How a Steam Engine Works, by Archibald Williams

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Building a Small Horizontal Steam Engine

Building a Small Horizontal Steam Engine The front cylinder head is a pipe cap, THE small engine described in this the exterior of which is turned to pre- article was built by the writer in sent a more pleasing appearance, and his spare time—about an hour a day for drilled and threaded to receive the stuff- four months—and drives the machinery ing box, Fig. 2. The distance between in a small shop. At 40-lb. gauge pres- the edge of the front-end steam port and sure, the engine runs at 150 r.p.m., under the inner side of the cap, when screwed full load, and delivers a little over .4 home, should be much less than that brake horsepower. A cast steam chest, shown, not over ¼ in., for efficiency, and with larger and more direct steam ports, the same at the rear end. When the to reduce condensation losses; less clear- cap has been permanently screwed on ance in the cylinder ends, and larger the cylinder, one side is flattened, as bearing surfaces in several places, would shown, on the shaper or grinder, and the bring the efficiency of the engine up to a steam ports laid out and drilled. It would much higher point than this. In the be a decided advantage to make these writer's case, however, the engine is de- ports as much larger than given as is livering ample power for the purpose to possible, as the efficiency with ½-in. ports which it is applied, and consequently is far below what it might be. -

WSA Engineering Branch Training 3

59 RECIPROCATING STEAM ENGINES Reciprocating type main engines have been used to propel This is accomplished by the guide and slipper shown in the ships, since Robert Fulton first installed one in the Clermont in drawing. 1810. The Clermont's engine was a small single cylinder affair which turned paddle wheels on the side of the ship. The boiler was only able to supply steam to the engine at a few pounds pressure. Since that time the reciprocating engine has been gradually developed into a much larger and more powerful engine of several cylinders, some having been built as large as 12,000 horsepower. Turbine type main engines being much smaller and more powerful were rapidly replacing reciprocating engines, when the present emergency made it necessary to return to the installation of reciprocating engines in a large portion of the new ships due to the great demand for turbines. It is one of the most durable and reliable type engines, providing it has proper care and lubrication. Its principle of operation consists essentially of a cylinder in which a close fitting piston is pushed back and forth or up and down according to the position of the cylinder. If steam is admitted to the top of the cylinder, it will expand and push the piston ahead of it to the bottom. Then if steam is admitted to the bottom of the cylinder it will push the piston back up. This continual back and forth movement of the piston is called reciprocating motion, hence the name, reciprocating engine. To turn the propeller the motion must be changed to a rotary one. -

OGV Slide Valve Low-Load Emissions Evaluation

OGV Slide Valve Low-Load Emissions Evaluation CONVENTIONAL SLIDE FUEL VALVE FUEL VALVE Technology Manufacturer MAN Diesel & Turbo A/S Co-Participants MAN Diesel & Turbo A/S Mitsui Engineering & Shipbuilding Co, LTD Starcrest Consulting Group, LLC Background In 2008, the Port of Los Angeles and the Port of Long Beach participated in a demonstration of slide-type fuel valves to quantify their effectiveness as an emissions reduction retrofit technology for ocean-going vessels (OGVs) equipped with Tier 0 and Tier 1 two-stroke diesel main engines1. The demonstration was conducted aboard the APL Singapore. This new type of OGV main engine fuel valve is designed to improve combustion properties by eliminating sac volume (i.e., fuel drips) at the valve nozzle. The elimination of the sac volume results in lower fuel oil consumption. In addition, slide valve nozzles incorporate an optimized spray pattern designed to improve the combustion process - this is intended to reduce overall emissions, including hydrocarbon, NOx and particulate matter. The visible smoke level is also greatly reduced as a result of the improved combustion. The manufacturer, MAN Diesel & Turbo A/S (MDT), had previously published data suggesting slide valves offered a potential for a 30% reduction in NOx emissions and 25% reduction in DPM emissions when the technology is optimized in new engines. The results from the 2008 APL Singapore slide valve retrofit demonstration, although ultimately inconclusive, seemed to suggest that the use of slide valves as an OGV main engine retrofit technology might not provide the level of emission reductions originally anticipated. In addition to the APL data, new information provided by the manufacturer also indicated that potential benefits from slide valves could be eroded as engine load is reduced. -

