Imagining the Japanese Masses In

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Micro-Broadcasting: License-Free Campus Radio in This Issue: • Carey Junior High School ARC • WEFAX Reception on an Ipad • MT Reviews: MFJ Mini-Frequency Counter

www.monitoringtimes.com Scanning - Shortwave - Ham Radio - Equipment Internet Streaming - Computers - Antique Radio ® Volume 30, No. 9 September 2011 U.S. $6.95 Can. $6.95 Printed in the United States A Publication of Grove Enterprises Micro-Broadcasting: License-Free Campus Radio In this issue: • Carey Junior High School ARC • WEFAX Reception on an iPad • MT Reviews: MFJ Mini-Frequency Counter CONTENTS Vol. 30 No. 9 September 2011 CQ DX from KC7OEK .................................................... 12 www.monitoringtimes.com By Nick Casner K7CAS, Cole Smith KF7FXW and Rayann Brown KF7KEZ Scanning - Shortwave - Ham Radio - Equipment Internet Streaming - Computers - Antique Radio Eighteen years ago Paul Crips KI7TS and Bob Mathews K7FDL wrote a grant ® Volume 30, No. 9 September 2011 U.S. $6.95 through the Wyoming Department of Education that resulted in the establishment Can. $6.95 Printed in the United States A Publication of Grove Enterprises of an amateur radio club station at Carey Junior High School in Cheyenne, Wyoming, known on the air as KC7OEK. Since then some 5,000 students have been introduced to amateur radio; nearly 40 students have been licensed, and last year there were 24 students in the club, seven of whom were ready to test for their own amateur radio licenses. In this article, Carey Junior High School students Nick, Cole and Rayann, all three of whom have received their licenses, relate their experiences with amateur radio both on and off the air. While older hams many times their ages are discouraged Micro-Broadcasting: about the direction of the hobby, these students let us all know that the future of License-Free Campus Radio amateur radio is already in good hands. -

Joseonhakgyo, Learning Under North Korean Leadership: Transitioning from 1970 to Present*

https://doi.org/10.33728/ijkus.2020.29.1.007 International Journal of Korean Unification Studies Vol. 29, No. 1, 2020, 161-188. Joseonhakgyo, Learning under North Korean Leadership: Transitioning from 1970 to Present* Min Hye Cho** This paper analyzes English as a Foreign Language (EFL) textbooks used during North Korea’s three leaderships: 1970s, 1990s and present. The textbooks have been used at Korean ethnic schools, Joseonhakgyo (朝鮮学校), which are managed by the Chongryon (總聯) organization in Japan. The organization is affiliated with North Korea despite its South Korean origins. Given North Korea’s changing influence over Chongryon’s education system, this study investigates how Chongryon Koreans’ view on themselves has undergone a transition. The textbooks’ content that have been used in junior high school classrooms (students aged between thirteen and fifteen years) are analyzed. Selected texts from these textbooks are analyzed critically to delineate the changing views of Chongryon Koreans. The findings demonstrate that Chongryon Koreans have changed their perspective from focusing on their ties to North Korea (1970s) to focusing on surviving as a minority group (1990s) to finally recognising that they reside permanently in Japan (present). Keywords: EFL textbooks, Korean ethnic school, minority education, North Koreans in Japan, North Korean leadership ** Acknowledgments: The author would like to acknowledge the generous and thoughtful support of the staff at Hagusobang (Chongryon publishing company), including Mr Nam In Ryang, Ms Kyong Suk Kim and Ms Mi Ja Moon; Ms Malryo Jang, an English teacher at Joseonhakgyo; and Mr Seong Bok Kang at Joseon University in Tokyo. They have consistently provided primary resource materials, such as Chongryon EFL textbooks, which made this research project possible. -

