Language Structure: Phrases “Productivity” a Property of Language • Definition – Language Is an Open System

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Empirical Base of Linguistics: Grammaticality Judgments and Linguistic Methodology

UCLA UCLA Previously Published Works Title The empirical base of linguistics: Grammaticality judgments and linguistic methodology Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/05b2s4wg ISBN 978-3946234043 Author Schütze, Carson T Publication Date 2016-02-01 DOI 10.17169/langsci.b89.101 Data Availability The data associated with this publication are managed by: Language Science Press, Berlin Peer reviewed eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California The empirical base of linguistics Grammaticality judgments and linguistic methodology Carson T. Schütze language Classics in Linguistics 2 science press Classics in Linguistics Chief Editors: Martin Haspelmath, Stefan Müller In this series: 1. Lehmann, Christian. Thoughts on grammaticalization 2. Schütze, Carson T. The empirical base of linguistics: Grammaticality judgments and linguistic methodology 3. Bickerton, Derek. Roots of language ISSN: 2366-374X The empirical base of linguistics Grammaticality judgments and linguistic methodology Carson T. Schütze language science press Carson T. Schütze. 2019. The empirical base of linguistics: Grammaticality judgments and linguistic methodology (Classics in Linguistics 2). Berlin: Language Science Press. This title can be downloaded at: http://langsci-press.org/catalog/book/89 © 2019, Carson T. Schütze Published under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 Licence (CC BY 4.0): http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ ISBN: 978-3-946234-02-9 (Digital) 978-3-946234-03-6 (Hardcover) 978-3-946234-04-3 (Softcover) 978-1-523743-32-2 -

CAS LX 522 Syntax I

It is likely… CAS LX 522 IP This satisfies the EPP in Syntax I both clauses. The main DPj I′ clause has Mary in SpecIP. Mary The embedded clause has Vi+I VP is the trace in SpecIP. V AP Week 14b. PRO and control ti This specific instance of A- A IP movement, where we move a likely subject from an embedded DP I′ clause to a higher clause is tj generally called subject raising. I VP to leave Reluctance to leave Reluctance to leave Now, consider: Reluctant has two θ-roles to assign. Mary is reluctant to leave. One to the one feeling the reluctance (Experiencer) One to the proposition about which the reluctance holds (Proposition) This looks very similar to Mary is likely to leave. Can we draw the same kind of tree for it? Leave has one θ-role to assign. To the one doing the leaving (Agent). How many θ-roles does reluctant assign? In Mary is reluctant to leave, what θ-role does Mary get? IP Reluctance to leave Reluctance… DPi I′ Mary Vj+I VP In Mary is reluctant to leave, is V AP Mary is doing the leaving, gets Agent t Mary is reluctant to leave. j t from leave. i A′ Reluctant assigns its θ- Mary is showing the reluctance, gets θ roles within AP as A θ IP Experiencer from reluctant. required, Mary moves reluctant up to SpecIP in the main I′ clause by Spellout. ? And we have a problem: I vP But what gets the θ-role to Mary appears to be getting two θ-roles, from leave, and what v′ in violation of the θ-criterion. -

Greek and Latin Roots, Prefixes, and Suffixes

GREEK AND LATIN ROOTS, PREFIXES, AND SUFFIXES This is a resource pack that I put together for myself to teach roots, prefixes, and suffixes as part of a separate vocabulary class (short weekly sessions). It is a combination of helpful resources that I have found on the web as well as some tips of my own (such as the simple lesson plan). Lesson Plan Ideas ........................................................................................................... 3 Simple Lesson Plan for Word Study: ........................................................................... 3 Lesson Plan Idea 2 ...................................................................................................... 3 Background Information .................................................................................................. 5 Why Study Word Roots, Prefixes, and Suffixes? ......................................................... 6 Latin and Greek Word Elements .............................................................................. 6 Latin Roots, Prefixes, and Suffixes .......................................................................... 6 Root, Prefix, and Suffix Lists ........................................................................................... 8 List 1: MEGA root list ................................................................................................... 9 List 2: Roots, Prefixes, and Suffixes .......................................................................... 32 List 3: Prefix List ...................................................................................................... -

