Entertaining the Notion of Change

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Tesita Chiletiña Listita Pal Exito

Universidad Austral de Chile Facultad de Filosofía y Humanidades Escuela de Historia y Ciencias Sociales Profesor Patrocinante: Karen Alfaro Monsalve Instituto Ciencias Sociales LA CANCIÓN DE PROTESTA EN EL CHILE ACTUAL: ANÁLISIS DEL MOVIMIENTO CULTURAL DE “TROVADORES INDEPENDIENTES” 2000-2011 Seminario de Título para optar al título de profesor de Historia y Ciencias Sociales ANDREA GIORETTI MALDONADO SANCHEZ Valdivia Octubre, 2011 TABLA DE CONTENIDOS CONTENIDO PÁGINA INTRODUCCION 4 CAPITULO I: FORMULACION DEL PROBLEMA 7 1.1 Idea de Investigación 7 1.2 Planteamiento del problema 8 1.3 Pregunta 10 1.4 Hipótesis 10 1.5 Objetivo General 10 1.6 Objetivos Específicos 10 CAPITULO II: MARCO METODOLÓGICO 2.1 Localización espacio-temporal de la investigación 11 2.2 Entidades de Interés 11 2.3 Variables que se medirán 12 2.4 Fuente de Datos 12 2.5 Procedimientos de recolección y análisis de datos 13 CAPITULO III: MARCO TEÒRICO: Música y política, Canción Protesta. Chile 1973-2010 3.1 Cultura, música y política: De la infraestructura a la superestructura 14 1.- Estudios Culturales en la disciplina histórica ¿Algo Nuevo? 22 3.2 Musicología y Música Popular: La juventud e identidad en América Latina 1.-La música popular en los estudios culturales: conceptualización y antecedentes 25 1.1.-Entre lo popular y lo formal: La validación de la música popular como campo de estudio. Antecedentes históricos. 28 2.-El estudio de la música popular en Latinoamérica: la diversidad musical de un continente diverso. 29 3.-La musicología en la historiografía: desde la escuela de los Annales a la Interdisciplinaridad. 35 4.-La semiótica: el nuevo paso de la musicología 38 5.- Los efectos de la música popular en la juventud latinoamericana: Formadora de identidad y pertenencia. -

Rock Nacional” and Revolutionary Politics: the Making of a Youth Culture of Contestation in Argentina, 1966–1976

“Rock Nacional” and Revolutionary Politics: The Making of a Youth Culture of Contestation in Argentina, 1966–1976 Valeria Manzano The Americas, Volume 70, Number 3, January 2014, pp. 393-427 (Article) Published by The Academy of American Franciscan History DOI: 10.1353/tam.2014.0030 For additional information about this article http://muse.jhu.edu/journals/tam/summary/v070/70.3.manzano.html Access provided by Chicago Library (10 Feb 2014 08:01 GMT) T HE A MERICAS 70:3/January 2014/393–427 COPYRIGHT BY THE ACADEMY OF AMERICAN FRANCISCAN HISTORY “ROCK NACIONAL” AND REVOLUTIONARY POLITICS: The Making of a Youth Culture of Contestation in Argentina, 1966–1976 n March 30, 1973, three weeks after Héctor Cámpora won the first presidential elections in which candidates on a Peronist ticket could Orun since 1955, rock producer Jorge Álvarez, himself a sympathizer of left-wing Peronism, carried out a peculiar celebration. Convinced that Cám- pora’s triumph had been propelled by young people’s zeal—as expressed in their increasing affiliation with the Juventud Peronista (Peronist Youth, or JP), an organization linked to the Montoneros—he convened a rock festival, at which the most prominent bands and singers of what journalists had begun to dub rock nacional went onstage. Among them were La Pesada del Rock- ’n’Roll, the duo Sui Géneris, and Luis Alberto Spinetta with Pescado Rabioso. In spite of the rain, 20,000 people attended the “Festival of Liberation,” mostly “muchachos from every working- and middle-class corner of Buenos Aires,” as one journalist depicted them, also noting that while the JP tried to raise chants from the audience, the “boys” acted as if they were “untouched by the political overtones of the festival.”1 Rather atypical, this event was nonetheless significant. -