Pdf/Rosen Eng.Pdf Rice fields) Connnecting Otsuki to Mt.Fuji and Kawaguchiko

Iizaka Onsen Yonesaka Line Yonesaka Yamagata Shinkansen TOKYO & AROUND TOKYO Ōu Line Iizakaonsen Local area sightseeing recommendations 1 Awashima Port Sado Gold Mine Iyoboya Salmon Fukushima Ryotsu Port Museum Transportation Welcome to Fukushima Niigata Tochigi Akadomari Port Abukuma Express ❶ ❷ ❸ Murakami Takayu Onsen JAPAN Tarai-bune (tub boat) Experience Fukushima Ogi Port Iwafune Port Mt.Azumakofuji Hanamiyama Sakamachi Tuchiyu Onsen Fukushima City Fruit picking Gran Deco Snow Resort Bandai-Azuma TTOOKKYYOO information Niigata Port Skyline Itoigawa UNESCO Global Geopark Oiran Dochu Courtesan Procession Urabandai Teradomari Port Goshiki-numa Ponds Dake Onsen Marine Dream Nou Yahiko Niigata & Kitakata ramen Kasumigajo & Furumachi Geigi Airport Urabandai Highland Ibaraki Gunma ❹ ❺ Airport Limousine Bus Kitakata Park Naoetsu Port Echigo Line Hakushin Line Bandai Bunsui Yoshida Shibata Aizu-Wakamatsu Inawashiro Yahiko Line Niigata Atami Ban-etsu- Onsen Nishi-Wakamatsu West Line Nagaoka Railway Aizu Nō Naoetsu Saigata Kashiwazaki Tsukioka Lake Itoigawa Sanjo Firework Show Uetsu Line Onsen Inawashiro AARROOUUNNDD Shoun Sanso Garden Tsubamesanjō Blacksmith Niitsu Takada Takada Park Nishikigoi no sato Jōetsu Higashiyama Kamou Terraced Rice Paddies Shinkansen Dojo Ashinomaki-Onsen Takashiba Ouchi-juku Onsen Tōhoku Line Myoko Kogen Hokuhoku Line Shin-etsu Line Nagaoka Higashi- Sanjō Ban-etsu-West Line Deko Residence Tsuruga-jo Jōetsumyōkō Onsen Village Shin-etsu Yunokami-Onsen Railway Echigo TOKImeki Line Hokkaid T Kōriyama Funehiki Hokuriku -

February 2020 Ajet

AJET News & Events, Arts & Culture, Lifestyle, Community FEBRUARY 2020 Riding the Jiu-Jitsu Wave Working for the Kyoryokutai The Changing Colors of the Red and White Singing Battle Journey Through Magic Embarrassing Adventures of an Expat in Tokyo The Japanese Lifestyle & Culture Magazine Written by the International Community in Japan1 In response to ongoing global news, the team at Connect Magazine would like to acknowledge the devastating impact of the 2019-2020 bushfires in Australia. Our thoughts and support are with those suffering. 2 Since September 2019, the raging fires across the eastern and southeastern Australian coastal regions have burned over 17.9 million acres, destroyed over 2000 homes, and killed least 27 people. A billion animals have been caught in the fires, with some species now pushed to the brink of extinction. Skies are reddened from air heavy with smoke— smoke which can be seen 2,000km away in New Zealand and even from Chile, South America, which is more than 11,000km away. Currently, massive efforts are being taken to tackle the bushfires and protect people, animals, and homes in the vicinity. If you would like to be a part of this effort, here are some resources you can use to help: Country Fire Authority Country Fire Service Foundation In Victoria In South Australia New South Wales Rural The Australian Red Cross Fire Service Fire recovery and relief fund World Wildlife Fund GIVIT Caring for injured wildlife and Donating items requested by habitat restoration those affected The Animal Rescue Collective Craft Guild Making bedding and bandaging for injured animals. -

