxito de Los Gatos y el segundo CD de Acorazado Potemkin ha transcurrido la misma cantidad de años que la que separa la grabación de “Mi noche triste” por Carlos Gardel y el debut del quinteto de Astor Piazzolla. ¿Es mucho, no? En 2013 la revista Rolling Stone edición argentina dedicó un número es- pecial –no fue el primero– a los 100 mejores discos del rock nacional, en un arco que iba de 1967 a 2009. Entre los primeros 20 seleccionados, 9 fueron grabados antes de 1983, el año del regreso de la democracia. Esto revela que, en el imaginario de la cultura rock, el núcleo duro de su obra apuntes precede la época de mayor crecimiento comercial. Esto afirmaría la idea CECYP de una época heroica y proactiva, expurgada de intereses económicos e ideológicamente sostenida en el anticonformismo de la contracultura es- tadounidense adaptada al contexto argentino. -

Charly García

Charly García ‘El Prócer Oculto’ [Un relato a través de entrevistas a Sergio Marchi y Alfredo Rosso] Alumna: Laura Impellizzeri ‘Charly García: El Prócer Oculto’ Comunicación Social - UNLP 2017 Directora: Prof. Mónica Caballero Agradecimientos. La última etapa de la carrera es la elaboración del T.I.F. [Trabajo Integrador Final] que lleva tiempo, dedicación, ganas y esfuerzo. Por supuesto que estos elementos no confluyen siempre; no están de forma permanente ni simultánea. En esos ‘lapsus’ de cansancio, de tener la mente en blanco porque no hay ideas que plasmar, aparecen los estímulos, las ayudas extra-académicas que nos dan el aliento necesario para seguir adelante. En mi caso, necesito agradecer profundamente a los dos pilares de mi vida que son mi madre Julia y mi padre Miguel, quienes, además de darme educación y amor desde que nací, me han dado la seguridad, la confianza y el apoyo incondicional en cada paso que di y doy en mi carrera. También agradezco a mi hermana Marta por haberme acercado, de alguna forma, a Charly García. No pueden faltar mis amigos. Estuvieron ahí ante las permanentes caídas y el enojo conmigo misma por la poca creatividad que a veces tengo. Gracias por el amor y el empuje que recibo desde siempre y de forma permanente. A mi amigo y colega Lucio Mansilla, a quien admiro en todo sentido, y que estuvo permanentemente a mi lado, ayudándome activa y espiritualmente. A mi directora de tesis, la Lic. Mónica Caballero, que la elegí como tal no sólo porque la respeto como docente, sino también por su compromiso profesional y personal. -

0A7aa945006f6e9505e36c8321

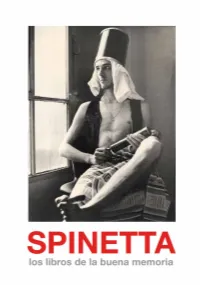

2 4 Spinetta. Los libros de la buena memoria es un homenaje a Luis Alberto Spinetta, músico y poeta genial. La exposición aúna testimonios de la vida y obra del artista. Incluye un conjunto de manuscritos inéditos, entre los que se hallan poesías, dibujos, letras de canciones, y hasta las indicaciones que le envió a un luthier para la construcción de una guitarra eléctrica. Se exhibe a su vez un vasto registro fotográfico con imágenes privadas y profesionales, documentales y artísticas. Este catálogo concluye con la presentación de su discografía completa y la imagen de tapa de su único libro de poemas publicado, Guitarra negra. Se incluyen también dos escritos compuestos especialmente para la ocasión, “Libélulas y pimientos” de Eduardo Berti y “Eternidad: lo tremendo” de Horacio González. 5 6 Pensé que habías salido de viaje acompañado de tu sombra silbando hablando con el sí mismo por atrás de la llovizna... Luis Alberto Spinetta, Guitarra negra,1978 Niño gaucho. 23 de enero de 1958 7 Spinetta. Santa Fe, 1974. Fotografía: Eduardo Martí 8 Eternidad: lo tremendo por Horacio González Llamaban la atención sus énfasis, aunque sus hipérboles eran dichas en tono hu- morístico. Quizás todo exceso, toda ponderación, es un rasgo de humor, un saludo a lo que desearíamos del mundo antes que la forma real en que el mundo se nos da. Había un extraño recitado en su forma de hablar, pero es lógico: también en su forma de cantar, siempre con una resolución final cercana a la desesperación. Un plañido retenido, insinuado apenas, pero siempre presente. ¿Pero lo definimos bien de este modo? ¿No es todo el rock, “el rock del bueno”, como decía Fogwill, completamente así? Quizás esa cauta desesperación de fondo precisaba de un fraseo que recubría todo de un lamento, con un cosquilleo gracioso. -

