A New Role for Linguistic Philosophy in Education with an Application to the Field of Learning Disability

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Empirical Base of Linguistics: Grammaticality Judgments and Linguistic Methodology

UCLA UCLA Previously Published Works Title The empirical base of linguistics: Grammaticality judgments and linguistic methodology Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/05b2s4wg ISBN 978-3946234043 Author Schütze, Carson T Publication Date 2016-02-01 DOI 10.17169/langsci.b89.101 Data Availability The data associated with this publication are managed by: Language Science Press, Berlin Peer reviewed eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California The empirical base of linguistics Grammaticality judgments and linguistic methodology Carson T. Schütze language Classics in Linguistics 2 science press Classics in Linguistics Chief Editors: Martin Haspelmath, Stefan Müller In this series: 1. Lehmann, Christian. Thoughts on grammaticalization 2. Schütze, Carson T. The empirical base of linguistics: Grammaticality judgments and linguistic methodology 3. Bickerton, Derek. Roots of language ISSN: 2366-374X The empirical base of linguistics Grammaticality judgments and linguistic methodology Carson T. Schütze language science press Carson T. Schütze. 2019. The empirical base of linguistics: Grammaticality judgments and linguistic methodology (Classics in Linguistics 2). Berlin: Language Science Press. This title can be downloaded at: http://langsci-press.org/catalog/book/89 © 2019, Carson T. Schütze Published under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 Licence (CC BY 4.0): http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ ISBN: 978-3-946234-02-9 (Digital) 978-3-946234-03-6 (Hardcover) 978-3-946234-04-3 (Softcover) 978-1-523743-32-2 -

CAS LX 522 Syntax I

It is likely… CAS LX 522 IP This satisfies the EPP in Syntax I both clauses. The main DPj I′ clause has Mary in SpecIP. Mary The embedded clause has Vi+I VP is the trace in SpecIP. V AP Week 14b. PRO and control ti This specific instance of A- A IP movement, where we move a likely subject from an embedded DP I′ clause to a higher clause is tj generally called subject raising. I VP to leave Reluctance to leave Reluctance to leave Now, consider: Reluctant has two θ-roles to assign. Mary is reluctant to leave. One to the one feeling the reluctance (Experiencer) One to the proposition about which the reluctance holds (Proposition) This looks very similar to Mary is likely to leave. Can we draw the same kind of tree for it? Leave has one θ-role to assign. To the one doing the leaving (Agent). How many θ-roles does reluctant assign? In Mary is reluctant to leave, what θ-role does Mary get? IP Reluctance to leave Reluctance… DPi I′ Mary Vj+I VP In Mary is reluctant to leave, is V AP Mary is doing the leaving, gets Agent t Mary is reluctant to leave. j t from leave. i A′ Reluctant assigns its θ- Mary is showing the reluctance, gets θ roles within AP as A θ IP Experiencer from reluctant. required, Mary moves reluctant up to SpecIP in the main I′ clause by Spellout. ? And we have a problem: I vP But what gets the θ-role to Mary appears to be getting two θ-roles, from leave, and what v′ in violation of the θ-criterion. -

Greek and Latin Roots, Prefixes, and Suffixes

GREEK AND LATIN ROOTS, PREFIXES, AND SUFFIXES This is a resource pack that I put together for myself to teach roots, prefixes, and suffixes as part of a separate vocabulary class (short weekly sessions). It is a combination of helpful resources that I have found on the web as well as some tips of my own (such as the simple lesson plan). Lesson Plan Ideas ........................................................................................................... 3 Simple Lesson Plan for Word Study: ........................................................................... 3 Lesson Plan Idea 2 ...................................................................................................... 3 Background Information .................................................................................................. 5 Why Study Word Roots, Prefixes, and Suffixes? ......................................................... 6 Latin and Greek Word Elements .............................................................................. 6 Latin Roots, Prefixes, and Suffixes .......................................................................... 6 Root, Prefix, and Suffix Lists ........................................................................................... 8 List 1: MEGA root list ................................................................................................... 9 List 2: Roots, Prefixes, and Suffixes .......................................................................... 32 List 3: Prefix List ...................................................................................................... -

Language Structure: Phrases “Productivity” a Property of Language • Definition – Language Is an Open System