Los Vallenatos De La Cumbia Discografia

Los Vallenatos De La Cumbia Discografia Los Vallenatos De La Cumbia Discografia 1 / 3 Descubre las últimas novedades de tus artistas favoritos en CDs y vinilos. Compra ya. Detalles del producto. ASIN : B00EZ6APC8. Opiniones de clientes .... los vallenatos de la cumbia discografia, los vallenatos de la cumbia discografia mega, descargar discografia de los vallenatos de la cumbia, descargar .... PDF | Este trabajo trata la manera en que se da la transnacionalización del vallenato y la cumbia entre Colombia y México, enfatizando cómo ... Escucha Sabor A Vallenato de Los Vallenatos De La Cumbia en Deezer. Fanny, Regalo El Corazon, Sal Y Agua.... No Pude Quitarte las Espinas / La Decision Vallenata - Video Oficial ... Andrés Landero y su Conjunto El Rey de la Cumbia ECO / Discos Fuentes 1978 | Global .... See more of Adictos a la Musica Colombiana y Vallenata on Facebook. Log In. Forgot account? or. Create New Account. Not Now. Related Pages. SonVallenato .... Descargar y Escuchar Música Mp3 Gratis, Album De Todos Los Géneros Musicales, Videos Oficiales y Noticias Sobre Sus Artistas Favoritos.. Encuentra Cd Los Conquistadores Vallenatos en Mercado Libre Venezuela. Descubre la mejor ... Discografia De Diomedes Diaz- 390 Canciones. Bs.3.700.000 ... Los Bonchones.al Son De Vallenato,cumbia Y El Porro Cd Qq2. Bs.3.715.024. los vallenatos de la cumbia discografia mega los vallenatos de la cumbia discografia mega, descargar discografia de los vallenatos de la cumbia, los vallenatos de la cumbia discografia, descargar discografia completa de los vallenatos de la cumbia, discografia de los vallenatos de la cumbia por mega, discografia vallenatos de la cumbia, vallenatos de la cumbia discografia Jump to Descargar La Tropa Vallenata MP3 Gratis - YUMP3 — Descargar La Tropa Vallenata Mp3. -

Digital Archiving on Chilean Music and Musicians, Part 2 by Eileen Karmy

H-LatAm Digital Archiving on Chilean Music and Musicians, Part 2 by Eileen Karmy Blog Post published by Gretchen Pierce on Sunday, April 26, 2020 We continue our digital mini-series with the second of two posts about online resources for Chilean music. If you missed the first one, click here. Eileen Karmy is a music scholar interested in music politics, labor history, and archival research. She completed her PhD in Music at the University of Glasgow in 2019 with a thesis on the development of musicians’ unions in Chile. She has researched on popular music in Chile, especially cumbia, tango, and Nueva Canción. She regularly disseminates her research through articles, blog posts, films, and digital repositories. She created the digital archive of musicians’ organizations in Valparaíso (memoriamusicalvalpo.cl) in 2015. She has published books and journal articles on Chilean New Song, tango orchestras, tropical music, musicians’ working conditions, and the social history of musicians’ organizations in Chile. These include the book ¡Hagan un trencito! Siguiendo los pasos de la memoria cumbianchera en Chile (1949-1989), co-authored with Ardito, Mardones, and Vargas (2016), and her article “Musical Mutualism in Valparaiso during the Rise of the Labor Movement (1893–1931),” Popular Music and Society, 40, no. 5, 2017. Digital Archiving on Chilean Music and Musicians, Part 2 In this post, I share a list of digital sources that hold relevant material and specific information about music and musicians in Chile that might be useful for scholars interested in researching Chilean music and culture in general. While I did not use these sites for my research on musicians’ unions I am familiar with them because they proved useful in my previous studies of Chilean popular music history. -