Other Top Reasons to Visit Hakone

MAY 2016 Japan’s number one English language magazine Other Top Reasons to Visit Hakone ALSO: M83 Interview, Sake Beauty Secrets, Faces of Tokyo’s LGBT Community, Hiromi Miyake Lifts for Gold, Best New Restaurants 2 | MAY 2016 | TOKYO WEEKENDER 7 17 29 32 MAY 2016 guide radar 26 THE FLOWER GUY CULTURE ROUNDUP THIS MONTH’S HEAD TURNERS Nicolai Bergmann on his upcoming shows and the impact of his famed flower boxes 7 AREA GUIDE: EBISU 41 THE ART WORLD Must-see exhibitions including Ryan McGin- Already know the neighborhood? We’ve 28 JUNK ROCK ley’s nudes and Ville Andersson’s “silent” art thrown in a few new spots to explore We chat to M83 frontman Anthony Gon- zalez ahead of his Tokyo performance this 10 STYLE WISH LIST 43 MOVIES month Three films from Japanese distributor Gaga Spring fashion for in-between weather, star- that you don’t want to miss ring Miu Miu pumps and Gucci loafers 29 BEING LGBT IN JAPAN To celebrate Tokyo Rainbow Pride, we 12 TRENDS 44 AGENDA invited popular personalities to share their Escape with electro, join Tokyo’s wildest mat- Good news for global foodies: prepare to experiences suri, and be inspired at Design Festa Vol. 43 enjoy Greek, German, and British cuisine 32 BEAUTY 46 PEOPLE, PARTIES, PLACES The secrets of sake for beautiful skin, and Dewi and her dogs hit Yoyogi and Leo in-depth Andaz Tokyo’s brand-new spa menu COFFEE-BREAK READS DiCaprio comes to town 17 HAKONE TRAVEL SPECIAL 34 GIRL POWER 50 BACK IN THE DAY Our nine-page guide offers tips on what to Could Hiromi Miyake be Japan’s next This month in 1981: “Young Texan Becomes do, where to stay, and how to get around gold-winning weightlifter? Sumodom’s 1st Caucasian Tryout” TOKYO WEEKENDER | MAY 2016 | 3 THIS MONTH IN THE WEEKENDER Easier navigation Keep an eye out for MAY 2016 a new set of sections that let you, the MAY 2016 reader, have a clear set of what’s going where. -

American Forces Network Radio Programming Decisions (D-2006-117)

September 27, 2006 Information Technology Management American Forces Network Radio Programming Decisions (D-2006-117) Department of Defense Office of Inspector General Quality Integrity Accountability Additional Copies To obtain additional copies of this report, visit the Web site of the Department of Defense Inspector General at http://www.dodig.mil/audit/reports or contact the Secondary Reports Distribution Unit at (703) 604-8937 (DSN 664-8937) or fax (703) 604-8932. Suggestions for Future Audits To suggest ideas for or to request future audits, contact the Office of the Deputy Inspector General for Auditing at (703) 604-8940 (DSN 664-8940) or fax (703) 604-8932. Ideas and requests can also be mailed to: ODIG-AUD (ATTN: Audit Suggestions) Department of Defense Inspector General 400 Army Navy Drive (Room 801) Arlington, VA 22202-4704 Acronyms AFIS American Forces Information Service AFN American Forces Network AFRTS American Forces Radio and Television Service AFN-BC American Forces Network - Broadcast Center ASD(PA) Assistant Secretary of Defense (Public Affairs) OIG Office of Inspector General Department of Defense Office of Inspector General Report No. D-2006-117 September 27, 2006 (Project No. D2006-D000FI-0103.000) American Forces Network Radio Programming Decisions Executive Summary Who Should Read This Report and Why? This report will be of interest to DoD personnel responsible for the selection and distribution of talk-radio programming to overseas U.S. Forces and their family members and military personnel serving onboard ships. The report discusses the controls and processes needed for establishing a diverse inventory of talk-radio programming on American Forces Network Radio. -

Grand Opening of Q Plaza IKEBUKURO July 19 (Fri), 10.30 Am Ikebukuro’S Newest Landmark

