Education Kit

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Journal of a London Playgoer from 1851 to 1866

BOOKS AND PAPERS HENRY MORLEY 1851 1866 II THE JOURNAL LONDON PLAYGOER FROM 1851 TO 1866 HENRY MORLEY, LL.D, EMERITUS PROFESSOR OF ENGLISH LITERATURE IN UNIVERSITY COLLEGE. LONDON LONDON GEORGE ROUTLEDGE AND SONS, LIMITED BROADWAY, LUDGATE HILL GLASGOW, MANCHESTER, AND NEW. .YORK < ' ' PN PROLOGUE. THE writer who first taught Englishmen to look for prin- ciples worth study in the common use of speech, expecting censure for choice of a topic without dignity, excused him- self with this tale out of Aristotle. When Heraclitus lived, a famous Greek, there were some persons, led by curiosity to see him, who found him warming himself in his kitchen, and paused at the threshold because of the meanness of the " place. But the philosopher said lo them, Enter boldly, " for here too there are Gods". The Gods" in the play- house are, indeed, those who receive outside its walls least honour among men, and they have a present right to be its Gods, I fear, not only because they are throned aloft, but also because theirs is the mind that regulates the action of the mimic world below. They rule, and why ? Is not the educated man himself to blame when he turns with a shrug from the too often humiliating list of an evening's perform- ances at all the theatres, to say lightly that the stage is ruined, and thereupon make merit of withdrawing all atten- tion from the players ? The better the stage the better the town. If the stage were what it ought to be, and what good it actors heartily desire to make it, would teach the public to appreciate what is most worthy also in the sister arts, while its own influence would be very strong for good. -

(Unabridged) K

Audiobook 12 Before 13 Greenwald, Lisa Audiobook 13 and Counting Greenwald, Lisa Audiobook A Nancy Drew Christmas (unabridged) Keene, Carolyn Audiobook A Virgin River Christmas:(unabridged) Carr, Robyn Audiobook Abby in Oz Mlynowski, Sarah Audiobook Admission Buxbaum, Julie Audiobook Adventures of Captain Underpants Pilkey, Dav Audiobook All That Glitters Steel, Danielle Audiobook All Your Twisted Secrets Urban, Diana Audiobook Allies Gratz, Alan ; Cline, Jamie McGee, Katharine ; Pressley, Audiobook American Royals Brittany Audiobook Archenemies Meyer, Marissa Audiobook Artemis Fowl Colfer, Eoin Tyson, Neil deGrasse ; Mone, Audiobook Astrophysics for Young People in a Hurry Gregory Audiobook Aurora Rising Kaufman, Amie ; Kristoff, Jay Audiobook Awakening Roberts, Nora Audiobook Awesome Dog 5000 Dean, Justin Audiobook Bad Seed John, Jory Audiobook Bait and Witch(unabridged) Sanders, Angela M. Audiobook Batman Lu, Marie Audiobook Best Babysitters Ever Cala, Caroline Audiobook Best of Me Sedaris, David DiCamillo, Kate ; Marie, Audiobook Beverly, Right Here Jorjeana Audiobook Big Nate Flips Out Peirce, Lincoln Audiobook Big Nate Goes for Broke Peirce, Lincoln Audiobook Big Nate in the Zone Peirce, Lincoln Mlynowski, Sarah ; Myracle, Audiobook Big Shrink Lauren ; Jenkins, Emily Audiobook Black Panther Smith, Ronald L. Audiobook Blood in the Dust Johnstone, William W. Mass, Wendy ; Stead, Audiobook Bob Rebecca Audiobook Book With No Pictures Novak, B. J. Audiobook Boxcar Children Warner, Gertrude Chandler Audiobook Brightest Night Sutherland, -

Cross-Dressing and Gender Performativity in Japanese Media Sheena Marie Woods University of Arkansas, Fayetteville