Music and Spiritual Feminism: Religious Concepts and Aesthetics

Music and spiritual feminism: Religious concepts and aesthe� cs in recent musical proposals by women ar� sts. MERCEDES LISKA PhD in Social Sciences at University of Buenos Aires. Researcher at CONICET (National Council of Scientifi c and Technical Research). Also works at Gino Germani´s Institute (UBA) and teaches at the Communication Sciences Volume 38 Graduation Program at UBA, and at the Manuel de Falla Conservatory as well. issue 1 / 2019 Email: [email protected] ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0001-9692-6446 Contracampo e-ISSN 2238-2577 Niterói (RJ), 38 (1) abr/2019-jul/2019 Contracampo – Brazilian Journal of Communication is a quarterly publication of the Graduate Programme in Communication Studies (PPGCOM) at Fluminense Federal University (UFF). It aims to contribute to critical refl ection within the fi eld of Media Studies, being a space for dissemination of research and scientifi c thought. TO REFERENCE THIS ARTICLE, PLEASE USE THE FOLLOWING CITATION: Liska, M. (2019). Music and spiritual feminism. Religious concepts and aesthetics in recent musical proposals by women artists. Contracampo – Brazilian Journal of Communication, 38 (1). Submitted on: 03/11/2019 / Accepted on: 04/23/2019 DOI – http://dx.doi.org/10.22409/contracampo.v38i1.28214 Abstract The spiritual feminism appears in the proposal of diverse women artists of Latin American popular music created recently. References linked to personal and social growth and well-being, to energy balance and the ancestral feminine powers, that are manifested in the poetic and thematic language of songs, in the visual, audiovisual and performative composition of the recitals. A set of multi religious representations present in diff erent musical aesthetics contribute to visualize female powers silenced by the patriarchal system. -

Samba, Rumba, Cha-Cha, Salsa, Merengue, Cumbia, Flamenco, Tango, Bolero

SAMBA, RUMBA, CHA-CHA, SALSA, MERENGUE, CUMBIA, FLAMENCO, TANGO, BOLERO PROMOTIONAL MATERIAL DAVID GIARDINA Guitarist / Manager 860.568.1172 [email protected] www.gozaband.com ABOUT GOZA We are pleased to present to you GOZA - an engaging Latin/Latin Jazz musical ensemble comprised of Connecticut’s most seasoned and versatile musicians. GOZA (Spanish for Joy) performs exciting music and dance rhythms from Latin America, Brazil and Spain with guitar, violin, horns, Latin percussion and beautiful, romantic vocals. Goza rhythms include: samba, rumba cha-cha, salsa, cumbia, flamenco, tango, and bolero and num- bers by Jobim, Tito Puente, Gipsy Kings, Buena Vista, Rollins and Dizzy. We also have many originals and arrangements of Beatles, Santana, Stevie Wonder, Van Morrison, Guns & Roses and Rodrigo y Gabriela. Click here for repertoire. Goza has performed multiple times at the Mohegan Sun Wolfden, Hartford Wadsworth Atheneum, Elizabeth Park in West Hartford, River Camelot Cruises, festivals, colleges, libraries and clubs throughout New England. They are listed with many top agencies including James Daniels, Soloman, East West, Landerman, Pyramid, Cutting Edge and have played hundreds of weddings and similar functions. Regular performances in the Hartford area include venues such as: Casona, Chango Rosa, La Tavola Ristorante, Arthur Murray Dance Studio and Elizabeth Park. For more information about GOZA and for our performance schedule, please visit our website at www.gozaband.com or call David Giardina at 860.568-1172. We look forward -

