Word Recognition in Two Languages and Orthographies: English and Greek

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Empirical Base of Linguistics: Grammaticality Judgments and Linguistic Methodology

UCLA UCLA Previously Published Works Title The empirical base of linguistics: Grammaticality judgments and linguistic methodology Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/05b2s4wg ISBN 978-3946234043 Author Schütze, Carson T Publication Date 2016-02-01 DOI 10.17169/langsci.b89.101 Data Availability The data associated with this publication are managed by: Language Science Press, Berlin Peer reviewed eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California The empirical base of linguistics Grammaticality judgments and linguistic methodology Carson T. Schütze language Classics in Linguistics 2 science press Classics in Linguistics Chief Editors: Martin Haspelmath, Stefan Müller In this series: 1. Lehmann, Christian. Thoughts on grammaticalization 2. Schütze, Carson T. The empirical base of linguistics: Grammaticality judgments and linguistic methodology 3. Bickerton, Derek. Roots of language ISSN: 2366-374X The empirical base of linguistics Grammaticality judgments and linguistic methodology Carson T. Schütze language science press Carson T. Schütze. 2019. The empirical base of linguistics: Grammaticality judgments and linguistic methodology (Classics in Linguistics 2). Berlin: Language Science Press. This title can be downloaded at: http://langsci-press.org/catalog/book/89 © 2019, Carson T. Schütze Published under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 Licence (CC BY 4.0): http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ ISBN: 978-3-946234-02-9 (Digital) 978-3-946234-03-6 (Hardcover) 978-3-946234-04-3 (Softcover) 978-1-523743-32-2 -

CAS LX 522 Syntax I

It is likely… CAS LX 522 IP This satisfies the EPP in Syntax I both clauses. The main DPj I′ clause has Mary in SpecIP. Mary The embedded clause has Vi+I VP is the trace in SpecIP. V AP Week 14b. PRO and control ti This specific instance of A- A IP movement, where we move a likely subject from an embedded DP I′ clause to a higher clause is tj generally called subject raising. I VP to leave Reluctance to leave Reluctance to leave Now, consider: Reluctant has two θ-roles to assign. Mary is reluctant to leave. One to the one feeling the reluctance (Experiencer) One to the proposition about which the reluctance holds (Proposition) This looks very similar to Mary is likely to leave. Can we draw the same kind of tree for it? Leave has one θ-role to assign. To the one doing the leaving (Agent). How many θ-roles does reluctant assign? In Mary is reluctant to leave, what θ-role does Mary get? IP Reluctance to leave Reluctance… DPi I′ Mary Vj+I VP In Mary is reluctant to leave, is V AP Mary is doing the leaving, gets Agent t Mary is reluctant to leave. j t from leave. i A′ Reluctant assigns its θ- Mary is showing the reluctance, gets θ roles within AP as A θ IP Experiencer from reluctant. required, Mary moves reluctant up to SpecIP in the main I′ clause by Spellout. ? And we have a problem: I vP But what gets the θ-role to Mary appears to be getting two θ-roles, from leave, and what v′ in violation of the θ-criterion. -

Vocalic Phonology in New Testament Manuscripts

VOCALIC PHONOLOGY IN NEW TESTAMENT MANUSCRIPTS by DOUGLAS LLOYD ANDERSON (Under the direction of Jared Klein) ABSTRACT This thesis investigates the development of iotacism and the merger of ! and " in Roman and Byzantine manuscripts of the New Testament. Chapter two uses onomastic variation in the manuscripts of Luke to demonstrate that the confusion of # and $ did not become prevalent until the seventh or eighth century. Furthermore, the variations % ~ # and % ~ $ did not manifest themselves until the ninth century, and then only adjacent to resonants. Chapter three treats the unexpected rarity of the confusion of o and " in certain second through fifth century New Testament manuscripts, postulating a merger of o and " in the second century CE in the communities producing the New Testament. Finally, chapter four discusses the chronology of these vocalic mergers to show that the Greek of the New Testament more closely parallels Attic inscriptions than Egyptian papyri. INDEX WORDS: Phonology, New Testament, Luke, Greek language, Bilingual interference, Iotacism, Vowel quantity, Koine, Dialect VOCALIC PHONOLOGY IN NEW TESTAMENT MANUSCRIPTS by DOUGLAS LLOYD ANDERSON B.A., Emory University, 2003 A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the University of Georgia in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree MASTER OF ARTS ATHENS, GEORGIA 2007 © 2007 Douglas Anderson All Rights Reserved VOCALIC PHONOLOGY IN NEW TESTAMENT MANUSCRIPTS by DOUGLAS LLOYD ANDERSON Major Professor: Jared Klein Committee: Erika Hermanowicz Richard -