University of Arkansas, Fayetteville ScholarWorks@UARK Theses and Dissertations 7-2015 The aF scination of Manga: Cross-dressing and Gender Performativity in Japanese Media Sheena Marie Woods University of Arkansas, Fayetteville Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarworks.uark.edu/etd Part of the Japanese Studies Commons, Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender Studies Commons, Theatre History Commons, and the Translation Studies Commons Recommended Citation Woods, Sheena Marie, "The asF cination of Manga: Cross-dressing and Gender Performativity in Japanese Media" (2015). Theses and Dissertations. 1273. http://scholarworks.uark.edu/etd/1273 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by ScholarWorks@UARK. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UARK. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. 44 The Fascination of Manga: Cross-dressing and Gender Performativity in Japanese Media A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Comparative Literature and Cultural Studies By Sheena Woods University of Arkansas Bachelor of Arts in International Relations, 2012 University of Arkansas Bachelor of Arts in Asian Studies, 2012 July 2015 University of Arkansas This thesis is approved for recommendation to the Graduate Council. _______________________ Dr. Elizabeth Markham Thesis Director ________________________ ________________________ Dr. Tatsuya Fukushima Dr. Rembrandt Wolpert Committee Member Committee Member 4 4 Abstract The performativity of gender through cross-dressing has been a staple in Japanese media throughout the centuries. This thesis engages with the pervasiveness of cross-dressing in popular Japanese media, from the modern shōjo gender-bender genre of manga and anime to the traditional Japanese theatre. -

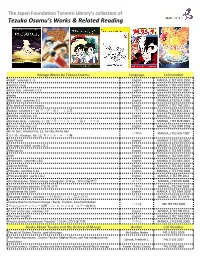

Tezuka Osamu Booklist

The Japan Foundation Toronto Library’s collection of Tezuka Osamu’s Works & Related Reading Manga Works by Tezuka Osamu Language Call number Adolf : volumes 1 - 5 English MANGA_E TEZ ADO 1995 Apollo's song English MANGA_E TEZ APO 2007 Astro boy : volumes 1-12 English MANGA_E TEZ AST 2002 Ayako English MANGA_E TEZ AYA 2010 Black Jack : volumes 1-3 English MANGA_E TEZ BLA 2008 The book of human insects English MANGA_E TEZ THE 2011 Budda : volumes 1~14 ブッダ:第1-14巻 日本語 MANGA_J TEZ BUD 2011 Buddha : volumes 1-8 English MANGA_E TEZ BUD 2003 Burakku Jakku : volumes 1~22 ブラックジャック:第1-22巻 日本語 MANGA_J TEZ BUR 2004 Dororo : Volumes 1-3 English MANGA_E TEZ DOR 2008 Hi no tori : Hinotori No. 12, Girisha, Roma hen 日本語 MANGA_J TEZ HIN 1987 火の鳥 : Hinotori. No. 12, ギリシャ・ローマ編 Lost World English MANGA_E TEZ LOS 2003 Message to Adolf : parts 1 & 2 English MANGA_E TEZ MES 2012 Metropolis English MANGA_E TEZ MET 2003 MW English MANGA_E TEZ MW 2007 Nextworld : volumes 1 &2 English MANGA_E TEZ NEX 2003 Ode to Kirihito English MANGA_E TEZ ODE 2006 Phoenix : volumes 1-12 English MANGA_E TEZ PHO 2003 Princess knight : parts 1 & 2 English MANGA_E TEZ PRI 2011 Shintakarajima : boken manga monogatari 新寳島 : 冒険漫画物語 日本語 MANGA_J TEZ SHI 2009 Shintakarajima tokuhon 新寶島 読本 日本語 MANGA_J TEZ SHI 2009 Swallowing the Earth English MANGA_E TEZ SWA 2009 Tetsuwan Atomu : volumes 1~17 鉄腕アトム:第 1-17 巻 日本語 MANGA_J TEZ TET 1979 Tezuka Osamu no Dizuni manga : Banbi, Pinokio : kara fukkokuban 日本語 REF TEZ TEZ 2005 手塚治虫のディズニー漫画 : バンビ, ピノキオ : カラー復刻版 Triton of the sea : volumes 1-2 English MANGA_E TEZ TRI 2013 The Twin Knights English MANGA_E TEZ TWI 2013 Tezuka Osamu kessakusen "kazoku"手塚治虫傑作選 家族 日本語 MANGA_J TEZ KAZ 2008 Books About Tezuka and the History of Manga Author Call Number The art of Osamu Tezuka : god of manga McCarthy, Helen 741.5 M32 2009 The Astro Boy essays : Osamu Tezuka, Mighty Atom, and the manga/anime Schodt, Frederik L. -