Grilla De Horarios De Estudio Urbano

GRILLA DE HORARIOS DE ESTUDIO URBANO LUNES 18 a 20 hs. - CURSO BÁSICO DE PROTOOLS | Francisco Rojas | 5 de mayo 18 a 20 hs. - EDICIÓN INDEPENDIENTE DE DISCOS | Fabio Suárez | 19 de mayo 19 a 21 hs. - CIRCULACIÓN DE MÚSICA POR LA WEB | Matías Erroz | 19 de mayo 19 a 21 hs. - CANTO EN EL ROCK | María Rosa Yorio | 5 de mayo 20 a 22 hs. - ARTE Y TECNOLOGÍA MULTIMEDIA | Alejandra Isler | 19 de mayo MARTES 19 a 21 hs. - INTRO A DJ | Carlos Ruiz y Ramón Gallo (Adisc) | 6 de mayo 19 a 21 hs. - ARTE DE TAPA DE DISCOS | Ezequiel Black | 29 de abril 19 a 21 hs. - VIAJE POR LA MENTE DE LOS GENIOS DEL ROCK | Pipo Lernoud | 29 de abril 19 a 21 hs. - ARREGLOS Y COMPOSICIÓN EN LA MÚSICA POPULAR | Pollo Raffo | comienza en junio, al finalizar el ciclo de Pipo Lernoud MIÉRCOLES 17 a 19 hs. - TALLER LITERARIO | Ariel Bermani | 30 de abril 17 a 19 hs. - TALLER DE GRABACIÓN | Mariano Ondarts | 30 de abril 18 a 20 hs. - PERIODISMO Y ROCK | Matías Capelli | 7 de mayo 19 a 21 hs. - ABLETON LIVE | Eduardo Sormani | 30 de abril 19 a 21 hs. - REASON | Eduardo Sormani | comienza en junio, al finalizar el curso de Ableton Live 19 a 21 hs. - COMUNICACIÓN Y MANAGEMENT DE PROYECTOS MUSICALES | Leandro Frías | 30 de abril JUEVES 17 a 19 hs. - SONIDO EN VIVO | Pablo González Martínez | 8 de mayo 17:30 a 19:30 hs. - LA CÁMARA POR ASALTO | Pablo Klappenbach | 8 de mayo 19 a 21 hs. - REVOLUCIÓN DEL ROCK | Alfredo Rosso | 8 de mayo 19:30 a 21:30 hs. -

Disertación Final

PONTIFICIA UNIVERSIDAD CATÓLICA DEL ECUADOR FACULTAD DE CIENCIAS ADMINISTRATIVAS Y CONTABLES DESARROLLO DE UN PLAN ESTRATÉGICO DE MARKETING DE LA BANDA CUMBIA DEL BARRIO EN EL MERCADO MUSICAL DE LA CIUDAD DE QUITO TRABAJO DE TITULACIÓN PREVIA LA OBTENCIÓN DEL TÍTULO DE INGENIERÍA COMERCIAL LUIS ALBERTO ANDINO LÓPEZ DIRECTOR: ING. VICENTE TORRES QUITO, MAYO 2014 DIRECTOR DE DISERTACIÓN: Ing. Vicente Torres INFORMANTES: Ing. Jaime Benalcázar Mtr. Roberto Ordóñez ii DEDICATORIA Este trabajo está dedicado a mis padres, a todo el apoyo que me han brindado en estos años de estudio. Va dedicado a la gente que siempre me ayudó con su voluntad, su tiempo y esfuerzo para desarrollar este tema en especial una merecida dedicatoria a mis amigos de la "Cumbia del Barrio", Diana, Felipe, Leonardo, Julio, Fernando, Xavicho, Igor. Y todas aquellas personas que nos acompañaron en nuestra travesía musical. Alberto iii AGRADECIMIENTO A todas las personas que me acompañaron en este camino musical, a los amigos de la Cumbia del Barrio que estuvieron presentes en todos los conciertos que podían asistir. A aquellas personas que siempre estuvieron a mi lado brindándome su apoyo moral y sus conocimientos en este proyecto. Agradezco a aquellas personas y medios de comunicación que nos dieron la apertura para poder compartir nuestra música con el público en general, así mencionó a Radio La Luna, Radio Quito y en especial a su programa "Territorio Cumbia". Alberto iv ÍNDICE INTRODUCCIÓN, 1 1 ANÁLISIS SITUACIONAL, 3 1.1 EL ENTORNO EXTERNO, 3 1.1.1 Competencia, 4 1.1.2 -