Entertaining the Notion of Change

44 Mara Favoretto University of Melbourne, Australia & Timothy Wilson University of Alaska Fairbanks, US “Entertaining” the Notion of Change: The Transformative Power of Performance in Argentine Pop All music can be used to create meaning and identity, but music born in a repressive political environment, in which freedom is lacking, changes the dynamic and actually facilitates that creation of meaning. This article explores some practices of protest related to pop music under dictatorship, specifically the Argentine military dictatorship of 197683, and what happens once their raison d’ệtre , the repressive regime, is removed. We examine pre and postdictatorship music styles in recent Argentine pop: rock in the 1970s80s and the current cumbia villera culture, in order to shed light on the relative roles of politics, economy and culture in the creation of pop music identity. Timothy Wilson is Assistant Professor of Spanish literature at the University of Alaska Fairbanks. He is known for his work on Argentine rock music and dictatorship, and his research interests are in the areas of governmentsponsored terror and popular cultures of resistance. Mara Favoretto is a Lecturer in Hispanic Studies at the University of Melbourne, Australia. She specialises in contemporary popular music and cultural expressions of resistance in Latin American society. Young people come to the music looking for a way to communicate with other human beings, in the middle of a society where it seems the only meeting places that are tolerated are stadiums and concert halls. ‐Claudio Kleiman, editor I believe that in the concerts there are two artists: the audience and the musician. -

Pontificia Universidad Católica Del Perú Escuela

PONTIFICIA UNIVERSIDAD CATÓLICA DEL PERÚ ESCUELA DE POSGRADO “NOS SIGUEN PEGANDO ABAJO” O EL ROCK COMO FENÓMENO DE RESISTENCIA: Narrador metadiegético, censura y lo cinematográfico en las canciones de Charly García, en el contexto de la última dictadura militar en Argentina TESIS PARA OPTAR EL GRADO DE MAGISTER EN LITERATURA HISPANOAMERICANA AUTOR MARIO GONZALO BENAVENTE SECCO ASESORA LUZ VICTORIA GUERRERO PEIRANO LIMA, PERÚ 2018 RESUMEN La siguiente tesis explora la evolución que se presenta en las letras de las canciones del músico argentino Charly García, entre los años 1974 y 1984 (antes, durante y después de la última dictadura militar de su país, conocida también como “Proceso de Reorganización Nacional”). Atravesando su participación en las bandas Sui Generis, La Máquina de Hacer Pájaros y Serú Girán, así como los inicios de su carrera solista, este estudio pretende identificar y explorar las estrategias narrativas que, desde lo literario, se hacen presentes a lo largo de la obra de García, priorizando el análisis sobre el uso del narrador metadiegético en primera persona, el mismo que utiliza Charly para plasmar una visión particular sobre la responsabilidad que tiene el artista frente a una sociedad convulsionada de la que también es parte. Asimismo, ahondaremos en el uso de referencias cinematográficas como estrategia para hablar del rol que tiene el arte en relación a (d)enunciar los atropellos que se ejecutan desde el poder, evadiendo los mecanismos de censura que la dictadura sistematizó. Palabras clave: Charly García, rock argentino, dictadura militar, Proceso de Reorganización Nacional, Sui Generis, La Máquina de Hacer Pájaros, narrador metadiegético, desapariciones forzadas, violencia política, letras de canciones. -

Entre El Rock Y La Armonía Clásico-Romántica Charly García: Between Rock and Classical-Romantic Harmony

Charly García: entre el rock y la armonía clásico-romántica Charly García: between rock and classical-romantic harmony por Diego Madoery Facultad de Bellas Artes de la Universidad Nacional de La Plata, Argentina [email protected] El presente trabajo forma parte una investigación de más amplio alcance que se propuso detectar, describir e interpretar los rasgos estilísticos de las canciones del músico de rock argentino Charly García en su primer período. Esta etapa, en la que registró la mayor parte de sus composiciones, abarca desde el primer disco del grupo Sui Géneris, Vida (1972/73) hasta Say no more de 1996. En esa investigación se observó que un conjunto de rasgos melódicos-armónicos característicos del rock atraviesan su obra de diferentes modos. En esta publicación muestro cómo la preocupación de Charly de ser considerado un músico de rock es uno de los impulsos de su estilo y se manifiesta en la combinatoria entre los rasgos propiamente rockeros y los de la armonía de la “práctica común”. Palabras clave: Charly García, análisis, melodía, armonía. The present work is part of a wider research that was proposed to detect, describe and interpret the stylistic features of the songs of argentine rock musician Charly García, in his first period. This stage, in which he recorded most of his compositions, cover from the first album of the group Sui Géneris, Vida (1972/3) to Say no more of 1996. In this research it was observed that a set of melodic-harmonic distinctive characteristic of the rock traverse its work in different ways. In this publication I show how Charly’s concern to be considered a rock musician is one of the impulses of his style and it is manifested in the combination between the properly rock’s features and those of the harmony of ‘common practice’. -