Tezuka Dossier.Indd

Dossier de premsa Organitza Col·labora Del 31 d’octubre del 2019 al 6 de gener del 2020 Organitza i produeix: FICOMIC amb la col·laboració del Museu Nacional d’Art de Catalunya Comissari: Stéphane Beaujean Sala d’exposicions temporals 2 Astro Boy © Tezuka productions • El mangaka Osamu Tezuka, també conegut com a Déu del Manga per la seva immensa aportació a la vinyeta japonesa, és el protagonista d’una exposició que es podrà veure durant gairebé un parell de mesos al Museu Nacional d’Art de Catalunya, i que està integrada per gairebé 200 originals d’aquest autor. • L’exposició ha estat produïda per FICOMIC gràcies a l’estreta col·laboració amb el Mu- seu Nacional d’Art de Catalunya, Tezuka Productions i el Festival de la Bande Desinneè d’Angulema. Osamu Tezuka, el Déu del Manga és una mostra sense precedents al nos- tre país, que vol donar a conèixer de més a prop l’obra d’un creador vital per entendre l’evolució del manga després de la Segona Guerra Mundial, i també a un dels autors de manga més prestigiosos i prolífi cs a nivell mundial. • Osamu Tezuka, el Déu del Manga es podrà visitar a partir del 31 d’octubre d’aquest any, coincidint amb l’inici de la 25a edició del Manga Barcelona, fi ns al 6 de gener de 2020. 3 Fénix © Tezuka productions Oda a Kirihito © Tezuka productions El còmic al Museu Nacional Aquest projecte forma part de l’acord de col·laboració entre FICOMIC i el Museu Nacional d’Art de Catalunya gràcies al qual també es va produir l’exposició Corto Maltés, de Juan Díaz Canales i Rubén Pellejero, o la més recent El Víbora. -

Gesamtkatalog Japan DVD Zum Download

DVD Japan (Kurzübersicht) Nr. 33 Juli 2004 Best.Nr. Titel Termin Preis** Animation 50009604 .Hack // Sign (DD & PCM) 25.08.2002 109,90 € 50011539 .Hack//Legend Of Twilight Bracelet Vol. 1 25.04.2003 94,90 € 50010369 .Hack//Sign Vol. 5 (PCM) 25.11.2002 109,90 € 50010725 .Hack//Sign Vol. 6 (PCM) 21.12.2002 109,90 € 50011314 .Hack//Sign Vol. 9 (PCM) 28.03.2003 109,90 € 50002669 1001 Nights 25.08.2000 60,90 € 50001721 1001 Nights (1998) 18.12.1999 154,90 € 50003015 101 Dalmatians 18.10.2000 78,90 € 50010612 101 Dalmatians 2: Patch's London Adventure 06.12.2002 64,90 € 50008214 11 Nin Iru! 22.03.2002 79,90 € 50010894 12 Kokuki 8-10 Vol. 4 (DD) 16.01.2003 79,90 € 50007134 24 Hours TV Special Animation 1978-1981 22.11.2001 281,90 € 50009578 3chome No Tama Onegai! Momochan Wo Sagashite! (DD) 21.08.2002 49,90 € 50011428 3x3 Eyes DVD Box (DD) 21.05.2003 263,90 € 50008995 7 Nin Me No Nana 4 Jikanme 03.07.2002 105,90 € 50008431 7 Nin No Nana 2jikanme 01.05.2002 89,90 € 50008430 7 Nin No Nana 4jikanme 03.07.2002 127,90 € 50008190 7 Nin No Nana Question 1 03.04.2002 89,90 € 50001393 A.D. Police 25.07.1999 94,90 € 50001719 Aardman Collection (1989-96) 24.12.1999 64,90 € 50015065 Abaranger Vs Hurricanger 21.03.2004 75,90 € 50009732 Abenobasi Maho Syotengai Vol. 4 (DD) 02.10.2002 89,90 € 50007135 Ace Wo Nerae - Theater Version (DD) 25.11.2001 94,90 € 50005931 Ace Wo Nerae Vol. -