Escúchame, Alúmbrame. Apuntes Sobre El Canon De “La Música Joven”

ISSN Escúchame, alúmbrame. 0329-2142 Apuntes de Apuntes sobre el canon de “la investigación del CECYP música joven” argentina entre 2015. Año XVII. 1966 y 1973 Nº 25. pp. 11-25. Recibido: 20/03/2015. Aceptado: 5/05/2015. Sergio Pujol* Tema central: Rock I. No caben dudas de que estamos viviendo un tiempo de fuerte interroga- ción sobre el pasado de lo que alguna vez se llamó “la música joven ar- gentina”. Esa música ya no es joven si, apelando a la metáfora biológica y más allá de las edades de sus oyentes, la pensamos como género desarro- llado en el tiempo según etapas de crecimiento y maduración autónomas. Veámoslo de esta manera: entre el primer éxito de Los Gatos y el segundo CD de Acorazado Potemkin ha transcurrido la misma cantidad de años que la que separa la grabación de “Mi noche triste” por Carlos Gardel y el debut del quinteto de Astor Piazzolla. ¿Es mucho, no? En 2013 la revista Rolling Stone edición argentina dedicó un número es- pecial –no fue el primero– a los 100 mejores discos del rock nacional, en un arco que iba de 1967 a 2009. Entre los primeros 20 seleccionados, 9 fueron grabados antes de 1983, el año del regreso de la democracia. Esto revela que, en el imaginario de la cultura rock, el núcleo duro de su obra apuntes precede la época de mayor crecimiento comercial. Esto afirmaría la idea CECYP de una época heroica y proactiva, expurgada de intereses económicos e ideológicamente sostenida en el anticonformismo de la contracultura es- tadounidense adaptada al contexto argentino. -

Charly García

Charly García ‘El Prócer Oculto’ [Un relato a través de entrevistas a Sergio Marchi y Alfredo Rosso] Alumna: Laura Impellizzeri ‘Charly García: El Prócer Oculto’ Comunicación Social - UNLP 2017 Directora: Prof. Mónica Caballero Agradecimientos. La última etapa de la carrera es la elaboración del T.I.F. [Trabajo Integrador Final] que lleva tiempo, dedicación, ganas y esfuerzo. Por supuesto que estos elementos no confluyen siempre; no están de forma permanente ni simultánea. En esos ‘lapsus’ de cansancio, de tener la mente en blanco porque no hay ideas que plasmar, aparecen los estímulos, las ayudas extra-académicas que nos dan el aliento necesario para seguir adelante. En mi caso, necesito agradecer profundamente a los dos pilares de mi vida que son mi madre Julia y mi padre Miguel, quienes, además de darme educación y amor desde que nací, me han dado la seguridad, la confianza y el apoyo incondicional en cada paso que di y doy en mi carrera. También agradezco a mi hermana Marta por haberme acercado, de alguna forma, a Charly García. No pueden faltar mis amigos. Estuvieron ahí ante las permanentes caídas y el enojo conmigo misma por la poca creatividad que a veces tengo. Gracias por el amor y el empuje que recibo desde siempre y de forma permanente. A mi amigo y colega Lucio Mansilla, a quien admiro en todo sentido, y que estuvo permanentemente a mi lado, ayudándome activa y espiritualmente. A mi directora de tesis, la Lic. Mónica Caballero, que la elegí como tal no sólo porque la respeto como docente, sino también por su compromiso profesional y personal. -