Archaic Eretria

ARCHAIC ERETRIA This book presents for the first time a history of Eretria during the Archaic Era, the city’s most notable period of political importance. Keith Walker examines all the major elements of the city’s success. One of the key factors explored is Eretria’s role as a pioneer coloniser in both the Levant and the West— its early Aegean ‘island empire’ anticipates that of Athens by more than a century, and Eretrian shipping and trade was similarly widespread. We are shown how the strength of the navy conferred thalassocratic status on the city between 506 and 490 BC, and that the importance of its rowers (Eretria means ‘the rowing city’) probably explains the appearance of its democratic constitution. Walker dates this to the last decade of the sixth century; given the presence of Athenian political exiles there, this may well have provided a model for the later reforms of Kleisthenes in Athens. Eretria’s major, indeed dominant, role in the events of central Greece in the last half of the sixth century, and in the events of the Ionian Revolt to 490, is clearly demonstrated, and the tyranny of Diagoras (c. 538–509), perhaps the golden age of the city, is fully examined. Full documentation of literary, epigraphic and archaeological sources (most of which have previously been inaccessible to an English-speaking audience) is provided, creating a fascinating history and a valuable resource for the Greek historian. Keith Walker is a Research Associate in the Department of Classics, History and Religion at the University of New England, Armidale, Australia. -

Greek and Latin Roots, Prefixes, and Suffixes

GREEK AND LATIN ROOTS, PREFIXES, AND SUFFIXES This is a resource pack that I put together for myself to teach roots, prefixes, and suffixes as part of a separate vocabulary class (short weekly sessions). It is a combination of helpful resources that I have found on the web as well as some tips of my own (such as the simple lesson plan). Lesson Plan Ideas ........................................................................................................... 3 Simple Lesson Plan for Word Study: ........................................................................... 3 Lesson Plan Idea 2 ...................................................................................................... 3 Background Information .................................................................................................. 5 Why Study Word Roots, Prefixes, and Suffixes? ......................................................... 6 Latin and Greek Word Elements .............................................................................. 6 Latin Roots, Prefixes, and Suffixes .......................................................................... 6 Root, Prefix, and Suffix Lists ........................................................................................... 8 List 1: MEGA root list ................................................................................................... 9 List 2: Roots, Prefixes, and Suffixes .......................................................................... 32 List 3: Prefix List ...................................................................................................... -

Language Structure: Phrases “Productivity” a Property of Language • Definition – Language Is an Open System

Language Structure: Phrases “Productivity” a property of Language • Definition – Language is an open system. We can produce potentially an infinite number of different messages by combining elements differently. • Example – Words into phrases. An Example of Productivity • Human language is a communication system that bears some similarities to other animal communication systems, but is also characterized by certain unique features. (24 words) • I think that human language is a communication system that bears some similarities to other animal communication systems, but is also characterized by certain unique features, which are fascinating in and of themselves. (33 words) • I have always thought, and I have spent many years verifying, that human language is a communication system that bears some similarities to other animal communication systems, but is also characterized by certain unique features, which are fascinating in and of themselves. (42 words) • Although mainstream some people might not agree with me, I have always thought… Creating Infinite Messages • Discrete elements – Words, Phrases • Selection – Ease, Meaning, Identity • Combination – Rules of organization Models of Word reCombination 1. Word chains (Markov model) Phrase-level meaning is derived from understanding each word as it is presented in the context of immediately adjacent words. 2. Hierarchical model There are long-distant dependencies between words in a phrase, and these inform the meaning of the entire phrase. Markov Model Rule: Select and concatenate (according to meaning and what types of words should occur next to each other). bites bites bites Man over over over jumps jumps jumps house house house Markov Model • Assumption −Only adjacent words are meaningfully (and lawfully) related. -