Charly García: Alegoría Y Rock

125 Charly García: alegoría y rock MARA FAVORETTO* RESUMEN: La alegoría es un figura retórica antigua que atraviesa la historia y sigue reapareciendo de diferentes maneras como un modo simbólico efectivo y maleable. Durante el régimen militar conocido como el Proceso en Argentina (1976-1983), la alegoría, en parte como reacción a la censura, aparece como principal estrategia retórica en el movimiento de resistencia conocido como rock nacional. Siguiendo la teoría de Fletcher (1964), que estudió la alegoría como método de interpretación dialéctica que pretende descifrar lo oculto en todo tipo de textos e imágenes, se exploran en este trabajo las canciones de Charly García producidas durante los primeros cinco años de este período. Este músico, uno de los principales compositores de este género, se caracteriza por componer alegorías complejas que al ser revisitadas, décadas después, continúan revelando nuevas posibles asociaciones, comprobando así el carácter transcendente de esta forma simbólica. PALABRAS CLAVE: Rock nacional; alegoría; Charly García. Charly García: allegory and rock. ABSTRACT: Allegory is an old rhetorical figure that transcended history and keeps re-emerging in different forms, as an effective and malleable symbolic mode. During the military dictatorship in Argentina -period known as the Process- (1976-1983), as a reaction to censorship, allegory seems to be one of the main rhetorical strategies used in the lyrics of the songs of the rock nacional movement. Following Fletcher (1964), for whom allegory is a dialectical method of interpretation that tries to decode what is hidden in any type of image and text, this study explores the songs composed by Charly García during the first five years of the dictatorship. -

Revista Afuera: Estudios De Crítica Cultural, No. 15, 2015

Revista Afuera: Estudios de Crítica Cultural, no. 15, 2015. “No se banca más”: Serú Girán y las transformaciones musicales del rock en la Argentina dictatorial Julián Delgado (UBA/EHESS) Resumen En una entrevista publicada en la revista Periscopio en el año 1978, Charly García se lamentaba por la poco generosa recepción del público y la crítica a su nuevo grupo, Serú Girán. Lejos de justificarse, el músico extraía de aquel hecho un diagnóstico claro: “Lo que sabemos es que tenemos que cortarla un poco con lo que nosotros sentimos y empezar a relacionarnos con la gente un poco más”. Tan sólo cuatro años después, esa relación se había desarrollado a un nivel de intensidad nunca antes logrado por una banda de rock argentino. Las canciones de Serú Girán eran, para una sociedad en plena transición democrática, una de las máximas expresiones de la “resistencia” a la dictadura militar. Este trabajo se propone problematizar el recorrido a través del cual Serú Girán se convirtió en una de los grupos más emblemáticos de la historia reciente argentina. A partir de las palabras de sus integrantes y, fundamentalmente, del análisis de sus dos primeros álbumes, se estudiará cómo la propuesta estética de la banda fue variando a lo largo del tiempo, intentando a la vez establecer las distintas mediaciones entre esta metamorfosis musical y los cambios socioculturales y políticos desarrollados durante los años del Proceso de Reorganización Nacional. Palabras clave: Serú Girán; rock argentino; dictadura; música y política Abstract In an interview published in 1978 by the magazine Periscopio, CharlyGarcía lamented by the poor reception from the audience and the critique his new group, Serú Girán, had achieved. -

Propuesta De Dos Circuitos Turísticos Por La Ciudad Autónoma De Buenos Aires Que Relacionen La Última Dictadura Cívico-Militar (1976-1983) Con El Rock Argentino