Videomemes Musicales, Punctum, Contrapunto Cognitivo Y Lecturas

“The Who live in Sinaloa”: videomemes musicales, punctum, contrapunto cognitivo y lecturas oblicuas “The Who live in Sinaloa”: Musical video memes, punctum, cognitive counterpoint and oblique readings por Rubén López-Cano Escola Superior de Música de Catalunya, España [email protected] Los internet memes son unidades culturales de contenido digital multimedia que se propagan inten- samente por la red en un proceso en el que son intervenidos, remezclados, adaptados, apropiados y transformados por sus usuarios una y otra vez. Su dispersión sigue estructuras, reglas, narrativas y argumentos que se matizan, intensifican o cambian constantemente dando lugar a conversaciones digi- tales de diverso tipo. Después de una introducción general a la memética, en este trabajo se analizan a fondo algunos aspectos del meme Cover Heavy cumbia. En este, los prosumidores montan escenas de conciertos de bandas de rock duro como Metallica, Korn o Guns N’ Roses, sobre músicas de escenas locales latinoamericanas como cumbia, balada, cuarteto cordobés, narcocorridos o música de banda de México. El análisis a profundidad de sus estrategias de sincronización audiovisual de materiales tan heterogéneos nos permitirá conocer a fondo su funcionamiento interno, sus mecanismos lúdicos, sus ganchos de interacción cognitiva y las lecturas paradójicas, intermitentes, reflexivas o discursivas que propician. En el análisis se han empleado herramientas teóricas del análisis del audiovisual, conceptos de los estudios acerca del gesto musical y del análisis de discursos no verbales de naturaleza semiótica con acento en lo social y pragmático. Palabras clave: Internet meme, remix, remezcla digital, música plebeya, videomeme, memética, reciclaje digital musical. Internet memes are cultural units of digital multimedia content that are spread intensely through the network in a process in which they are intervened, remixed, adapted and transformed by their users over and over again. -

0A7aa945006f6e9505e36c8321

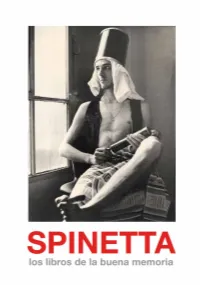

2 4 Spinetta. Los libros de la buena memoria es un homenaje a Luis Alberto Spinetta, músico y poeta genial. La exposición aúna testimonios de la vida y obra del artista. Incluye un conjunto de manuscritos inéditos, entre los que se hallan poesías, dibujos, letras de canciones, y hasta las indicaciones que le envió a un luthier para la construcción de una guitarra eléctrica. Se exhibe a su vez un vasto registro fotográfico con imágenes privadas y profesionales, documentales y artísticas. Este catálogo concluye con la presentación de su discografía completa y la imagen de tapa de su único libro de poemas publicado, Guitarra negra. Se incluyen también dos escritos compuestos especialmente para la ocasión, “Libélulas y pimientos” de Eduardo Berti y “Eternidad: lo tremendo” de Horacio González. 5 6 Pensé que habías salido de viaje acompañado de tu sombra silbando hablando con el sí mismo por atrás de la llovizna... Luis Alberto Spinetta, Guitarra negra,1978 Niño gaucho. 23 de enero de 1958 7 Spinetta. Santa Fe, 1974. Fotografía: Eduardo Martí 8 Eternidad: lo tremendo por Horacio González Llamaban la atención sus énfasis, aunque sus hipérboles eran dichas en tono hu- morístico. Quizás todo exceso, toda ponderación, es un rasgo de humor, un saludo a lo que desearíamos del mundo antes que la forma real en que el mundo se nos da. Había un extraño recitado en su forma de hablar, pero es lógico: también en su forma de cantar, siempre con una resolución final cercana a la desesperación. Un plañido retenido, insinuado apenas, pero siempre presente. ¿Pero lo definimos bien de este modo? ¿No es todo el rock, “el rock del bueno”, como decía Fogwill, completamente así? Quizás esa cauta desesperación de fondo precisaba de un fraseo que recubría todo de un lamento, con un cosquilleo gracioso.