Can the Undead Speak?: Language Death As a Matter of (Not) Knowing

Western University Scholarship@Western Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository 1-12-2017 10:15 AM Can the Undead Speak?: Language Death as a Matter of (Not) Knowing Tyler Nash The University of Western Ontario Supervisor Pero, Allan The University of Western Ontario Graduate Program in Theory and Criticism A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the equirr ements for the degree in Master of Arts © Tyler Nash 2017 Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.lib.uwo.ca/etd Part of the Language Interpretation and Translation Commons Recommended Citation Nash, Tyler, "Can the Undead Speak?: Language Death as a Matter of (Not) Knowing" (2017). Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository. 5193. https://ir.lib.uwo.ca/etd/5193 This Dissertation/Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by Scholarship@Western. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository by an authorized administrator of Scholarship@Western. For more information, please contact [email protected]. CAN THE UNDEAD SPEAK?: LANGUAGE DEATH AS A MATTER OF (NOT) KNOWING ABSTRACT This text studies how language death and metaphor algorithmically collude to propagate our intellectual culture. In describing how language builds upon and ultimately necessitates its own ruins to our frustration and subjugation, I define dead language in general and then, following a reading of Benjamin’s “The Task of the Translator,” explore the instance of indexical translation. Inventing the language in pain, a de-signified or designated language located between the frank and the esoteric language theories in the mediaeval of examples of Dante Alighieri and Hildegaard von Bingen, the text acquires the prime modernist example of dead language appropriation in ἀλήθεια and φύσις from the earlier fascistic works of Martin Heidegger. -

24.902F15 Class 13 Pro Versus

Unpronounced subjects 1 We have seen PRO, the subject of infinitives and gerunds: 1. I want [PRO to dance in the park] 2. [PRO dancing in the park] was a good idea 2 There are languages that have unpronounced subjects in tensed clauses. Obviously, English is not among those languages: 3. irθe (Greek) came.3sg ‘he came’ or ‘she came’ 4. *came Languages like Greek, which permit this phenomenon are called “pro-drop” languages. 3 What is the status of this unpronounced subject in pro-drop languages? Is it PRO or something else? Something with the same or different properties from PRO? Let’s follow the convention of calling the unpronounced subject in tensed clauses “little pro”, as opposed to “big PRO”. What are the differences between pro and PRO? 4 -A Nominative NP can appear instead of pro. Not so for PRO: 5. i Katerina irθe the Katerina came.3sg ‘Katerina came’ 6. *I hope he/I to come 7. *he to read this book would be great 5 -pro can refer to any individual as long as Binding Condition B is respected. That is, pro is not “controlled”. Not so for OC PRO. 8. i Katerinak nomizi oti prok/m irθe stin ora tis the K thinks that came on-the time her ‘Katerinak thinks that shek/m /hem came on time’ 9. Katerinak wants [PROk/*m to leave] 6 -pro can yield sloppy or strict readings under ellipsis, exactly like pronouns. Not so OC PRO. 10. i Katerinak nomizi oti prok/m irθe stin ora tis the K thinks that came on-the time her ke i Maria episis and the Maria also ‘Katerinak thinks that shek came on time and Maria does too’ =…Maria thinks that Katerina came on time strict …Maria thinks that Maria came on time sloppy 7 11. -

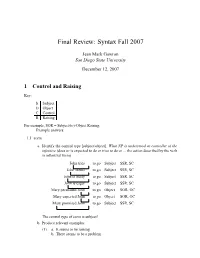

Final Review: Syntax Fall 2007

Final Review: Syntax Fall 2007 Jean Mark Gawron San Diego State University December 12, 2007 1 Control and Raising Key: S Subject O Object C Control R Raising For example, SOR = Subject(to)-Object Raising. Example answers: 1.1 seem a. Identify the control type [subject/object]. What NP is understood as controller of the infinitive (does or is expected to do or tries to do or ... the action described by the verb in infinitival form) John tries to go Subject SSR, SC John seems to go Subject SSR, SC John is likely to go Subject SSR, SC John is eager to go Subject SSR, SC Mary persuaded John to go Object SOR, OC Mary expected John to go Object SOR, OC Mary promised John to go Subject SSR, SC The control type of seem is subject! b. Produce relevant examples: (1) a. Itseemstoberaining b. There seems to be a problem c. The chips seems to be down. d. It seems to be obvious that John is a fool. e. The police seem to have caught the burglar. f. The burglar seems to have been caught by the police. c. Example construction i. Construct embedded clause: (a) itrains. Simpleexample;dummysubject * John rains Testing dummy subjecthood ittorain Putintoinfinitivalform ii. Embed (a) ∆ seem [CP it to rain] Embed under seem [ctd.] it seem [CP t torain] Moveit— it seems [CP t to rain] Add tense, agreement (to main verb) d. Other examples (b) itisraining. Alternativeexample;dummysubject *Johnisraining Testingdummysubjecthood ittoberaining Putintoinfinitivalform ∆ seem [CP it to be raining] Embed under seem it seem [CP t toberaining] Moveit— it seems [CP t to be raining] Add tense, agreement (to main verb) (c) Thechipsaredown. -