Starting & Tuning the New TRX2.5 Engine

Starting & Tuning the New TRX2.5 Engine Starting & Tuning the New TRX2.5 Engine By Steve Slayden* Now that the amazing new T-Maxx 2.5 truck has been released and is in the hands of many excited and enthusiastic owners, I thought it was time to give some important tips on starting, breaking-in and tuning this hot little monster for maximum performance. This piece will be useful for anyone who has just purchased a new T-Maxx 2.5 and also those of you who are looking into getting one of your own. Some of the tips may even be helpful to some of you T-Maxx veterans out there as well, so grab your gear and let's get started. Tools and Accessories: As with all Traxxas RTR vehicles the T-Maxx comes pre-assembled with radio gear already installed. The instruction packet included in the box contains some important tools and accessories that can be used to perform minor maintenance tasks and repairs. Basic hand tools such as screwdrivers, pliers, Starting & Tuning the New TRX2.5 Engine wire cutters, etc. will be necessary to perform major disassembly of the truck. There will also be some accessory items needed to keep your truck up and running. I'll run down a list of important and handy items that will make working on and tuning your new Maxx a much more pleasurable experience. Some of the tools listed below are not absolutely necessary but will make tuning quicker and easier. I've listed only the tools that would be useful for this particular segment. -

THROWBACK MODELLER September/October 2019 Issue 11 Continuing the Tradition…

THROWBACK MODELLER September/October 2019 Issue 11 Continuing the tradition…... It’s rude to ask a lady……. Exeter exhortations Always a Princess at heart 16MM HERITAGE LOCOMOTIVE OWNERS AND OPERATORS Throwback Modeller ASSOCIATION ISSUE 11 SEPTEMBER/O CTOBER 2019 I S S U E 1 1 Welcome to Issue Eleven No, no, no I was driving to only thing that re- work earlier this week listen- mains is my embar- ing to the radio and Zoe Ball rassment (and a hiked was telling me how many insurance premium). I weekends left until Christ- was most anxious to mas. What! Another year get sorted to get up to that’s flown by. I was drawn the Elsecar show - I up short by the fact that made it and had we’ve lost three 16mm char- planned to quietly run acters in the last two my Archangel Moel months, Jim, John and Brian. Tryfan. Despite my John had made his mark best efforts I couldn’t get On the subject of exhibitions through his models. Jim was her to run, and quiet went and gatherings we did hold a instrumental in hosting the out the window as the safety wet and windswept Heritage early garden meetings, es- valve lifted on the stalled Open day here again in Der- tablishing and growing the engine. by mid August (wet and early Association. Brian windswept in high sum- My guardian angel stepped made a different contribu- mer—grrrrr). It was a se- in and I’m looking forward to tion he was on the Associa- date affair as given the dropping down to see him tion Board for some of the weather it wasn’t a good and collecting the repaired time while I was Chair and outlook for people travelling loco in time for it’s next pub- then re-joined the Board distances. -

Steam Engines of Which We Have Any Knowledge Were

A T H OROUGH AND PR ACT I CAL PR ESENT AT I ON OF MODER N ST EAM ENGI NE PR ACT I CE LLEWELLY DY N . I U M . E . V i P O F S S O O F X P M L G G P U DU U V S Y R E R E ERI ENTA EN INEERIN , R E NI ER IT AM ERICAN S O CIETY O F M ECH ANI C A L EN G INEERS I LL US T RA T ED AM ER ICA N T ECH N ICA L SOCIET Y C H ICAGO 19 17 CO PY GH 19 12 19 17 B Y RI T , , , AM ER ICA N T ECH N ICAL SOCIET Y CO PY RIG H TE D IN G REAT B RITAI N A L L RIGH TS RE S ERV E D 4 8 1 8 9 6 "GI. A INT RO DUCT IO N n m n ne w e e b e the ma es o ss H E moder stea e gi , h th r it j tic C rli , which so silently o pe rates the m assive e le ctric generators in f r mun a owe an s o r the an o o mo e w one o ou icip l p r pl t , gi t l c tiv hich t m es an o u omman s our uns n e pulls the Limited a sixty il h r , c d ti t d n And t e e m o emen is so f ee and e fe in admiratio . -

Steam Engine Collection

STEAM ENGINE COLLECTION The New England Museum of Wireless And Steam Frenchtown Road ~ East Greenwich, R.I. International Mechanical Engineering Heritage Collection Designated September 12, 1992 The American Society of Mechanical Engineers INTRODUCTION It has been said that an operating steam engine is ‘visual music’. The New England Museum of Wireless and Steam provides the steam engine enthusiast, the mechanical engineer and the public at large with an opportunity to experience the ‘music’ when the engines are in steam. At the same time they can appreciate the engineering skills of those who designed the engines. The New England Museum of Wireless and Steam is unusual among museums in its focus on one aspect of mechanical engineering history, namely, the history of the steam engine. It is especially rich in engines manufactured in Rhode Island, a state which has had an influence on the history of the steam engine in the United States out of all proportion to its size and population. Many of the great names in the design and manufacture of steam engines received their training in Rhode Island, most particularly in the shops of the Corliss Steam Engine Co. in Providence. George H. Corliss, an important contributor to steam engine technology, founded his company in Providence in 1846. Engines that used his patent valve gear were built in large numbers by the Corliss company, and by others, both in the United States and abroad, either under license or in various modified forms once the Corliss patent expired in 1870. The New England Museum of Wireless and Steam is particularly fortunate in preserving an example of a Corliss engine built by the Corliss Steam Engine Company. -

