A Performance and Pedagogical Guide to the Piano Music by Makiko Kinoshita a Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate School in Pa

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

March 21–25, 2016

FORTY-SEVENTH LUNAR AND PLANETARY SCIENCE CONFERENCE PROGRAM OF TECHNICAL SESSIONS MARCH 21–25, 2016 The Woodlands Waterway Marriott Hotel and Convention Center The Woodlands, Texas INSTITUTIONAL SUPPORT Universities Space Research Association Lunar and Planetary Institute National Aeronautics and Space Administration CONFERENCE CO-CHAIRS Stephen Mackwell, Lunar and Planetary Institute Eileen Stansbery, NASA Johnson Space Center PROGRAM COMMITTEE CHAIRS David Draper, NASA Johnson Space Center Walter Kiefer, Lunar and Planetary Institute PROGRAM COMMITTEE P. Doug Archer, NASA Johnson Space Center Nicolas LeCorvec, Lunar and Planetary Institute Katherine Bermingham, University of Maryland Yo Matsubara, Smithsonian Institute Janice Bishop, SETI and NASA Ames Research Center Francis McCubbin, NASA Johnson Space Center Jeremy Boyce, University of California, Los Angeles Andrew Needham, Carnegie Institution of Washington Lisa Danielson, NASA Johnson Space Center Lan-Anh Nguyen, NASA Johnson Space Center Deepak Dhingra, University of Idaho Paul Niles, NASA Johnson Space Center Stephen Elardo, Carnegie Institution of Washington Dorothy Oehler, NASA Johnson Space Center Marc Fries, NASA Johnson Space Center D. Alex Patthoff, Jet Propulsion Laboratory Cyrena Goodrich, Lunar and Planetary Institute Elizabeth Rampe, Aerodyne Industries, Jacobs JETS at John Gruener, NASA Johnson Space Center NASA Johnson Space Center Justin Hagerty, U.S. Geological Survey Carol Raymond, Jet Propulsion Laboratory Lindsay Hays, Jet Propulsion Laboratory Paul Schenk, -

Emily Dickinson in Song

1 Emily Dickinson in Song A Discography, 1925-2019 Compiled by Georgiana Strickland 2 Copyright © 2019 by Georgiana W. Strickland All rights reserved 3 What would the Dower be Had I the Art to stun myself With Bolts of Melody! Emily Dickinson 4 Contents Preface 5 Introduction 7 I. Recordings with Vocal Works by a Single Composer 9 Alphabetical by composer II. Compilations: Recordings with Vocal Works by Multiple Composers 54 Alphabetical by record title III. Recordings with Non-Vocal Works 72 Alphabetical by composer or record title IV: Recordings with Works in Miscellaneous Formats 76 Alphabetical by composer or record title Sources 81 Acknowledgments 83 5 Preface The American poet Emily Dickinson (1830-1886), unknown in her lifetime, is today revered by poets and poetry lovers throughout the world, and her revolutionary poetic style has been widely influential. Yet her equally wide influence on the world of music was largely unrecognized until 1992, when the late Carlton Lowenberg published his groundbreaking study Musicians Wrestle Everywhere: Emily Dickinson and Music (Fallen Leaf Press), an examination of Dickinson's involvement in the music of her time, and a "detailed inventory" of 1,615 musical settings of her poems. The result is a survey of an important segment of twentieth-century music. In the years since Lowenberg's inventory appeared, the number of Dickinson settings is estimated to have more than doubled, and a large number of them have been performed and recorded. One critic has described Dickinson as "the darling of modern composers."1 The intriguing question of why this should be so has been answered in many ways by composers and others. -

Fuji-Ya, Second to None Reiko Weston’S Role in Reconnecting Minneapolis and the Mississippi River

Fuji-Ya, Second to None Reiko Weston’s Role in Reconnecting Minneapolis and the Mississippi River Kimmy Tanaka and Jonathan Moore end of the bridge is a large boulder Nearly three centuries later, with a plaque affixed to it. The plaque another explorer would arrive at ore than two million people recounts the discovery of St. Anthony the opposite end of the bridge and annually cross the Stone Falls by a Franciscan priest, Father behold the place with new eyes. Her M Arch Bridge over the Mis- Louis Hennepin, who first viewed the name was Reiko Umetani Weston. sissippi River at St. Anthony Falls, falls in 1680 and named them for his While Weston introduced many drawn to the history and vibrancy of patron saint, St. Anthony of Padua.1 Minnesotans to Japanese cuisine and the sublime setting. There is the roar There is, of course, more to the culture for the first time through of the falls that can be heard before it story. People knew of the falls prior to her Fuji- Ya restaurant, arguably her can be seen. There are the waves and Father Hennepin’s visit, and it already greatest influence was connecting white foam of the water as it passes had a name— several, in fact. To the a city to its river once again. The over the spillway and crashes on the Dakota, who had guided the priest to restaurant’s physical embodiment— dissipaters below. There is the min- this location, it was called Owamni three solid walls to the city with one eral smell of the mist that is thrust Omni (whirlpool). -