Chapter 30 HPSG and Lexical Functional Grammar Stephen Wechsler the University of Texas Ash Asudeh University of Rochester & Carleton University

Chapter 30 HPSG and Lexical Functional Grammar Stephen Wechsler The University of Texas Ash Asudeh University of Rochester & Carleton University This chapter compares two closely related grammatical frameworks, Head-Driven Phrase Structure Grammar (HPSG) and Lexical Functional Grammar (LFG). Among the similarities: both frameworks draw a lexicalist distinction between morphology and syntax, both associate certain words with lexical argument structures, both employ semantic theories based on underspecification, and both are fully explicit and computationally implemented. The two frameworks make available many of the same representational resources. Typical differences between the analyses proffered under the two frameworks can often be traced to concomitant differ- ences of emphasis in the design orientations of their founding formulations: while HPSG’s origins emphasized the formal representation of syntactic locality condi- tions, those of LFG emphasized the formal representation of functional equivalence classes across grammatical structures. Our comparison of the two theories includes a point by point syntactic comparison, after which we turn to an exposition ofGlue Semantics, a theory of semantic composition closely associated with LFG. 1 Introduction Head-Driven Phrase Structure Grammar is similar in many respects to its sister framework, Lexical Functional Grammar or LFG (Bresnan et al. 2016; Dalrymple et al. 2019). Both HPSG and LFG are lexicalist frameworks in the sense that they distinguish between the morphological system that creates words and the syn- tax proper that combines those fully inflected words into phrases and sentences. Stephen Wechsler & Ash Asudeh. 2021. HPSG and Lexical Functional Gram- mar. In Stefan Müller, Anne Abeillé, Robert D. Borsley & Jean- Pierre Koenig (eds.), Head-Driven Phrase Structure Grammar: The handbook. -

Lexical-Functional Grammar and Order-Free Semantic Composition

COLING 82, J. Horeck~(eel) North-HoOandPubllshi~ Company O A~deml~ 1982 Lexical-Functional Grammar and Order-Free Semantic Composition Per-Kristian Halvorsen Norwegian Research Council's Computing Center for the Humanities and Center for Cognitive Science, MIT This paper summarizes the extension of the theory of lexical-functional grammar to include a formal, model-theoretic, semantics. The algorithmic specification of the semantic interpretation procedures is order-free which distinguishes the system from other theories providing model-theoretic interpretation for natural language. Attention is focused on the computational advantages of a semantic interpretation system that takes as its input functional structures as opposed to syntactic surface-structures. A pressing problem for computational linguistics is the development of linguistic theories which are supported by strong independent linguistic argumentation, and which can, simultaneously, serve as a basis for efficient implementations in language processing systems. Linguistic theories with these properties make it possible for computational implementations to build directly on the work of linguists both in the area of grammar-writing, and in the area of theory development (cf. universal conditions on anaphoric binding, filler-gap dependencies etc.). Lexical-functional grammar (LFG) is a linguistic theory which has been developed with equal attention being paid to theoretical linguistic and computational processing considerations (Kaplan & Bresnan 1981). The linguistic theory has ample and broad motivation (vide the papers in Bresnan 1982), and it is transparently implementable as a syntactic parsing system (Kaplan & Halvorsen forthcoming). LFG takes grammatical relations to be of primary importance (as opposed to the transformational theory where grammatical functions play a subsidiary role). -