July 17, 2019 Tokyu Land Corporation Tokyu Land SC Management Corporation Grand Opening of Q Plaza IKEBUKURO July 19 (Fri), 10.30 am Ikebukuro’s Newest Landmark Tokyu Land Corporation (Head office: Minato-ku, Tokyo; President: Yuji Okuma; hereafter “Tokyu Land”) and Tokyu Land SC Management Corporation (Head office: Minato-ku, Tokyo; President: Toshihiro Awatsuji) will open Q Plaza IKEBUKURO at 10.30 am on July 19 (Fri) as Ikeburo’s newest landmark, based on Toshima Ward’s International City of Arts & Culture Toshima vision. As a new entertainment complex where people of all ages can have fun, enjoying different experiences all day long on its 16 stores, including a cinema complex, an arcade and amusement center, and retail and dining options, Q Plaza IKEBUKUO will create more bustle in the Ikebukuro area, which is currently being redeveloped, and will bring life to the district in partnership with the local community. ■Many products exclusive to Q Plaza IKEBUKURO and limited time services to commemorate opening Opening for the first time in the area as flagship store, the AWESOME STORE & CAFÉ will offer a lineup of products exclusive to the Ikebukuro store, including AWESOME FLY! PO!!! with three flavors to choose from and a tuna egg bacon omelette bagel. In commemoration of the opening, Schmatz Beer Dining will offer sausages developed by Takeshi Murakami, a sausage researcher with a workshop in Yamanashi, for a limited time only. It will also provide customers with one free beer and a 19% discount for table-only reservations to commemorate the opening of its 19th store. -

Ancient Magic and Modern Accessories: Developments in the Omamori Phenomenon

Western Michigan University ScholarWorks at WMU Master's Theses Graduate College 8-2015 Ancient Magic and Modern Accessories: Developments in the Omamori Phenomenon Eric Teixeira Mendes Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wmich.edu/masters_theses Part of the Asian History Commons, Buddhist Studies Commons, and the History of Religions of Eastern Origins Commons Recommended Citation Mendes, Eric Teixeira, "Ancient Magic and Modern Accessories: Developments in the Omamori Phenomenon" (2015). Master's Theses. 626. https://scholarworks.wmich.edu/masters_theses/626 This Masters Thesis-Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate College at ScholarWorks at WMU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Master's Theses by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at WMU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ANCIENT MAGIC AND MODERN ACCESSORIES: DEVELOPMENTS IN THE OMAMORI PHENOMENON by Eric Teixeira Mendes A thesis submitted to the Graduate College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Comparative Religion Western Michigan University August 2015 Thesis Committee: Stephen Covell, Ph.D., Chair LouAnn Wurst, Ph.D. Brian C. Wilson, Ph.D. ANCIENT MAGIC AND MODERN ACCESSORIES: DEVELOPMENTS IN THE OMAMORI PHENOMENON Eric Teixeira Mendes, M.A. Western Michigan University, 2015 This thesis offers an examination of modern Japanese amulets, called omamori, distributed by Buddhist temples and Shinto shrines throughout Japan. As amulets, these objects are meant to be carried by a person at all times in which they wish to receive the benefits that an omamori is said to offer. In modern times, in addition to being a religious object, these amulets have become accessories for cell-phones, bags, purses, and automobiles. -

