Innovation and Reform of the Hammered Dulcimer Yangqinin Contemporary China

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Liste Représentative Du Patrimoine Culturel Immatériel De L'humanité

Liste représentative du patrimoine culturel immatériel de l’humanité Date de Date récente proclamation Intitulé officiel Pays d’inscriptio Référence ou première n inscription Al-Ayyala, un art traditionnel du Oman - Émirats spectacle dans le Sultanat d’Oman et 2014 2014 01012 arabes unis aux Émirats arabes unis Al-Zajal, poésie déclamée ou chantée Liban 2014 2014 01000 L’art et le symbolisme traditionnels du kelaghayi, fabrication et port de foulards Azerbaïdjan 2014 2014 00669 en soie pour les femmes L’art traditionnel kazakh du dombra kuï Kazakhstan 2014 2014 00011 L’askiya, l’art de la plaisanterie Ouzbékistan 2014 2014 00011 Le baile chino Chili 2014 2014 00988 Bosnie- La broderie de Zmijanje 2014 2014 00990 Herzégovine Le cante alentejano, chant polyphonique Portugal 2014 2014 01007 de l’Alentejo (sud du Portugal) Le cercle de capoeira Brésil 2014 2014 00892 Le chant traditionnel Arirang dans la République 2014 2014 00914 République populaire démocratique de populaire Date de Date récente proclamation Intitulé officiel Pays d’inscriptio Référence ou première n inscription Corée démocratique de Corée Les chants populaires ví et giặm de Viet Nam 2014 2014 01008 Nghệ Tĩnh Connaissances et savoir-faire traditionnels liés à la fabrication des Kazakhstan - 2014 2014 00998 yourtes kirghizes et kazakhes (habitat Kirghizistan nomade des peuples turciques) La danse rituelle au tambour royal Burundi 2014 2014 00989 Ebru, l’art turc du papier marbré Turquie 2014 2014 00644 La fabrication artisanale traditionnelle d’ustensiles en laiton et en -

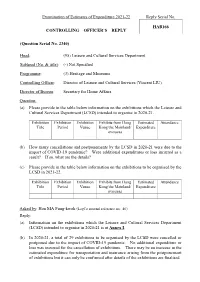

Examination of Estimates of Expenditure 2021-22 Reply Serial No

Examination of Estimates of Expenditure 2021-22 Reply Serial No. HAB166 CONTROLLING OFFICER’S REPLY (Question Serial No. 2340) Head: (95) Leisure and Cultural Services Department Subhead (No. & title): (-) Not Specified Programme: (3) Heritage and Museums Controlling Officer: Director of Leisure and Cultural Services (Vincent LIU) Director of Bureau: Secretary for Home Affairs Question: (a) Please provide in the table below information on the exhibitions which the Leisure and Cultural Services Department (LCSD) intended to organise in 2020-21. Exhibition Exhibition Exhibition Exhibits from Hong Estimated Attendance Title Period Venue Kong/the Mainland/ Expenditure overseas (b) How many cancellations and postponements by the LCSD in 2020-21 were due to the impact of COVID-19 pandemic? Were additional expenditures or loss incurred as a result? If so, what are the details? (c) Please provide in the table below information on the exhibitions to be organised by the LCSD in 2021-22. Exhibition Exhibition Exhibition Exhibits from Hong Estimated Attendance Title Period Venue Kong/the Mainland/ Expenditure overseas Asked by: Hon MA Fung-kwok (LegCo internal reference no.: 46) Reply: (a) Information on the exhibitions which the Leisure and Cultural Services Department (LCSD) intended to organise in 2020-21 is at Annex I. (b) In 2020-21, a total of 29 exhibitions to be organised by the LCSD were cancelled or postponed due to the impact of COVID-19 pandemic. No additional expenditure or loss was incurred for the cancellation of exhibitions. There may be an increase in the estimated expenditure for transportation and insurance arising from the postponement of exhibitions but it can only be confirmed after details of the exhibitions are finalised. -