Processing English with a Generalized Phrase Structure Grammar

PROCESSING ENGLISH WITH A GENERALIZED PHRASE STRUCTURE GRAMMAR Jean Mark Gawron, Jonathan King, John Lamping, Egon Loebner, Eo Anne Paulson, Geoffrey K. Pullum, Ivan A. Sag, and Thomas Wasow Computer Research Center Hewlett Packard Company 1501 Page Mill Road Palo Alto, CA 94304 ABSTRACT can be achieved without detailed syntactic analysis. There is, of course, a massive This paper describes a natural language pragmatic component to human linguistic processing system implemented at Hewlett-Packard's interaction. But we hold that pragmatic inference Computer Research Center. The system's main makes use of a logically prior grammatical and components are: a Generalized Phrase Structure semantic analysis. This can be fruitfully modeled Grammar (GPSG); a top-down parser; a logic and exploited even in the complete absence of any transducer that outputs a first-order logical modeling of pragmatic inferencing capability. representation; and a "disambiguator" that uses However, this does not entail an incompatibility sortal information to convert "normal-form" between our work and research on modeling first-order logical expressions into the query discourse organization and conversational language for HIRE, a relational database hosted in interaction directly= Ultimately, a successful the SPHERE system. We argue that theoretical language understanding system wilt require both developments in GPSG syntax and in Montague kinds of research, combining the advantages of semantics have specific advantages to bring to this precise, grammar-driven analysis of utterance domain of computational linguistics. The syntax structure and pragmatic inferencing based on and semantics of the system are totally discourse structures and knowledge of the world. domain-independent, and thus, in principle, We stress, however, that our concerns at this highly portable. -

24.902F15 Class 13 Pro Versus

Unpronounced subjects 1 We have seen PRO, the subject of infinitives and gerunds: 1. I want [PRO to dance in the park] 2. [PRO dancing in the park] was a good idea 2 There are languages that have unpronounced subjects in tensed clauses. Obviously, English is not among those languages: 3. irθe (Greek) came.3sg ‘he came’ or ‘she came’ 4. *came Languages like Greek, which permit this phenomenon are called “pro-drop” languages. 3 What is the status of this unpronounced subject in pro-drop languages? Is it PRO or something else? Something with the same or different properties from PRO? Let’s follow the convention of calling the unpronounced subject in tensed clauses “little pro”, as opposed to “big PRO”. What are the differences between pro and PRO? 4 -A Nominative NP can appear instead of pro. Not so for PRO: 5. i Katerina irθe the Katerina came.3sg ‘Katerina came’ 6. *I hope he/I to come 7. *he to read this book would be great 5 -pro can refer to any individual as long as Binding Condition B is respected. That is, pro is not “controlled”. Not so for OC PRO. 8. i Katerinak nomizi oti prok/m irθe stin ora tis the K thinks that came on-the time her ‘Katerinak thinks that shek/m /hem came on time’ 9. Katerinak wants [PROk/*m to leave] 6 -pro can yield sloppy or strict readings under ellipsis, exactly like pronouns. Not so OC PRO. 10. i Katerinak nomizi oti prok/m irθe stin ora tis the K thinks that came on-the time her ke i Maria episis and the Maria also ‘Katerinak thinks that shek came on time and Maria does too’ =…Maria thinks that Katerina came on time strict …Maria thinks that Maria came on time sloppy 7 11. -