The Literary Landscape of Murakami Haruki

Akins, Midori Tanaka (2012) Time and space reconsidered: the literary landscape of Murakami Haruki. PhD Thesis. SOAS, University of London http://eprints.soas.ac.uk/15631 Copyright © and Moral Rights for this thesis are retained by the author and/or other copyright owners. A copy can be downloaded for personal non‐commercial research or study, without prior permission or charge. This thesis cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the copyright holder/s. The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. When referring to this thesis, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given e.g. AUTHOR (year of submission) "Full thesis title", name of the School or Department, PhD Thesis, pagination. Time and Space Reconsidered: The Literary Landscape of Murakami Haruki Midori Tanaka Atkins Thesis submitted for the degree of PhD in Japanese Literature 2012 Department of Languages & Cultures School of Oriental and African Studies University of London Declaration for PhD thesis I have read and understood regulation 17.9 of the Regulations for students of the School of Oriental and African Studies concerning plagiarism. I undertake that all the material presented for examination is my own work and has not been written for me, in whole or in part, by any other person. I also undertake that any quotation or paraphrase from the published or unpublished work of another person has been duly acknowledged in the work which I present for examination. -

Explorations 2005 MECC’S Arts E-Zine

Explorations 2005 MECC’s Arts E-Zine The originality, creativity, technical skill, and enormous artistic vitality represented in these pages are something to be proud of. We hope that everyone will enjoy and appreciate the talents displayed. We especially want to thank all the students and alumni who entered the competition, and all of the people on campus in Student Services, the Wampler Library, and the staff of the Public Relations office who make this competition and the publication possible. WELCOME to Explorations, Mountain Empire Community College’s student arts publication. Current and former students were invited to submit work in the categories of poetry, short stories, personal essays, black and white photography, color photography, drawing and painting. The materials recognized by our judges in each category are featured. Photography MORRIS BURCHETTE, owner of Burchette Photography in Norton, became interested in photography when he was nine years old and has been in business in Norton for 54 years. A long- standing member of the Professional Photographers of America, he has won many awards of his own, including the prestigious Master of Photography degree from that organization. Poetry RICHARD HAGUE, now retired from public school teaching in Cincinnati, Ohio, is the author of five full-length poetry collections, including Possible Debris, from the Cleveland State Poetry Center, and Milltown Natural: Essays and Stories from a Life, from Bottom Dog Press, which was a finalist for Association Writing Programs Award in Creative Nonfiction and nominated for the National Book Award. Short Story TAMARA BAXTER teaches at Northeast State Community College in Blountville, Tennessee. -

Anime/Games/J-Pop/J-Rock/Vocaloid

Anime/Games/J-Pop/J-Rock/Vocaloid Deutsch Alice Im Wunderland Opening Anne mit den roten Haaren Opening Attack On Titans So Ist Es Immer Beyblade Opening Biene Maja Opening Catpain Harlock Opening Card Captor Sakura Ending Chibi Maruko-Chan Opening Cutie Honey Opening Detektiv Conan OP 7 - Die Zeit steht still Detektiv Conan OP 8 - Ich Kann Nichts Dagegen Tun Detektiv Conan Opening 1 - 100 Jahre Geh'n Vorbei Detektiv Conan Opening 2 - Laufe Durch Die Zeit Detektiv Conan Opening 3 - Mit Aller Kraft Detektiv Conan Opening 4 - Mein Geheimnis Detektiv Conan Opening 5 - Die Liebe Kann Nicht Warten Die Tollen Fussball-Stars (Tsubasa) Opening Digimon Adventure Opening - Leb' Deinen Traum Digimon Adventure Opening - Leb' Deinen Traum (Instrumental) Digimon Adventure Wir Werden Siegen (Instrumental) Digimon Adventure 02 Opening - Ich Werde Da Sein Digimon Adventure 02 Opening - Ich Werde Da Sein (Insttrumental) Digimon Frontier Die Hyper Spirit Digitation (Instrumental) Digimon Frontier Opening - Wenn das Feuer In Dir Brennt Digimon Frontier Opening - Wenn das Feuer In Dir Brennt (Instrumental) (Lange Version) Digimon Frontier Wenn Du Willst (Instrumental) Digimon Tamers Eine Vision (Instrumental) Digimon Tamers Ending - Neuer Morgen Digimon Tamers Neuer Morgen (Instrumental) Digimon Tamers Opening - Der Grösste Träumer Digimon Tamers Opening - Der Grösste Träumer (Instrumental) Digimon Tamers Regenbogen Digimon Tamers Regenbogen (Instrumental) Digimon Tamers Sei Frei (Instrumental) Digimon Tamers Spiel Dein Spiel (Instrumental) DoReMi Ending Doremi -

