Linguistics: Overview Concern for Precise Definition, Clear and Comprehen• Sive Description, and More Powerful Explanation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Empirical Base of Linguistics: Grammaticality Judgments and Linguistic Methodology

UCLA UCLA Previously Published Works Title The empirical base of linguistics: Grammaticality judgments and linguistic methodology Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/05b2s4wg ISBN 978-3946234043 Author Schütze, Carson T Publication Date 2016-02-01 DOI 10.17169/langsci.b89.101 Data Availability The data associated with this publication are managed by: Language Science Press, Berlin Peer reviewed eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California The empirical base of linguistics Grammaticality judgments and linguistic methodology Carson T. Schütze language Classics in Linguistics 2 science press Classics in Linguistics Chief Editors: Martin Haspelmath, Stefan Müller In this series: 1. Lehmann, Christian. Thoughts on grammaticalization 2. Schütze, Carson T. The empirical base of linguistics: Grammaticality judgments and linguistic methodology 3. Bickerton, Derek. Roots of language ISSN: 2366-374X The empirical base of linguistics Grammaticality judgments and linguistic methodology Carson T. Schütze language science press Carson T. Schütze. 2019. The empirical base of linguistics: Grammaticality judgments and linguistic methodology (Classics in Linguistics 2). Berlin: Language Science Press. This title can be downloaded at: http://langsci-press.org/catalog/book/89 © 2019, Carson T. Schütze Published under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 Licence (CC BY 4.0): http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ ISBN: 978-3-946234-02-9 (Digital) 978-3-946234-03-6 (Hardcover) 978-3-946234-04-3 (Softcover) 978-1-523743-32-2 -

CAS LX 522 Syntax I

It is likely… CAS LX 522 IP This satisfies the EPP in Syntax I both clauses. The main DPj I′ clause has Mary in SpecIP. Mary The embedded clause has Vi+I VP is the trace in SpecIP. V AP Week 14b. PRO and control ti This specific instance of A- A IP movement, where we move a likely subject from an embedded DP I′ clause to a higher clause is tj generally called subject raising. I VP to leave Reluctance to leave Reluctance to leave Now, consider: Reluctant has two θ-roles to assign. Mary is reluctant to leave. One to the one feeling the reluctance (Experiencer) One to the proposition about which the reluctance holds (Proposition) This looks very similar to Mary is likely to leave. Can we draw the same kind of tree for it? Leave has one θ-role to assign. To the one doing the leaving (Agent). How many θ-roles does reluctant assign? In Mary is reluctant to leave, what θ-role does Mary get? IP Reluctance to leave Reluctance… DPi I′ Mary Vj+I VP In Mary is reluctant to leave, is V AP Mary is doing the leaving, gets Agent t Mary is reluctant to leave. j t from leave. i A′ Reluctant assigns its θ- Mary is showing the reluctance, gets θ roles within AP as A θ IP Experiencer from reluctant. required, Mary moves reluctant up to SpecIP in the main I′ clause by Spellout. ? And we have a problem: I vP But what gets the θ-role to Mary appears to be getting two θ-roles, from leave, and what v′ in violation of the θ-criterion. -

Greek and Latin Roots, Prefixes, and Suffixes

GREEK AND LATIN ROOTS, PREFIXES, AND SUFFIXES This is a resource pack that I put together for myself to teach roots, prefixes, and suffixes as part of a separate vocabulary class (short weekly sessions). It is a combination of helpful resources that I have found on the web as well as some tips of my own (such as the simple lesson plan). Lesson Plan Ideas ........................................................................................................... 3 Simple Lesson Plan for Word Study: ........................................................................... 3 Lesson Plan Idea 2 ...................................................................................................... 3 Background Information .................................................................................................. 5 Why Study Word Roots, Prefixes, and Suffixes? ......................................................... 6 Latin and Greek Word Elements .............................................................................. 6 Latin Roots, Prefixes, and Suffixes .......................................................................... 6 Root, Prefix, and Suffix Lists ........................................................................................... 8 List 1: MEGA root list ................................................................................................... 9 List 2: Roots, Prefixes, and Suffixes .......................................................................... 32 List 3: Prefix List ...................................................................................................... -

Language Structure: Phrases “Productivity” a Property of Language • Definition – Language Is an Open System