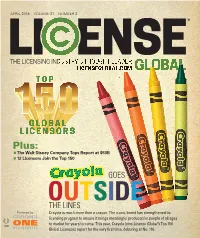

Top 150 Global Licensors Report for the Very First Time, Debuting at No

APRIL 2018 VOLUME 21 NUMBER 2 Plus: The Walt Disney Company Tops Report at $53B 12 Licensors Join the Top 150 GOES OUTSIDE THE LINES Powered by Crayola is much more than a crayon. The iconic brand has strengthened its licensing program to ensure it brings meaningful products for people of all ages to market for years to come. This year, Crayola joins License Global’s Top 150 Global Licensors report for the very first time, debuting at No. 116. WHERE FASHION AND LICENSING MEET The premier resource for licensed fashion, sports, and entertainment accessories. Top 150 Global Licensors GOES OUTSIDE THE LINES Crayola is much more than a crayon. The iconic brand has strengthened its licensing program to ensure it brings meaningful products for people of all ages to market for years to come. This year, Crayola joins License Global’s Top 150 Global Licensors report for the very first time, debuting at No. 116. by PATRICIA DELUCA irst, a word of warning for prospective licensees: Crayola Experience. And with good reason. The Crayola if you wish to do business with Crayola, wear Experience presents the breadth and depth of the comfortable shoes. Initial business won’t be Crayola product world in a way that needs to be seen. Fconducted through a series of email threads or Currently, there are four Experiences in the U.S.– conference calls, instead, all potential partners are asked Minneapolis, Minn.; Orlando, Fla.; Plano, Texas; and Easton, to take a tour of the company’s indoor family attraction, Penn. The latter is where the corporate office is, as well as the nearby Crayola manufacturing facility. -

Lo Natural Y Lo Humano En La Obra De Osamu Tezuka

INTER ASIA PAPERS ISSN 2013-1747 nº 28 / 2012 LO NATURAL Y LO HUMANO EN LA OBRA DE OSAMU TEZUKA. LA CREACIÓN DE TERRITORIOS LITERARIOS ALTERNATIVOS A LA NATURALEZA PERDIDA Maria Antònia Martí Escayol Universitat Autònoma de Barcelon Centro de Estudios e Investigación sobre Asia Oriental Grupo de Investigación Inter Asia Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona INTER ASIA PAPERS © Inter Asia Papers es una publicación conjunta del Centro de Estudios e Investigación sobre Asia Oriental y el Grupo de Investigación Inter Asia de la Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona. CONTACTO EDITORIAL Centro de Estudios e Investigación sobre Asia Oriental Grupo de Investigación Inter Asia Edifici E1 Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona 08193 Bellaterra (Cerdanyola del Vallès) Barcelona España Tel: + 34 - 93 581 2111 Fax: + 34 - 93 581 3266 E-mail: [email protected] Página web: http://www.uab.cat/grup-recerca/interasia © Grupo de Investigación Inter Asia EDITA Centro de Estudios e Investigación sobre Asia Oriental Bellaterra (Cerdanyola del Vallès) Barcelona 2008 Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona ISSN 2013-1739 (versión impresa) Depósito Legal: B-50443-2008 (versión impresa) ISSN 2013-1747 (versión en línea) Depósito Legal: B-50442-2008 (versión en línea) Diseño: Xesco Ortega Lo natural y lo humano en la obra de Osamu Tezuka. La creación de territorios literarios alternativos a la naturaleza perdida Maria Antònia Martí Escayol Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona Resumen El artículo analiza el concepto de naturaleza en la obra del mangaka Osamu Tezuka (1928-1989). En concreto, se examinan los paisajes alternativos construidos argumentalmente en base tanto a la realidad ambiental coetánea del autor como al folklore y a la literatura de ciencia ficción de tradición japonesa. -

Dreamland Japan: Writings on Modern Manga / Frederik L

ederik L. Schodt Writings On Modern Manga V Stone Bridge Press • Berkeley, California Published by Stone Bridge Press, P.O. Box 8208, Berkeley, CA 94707 510-524-8732 • [email protected] • www.stonebridge.com This 2nd printing includes several minor text corrections as well as updates as of 1998/99 for sources and contacts in the Appenidx: Manga in English. Text copyright © 1996 by Frederik L. Schodt. Cover design by Raymond Larrett incorporating an illustration by Yoshikazu Ebisu. Text design by Peter Goodman. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form without permission from the publisher. Printed in the United States of America. 10 98765432 2004 2003 2002 2001 2000 1999 LIBRARY OF CONGRESS CATALOGING-IN-PUBLICATION DATA Schodt, Frederik L. Dreamland Japan: writings on modern manga / Frederik L. Schodt. p. cm. Includes index. ISBN 1 -880656-23-X (paper). 1. Comic books, strips, etc.—Japan— History and criticism. I. Title. PN6790.J3S285 1996 741,5'952—dc20 96-11375 CIP Dedicated to the memory of Kakuyu (aka Toba), A.D. 1053-1140 CONTENTS Preface 11 Enter the Id 19 What Are Manga? 21 Why Read Manga? 29 Modern Manga at the End ■ of the Millennium 33 What's in a Word? 33 The Dojinshi World 36 Otaku 43 Are Manga Dangerous? 49 Freedom of Speech vs. Regulation 53 Black and White Issues # 1 59 Black and White Issues #2 63 Do Manga Have a Future? 68 COVERS OF MANGA MAGAZINES 73 The Manga Magazine Scene 81 CoroCoro Comic 83 Weekly Boys'Jump 87 Nakayoshi 92 Big Comics 95 Morning 101 Tcike Shobo and Mahjong Manga 106 -