Commencement 2001-2005

THE JOHNS HOPKINS UNIVERSITY TWO THOUSAND TWO COMMENCEMENT Conferring of Degrees at the Close of the 126th Academic Year Class of 2002 May 23, 2002 9:15 a.m. —— — —— 67 — — ———— — Candidates Seating Stage 8 11 10 12 13 14 15 16 17 19 18 I Doctors of Philosophy and 2 Doctors of Philosophy Arts and Sciences and Doctors of Medicine Medicine Engineering 3 Doctors of Philosophy, Doctors of Public Health, 4 Doctors of Philosophy Advanced International and Doctors of Science Public Health Studies 5 Masters Medicine 6 Doctors of Philosophy—Nursing 9 Masters Public Health 7 Doctors of Musical Arts and Artist Diplomas Peabody I I Certificates of Advanced Graduate Study and Masters Professional Studies in Business 8 Doctors of Education Professional Studies in and Education Business and Education 1 3 Bachelors Professional Studies in Business 1 Masters Arts and Sciences and Education 1 2 Masters and Certificates Engineering 1 5 Bachelors Engineering 14 Masters and Bachelors Nursing 19 Bachelors (A-F) Arts and Sciences 1 Masters, Certificates, and Bachelors Peabody 1 Masters Advanced International Studies 18 Bachelors (G-Z) Arts and Sciences Contents Order of Procession 1 Order of Events 2 Divisional Diploma Ceremonies Information 6 Johns Hopkins Society of Scholars 7 Honorary Degree Citations 11 Academic Regalia 14 Awards 16 Honor Societies 22 Honors 25 Candidates for Degrees 30 wmQg&m<si$5m/:: Please note that while all degrees are conferred, only doctoral graduates process across the stage. Though taking photos from your seats during the ceremonj is not prohibited, we request that guests respect each other's comfort and enjoyment by not standing and blocking other people's views. -

Confectionery

Confectionery Alpen Chocolate & Caramel Alpen Fruit & Nut Milk Choc Alpen Light Banoffee Cereal Alpen Light Cherry Bakewell Cereal Bars 5 Pack Tesco Cereal Bars 5 Pack Tes Bars 5pk Tesco £1.99 # Cereal Bars 5pk Tesco 10X 300056 10X 300057 10X 300058 10X 300059 Alpen Light Double Choc Alpen Light Jaffa Bars 5 Pack Alpen Light Summerfruits Alpen Raspberry & Yogurt Cereal Bars 5 Pack Tesco £ Tesco £1.99 #2 95g ( Cereal Bar 5 Pk Tesco £1. Cereal Bar 5 Pk Tesco £1. 10X 300062 10X 300060 10X 300061 10X 300063 Alpen Strawberry & Yogurt Barratt Fruit Salad Softies PM Barratt Nougat Bars 4pk RRP Barratt Refresher Softies PM Cereal Bar 5 Pk Tesco £1 £1 120g £1.29 140g (Q) £1 120g 10X 300064 12X 300381 12X 300349 12X 300382 Confectionery Bassetts Everton Mints Bag Bassetts Jelly Babies Bag PM Bassetts Jelly Bunnies Bag Bassetts Liquorice Allsorts Sainsburys £1.50 192g £1 165g RRP£1.32 165g PM £1 165g 12X 301403 12X 300438 12X 300619 12X 300008 Bassetts Mint Favourites Bassetts Mint Imperials Bag Bassetts Murray Mints Bags Bassetts Sherbet Lemons Bags Sainsburys £1.50 19 Sainsburys £1.50 200g Sainsburys £1.50 193g Bag Sainsburys £1.50 192g 12X 301402 12X 301404 12X 301401 12X 301405 Bazooka Big Baby Pop PM Bazooka Bubblegum 6 piece Bazooka Flip n Dip Push Pop Bazooka Juicy Drop 85p 32g Wallet RRP 40p 33g RRP £1.25 25g Gummies RRP £1.19 57g 12X 301325 12X 301323 12X 301327 12X 301326 Confectionery Bazooka Juicy Drop Pop PM Bazooka Mega Mouth Spray Bazooka Push Pop 3 pack Bazooka Push Pop PM 50p 99p 26g PM 95p 23g RRP £1.49 45g 26g 12X 301319 12X 301321 -