Language Structure: Phrases “Productivity” a property of Language • Definition – Language is an open system. We can produce potentially an infinite number of different messages by combining elements differently. • Example – Words into phrases. An Example of Productivity • Human language is a communication system that bears some similarities to other animal communication systems, but is also characterized by certain unique features. (24 words) • I think that human language is a communication system that bears some similarities to other animal communication systems, but is also characterized by certain unique features, which are fascinating in and of themselves. (33 words) • I have always thought, and I have spent many years verifying, that human language is a communication system that bears some similarities to other animal communication systems, but is also characterized by certain unique features, which are fascinating in and of themselves. (42 words) • Although mainstream some people might not agree with me, I have always thought… Creating Infinite Messages • Discrete elements – Words, Phrases • Selection – Ease, Meaning, Identity • Combination – Rules of organization Models of Word reCombination 1. Word chains (Markov model) Phrase-level meaning is derived from understanding each word as it is presented in the context of immediately adjacent words. 2. Hierarchical model There are long-distant dependencies between words in a phrase, and these inform the meaning of the entire phrase. Markov Model Rule: Select and concatenate (according to meaning and what types of words should occur next to each other). bites bites bites Man over over over jumps jumps jumps house house house Markov Model • Assumption −Only adjacent words are meaningfully (and lawfully) related. -

24.902F15 Class 13 Pro Versus

Unpronounced subjects 1 We have seen PRO, the subject of infinitives and gerunds: 1. I want [PRO to dance in the park] 2. [PRO dancing in the park] was a good idea 2 There are languages that have unpronounced subjects in tensed clauses. Obviously, English is not among those languages: 3. irθe (Greek) came.3sg ‘he came’ or ‘she came’ 4. *came Languages like Greek, which permit this phenomenon are called “pro-drop” languages. 3 What is the status of this unpronounced subject in pro-drop languages? Is it PRO or something else? Something with the same or different properties from PRO? Let’s follow the convention of calling the unpronounced subject in tensed clauses “little pro”, as opposed to “big PRO”. What are the differences between pro and PRO? 4 -A Nominative NP can appear instead of pro. Not so for PRO: 5. i Katerina irθe the Katerina came.3sg ‘Katerina came’ 6. *I hope he/I to come 7. *he to read this book would be great 5 -pro can refer to any individual as long as Binding Condition B is respected. That is, pro is not “controlled”. Not so for OC PRO. 8. i Katerinak nomizi oti prok/m irθe stin ora tis the K thinks that came on-the time her ‘Katerinak thinks that shek/m /hem came on time’ 9. Katerinak wants [PROk/*m to leave] 6 -pro can yield sloppy or strict readings under ellipsis, exactly like pronouns. Not so OC PRO. 10. i Katerinak nomizi oti prok/m irθe stin ora tis the K thinks that came on-the time her ke i Maria episis and the Maria also ‘Katerinak thinks that shek came on time and Maria does too’ =…Maria thinks that Katerina came on time strict …Maria thinks that Maria came on time sloppy 7 11. -

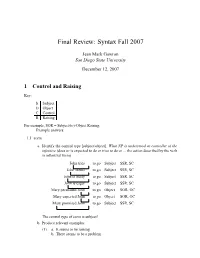

Final Review: Syntax Fall 2007

Final Review: Syntax Fall 2007 Jean Mark Gawron San Diego State University December 12, 2007 1 Control and Raising Key: S Subject O Object C Control R Raising For example, SOR = Subject(to)-Object Raising. Example answers: 1.1 seem a. Identify the control type [subject/object]. What NP is understood as controller of the infinitive (does or is expected to do or tries to do or ... the action described by the verb in infinitival form) John tries to go Subject SSR, SC John seems to go Subject SSR, SC John is likely to go Subject SSR, SC John is eager to go Subject SSR, SC Mary persuaded John to go Object SOR, OC Mary expected John to go Object SOR, OC Mary promised John to go Subject SSR, SC The control type of seem is subject! b. Produce relevant examples: (1) a. Itseemstoberaining b. There seems to be a problem c. The chips seems to be down. d. It seems to be obvious that John is a fool. e. The police seem to have caught the burglar. f. The burglar seems to have been caught by the police. c. Example construction i. Construct embedded clause: (a) itrains. Simpleexample;dummysubject * John rains Testing dummy subjecthood ittorain Putintoinfinitivalform ii. Embed (a) ∆ seem [CP it to rain] Embed under seem [ctd.] it seem [CP t torain] Moveit— it seems [CP t to rain] Add tense, agreement (to main verb) d. Other examples (b) itisraining. Alternativeexample;dummysubject *Johnisraining Testingdummysubjecthood ittoberaining Putintoinfinitivalform ∆ seem [CP it to be raining] Embed under seem it seem [CP t toberaining] Moveit— it seems [CP t to be raining] Add tense, agreement (to main verb) (c) Thechipsaredown. -