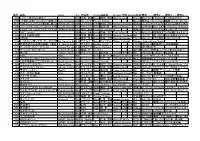

番号 曲名 Name インデックス 作曲者 Composer 編曲者 Arranger作詞

番号 曲名 Name インデックス作曲者 Composer編曲者 Arranger作詞 Words出版社 備考 備考2 備考3 備考4 595 1 2 3 ~恋がはじまる~ 123Koigahajimaru水野 良樹 Yoshiki鄕間 幹男 Mizuno Mikio Gouma ウィンズスコアWSJ-13-020「カルピスウォーター」CMソングいきものがかり 1030 17世紀の古いハンガリー舞曲(クラリネット4重奏)Early Hungarian 17thDances フェレンク・ファルカシュcentury from EarlytheFerenc 17th Hungarian century Farkas Dances from the Musica 取次店:HalBudapest/ミュージカ・ブダペスト Leonard/ハル・レナード編成:E♭Cl./B♭Cl.×2/B.Cl HL50510565 1181 24のプレリュードより第4番、第17番24Preludes Op.28-4,1724Preludesフレデリック・フランソワ・ショパン Op.28-4,17Frédéric福田 洋介 François YousukeChopin Fukuda 音楽之友社バンドジャーナル2019年2月スコアは4番と17番分けてあります 840 スリー・ラテン・ダンス(サックス4重奏)3 Latin Dances 3 Latinパトリック・ヒケティック Dances Patric 尾形Hiketick 誠 Makoto Ogata ブレーンECW-0010Sax SATB1.Charanga di Xiomara Reyes 2.Merengue Sempre di Aychem sunal 3.Dansa Lationo di Maria del Real 997 3☆3ダンス ソロトライアングルと吹奏楽のための 3☆3Dance福島 弘和 Hirokazu Fukushima 音楽之友社バンドジャーナル2017年6月号サンサンダンス(日本語) スリースリーダンス(英語) トレトレダンス(イタリア語) トゥワトゥワダンス(フランス語) 973 360°(miwa) 360domiwa、NAOKI-Tmiwa、NAOKI-T西條 太貴 Taiki Saijyo ウィンズスコアWSJ-15-012劇場版アニメ「映画ドラえもん のび太の宇宙英雄記(スペースヒーローズ)」主題歌 856 365日の紙飛行機 365NichinoKamihikouki角野 寿和 / 青葉 紘季Toshikazu本澤なおゆき Kadono / HirokiNaoyuki Honzawa Aoba M8 QH1557 歌:AKB48 NHK連続テレビ小説『あさが来た』主題歌 685 3月9日 3Gatu9ka藤巻 亮太 Ryouta原田 大雪 Fujimaki Hiroyuki Harada ウィンズスコアWSL-07-0052005年秋に放送されたフジテレビ系ドラマ「1リットルの涙」の挿入歌レミオロメン歌 1164 6つのカノン風ソナタ オーボエ2重奏Six Canonic Sonatas6 Canonicゲオルク・フィリップ・テレマン SonatasGeorg ウィリアム・シュミットPhilipp TELEMANNWilliam Schmidt Western International Music 470 吹奏楽のための第2組曲 1楽章 行進曲Ⅰ.March from Ⅰ.March2nd Suiteグスタフ・ホルスト infrom F for 2ndGustav Military Suite Holst -

Senkawa, Takamatsu, Chihaya, Kanamecho Ikebukuro Station's

Sunshine City is one of the largest multi-facility urban complex Ikebukuro Station is said to be one of the biggest railway terminals in Tokyo, Japan. in Japan. It consists of 5 buildings, including Sunshine It contains the JR Yamanote Line, the JR Saikyo Line, the Tobu Tojo Line, the Seibu Ikebukuro Ikebukuro Station’s 60, a landmark of Ikebukuro, at its center. It is made up of Line, Tokyo Metro Marunouchi Line, Yurakucho Line, Fukutoshin Line, etc., Sunshine City shops and restaurants, an aquarium, a planetarium, indoor Narita Express directly connects Ikebukuro Station and Narita International Airport. West Exit theme parks etc., A variety of fairs and events are held at It is a very convenient place for shopping and people can get whichever they might require Funsui-hiroba (the Fountain Plaza) in ALPA. because the station buildings and department stores are directly connected, such as Tobu Department Store, LUMINE, TOBU HOPE CENTER, Echika, Esola, etc., Jiyu Gakuen Myōnichi-kan Funsui-hiroba (the Fountain Plaza) In addition, various cultural events are held at Tokyo Metropolitan eater and Ikebukuro Nishiguchi Park on the west side of Ikebukuro Station. A ten-minute-walk from the West Exit will bring you to historic buildings such as Jiyu Gakuen Myōnichi-kan, a pioneering school of liberal education for Japan’s women and designed by Frank Lloyd Wright, Rikkyo University, the oldest Christianity University, and the Former Residence of Rampo Edogawa, a leading author of Japanese detective stories. J-WORLD TOKYO Sunshine City Rikkyo University and “Suzukake-no- michi” ©尾 田 栄 一 郎 / 集 英 社・フ ジ テ レ ビ・東 映 ア ニ メ ー シ ョ ン Pokémon Center MEGA TOKYO Tokyo Yosakoi Former Residence of Rampo Edogawa Konica Minolta Planetarium “Manten” Sunshine Aquarium Senkawa, Takamatsu, NAMJATOWN Chihaya, Kanamecho Tokyo Metropolitan Theater Ikebukuro Station’s Until about 1950, there were many ateliers around this area, and young painters and East Exit sculptors worked hard. -