Trabajo Final de Práctica Profesional MEJOR HABLAR DE CIERTAS COSAS Propuesta de dos circuitos turísticos por la Ciudad Autónoma de Buenos Aires que relacionen la última dictadura cívico-militar (1976-1983) con el rock argentino Institución: Universidad Nacional de San Martín- Escuela de Economía y Negocios Carrera: Licenciatura en Turismo Alumnas/os: Arias, Marina ([email protected]) Rodríguez López, Joaquín ([email protected]) Villafañe, Julieta ([email protected]) Tutor: Oscar Chan ([email protected]) Fecha de presentación: 21 de noviembre de 2018 ÍNDICE CAPÍTULO 1 ......................................................................................................................................... 3 INTRODUCCIÓN .................................................................................................................................. 3 1.1 RESUMEN EJECUTIVO ................................................................................................................. 4 1.2 PROBLEMA DE INVESTIGACIÓN ................................................................................................ 4 1.3 HIPÓTESIS ..................................................................................................................................... 5 1.4 OBJETIVOS ................................................................................................................................... 5 1.4.1 OBJETIVOS GENERALES ............................................................................................................. -

EL MELÓMANO EL MELÓMANO Es Un Juego De Mesa Para Los Amantes De La Música

UN JUEGO de regalo PARA JUGAR EN CUARENTENA Somos JUEGOS MALDÓN Una empresa familiar argentina que se dedica a hacer juegos de mesa. Estamos convencidos de que JUGAR es una manera muy sana de combatir el encierro. Por eso armamos versiones reducidas y adaptadas de nuestros juegos, para que todos los que están en su casa en cuarentena puedan jugarlos. Nuestro granito de arena para hacer la situación más amena. @juegosmaldon www.maldon.com.ar ¡Quedate en casa! #LaCuarentenaSePasaJugando EL MELÓMANO EL MELÓMANO es un juego de mesa para los amantes de la música. ¿Sabés de memoria todas las canciones? Este juego es para vos. Cada tarjeta tiene un fragmento de una can- ción, con 2 palabras borradas para cantar y completar, ¡no importa cuán desafinado sea! y luego contestar una serie de preguntas rela- cionadas al tema o la banda. Todos son grandes éxitos en español. DURACIÓN DE LA PARTIDA 35 minutos (aprox.) CANTIDAD DE JUGADORES 2+ (Puede jugarse por equipos y pueden estar en distintas casas a través de videoconferencia) EDAD SUGERIDA + 15 años QUÉ NECESITAMOS Un teléfono para ver este archivo Cronómetro (preparado en 2 min.) dinámica del juego Cada partida consta de 12 tarjetas. En este archivo hay 2 partidas. Empieza contestando el que propuso jugar. Cuando todos estén listos, empieza el juego. Van a ver una tarjeta como esta: El jugador deberá cantar y completar las dos palabras que faltan, y luego contestar las 4 preguntas que se encuentran debajo. ¡Tienen 2 minutos para responder! Cada jugador o equipo contesta 1 tarjeta y se pasa el turno. -

ROCK CHILENO Canto Nuevo?

ROCK CHILENO canto nuevo? 11 ni lncx! canc I ENERI encuesta: 400 JVENES OPINAN SOBRE CHILE LA PAREJA... DISPAREJA? entrevista con siclogo est en los hechos La verdad est en los hechos... y usted tiene derecho a saberla. El Diario de Cooperativa est con la verdad y la dice. En sus cuatro ediciones diarias le informa cundo y porqu se pro ducen las noticias para que usted se forme su propia opi nin. El Diario de Cooperativa se transmite de 6:00 a 8:30, de 13:15 a 14:00, de 19:00 a 20:00 y de 00 a 0:20 horas. Radio Cooperativa En el 76 de su dial A.M. este nmero SUI GENERIS uni a la to Mestre y Charly Garca ya msica del rock la poesa no son Sui Generis, cada uno corriente de nuestras ciuda con su propio grupo. rock des, ac en el sur del mundo. Un grupo de argenti las fronteras Tal vez por eso los hemos no que traspas venido oyendo todos estos del rock y las fronteras argen aos y nos juntamos ahora a tinas. Muy sui generis, pues. cantarlos, incluso cuando Ni- Decir ROCK CHILENO y "Msica de locos, me crispa mi ta que salte una lluvia de prejui los nervios" deca cios,hasta ahora ha sido simul Crispina. tneo. "Drogadictos, aliena La Rene se sac las ante dos, tarrientos, imitadores, ojeras y las orejeras y fue a un proimperialistas" (todo de recital. Parece que le gust corrido) dicen por ah. porque todava no vuelve. CHILE COMO PREGUN una isla de paz, etctera) pero, TA,formulada a 400 estu tambin, reparos gruesos: ce diantes de enseanza media y santa, concentracin de la mate los nuevos institutos profesio riqueza, individualismo, nales por investigadores de rialismo.