Experimenting with Pro-Drop in Spanish1

Andrea Pešková Experimenting with Pro-drop in Spanish1 Abstract This paper investigates the omission and expression of pronominal subjects (PS) in Buenos Aires Spanish based on data from a production experiment. The use of PS is a linguistic phenomenon demonstrating that the grammar of a language needs to be considered independently of its usage. Despite the fact that the observed Spanish variety is a consistent pro-drop language with rich verbal agreement, the data from the present study provide evidence for a quite frequent use of overt PS, even in non-focal, non- contrastive and non-ambiguous contexts. This result thus supports previous corpus- based empirical research and contradicts the traditional explanation given by grammarians that overtly realized PS in Spanish are used to avoid possible ambiguities or to mark contrast and emphasis. Moreover, the elicited semi-spontaneous data indicate that the expression of PS is optional; however, this optionality is associated with different linguistic factors. The statistical analysis of the data shows the following ranking of the effects of these factors: grammatical persons > verb semantics > (syntactic) clause type > (semantic) sentence type. 1. Introduction It is well known that Spanish is a pro-drop (“pronoun-dropping”) or null- subject language whose grammar permits the omission of pronominal 1 A preliminary version of this paper was presented at the international conference Variation and typology: New trends in syntactic research in Helsinki (August 2011). I am grateful to the audience for their fruitful discussions and useful commentaries. I would also like to thank the editors, Susann Fischer, Ingo Feldhausen, Christoph Gabriel and the anonymous reviewers for their detailed and helpful comments on an earlier version of this article. -

The Position of Subjects*

Lingua 85 (1991) 21 l-258. North-Holland 211 The position of subjects* Hilda Koopman and Dominique Sportiche Department of Linguistics, UCLA, Los Angeles, CA 90024, USA Grammatical theories all use in one form or another the concept of canonical position of a phrase. If this notion is used in the syntax, when comparing the two sentences: (la) John will see Bill. (1 b) Bill John will see. we say that Bill occupies its canonical position in (la) but not in (lb). Adopting the terminology of the Extended Standard Theory, we can think of the canonical position of a phrase as its D-structure position. Since the concept of canonical position is available, it becomes legitimate to ask of each syntactic unit in a given sentence what its canonical position is, relative to the other units of the sentence. The central question we address in this article is: what is the canonical position of subjects1 Starting with English, we propose that the structure of an English clause is as in (2): * The first section of this article has circulated as part of Koopman and Sportiche (1988) and is a written version of talks given in various places. It was given in March 1985 at the GLOW conference in Brussels as Koopman and Sportiche (1985), at the June 1985 CLA meeting in Montreal, at MIT and Umass Amherst in the winter of 1986, and presented at UCLA and USC since. The input of these audiences is gratefully acknowledged. The second section is almost completely new. 1 For related ideas on what we call the canonical postion of subjects, see Contreras (1987), Kitagawa (1986) Kuroda (1988), Speas (1986) Zagona (1982). -

Word Recognition in Two Languages and Orthographies: English and Greek

Memory & Cognition 1994, 22 (3), 313-325 Word recognition in two languages and orthographies: English and Greek HELENA-FIVI CHITIRI St. Francis Xavier University, Antigonish, Nova Scotia, Canada and DALE M. WILLOWS Ontario Institute for Studies in Education, Toronto, Ontario, Canada Word recognition processes of monolingual readers of English and of Greek were examined with respect to the orthographic and syntactic characteristics of each language. Because of Greek's direct letter-to-sound correspondence, which is unlike the indirect representation of English, the possibility was raised of a greater influence of the phonological code in Greek word recognition. Because Greek is an inflected language, whereas English is a word order language, it was also possible that syntax might influence word recognition patterns in the two languages differen tially. These cross-linguistic research questions were investigated within the context of a letter cancellation paradigm. The results provide evidence that readers are sensitive to both the ortho graphic and the linguistic idiosyncracies of their language. The results are discussed in terms of the orthographic depth hypothesis and the competition model. In this research, we examined word recognition in En ber (singular, plural), and the case (nominative, genitive, glish and Greek, two languages with different orthogra accusative, vocative) of the noun. Verb endings provide phies and syntactic characteristics. We examined the rela information about person and number as well as about tionship of orthography to the role of the phonological the voice and the tense of a verb. code in word recognition as it is exemplified in the pro Greek words are typically polysyllabic (Mirambel, cessing of syllabic and stress information. -