Language Structure: Phrases “Productivity” a property of Language • Definition – Language is an open system. We can produce potentially an infinite number of different messages by combining elements differently. • Example – Words into phrases. An Example of Productivity • Human language is a communication system that bears some similarities to other animal communication systems, but is also characterized by certain unique features. (24 words) • I think that human language is a communication system that bears some similarities to other animal communication systems, but is also characterized by certain unique features, which are fascinating in and of themselves. (33 words) • I have always thought, and I have spent many years verifying, that human language is a communication system that bears some similarities to other animal communication systems, but is also characterized by certain unique features, which are fascinating in and of themselves. (42 words) • Although mainstream some people might not agree with me, I have always thought… Creating Infinite Messages • Discrete elements – Words, Phrases • Selection – Ease, Meaning, Identity • Combination – Rules of organization Models of Word reCombination 1. Word chains (Markov model) Phrase-level meaning is derived from understanding each word as it is presented in the context of immediately adjacent words. 2. Hierarchical model There are long-distant dependencies between words in a phrase, and these inform the meaning of the entire phrase. Markov Model Rule: Select and concatenate (according to meaning and what types of words should occur next to each other). bites bites bites Man over over over jumps jumps jumps house house house Markov Model • Assumption −Only adjacent words are meaningfully (and lawfully) related. -

Paul Rastall, a Linguistic Philosophy of Language, Lewiston, Queenston

Linguistica ONLINE. Published: July 10, 2009 http://www.phil.muni.cz/linguistica/art/mulder/mul-001.pdf ISSN 1801-5336 PAUL RASTALL: A LINGUISTIC PHILOSOPHY OF LANGUAGE, LAMPETER – LEWISTON, 2000[*] review article by Jan W. F. Mulder (University of St. Andrews, UK) Introductory note by Aleš Bičan In 2006 I happened to have a short e-mail conversation with Jan Mulder. I asked him for off-prints of his articles, as some of them were rather hard to find. He was so generous to send me, by regular post, a huge packet of them. It took me some time to realize that some of the included writings had never been published. One of them was a manuscript (type- script) of a discussion of a book by Paul Rastall, a former student of his, which was pub- lished in 2000 by The Edwin Press. I naturally contacted Paul Rastall and asked him about the article. He was not aware of it but supported my idea of having it published in Linguis- tica ONLINE. He consequently spoke to Mulder who welcomed the idea and granted the permission. The article below is thus published for the first time. It should be noted, how- ever, that Jan Mulder has not seen its final form. The text is reproduced here as it appears in the manuscript. I have only corrected a few typographical errors here and there. The only significant change is the inclusion of a list of references. Mulder refers to a number of works, but bibliographical information is not pro- vided. I have tried to list all that are mentioned in the article. -

CRITICAL NOTICE Why We Need Ordinary Language Philosophy

CRITICAL NOTICE Why We Need Ordinary Language Philosophy Sandra Laugier, Translated by Daniela Ginsberg, The University of Chicago Press, Chicago, 2013, pp. 168, £ 24.50. ISBN-13: 978-0-226-47054-2 (cloth). Reviewed by Derek A. McDougall Originally published in French in the year 2000, the English version of Sandra Laugier’s short book of 10 Chapters plus an Introduction and Conclusion, has a 7 page Preface, 9 pages of Notes, a brief Bibliography and 121 pages of actual text. The reading of Wittgenstein and Austin that she provides is distinctly Cavellian in character. Indeed, Stanley Cavell in a dust-cover quote, remarks that her work is already influential in France and Italy, exciting as it does a new interest in ‘language conceived not only as a cognitive capacity but also as used, and meant, as part of our form of life’. Cavell goes on to say that this new translation is not merely welcome but indispensable, and has at least the capacity to alter prevailing views about the philosophy of language, so affecting what we have come to think of as the ‘analytic-continental divide’. Toril Moi of Duke Uni., in another dust-cover quote, states that Laugier’s reading of Wittgenstein-Austin-Cavell shows how their claim that ‘to speak about language is to speak about the world is an antimetaphysical revolution in philosophy that tranforms our understanding of epistemology and ethics.’ She concludes with the thought that anyone who wishes to understand what ‘ordinary language philosophy’ means today should read this book. This is a large claim to make, and anyone who is inclined to read Wittgenstein and Austin strictly in their own terms, and with their own avowed intentions - where discernible - steadily in view, is almost bound to conclude that it is simply not true. -