Ribon No Kishi (1953-1956): Shōjo Manga E Performatività Di Genere Nel Giappone Postbellico

Corso di Laurea Magistrale in Lingue e Civiltà dell’Asia e dell’Africa Mediterranea ordinamento D.M. 270/2004 Tesi di Laurea Ribon no kishi (1953-1956): shōjo manga e performatività di genere nel Giappone postbellico Relatore Prof. Pierantonio Zanotti Correlatore Prof.ssa Daniela Moro Laureando Cinzia Gioioso Matricola 855716 Anno Accademico 2017/2018 要旨 少女漫画と言ったら抒情画のような花、アンドロジナスな美人のイメージをすぐ思 い出すでしょう。私は子供のころからずっと少女漫画が嫌いでした。つまらなくて浅はか な漫画だと思いました。気に入った少女漫画は一つだけでした、リボンの騎士。小学生の ころに地域チャンネルで放送されたリボンの騎士のアニメを私は見たものでした。 間もなく、リボンの騎士の放送は終了されて、サファイアのことは思い出の中だけ になりました。年を越すと、2011年、漫画学校に通っていた時私はリボンの騎士が私 にとって最初の少女漫画だと気が付きました。子供時代を振り返りました。だが、その時 は大人の観点から王女のことが見えて、サファイアはステレオタイプと異なっていると気 づきました。ですから、この卒業論文でサファイアのジェンダー表象のパターンを調べて 本当にステレオタイプと異なるかどうか理解してみます。 第一章には、この漫画に影響を与えたものを論じました。大変な戦後の間に手塚治 虫が「漫画の神様」と呼ばれて、彼は日本の回復プロセスに携われました。この手塚治虫 の漫画に影響を与えたのは特に宝塚歌劇団と戦前の少女漫画でした。宝塚歌劇団は未婚の 女性だけで構成された歌劇団で、主人公のサファイアは男役として創造されました。男役 というのは男性役を演じる女性です。 第二章では、ストーリーを説明した後、主題の論議を詳細に提示しました。まず、 バトラーのような女権論者研究によるとサファイアがガーリングというプロセスを通じて ヘテロノーマティヴィティに着きます。このプロセス中サファイアのアイデンティティー を知りたい男性の人物からサファイアは視線による暴力を受けるとわかります。後で、パ フォーマンスとパフォーマティヴィティの違いを説明して、主観がヘテロノーマティヴィ ティの論考に頼るとわかります。同様に、少女戦士は家長制度に頼るそうです。 1 最後の章には、服装の重要性を詳細に解説して、サファイアが男役のようなドラグ パフォーマンスを演技するとわかります。そのようなパフォーマンスは、本当の姿でない ことを暴いて、ジェンダーのパロディ観点を明らかにします。それから、両性と中性の区 別を明らかにするためにパッシングという観念を調べた結果はサファイアのパフォーマン スは中性なパフォーマンスだということが分かります。なぜなら、サファイアは男役のよ うに完璧なパッシングをすることができません。さらに、サファイアのアンドロジナスな パフォーマンスをもう一度説明するためにエス関係に属している同一エステティックに触 れます。最後にエディプスコンプレックスを論じてサファイアはどうやってファルスを手 に入れることができるのかを提示します。 ここまでの研究でどうしてリボンの騎士は1970年の漫画の有名な特徴を先んじ ているかを理解できると思います。さて、論文の主な目的はサファイアのジェンダー表象 -