The Ukrainian Weekly 2001, No.16

www.ukrweekly.com INSIDE: • “CHORNOBYL: THE FIFTEENTH ANNIVERSARY” Special section — pages 4-10. Published by the Ukrainian National Association Inc., a fraternal non-profit association Vol. LXIX No. 16 THE UKRAINIAN WEEKLY SUNDAY, APRIL 22, 2001 $1/$2 in Ukraine HE YuschenkoKRAINIAN government hangsEEKLY on, for now U.S.T grants asylum U W by Roman Woronowycz Rada, which last week submitted 237 law- Kyiv Press Bureau makers’ signatures in support of the propos- to Melnychenko, al. A simple majority of 226 signatures was KYIV – The government of Victor needed to table the proposal. The parlia- Yuschenko was left hanging by a thread on mentary session accepted the motion on Myroslava Gongadze April 19 after Ukraine’s Parliament voted in April 17 prior to a report by Prime Minister by Roman Woronowycz support of a resolution criticizing the work Yuschenko on the progress made in 2000 Kyiv Press Bureau of his Cabinet in 2000 as unsatisfactory. on implementation of the government’s The lawmakers decided to schedule a vote KYIV – The wife of Heorhii Gongadze, economic revival plan, called “Reforms for on a motion of no confidence within a the missing journalist feared dead who is at Well-Being.” week, which if passed would lead automati- the center of a huge political crisis in Kyiv, The Social Democrats (United), Labor and a former presidential bodyguard who cally to the dissolution of the government. Ukraine and the Democratic Union are con- produced tape recordings that seemingly The stormy session was marked by a sidered the bastions of the business oli- implicate the president in the disappearance near tragedy as National Deputy Lilia garchs and are led respectively, by Viktor have received political asylum in the United Hryhorovych of the Rukh faction doused Medvedchuk, Viktor Pinchuk and States, revealed the U.S. -

The Science of String Instruments

The Science of String Instruments Thomas D. Rossing Editor The Science of String Instruments Editor Thomas D. Rossing Stanford University Center for Computer Research in Music and Acoustics (CCRMA) Stanford, CA 94302-8180, USA [email protected] ISBN 978-1-4419-7109-8 e-ISBN 978-1-4419-7110-4 DOI 10.1007/978-1-4419-7110-4 Springer New York Dordrecht Heidelberg London # Springer Science+Business Media, LLC 2010 All rights reserved. This work may not be translated or copied in whole or in part without the written permission of the publisher (Springer Science+Business Media, LLC, 233 Spring Street, New York, NY 10013, USA), except for brief excerpts in connection with reviews or scholarly analysis. Use in connection with any form of information storage and retrieval, electronic adaptation, computer software, or by similar or dissimilar methodology now known or hereafter developed is forbidden. The use in this publication of trade names, trademarks, service marks, and similar terms, even if they are not identified as such, is not to be taken as an expression of opinion as to whether or not they are subject to proprietary rights. Printed on acid-free paper Springer is part of Springer ScienceþBusiness Media (www.springer.com) Contents 1 Introduction............................................................... 1 Thomas D. Rossing 2 Plucked Strings ........................................................... 11 Thomas D. Rossing 3 Guitars and Lutes ........................................................ 19 Thomas D. Rossing and Graham Caldersmith 4 Portuguese Guitar ........................................................ 47 Octavio Inacio 5 Banjo ...................................................................... 59 James Rae 6 Mandolin Family Instruments........................................... 77 David J. Cohen and Thomas D. Rossing 7 Psalteries and Zithers .................................................... 99 Andres Peekna and Thomas D. -