Strawbs Lemon Pie Mp3, Flac, Wma

Strawbs Lemon Pie mp3, flac, wma DOWNLOAD LINKS (Clickable) Genre: Rock Album: Lemon Pie Country: UK Released: 1975 Style: Prog Rock MP3 version RAR size: 1319 mb FLAC version RAR size: 1313 mb WMA version RAR size: 1955 mb Rating: 4.6 Votes: 487 Other Formats: MP4 WAV AUD VQF FLAC WMA DTS Tracklist Hide Credits Lemon Pie A 3:10 Written-By – Cousins* Don't Try To Change Me B 4:28 Written-By – Lambert* Companies, etc. Phonographic Copyright (p) – A&M Records Ltd. Recorded By – A&M Records Ltd. Published By – Summerland Songs Ltd. Published By – Arnakata Music Ltd. Credits Producer – Tom Allom Notes From the A & M album Ghosts AMLH 68277 Publishers Summerland Songs Ltd (track A) Arnakata Music Ltd (track B) Barcode and Other Identifiers Matrix / Runout (Runout A [stamped]): AMS-7161-A1 Matrix / Runout (Runout B [stamped]): AMS-7161-B1 Matrix / Runout (Runout B [etched]): DAFI Matrix / Runout (Label A): AMS 7161-A Matrix / Runout (Label B): AMS 7161-B Other (Labels A+B): Not for sale Other versions Category Artist Title (Format) Label Category Country Year AMS 7161 Strawbs Lemon Pie (7") A&M Records AMS 7161 UK 1975 Lemon Pie / Where Do You Go 1687 Strawbs (When You Need A Hole To A&M Records 1687 Canada 1975 Crawl In) (7", Promo) K-5924 Strawbs Lemon Pie (7", Single) A&M Records K-5924 New Zealand 1975 K-5924 Strawbs Lemon Pie (7", Single) A&M Records K-5924 Australia 1975 Lemon Pie / Where Do You Go 1687-S Strawbs (When You Need A Hole To A&M Records 1687-S US 1975 Crawl In) (7", Promo) Related Music albums to Lemon Pie by Strawbs Rock / Folk, World, & Country The Strawbs - Or Am I Dreaming / Oh, How She Changed Electronic Lemon Popsicle - Lemon Delite Electronic Kinky Machine - Going Out With God Rock Strawbs - Grave New World Rock Lemon Avenue - Axeman Rock Strawbs - Deep Cuts Rock Strawbs - Ghosts Rock Judas Priest - Breaking The Law Folk, World, & Country Καίτη Γκρέυ - Όταν Ακούω Καζαντζίδη Reggae The Wailers - Lemon Tree. -

Country Women Piracy Gambit

$6.95 (U.S.), $8.95 (CAN.), £5.50 (U.K.), 8.95 (EUROPE), Y2,500 (JAPAN) aw CL V) W z HI CCVR H 3 -DIGIT 9011 'IIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIII I IIIIIII #90807GEE374EM002# BLBD 893 A06 B0093 001 MAR 04 2 MONTY GREENLY 3740 ELM AVE # A LONG BEACH CA 90807 -3402 111 UMW r THE INTERNATIONAL NEWSWEEKLY OF MUSIC, VIDEO AND HOME ENTERTAINMENT www.billboard.com JULY 5, 2003 Shal aTwzin at the HOT SPOTS recent Country Music Aw r Is. The Mercury Piracy Gambit artist is the lone female with a current top 10 country single. Raises Stakes RIAA Lawsuit Strategy Risks Consumer Backlash BY BILL HOLLAND and BRIAN GARRITY WASHINGTON, D.C.-The music 5 'Phoenix Rising industry's promised blitzkreig of law- suits against Internet song swappers- The new "Marry Potter and the including file-sharing teens-could Order of the Phoenix" flies out quickly become a legal quagmire. of retail outlets in record num- some critics warn. bers: 5 m Ilion in 24 hours. But with frustration levels running high after months of fruitless educa- tional campaigns, the industry is hell- bent on raising the stakes in the war on music pirates. As it launched its newest offensive June 25, the industry picked up a major ally in Congress. Rep. Lamar Smith, R- Texas, the anti -piracy cham- (Continued on page 74) Majors' Woes Continue 5 Jam On It Country Women Gov't Mule's Warren Haynes is Talks among the artists helping Along With Merger this summer's hot jam band Lose Hit Magic BY MATTHEW BENZ tour to jell. -