The Pragmatic Turn in Philosophy

Introduction n recent years the classical authors of Anglo-Saxon pragmatism have gar- Inered a renewed importance in international philosophical circles. In the aftermath of the linguistic turn, philosophers such as Charles S. Peirce, William James, George H. Mead, Ferdinand C. S. Schiller, and John Dewey are being reread alongside, for example, recent postmodern and deconstructivist thought as alternatives to a traditional orientation toward the concerns of a represen- tationalist epistemology. In the context of contemporary continental thought, the work of Jacques Derrida, Jean-Francois Lyotard, and Gilles Deleuze comprises just a few examples of a culturewide assault on a metaphysical worldview premised on what Michel Foucault called the empirico-transcendental doublet, and presents a wealth of potential exchange with the pragmatist critique of representationalism. In both cases, aspects of pragmatist thought are being used to add flexibility to the conceptual tools of modern philoso- phy, in order to promote a style of philosophizing more apt to dealing with the problems of everyday life. The hope for a pragmatic “renewing of phi- losophy” (Putnam) evidenced in these trends has led to an analytic reexami- nation of some of the fundamental positions in modern continental thought as well, and to a recognition of previously unacknowledged or underappreciated pragmatic elements in thinkers like Kant, Hegel, Nietzsche, Heidegger, and Wittgenstein. Within the current analytic discussions, a wide spectrum of differing and at times completely heterogeneous forms of neopragmatism can be distinguished, which for heuristic purposes can be grouped into two general categories according to the type of discursive strategy employed. The first of these consists in a conscious inflation of the concept of pragmatism in order to establish it as widely as possible within the disciplinary discourse of philosophy. -

24.902F15 Class 13 Pro Versus

Unpronounced subjects 1 We have seen PRO, the subject of infinitives and gerunds: 1. I want [PRO to dance in the park] 2. [PRO dancing in the park] was a good idea 2 There are languages that have unpronounced subjects in tensed clauses. Obviously, English is not among those languages: 3. irθe (Greek) came.3sg ‘he came’ or ‘she came’ 4. *came Languages like Greek, which permit this phenomenon are called “pro-drop” languages. 3 What is the status of this unpronounced subject in pro-drop languages? Is it PRO or something else? Something with the same or different properties from PRO? Let’s follow the convention of calling the unpronounced subject in tensed clauses “little pro”, as opposed to “big PRO”. What are the differences between pro and PRO? 4 -A Nominative NP can appear instead of pro. Not so for PRO: 5. i Katerina irθe the Katerina came.3sg ‘Katerina came’ 6. *I hope he/I to come 7. *he to read this book would be great 5 -pro can refer to any individual as long as Binding Condition B is respected. That is, pro is not “controlled”. Not so for OC PRO. 8. i Katerinak nomizi oti prok/m irθe stin ora tis the K thinks that came on-the time her ‘Katerinak thinks that shek/m /hem came on time’ 9. Katerinak wants [PROk/*m to leave] 6 -pro can yield sloppy or strict readings under ellipsis, exactly like pronouns. Not so OC PRO. 10. i Katerinak nomizi oti prok/m irθe stin ora tis the K thinks that came on-the time her ke i Maria episis and the Maria also ‘Katerinak thinks that shek came on time and Maria does too’ =…Maria thinks that Katerina came on time strict …Maria thinks that Maria came on time sloppy 7 11. -

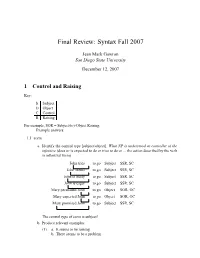

Final Review: Syntax Fall 2007

Final Review: Syntax Fall 2007 Jean Mark Gawron San Diego State University December 12, 2007 1 Control and Raising Key: S Subject O Object C Control R Raising For example, SOR = Subject(to)-Object Raising. Example answers: 1.1 seem a. Identify the control type [subject/object]. What NP is understood as controller of the infinitive (does or is expected to do or tries to do or ... the action described by the verb in infinitival form) John tries to go Subject SSR, SC John seems to go Subject SSR, SC John is likely to go Subject SSR, SC John is eager to go Subject SSR, SC Mary persuaded John to go Object SOR, OC Mary expected John to go Object SOR, OC Mary promised John to go Subject SSR, SC The control type of seem is subject! b. Produce relevant examples: (1) a. Itseemstoberaining b. There seems to be a problem c. The chips seems to be down. d. It seems to be obvious that John is a fool. e. The police seem to have caught the burglar. f. The burglar seems to have been caught by the police. c. Example construction i. Construct embedded clause: (a) itrains. Simpleexample;dummysubject * John rains Testing dummy subjecthood ittorain Putintoinfinitivalform ii. Embed (a) ∆ seem [CP it to rain] Embed under seem [ctd.] it seem [CP t torain] Moveit— it seems [CP t to rain] Add tense, agreement (to main verb) d. Other examples (b) itisraining. Alternativeexample;dummysubject *Johnisraining Testingdummysubjecthood ittoberaining Putintoinfinitivalform ∆ seem [CP it to be raining] Embed under seem it seem [CP t toberaining] Moveit— it seems [CP t to be raining] Add tense, agreement (to main verb) (c) Thechipsaredown. -