TOC East Asian Journal of Popular Culture, Vol 5, Issue 2 (2019)

H-Japan TOC East Asian Journal of Popular Culture, Vol 5, Issue 2 (2019) Discussion published by Janet Goodwin on Saturday, November 9, 2019 Crosspost from H-Asia Discussion published by Tessa Mathieson on Friday, November 8, 2019 Intellect is pleased to announce that East Asian Journal of Popular Culture 5.2 is now available! Special Issue: ‘Reconsidering the cultural significance of NHK’s morning dramas’ For more information about the special issue and journal, click here >> https://www.ingentaconnect.com/content/intellect/eapc/2019/00000005/00000002?fbclid=IwAR3 N0yNirJb8psFDkcJxlHjiyk_OEh_DFYSTfGpSOdwVQ9Dm8hG-jdBQgMA Issue 5.2 Editorial from Editors-in-chief East Asian Journal of Popular Culture Kate Taylor-Jones, Edward Vickers and Ann Heylen Editorial Revisiting a national institution: NHK’s morning drama (asadora) in transition Elisabeth Scherer Thematic Articles Citation: Janet Goodwin. TOC East Asian Journal of Popular Culture, Vol 5, Issue 2 (2019). H-Japan. 11-09-2019. https://networks.h-net.org/node/20904/discussions/5320001/toc-east-asian-journal-popular-culture-vol-5-issue-2-2019 Licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 3.0 United States License. 1 H-Japan An everyday glimpse of the nation: NHK’s morning drama (asadora) and rituality Elisabeth Scherer The war’s end: 15 August 1945 in NHK’s morning dramas from 1966 to 2019 Sachiko Masuda Television and the ama: The continuing search for a real Japan in NHK’s morning drama Amachan Dolores P. Martinez Tourism and local identity generated by NHK’s morning drama: The intersection of memory and imagination in Kobe Kyungjae Jang The Japanization of wife and whisky in NHK’s morning drama Massan Tim oThelen Interview In-between with Kimberley Pace Scott Sommers Field Report Japan Now North festival report Citation: Janet Goodwin. -

An Analysis of Twentieth-Century Flute Sonatas by Ikuma Dan, Hikaru

Flute Repertoire from Japan: An Analysis of Twentieth-Century Flute Sonatas by Ikuma Dan, Hikaru Hayashi, and Akira Tamba D.M.A. Document Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Musical Arts in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Daniel Ryan Gallagher, M.M. Graduate Program in Music The Ohio State University 2019 D.M.A. Document Committee: Professor Katherine Borst Jones, Advisor Dr. Arved Ashby Dr. Caroline Hartig Professor Karen Pierson 1 Copyrighted by Daniel Ryan Gallagher 2019 2 Abstract Despite the significant number of compositions by influential Japanese composers, Japanese flute repertoire remains largely unknown outside of Japan. Apart from standard unaccompanied works by Tōru Takemitsu and Kazuo Fukushima, other Japanese flute compositions have yet to establish a permanent place in the standard flute repertoire. The purpose of this document is to broaden awareness of Japanese flute compositions through the discussion, analysis, and evaluation of substantial flute sonatas by three important Japanese composers: Ikuma Dan (1924-2001), Hikaru Hayashi (1931- 2012), and Akira Tamba (b. 1932). A brief history of traditional Japanese flute music, a summary of Western influences in Japan’s musical development, and an overview of major Japanese flute compositions are included to provide historical and musical context for the composers and works in this document. Discussions on each composer’s background, flute works, and compositional style inform the following flute sonata analyses, which reveal the unique musical language and characteristics that qualify each work for inclusion in the standard flute repertoire. These analyses intend to increase awareness and performance of other Japanese flute compositions specifically and lesser- known repertoire generally.