How Do Speakers of a Language with a Transparent Orthographic System

languages Article How Do Speakers of a Language with a Transparent Orthographic System Perceive the L2 Vowels of a Language with an Opaque Orthographic System? An Analysis through a Battery of Behavioral Tests Georgios P. Georgiou Department of Languages and Literature, University of Nicosia, Nicosia 2417, Cyprus; [email protected] Abstract: Background: The present study aims to investigate the effect of the first language (L1) orthography on the perception of the second language (L2) vowel contrasts and whether orthographic effects occur at the sublexical level. Methods: Fourteen adult Greek learners of English participated in two AXB discrimination tests: one auditory and one orthography test. In the auditory test, participants listened to triads of auditory stimuli that targeted specific English vowel contrasts embedded in nonsense words and were asked to decide if the middle vowel was the same as the first or the third vowel by clicking on the corresponding labels. The orthography test followed the same procedure as the auditory test, but instead, the two labels contained grapheme representations of the target vowel contrasts. Results: All but one vowel contrast could be more accurately discriminated in the auditory than in the orthography test. The use of nonsense words in the elicitation task Citation: Georgiou, Georgios P. 2021. eradicated the possibility of a lexical effect of orthography on auditory processing, leaving space for How Do Speakers of a Language with the interpretation of this effect on a sublexical basis, primarily prelexical and secondarily postlexical. a Transparent Orthographic System Conclusions: L2 auditory processing is subject to L1 orthography influence. Speakers of languages Perceive the L2 Vowels of a Language with transparent orthographies such as Greek may rely on the grapheme–phoneme correspondence to with an Opaque Orthographic System? An Analysis through a decode orthographic representations of sounds coming from languages with an opaque orthographic Battery of Behavioral Tests. -

Experimenting with Pro-Drop in Spanish1

Andrea Pešková Experimenting with Pro-drop in Spanish1 Abstract This paper investigates the omission and expression of pronominal subjects (PS) in Buenos Aires Spanish based on data from a production experiment. The use of PS is a linguistic phenomenon demonstrating that the grammar of a language needs to be considered independently of its usage. Despite the fact that the observed Spanish variety is a consistent pro-drop language with rich verbal agreement, the data from the present study provide evidence for a quite frequent use of overt PS, even in non-focal, non- contrastive and non-ambiguous contexts. This result thus supports previous corpus- based empirical research and contradicts the traditional explanation given by grammarians that overtly realized PS in Spanish are used to avoid possible ambiguities or to mark contrast and emphasis. Moreover, the elicited semi-spontaneous data indicate that the expression of PS is optional; however, this optionality is associated with different linguistic factors. The statistical analysis of the data shows the following ranking of the effects of these factors: grammatical persons > verb semantics > (syntactic) clause type > (semantic) sentence type. 1. Introduction It is well known that Spanish is a pro-drop (“pronoun-dropping”) or null- subject language whose grammar permits the omission of pronominal 1 A preliminary version of this paper was presented at the international conference Variation and typology: New trends in syntactic research in Helsinki (August 2011). I am grateful to the audience for their fruitful discussions and useful commentaries. I would also like to thank the editors, Susann Fischer, Ingo Feldhausen, Christoph Gabriel and the anonymous reviewers for their detailed and helpful comments on an earlier version of this article. -

The Impact of Orthography on the Acquisition of L2 Phonology:1

Coutsougera, The Impact of Orthography on the Acquisition of L2 Phonology:1 The impact of orthography on the acquisition of L2 phonology: inferring the wrong phonology from print Photini Coutsougera, University of Cyprus 1 The orthographic systems of English and Greek The aim of this study is to investigate how the deep orthography of English influences the acquisition of L2 English phonetics/phonology by L1 Greek learners, given that Greek has a shallow orthography. Greek and English deploy two fundamentally different orthographies. The Greek orthography, despite violating one-letter-to-one-phoneme correspondence, is shallow or transparent. This is because although the Greek orthographic system has a surplus of letters/digraphs for vowel sounds (e.g. sound /i/ is represented in six different ways in the orthography); each letter/digraph has one reading. There are very few other discrepancies between letters and sounds, which are nevertheless handled by specific, straightforward rules. As a result, there is only one possible way of reading a written form. The opposite, however, does not hold, i.e. a speaker of Greek cannot predict the spelling of a word when provided with the pronunciation. In contrast, as often cited in the literature, English has a deep or non transparent orthography since it allows for the same letter to represent more than one sound or for the same sound to be represented by more than one letter. Other discrepancies between letters and sounds - also well reported or even overstated in the literature - are of rather lesser importance (e.g. silent letters existing mainly for historical reasons etc).