Experimenting with Pro-Drop in Spanish1

Andrea Pešková Experimenting with Pro-drop in Spanish1 Abstract This paper investigates the omission and expression of pronominal subjects (PS) in Buenos Aires Spanish based on data from a production experiment. The use of PS is a linguistic phenomenon demonstrating that the grammar of a language needs to be considered independently of its usage. Despite the fact that the observed Spanish variety is a consistent pro-drop language with rich verbal agreement, the data from the present study provide evidence for a quite frequent use of overt PS, even in non-focal, non- contrastive and non-ambiguous contexts. This result thus supports previous corpus- based empirical research and contradicts the traditional explanation given by grammarians that overtly realized PS in Spanish are used to avoid possible ambiguities or to mark contrast and emphasis. Moreover, the elicited semi-spontaneous data indicate that the expression of PS is optional; however, this optionality is associated with different linguistic factors. The statistical analysis of the data shows the following ranking of the effects of these factors: grammatical persons > verb semantics > (syntactic) clause type > (semantic) sentence type. 1. Introduction It is well known that Spanish is a pro-drop (“pronoun-dropping”) or null- subject language whose grammar permits the omission of pronominal 1 A preliminary version of this paper was presented at the international conference Variation and typology: New trends in syntactic research in Helsinki (August 2011). I am grateful to the audience for their fruitful discussions and useful commentaries. I would also like to thank the editors, Susann Fischer, Ingo Feldhausen, Christoph Gabriel and the anonymous reviewers for their detailed and helpful comments on an earlier version of this article. -

Philosophy of Language in the Twentieth Century Jason Stanley Rutgers University

Philosophy of Language in the Twentieth Century Jason Stanley Rutgers University In the Twentieth Century, Logic and Philosophy of Language are two of the few areas of philosophy in which philosophers made indisputable progress. For example, even now many of the foremost living ethicists present their theories as somewhat more explicit versions of the ideas of Kant, Mill, or Aristotle. In contrast, it would be patently absurd for a contemporary philosopher of language or logician to think of herself as working in the shadow of any figure who died before the Twentieth Century began. Advances in these disciplines make even the most unaccomplished of its practitioners vastly more sophisticated than Kant. There were previous periods in which the problems of language and logic were studied extensively (e.g. the medieval period). But from the perspective of the progress made in the last 120 years, previous work is at most a source of interesting data or occasional insight. All systematic theorizing about content that meets contemporary standards of rigor has been done subsequently. The advances Philosophy of Language has made in the Twentieth Century are of course the result of the remarkable progress made in logic. Few other philosophical disciplines gained as much from the developments in logic as the Philosophy of Language. In the course of presenting the first formal system in the Begriffsscrift , Gottlob Frege developed a formal language. Subsequently, logicians provided rigorous semantics for formal languages, in order to define truth in a model, and thereby characterize logical consequence. Such rigor was required in order to enable logicians to carry out semantic proofs about formal systems in a formal system, thereby providing semantics with the same benefits as increased formalization had provided for other branches of mathematics. -

Discuss. Ludwig Wittgenstein's “Tractatus Logico Philosophicus

“The limits of my language mean the limits of my world.” Discuss. Ludwig Wittgenstein’s “Tractatus Logico Philosophicus,” published in 1921, was a pivotal work of the early 20th Century’s ‘linguistic turn’- a time in which the importance of language was being investigated across many academic disciplines. The aim of Wittgenstein’s “Tractatus” is “to draw limit to thought”;1 he argues that for something to exist in the world- either imagined or physical- it must be possible to think of it.2 Therefore, the use of language to express thought is a means to map the boundaries of reality. The interaction between language and thought that Wittgenstein advocated was later labelled ‘linguistic relativism’, following the work of Edward Sapir and Benjamin Whorf. However, two key aspects of Wittgenstein’s theory: that language is capable of both limiting the thoughts we can have and influencing the nature of these thoughts, will be scrutinised below to demonstrate how the interaction between language and thoughts is substantially more minimal than Wittgenstein suggested. In addition, the ever-changing “limits” of both language and the world, alongside the problem of meaning, will be investigated in order to show how the world limits language, rather than vice versa. George Orwell’s dystopian classic “1984”, poses questions concerning the nature of a language “designed not to extend but to diminish the range of thought” through the “reduction of vocabulary.”3 As Wittgenstein argues, for something to potentially exist in the world, it must be within the range of thought, which he believes to be reflected through the range of language.