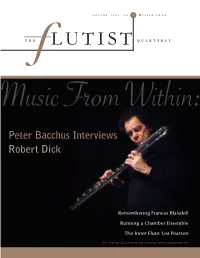

The Flutist Quarterly Volume Xxxv, N O

VOLUME XXXV , NO . 2 W INTER 2010 THE LUTI ST QUARTERLY Music From Within: Peter Bacchus Interviews Robert Dick Remembering Frances Blaisdell Running a Chamber Ensemble The Inner Flute: Lea Pearson THE OFFICIAL MAGAZINE OF THE NATIONAL FLUTE ASSOCIATION , INC :ME:G>:C8: I=: 7DA9 C:L =:69?D>CI ;GDB E:6GA 6 8ji 6WdkZ i]Z GZhi### I]Z cZl 8Vadg ^h EZVgaÉh bdhi gZhedch^kZ VcY ÓZm^WaZ ]ZVY_d^ci ZkZg XgZViZY# Djg XgV[ihbZc ^c ?VeVc ]VkZ YZh^\cZY V eZg[ZXi WaZcY d[ edlZg[ja idcZ! Z[[dgiaZhh Vgi^XjaVi^dc VcY ZmXZei^dcVa YncVb^X gVc\Z ^c dcZ ]ZVY_d^ci i]Vi ^h h^bean V _dn id eaVn# LZ ^ck^iZ ndj id ign EZVgaÉh cZl 8Vadg ]ZVY_d^ci VcY ZmeZg^ZcXZ V cZl aZkZa d[ jcbViX]ZY eZg[dgbVcXZ# EZVga 8dgedgVi^dc *). BZigdeaZm 9g^kZ CVh]k^aaZ! IC (,'&& -%%".),"(',* l l l # e Z V g a [ a j i Z h # X d b Table of CONTENTS THE FLUTIST QUARTERLY VOLUME XXXV, N O. 2 W INTER 2010 DEPARTMENTS 5 From the Chair 51 Notes from Around the World 7 From the Editor 53 From the Program Chair 10 High Notes 54 New Products 56 Reviews 14 Flute Shots 64 NFA Office, Coordinators, 39 The Inner Flute Committee Chairs 47 Across the Miles 66 Index of Advertisers 16 FEATURES 16 Music From Within: An Interview with Robert Dick by Peter Bacchus This year the composer/musician/teacher celebrates his 60th birthday. Here he discusses his training and the nature of pedagogy and improvisation with composer and flutist Peter Bacchus. -

A Review of the Origin and Evolution of Uygur Musical Instruments

2019 International Conference on Humanities, Cultures, Arts and Design (ICHCAD 2019) A Review of the Origin and Evolution of Uygur Musical Instruments Xiaoling Wang, Xiaoling Wu Changji University Changji, Xinjiang, China Keywords: Uygur Musical Instruments, Origin, Evolution, Research Status Abstract: There Are Three Opinions about the Origin of Uygur Musical Instruments, and Four Opinions Should Be Exact. Due to Transliteration, the Same Musical Instrument Has Multiple Names, Which Makes It More Difficult to Study. So Far, the Origin of Some Musical Instruments is Difficult to Form a Conclusion, Which Needs to Be Further Explored by People with Lofty Ideals. 1. Introduction Uyghur Musical Instruments Have Various Origins and Clear Evolution Stages, But the Process is More Complex. I Think There Are Four Sources of Uygur Musical Instruments. One is the National Instrument, Two Are the Central Plains Instruments, Three Are Western Instruments, Four Are Indigenous Instruments. There Are Three Changes in the Development of Uygur Musical Instruments. Before the 10th Century, the Main Musical Instruments Were Reed Flute, Flute, Flute, Suona, Bronze Horn, Shell, Pottery Flute, Harp, Phoenix Head Harp, Kojixiang Pipa, Wuxian, Ruan Xian, Ruan Pipa, Cymbals, Bangling Bells, Pan, Hand Drum, Iron Drum, Waist Drum, Jiegu, Jilou Drum. At the Beginning of the 10th Century, on the Basis of the Original Instruments, Sattar, Tanbu, Rehwap, Aisi, Etc New Instruments Such as Thar, Zheng and Kalong. after the Middle of the 20th Century, There Were More Than 20 Kinds of Commonly Used Musical Instruments, Including Sattar, Trable, Jewap, Asitar, Kalong, Czech Republic, Utar, Nyi, Sunai, Kanai, Sapai, Balaman, Dapu, Narre, Sabai and Kashtahi (Dui Shi, or Chahchak), Which Can Be Divided into Four Categories: Choral, Membranous, Qiming and Ti Ming. -