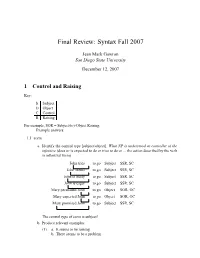

Final Review: Syntax Fall 2007

Final Review: Syntax Fall 2007 Jean Mark Gawron San Diego State University December 12, 2007 1 Control and Raising Key: S Subject O Object C Control R Raising For example, SOR = Subject(to)-Object Raising. Example answers: 1.1 seem a. Identify the control type [subject/object]. What NP is understood as controller of the infinitive (does or is expected to do or tries to do or ... the action described by the verb in infinitival form) John tries to go Subject SSR, SC John seems to go Subject SSR, SC John is likely to go Subject SSR, SC John is eager to go Subject SSR, SC Mary persuaded John to go Object SOR, OC Mary expected John to go Object SOR, OC Mary promised John to go Subject SSR, SC The control type of seem is subject! b. Produce relevant examples: (1) a. Itseemstoberaining b. There seems to be a problem c. The chips seems to be down. d. It seems to be obvious that John is a fool. e. The police seem to have caught the burglar. f. The burglar seems to have been caught by the police. c. Example construction i. Construct embedded clause: (a) itrains. Simpleexample;dummysubject * John rains Testing dummy subjecthood ittorain Putintoinfinitivalform ii. Embed (a) ∆ seem [CP it to rain] Embed under seem [ctd.] it seem [CP t torain] Moveit— it seems [CP t to rain] Add tense, agreement (to main verb) d. Other examples (b) itisraining. Alternativeexample;dummysubject *Johnisraining Testingdummysubjecthood ittoberaining Putintoinfinitivalform ∆ seem [CP it to be raining] Embed under seem it seem [CP t toberaining] Moveit— it seems [CP t to be raining] Add tense, agreement (to main verb) (c) Thechipsaredown. -

Psychoacoustics, Speech Perception, Language Structure and Neurolinguistics Hearing Acuity Absolute Auditory Threshold Constant

David House: Psychoacoustics, speech perception, 2018.01.25 language structure and neurolinguistics Hearing acuity Psychoacoustics, speech perception, language structure • Sensitive for sounds from 20 to 20 000 Hz and neurolinguistics • Greatest sensitivity between 1000-6000 Hz • Non-linear perception of frequency intervals David House – E.g. octaves • 100Hz - 200Hz - 400Hz - 800Hz - 1600Hz – 100Hz - 800Hz perceived as a large difference – 3100Hz - 3800 Hz perceived as a small difference Absolute auditory threshold Demo: SPL (Sound pressure level) dB • Decreasing noise levels – 6 dB steps, 10 steps, 2* – 3 dB steps, 15 steps, 2* – 1 dB steps, 20 steps, 2* Constant loudness levels in phons Demo: SPL and loudness (phons) • 50-100-200-400-800-1600-3200-6400 Hz – 1: constant SPL 40 dB, 2* – 2: constant 40 phons, 2* 1 David House: Psychoacoustics, speech perception, 2018.01.25 language structure and neurolinguistics Critical bands • Bandwidth increases with frequency – 200 Hz (critical bandwidth 50 Hz) – 800 Hz (critical bandwidth 80 Hz) – 3200 Hz (critical bandwidth 200 Hz) Critical bands demo Effects of masking • Fm=200 Hz (critical bandwidth 50 Hz) – B= 300,204,141,99,70,49,35,25,17,12 Hz • Fm=800 Hz (critical bandwidth 80 Hz) – B=816,566,396,279,197,139,98,69,49,35 Hz • Fm=3200 Hz (critical bandwidth 200 Hz) – B=2263,1585,1115,786,555,392,277,196,139,98 Hz Effects of masking Holistic vs. analytic listening • Low frequencies more effectively mask • Demo 1: audible harmonics (1-5) high frequencies • Demo 2: melody with harmonics • Demo: how -

Acquiring Verb Subcategorization from Spanish Corpora

Acquiring Verb Subcategorization from Spanish Corpora Grzegorz ChrupaÃla [email protected] Universitat de Barcelona Department of General Linguistics PhD Program “Cognitive Science and Language” Supervised by Dr. Irene Castell´onMasalles September 2003 Contents 1 Introduction 5 2 Verb Subcategorization in Linguistic Theory 7 2.1 Introduction . 7 2.2 Government-Binding and related approaches . 7 2.3 Categorial Grammar . 9 2.4 Lexical-Functional Grammar . 11 2.5 Generalized Phrase-Structure Grammar . 12 2.6 Head-Driven Phrase-Structure Grammar . 14 2.7 Discussion . 17 3 Diathesis Alternations 19 3.1 Introduction . 19 3.2 Diathesis . 19 3.2.1 Alternations . 20 3.3 Diathesis alternations in Spanish . 21 3.3.1 Change of focus . 22 3.3.2 Underspecification . 26 3.3.3 Resultative construction . 27 3.3.4 Middle construction . 27 3.3.5 Conclusions . 29 4 Verb classification 30 4.1 Introduction . 30 4.2 Semantic decomposition . 30 4.3 Levin classes . 32 4.3.1 Beth Levin’s classification . 32 4.3.2 Intersective Levin Classes . 33 4.4 Spanish: verbs of change and verbs of path . 35 4.4.1 Verbs of change . 35 4.4.2 Verbs of path . 37 4.4.3 Discussion . 39 4.5 Lexicographical databases . 40 1 4.5.1 WordNet . 40 4.5.2 VerbNet . 41 4.5.3 FrameNet . 42 5 Subcategorization Acquisition 44 5.1 Evaluation measures . 45 5.1.1 Precision, recall and the F-measure . 45 5.1.2 Types and tokens . 46 5.2 SF acquisition systems . 47 5.2.1 Raw text . -