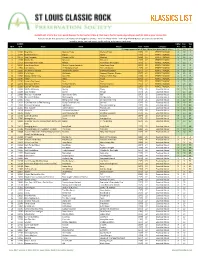

KLASSICS LIST Criteria

KLASSICS LIST criteria: 8 or more points (two per fan list, two for U-Man A-Z list, two to five for Top 95, depending on quartile); 1984 or prior release date Sources: ten fan lists (online and otherwise; see last page for details) + 2011-12 U-Man A-Z list + 2014 Top 95 KSHE Klassics (as voted on by listeners) sorted by points, Fan Lists count, Top 95 ranking, artist name, track name SLCRPS UMan Fan Top ID # ID # Track Artist Album Year Points Category A-Z Lists 95 35 songs appeared on all lists, these have green count info >> X 10 n 1 12404 Blue Mist Mama's Pride Mama's Pride 1975 27 PERFECT KLASSIC X 10 1 2 12299 Dead And Gone Gypsy Gypsy 1970 27 PERFECT KLASSIC X 10 2 3 11672 Two Hangmen Mason Proffit Wanted 1969 27 PERFECT KLASSIC X 10 5 4 11578 Movin' On Missouri Missouri 1977 27 PERFECT KLASSIC X 10 6 5 11717 Remember the Future Nektar Remember the Future 1973 27 PERFECT KLASSIC X 10 7 6 10024 Lake Shore Drive Aliotta Haynes Jeremiah Lake Shore Drive 1971 27 PERFECT KLASSIC X 10 9 7 11654 Last Illusion J.F. Murphy & Salt The Last Illusion 1973 27 PERFECT KLASSIC X 10 12 8 13195 The Martian Boogie Brownsville Station Brownsville Station 1977 27 PERFECT KLASSIC X 10 13 9 13202 Fly At Night Chilliwack Dreams, Dreams, Dreams 1977 27 PERFECT KLASSIC X 10 14 10 11696 Mama Let Him Play Doucette Mama Let Him Play 1978 27 PERFECT KLASSIC X 10 15 11 11547 Tower Angel Angel 1975 27 PERFECT KLASSIC X 10 19 12 11730 From A Dry Camel Dust Dust 1971 27 PERFECT KLASSIC X 10 20 13 12131 Rosewood Bitters Michael Stanley Michael Stanley 1972 27 PERFECT -

Strawbs the Collection Mp3, Flac, Wma

Strawbs The Collection mp3, flac, wma DOWNLOAD LINKS (Clickable) Genre: Rock / Blues / Folk, World, & Country Album: The Collection Country: Europe Style: Folk Rock MP3 version RAR size: 1468 mb FLAC version RAR size: 1304 mb WMA version RAR size: 1705 mb Rating: 4.6 Votes: 657 Other Formats: DTS MP4 MMF MIDI AAC TTA AA Tracklist Hide Credits Part Of The Union 1 Written-By – Ford*, Hudson* I'll Carry On Beside You 2 Written-By – Cousins* The Man Who Called Himself Jesus 3 Written-By – Cousins* Oh How She Changed 4 Written-By – Cousins* I Turned My Face Into The Wind 5 Written-By – Cousins* Song Of A Sad Little Girl 6 Written-By – Cousins* Witchwood 7 Written-By – Cousins* Benedictus 8 Written-By – Cousins* Heavy Disguise 9 Written-By – Ford* Keep The DevilOutside 10 Written-By – Ford* Shine On Silver Sun 11 Written-By – Cousins* Grace Darling 12 Written-By – Cousins* Lemon Pie 13 Written-By – Cousins* Martin Luther King's Dream 14 Written-By – Cousins* Tokyo Rose 15 Written-By – Cousins* Willl You Go 16 Written-By – McPeake* I Only Want My Love To Grow In You 17 Written-By – Cronk*, Cousins* Lay Down 18 Written-By – Cousins* Companies, etc. Phonographic Copyright (p) – Spectrum Music Phonographic Copyright (p) – A&M Records, Inc. Phonographic Copyright (p) – Strawbs Ltd. Copyright (c) – Spectrum Music Licensed From – A&M Records, Inc. Published By – Arnakata Music Inc. Published By – Irving Music, Inc. Published By – Old School Songs Published By – SGO Music Publishing Ltd. Published By – Fazz Music Published By – Chappell Music Ltd.