Off the Beaten Track

Off the Beaten Track To have your recording considered for review in Sing Out!, please submit two copies (one for one of our reviewers and one for in- house editorial work, song selection for the magazine and eventual inclusion in the Sing Out! Resource Center). All recordings received are included in “Publication Noted” (which follows “Off the Beaten Track”). Send two copies of your recording, and the appropriate background material, to Sing Out!, P.O. Box 5460 (for shipping: 512 E. Fourth St.), Bethlehem, PA 18015, Attention “Off The Beaten Track.” Sincere thanks to this issue’s panel of musical experts: Richard Dorsett, Tom Druckenmiller, Mark Greenberg, Victor K. Heyman, Stephanie P. Ledgin, John Lupton, Angela Page, Mike Regenstreif, Seth Rogovoy, Ken Roseman, Peter Spencer, Michael Tearson, Theodoros Toskos, Rich Warren, Matt Watroba, Rob Weir and Sule Greg Wilson. that led to a career traveling across coun- the two keyboard instruments. How I try as “The Singing Troubadour.” He per- would have loved to hear some of the more formed in a variety of settings with a rep- unusual groupings of instruments as pic- ertoire that ranged from opera to traditional tured in the notes. The sound of saxo- songs. He also began an investigation of phones, trumpets, violins and cellos must the music of various utopian societies in have been glorious! The singing is strong America. and sincere with nary a hint of sophistica- With his investigation of the music of tion, as of course it should be, as the Shak- VARIOUS the Shakers he found a sect which both ers were hardly ostentatious. -

(WKCD) Development M+ in West Kowloon Cultural District

WKCD-546 Legislative Council Subcommittee on West Kowloon Cultural District (WKCD) Development M+ in West Kowloon Cultural District Purpose This paper seeks to give a full account of the proposal to develop a forward-looking cultural institution with museum functions - M+ as a core arts and cultural facility in the West Kowloon Cultural District (“WKCD”). Background 2. In September 2003, the Government launched the “Invitation for Proposals” (“IFP”) for developing WKCD as a world-class arts, cultural, entertainment and commercial district. The IFP had specified a cluster of four museums with four themes (moving image, modern art, ink and design) commanding a total Net Operating Floor Area (“NOFA”) of at least 75 000 m², and an art exhibition centre as Mandatory Requirements of the project. 3. After the IFP for WKCD was discontinued, the Government appointed the Museums Advisory Group (“MAG”) under the Consultative Committee on Core Arts and Cultural Facilities of WKCD in April 2006 to advise on the need for the four museums previously proposed and their preferred themes, the need to include museums with other themes, the scale and major requirements of each museum and the need for and major specifications of the Art Exhibition Centre. MAG’s deliberations process 4. The MAG conducted a public consultation exercise from mid-May to mid-June 2006 to solicit views on the proposed museum in WKCD. During the period, two open public forums, one focus group meeting and three presentation hearings were held apart from wide publicity arranged through advertisements, radio announcements, press release and invitation letters. 28 written submissions and 30 views were received during the consultation period. -

Three Millennia of Tonewood Knowledge in Chinese Guqin Tradition: Science, Culture, Value, and Relevance for Western Lutherie

Savart Journal Article 1 Three millennia of tonewood knowledge in Chinese guqin tradition: science, culture, value, and relevance for Western lutherie WENJIE CAI1,2 AND HWAN-CHING TAI3 Abstract—The qin, also called guqin, is the most highly valued musical instrument in the culture of Chinese literati. Chinese people have been making guqin for over three thousand years, accumulating much lutherie knowledge under this uninterrupted tradition. In addition to being rare antiques and symbolic cultural objects, it is also widely believed that the sound of Chinese guqin improves gradually with age, maturing over hundreds of years. As such, the status and value of antique guqin in Chinese culture are comparable to those of antique Italian violins in Western culture. For guqin, the supposed acoustic improvement is generally attributed to the effects of wood aging. Ancient Chinese scholars have long discussed how and why aging improves the tone. When aged tonewood was not available, they resorted to various artificial means to accelerate wood aging, including chemical treatments. The cumulative experience of Chinese guqin makers represent a valuable source of tonewood knowledge, because they give us important clues on how to investigate long-term wood changes using modern research tools. In this review, we translated and annotated tonewood knowledge in ancient Chinese books, comparing them with conventional tonewood knowledge in Europe and recent scientific research. This retrospective analysis hopes to highlight the practical value of Chinese lutherie knowledge for 21st-century instrument makers. I. INTRODUCTION In Western musical tradition, the most valuable musical instruments belong to the violin family, especially antique instruments made in Cremona, Italy. -