Experimenting with Pro-Drop in Spanish1

Andrea Pešková Experimenting with Pro-drop in Spanish1 Abstract This paper investigates the omission and expression of pronominal subjects (PS) in Buenos Aires Spanish based on data from a production experiment. The use of PS is a linguistic phenomenon demonstrating that the grammar of a language needs to be considered independently of its usage. Despite the fact that the observed Spanish variety is a consistent pro-drop language with rich verbal agreement, the data from the present study provide evidence for a quite frequent use of overt PS, even in non-focal, non- contrastive and non-ambiguous contexts. This result thus supports previous corpus- based empirical research and contradicts the traditional explanation given by grammarians that overtly realized PS in Spanish are used to avoid possible ambiguities or to mark contrast and emphasis. Moreover, the elicited semi-spontaneous data indicate that the expression of PS is optional; however, this optionality is associated with different linguistic factors. The statistical analysis of the data shows the following ranking of the effects of these factors: grammatical persons > verb semantics > (syntactic) clause type > (semantic) sentence type. 1. Introduction It is well known that Spanish is a pro-drop (“pronoun-dropping”) or null- subject language whose grammar permits the omission of pronominal 1 A preliminary version of this paper was presented at the international conference Variation and typology: New trends in syntactic research in Helsinki (August 2011). I am grateful to the audience for their fruitful discussions and useful commentaries. I would also like to thank the editors, Susann Fischer, Ingo Feldhausen, Christoph Gabriel and the anonymous reviewers for their detailed and helpful comments on an earlier version of this article. -

Phrase Structure Rules, Tree Rewriting, and Other Sources of Recursion Structure Within the NP

Introduction to Transformational Grammar, LINGUIST 601 September 14, 2006 Phrase Structure Rules, Tree Rewriting, and other sources of Recursion Structure within the NP 1 Trees (1) a tree for ‘the brown fox sings’ A ¨¨HH ¨¨ HH B C ¨H ¨¨ HH sings D E the ¨¨HH F G brown fox • Linguistic trees have nodes. The nodes in (1) are A, B, C, D, E, F, and G. • There are two kinds of nodes: internal nodes and terminal nodes. The internal nodes in (1) are A, B, and E. The terminal nodes are C, D, F, and G. Terminal nodes are so called because they are not expanded into anything further. The tree ends there. Terminal nodes are also called leaf nodes. The leaves of (1) are really the words that constitute the sentence ‘the brown fox sings’ i.e. ‘the’, ‘brown’, ‘fox’, and ‘sings’. (2) a. A set of nodes form a constituent iff they are exhaustively dominated by a common node. b. X is a constituent of Y iff X is dominated by Y. c. X is an immediate constituent of Y iff X is immediately dominated by Y. Notions such as subject, object, prepositional object etc. can be defined structurally. So a subject is the NP immediately dominated by S and an object is an NP immediately dominated by VP etc. (3) a. If a node X immediately dominates a node Y, then X is the mother of Y, and Y is the daughter of X. b. A set of nodes are sisters if they are all immediately dominated by the same (mother) node.