Bearded Collie

BEARDED COLLIE BEARDED COLLIE FCI-GRUPPE: 1 Richter: Oklescen Lidija, SLO Ring: 1 RÜDE - OFFENE KLASSE 1 VISCOUNT BROWN SERA’S OF DOG 4 U, ÖHZB/BC 1852, 30.03.2018, V: PHOENIX BLACK LINDIA’S OF DOG 4 U, M: QUESERA BLACK JAMAICA’S OF DOG 4 U, Z: KEMPF GUDRUN, B: WOLFF THEA RÜDE - VETERANENKLASSE 2 FIRSTPRIZEBEARS KING COLE, LOSH 1101289, 12.10.2011, V: FIRSTPRIZEBEARS HITCHKOCK, M: FIRSTPRIZEBEARS HAVANNA, Z: VERELST H., B: VAN BOSSCHE HEIKE HÜNDIN - JUGENDKLASSE 3 CARO VOM CRÖBERTEICH, VDH/BCCD 2250, 04.11.2019, V: KILTONDALE WASHINGTON, M: AMELIE VOM CRÖBERTEICH, Z: KALLERT INKA UND THOMAS , B: KALLERT INKA UND THOMAS 4 PRAGUE ROXY DE CHESTER, CMKU/BD/3215/-20/19, 27.10.2019, V: SEAGULL LET’S TALK ABOUT IT, M: MARILOU DU DOMAINE DE GOTHAM, Z: BERNARDI UND CLERC, B: JENNEL IVO 5 PALLAS ATHENA DES GARDES CHAMPETRE, LOF 27873, 16.12.2019, V: IRISH COFFEE DES GARDES CHAMPETRE, M: NOUVELLE STAR DU DO- MAINE DE GOTHAM, Z: CAMUS DELPHINE, B: VERNEREY AGNES HÜNDIN - OFFENE KLASSE 6 BLACK MELLIE VOM CRÖBERTEICH, VDH/BCCD 1982, 01.09.2018, V: FIRSTPRIZEBEARS KING COLE, M: OLYMPIA VON DER BRANDEN- BURGER BEARDIE BANDE, Z: KALLERT INKA UND THOMAS, B: KALLERT INKA UND THOMAS HÜNDIN - CHAMPIONKLASSE 7 JUST GLORIA I.E.D. EMIEL REGIS, CMKU/BD/2988/15, 22.05.2015, V: DEA-DRO MARCO POLO, M: FAEINNEWEDD EMIEL REGIS, Z: KONICKOVA HANA / TOKOVA, B: JENNEL IVO 8 AMELIE VOM CRÖBERTEICH, VDH/BCCD 1461, 04.03.2016, V: FIRSTPRIZEBEARS KING COLE, M: OLYMPIA VON DER BRANDEN- BURGER BEARDIE BANDE, Z: KALLERT INKA UND THOMAS , B: KALLERT INKA UND THOMAS 9 ISIS DES -

Ausstellung Messe Kassel

Nationale Rassehunde- Ausstellung Messe Kassel Samstag, 07. Dezember 2019 - 1 - Ausstellungsleitung und Mitarbeiter Veranstalter: VDH-Landesverband Hessen e.V. Mitglied im Verband für das Deutsche Hundewesen (VDH) e.V. Geschäftsstelle Ursula Langer, Am Esch 6 36355 Grebenhain Tel. 06644/820758 Ausstellungs- Elke Gießler leitung: Technische Markus Jakob / Lars Schmidt Leitung: Ehrenring: Tobias Jösch Veterinäraufsicht: Stadt Kassel, Amt für Veterinärdienst und Lebensmittelüberwachung Ausstellungs- Dr. med. vet. Olaf Wappler Tierarzt: Dr. med. vet. Antina Wappler Ärztliche Deutsches Rotes Kreuz Betreuung: Kreisverband Kassel Stadt Kennzeichnung: für Mitarbeiter Identcard mit Angaben der ausgeübten Tätigkeit Tageseinteilung: Samstag, den 7. Dez. 2019 ab 8.00 Uhr Einlass der Hunde 9.00 Uhr Richterbegrüßung ab 9.30 Uhr Bewerten der Hunde - 2 - Nationale Rassehunde-Ausstellung Anwartschaften auf den Titel „Deutscher Champion (VDH)“ „Deutscher Jugendchampion (VDH)“ „Deutscher Veteranen-Champion (VDH)“ Anwartschaften auf das Klub-CAC Veranstalter: VDH Landesverband Hessen e.V. Mitglied im Verband für das Deutsche Hundewesen (VDH) e.V. Sitz Frankfurt am Main Genehmigt: Verband für das Deutsche Hundewesen (VDH) e.V. Schirmherr: Herr Hermann-Josef Klüber Regierungspräsident Samstag, den 7. Dezember 2019 - 3 - INHALTSVERZEICHNIS RASSE Tag Ring-Nr. Kat.-Nr. Affenpinscher ...................................................................... Sa 4 784-785 Afghanen ............................................................................. Sa 43 2968-2988