2018 Available in Carbon Fibre

NFAc_Obsession_18_Ad_1.pdf 1 6/4/18 3:56 PM Brannen & LaFIn Come see how fast your obsession can begin. C M Y CM MY CY CMY K Booth 301 · brannenutes.com Brannen Brothers Flutemakers, Inc. HANDMADE CUSTOM 18K ROSE GOLD TRY ONE TODAY AT BOOTH #515 #WEAREVQPOWELL POWELLFLUTES.COM Wiseman Flute Cases Compact. Strong. Comfortable. Stylish. And Guaranteed for life. All Wiseman cases are hand- crafted in England from the Visit us at finest materials. booth 408 in All instrument combinations the exhibit hall, supplied – choose from a range of lining colours. Now also NFA 2018 available in Carbon Fibre. Orlando! 00 44 (0)20 8778 0752 [email protected] www.wisemanlondon.com MAKE YOUR MUSIC MATTER Longy has created one of the most outstanding flute departments in the country! Seize the opportunity to study with our world-class faculty including: Cobus du Toit, Antero Winds Clint Foreman, Boston Symphony Orchestra Vanessa Breault Mulvey, Body Mapping Expert Sergio Pallottelli, Flute Faculty at the Zodiac Music Festival Continue your journey towards a meaningful life in music at Longy.edu/apply TABLE OF CONTENTS Letter from the President ................................................................... 11 Officers, Directors, Staff, Convention Volunteers, and Competition Committees ................................................................ 14 From the Convention Program Chair ................................................. 21 2018 Lifetime Achievement and Distinguished Service Awards ........ 22 Previous Lifetime Achievement and Distinguished -

Season 2017-2018

23 Season 2017-2018 Wednesday, November 1, at 7:30 China’s National Centre for the Performing Arts Orchestra Lü Jia Conductor Ning Feng Violin Gautier Capuçon Cello Zhao Jiping Violin Concerto No. 1 (in one movement) Chen Qigang Reflection of a Vanished Time, for cello and orchestra United States premiere Intermission Brahms Symphony No. 4 in E minor, Op. 98 I. Allegro non troppo II. Andante moderato III. Allegro giocoso—Poco meno presto—Tempo I IV. Allegro energico e passionato—Più allegro This program runs approximately 1 hour, 50 minutes. China’s National Centre for the Performing Arts Orchestra’s 2017 US Tour is proudly supported by China National Arts Fund. International Flight Sponsor: Hainan Airlines Philadelphia Orchestra concerts are broadcast on WRTI 90.1 FM on Sunday afternoons at 1 PM. Visit www.wrti.org to listen live or for more details. 24 Conductor Lü Jia is artistic director of music of the National Centre for the Performing Arts (NCPA) in Beijing, China, as well as music director and chief conductor of the NCPA Orchestra. He is also music director and chief conductor of the Macao Orchestra. He has served as music director of Verona Opera in Italy and artistic director of the Tenerife Symphony in Spain. Born into a musical family in Shanghai, he began studying piano and cello at a very young age. He later studied conducting at the Central Conservatory of Music in Beijing, under the tutelage of Zheng Xiaoying. At the age of 24 Mr. Lü entered the University of Arts in Berlin, where he continued his studies under Hans- Martin Rabenstein and Robert Wolf. -

Resource Guide for Educators and Students Grades 4–12

Resource Guide for Educators and Students Grades 4–12 What is traditional music? It’s music that's passed on from one person to another, music that arises from one or more cultures, from their history and geography. It's music that can tell a story or evoke emotions ranging from celebratory joy to quiet reflection. Traditional music is usually played live in community settings such as dances, people's houses and small halls. In each 30-minute episode of Carry On™, musical explorer and TikTok sensation Hal Walker interviews a musician who plays traditional music. Episodes air live, allowing students to pose questions. Programs are then archived so you can listen to them any time from your classroom or home. Visit Carry On's YouTube channel for live shows and archived episodes. Episode 7, Tina Bergmann Tina Bergmann is a fourth-generation musician from northeast Ohio who began performing at age 8 and teaching at age 12. She learned the mountain dulcimer from her mother in the aural tradition (by ear) and the hammered dulcimer from builder, performer and West Virginia native Loy Swiger. She makes her living teaching and performing. She performs on her own, with her husband bassist Bryan Thomas and with two groups, Apollo's Fire and Hu$hmoney string band. Even though the hammered dulcimer has strings, it's considered a percussion instrument because the strings are struck (like the piano). Percussion instruments like the hammered dulcimer can play melody and harmony. But because the sound fades quickly after the string is struck, it has to be struck again and again—and so rhythm becomes an important musical element with this (and any) percussion instrument.