Pronominal Vs. Anaphoric Pro in Kannada

Pronominal vs. anaphoric pro in Kannada Anuradha Sudharsan∗ The English and Foreign Languages University Hyderabad, Telangana, India Kannada licenses a pronominal pro and an anaphor pro in root and subordinate clauses. In the subordi- nate clauses, pro’s person feature largely determines its pronominal/anaphoric status. Accordingly, there are four types of pro, each with a distinct referential property. The 1st and 2nd person pros allow pronomi- nal and anaphoric interpretations. In their pronominal reference, they refer to the speaker and the listener, respectively. In their anaphoric reference, they refer to the matrix subject and the object, respectively, irre- spective of the latter’s person feature, which results in a feature mismatch between pro and its antecedent. The 3rd person pro allows only pronominal interpretation. Kannada quotative verbs report direct speech. The null subjects in the embedded clauses of reported speech are basically pronominal because they are ‘copies’ of the pronominal subjects in direct speech. Accordingly, the embedded verbal inflection corre- sponds to inflection in direct speech, which results in a feature clash between pro and its antecedent. The fourth type, a null anaphor, occurs in non-argument endu-clauses. It is bound by an NP in the matrix with which it shares its F-features. It is the semantic relation between the non-argument and main clauses that explains the presence of an anaphoric pro here. Keywords: pro, pronominal, feature clash, anaphor, Kannada 1. Introduction In most studies on the pro-drop parameter, pro was characterized as a pronominal empty category based on evidence from European null subject languages. -

24.910 Topics in Linguistic Theory: Propositional Attitudes Spring 2009

MIT OpenCourseWare http://ocw.mit.edu 24.910 Topics in Linguistic Theory: Propositional Attitudes Spring 2009 For information about citing these materials or our Terms of Use, visit: http://ocw.mit.edu/terms. Mar. 31 24.910, Spring 2009 (Stephenson) Raising and Control Ingredients of analysis (as presented in Carnie text): ¾ Theta-roles / Theta Criterion: Requirement that predicates have exactly the right number of semantic arguments in the same clause (at D-structure) ¾ Abstract Case: Requirement that NPs be in (or move to) one of a few specified positions: Specifier of finite T [for nominative case] Complement to V [for accusative case] [Other possibilities are not relevant for control / raising] ¾ EPP (“Extended Projection Principle”): Requirement that sentences have a subject Four cases: ¾ Subject-to-subject raising ¾ Subject-to-object raising ¾ Subject control ¾ Object control 1.1. Subject-to-subject raising (1) John is likely to leave. ¾ theta-grid for (be) likely: proposition j ¾ theta-grid for leave: Agent i ¾ D-structure: (2) [ __spec is likely [John to leave]TP2 ]TP1 Theta-role of is likely is assigned to John to leave is in TP1 Theta-role of leave is assigned to John Æ Theta Criterion is satisfied BUT: John is in the specifier of the non-finite TP2 Æ can’t get case AND: the EPP is not satisfied (the sentence has no subject) 1 Mar. 31 24.910, Spring 2009 (Stephenson) ¾ John moves to Spec TP1 at S-structure: (3) [ Johni is likely [ _ti _ to leave]TP2 ]TP1 John gets nominative case from the finite T in TP1 EPP is satisfied (since John is the subject) 1.2. -

The Minimalist Program 1 1 the Minimalist Program

The Minimalist Program 1 1 The Minimalist Program Introduction It is my opinion that the implications of the Minimalist Program (MP) are more radical than generally supposed. I do not believe that the main thrust of MP is technical; whether to move features or categories for example. MP suggests that UG has a very different look from the standard picture offered by GB-based theories. This book tries to make good on this claim by outlining an approach to grammar based on one version of MP. I stress at the outset the qualifier “version.” Minimalism is not a theory but a program animated by certain kinds of methodological and substantive regulative ideals. These ideals are reflected in more concrete principles which are in turn used in minimalist models to analyze specific empirical phenomena. What follows is but one way of articulating the MP credo. I hope to convince you that this version spawns grammatical accounts that have a theoretically interesting structure and a fair degree of empirical support. The task, however, is doubly difficult. First, it is unclear what the content of these precepts is. Second, there is a non-negligible distance between the content of such precepts and its formal realization in specific grammatical principles and analyses. The immediate task is to approach the first hurdle and report what I take the precepts and principles of MP to be.1 1 Principles-Parameters and Minimalism MP is many things to many researchers. To my mind it grows out of the per- ceived success of the principles and parameters (P&P) approach to grammatical competence.