Accucraft PRR E6s Atlantic

Accucraft PRR E6s Atlantic Manual for Butane and Alcohol versions #1794 PRR E6s first production model #460 PRR E6s last production model Instruction Manual PRR E6s Atlantic Note: Please read the entire manual prior to operation Unpacking Remove inner wooden boxes from the shipping carton, open and remove the foam padding. The locomotive is bolted down to the crate, use a long phillips screwdriver and a wrench to remove the 4 bolts. Lift the plate and locomotive form the case. Place the board on a hard surface and using a razor knife cut along the board edge. Carefully pull off the tape and plastic from the locomotive. Discard all tape and plastic. The tender is housed in foam and paper. Simply lift out being careful of the ladder and lamps General Information Operating a live steam model is different than a electrically powered version. It is a hands on interactive model. Never leave any working engines unattended once the burner is lit or if the locomotive under way. Always know where and how the locomotive is operating including the boiler water levels. • Always read and understand the manual prior to operation for the first time • Always maintain the lubrication on the motion parts and lubricator as it is designed for extended run times. The lubricator will last for about 45-60mins • Never let the engine run completely out of water – if the locomotive suddenly stops and there is still pressure or if the glass is empty shut down the burner. DO NOT ADD WATER TO A HOT EMPTY BOILER • When filing the butane gas tank keep away from any open flame or passing by locomotives, especially Alcohol fired locomotives. -

2. ABY I.E., UNITED STATES PATENT OFRICR

J. F. FRITZ. DRAINING APPARATUS FORTUNNES, &c, APPLICATION FLED MAR. 15, 1917, Patented Nov. 27, 1917. W I | Lil N S % a-II-II dist SY % as Zig WTOR 2. ABY i.e., UNITED STATES PATENT OFRICR. 503 AFS E. F.E.2, OR 22 O3, SEAN ID, O3.3 g (0., DEASE G APPARATUS FORTUNNES, as 1243,812. Speciacation of letters atoga, Paterated. Now. 23, 1912. Applicationaled March 15, 1917. Serial No. 55,046. Zo a whom 3 gray concery plate, pistons 6 in the cylinders and pro Be it known that I, JoHAN F. FRrtz, a vided with piston rods moving cross subject of the King of Sweden, who have heads 8 along guides 9 on the frame 3 declared my intention to become a citizen holding the bearings or journal boxes 3. S5 of the United States, residing at Portland, From said cross-heads extend connecting in the county of Multnomah and State of rods 10, by which cranks 11 of the engine Oregon, have invented a new and useful shaft 12 are operated. Said cranks are Draining Apparatus for Tunnels, &c., of arranged in opposite radial directions and which the following is a specification. the shaft is provided with an efficient fly 30 My invention relates to pumping ma wheel 13 for carrying the cranks over their chinery for the removal of water from tun highest and lowest points. The shaft, is nels, mines and ditches, especially while also provided at one end with a pulley 14 they are under construction. for the transmission of power to otherma The object is to provide a cheap, simple chinery (not shown). -

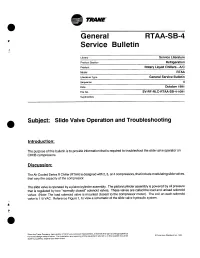

CHHB Slide Valve Operation and Troubleshooting

TRANE- q Genera RTAA-SB-4 lit l Service Bulletin . Library S ervice Literature Prod uct Section Refrigeration Product Rotary Liqu id Chillers - A/C Model RTAA Literature Type G enera l Service Bu l leti n Sequence 4 Date October 1991 File No. SV-RF-RLC -RTAA-SB-4-1091 Supersedes Subject: Sl ide Valve Operation and Troubleshooti ng 0 Introducti on : The purpose of this bulletin is to provide information that is required to troubleshoot the slide valve operator on CHHB compressors . Discussion : The Air Cooled Series R Chiller (RTAA) is designed with 2, 3, or 4 compressors, that include modulating slide valves, that vary the capacity of the compressor. The slide valve is operated by a piston/cylinder assembly. The piston/cylinder assembly is powered by oil pressure that is regulated by two "normally closed" solenoid valves. These valves are called the load and unload solenoid valves (Note: The load solenoid valve is mounted closest to the compressor motor). The coil on each solenoid valve is 110 VAC. Reference Figure 1, to view a schematic of the slide valve hydraulic system. W A C 0 Since the Trane Company has a policy of continuous product improvement, it reserves the right to change specifica- O Ame rican Standard I nc - 1991 tions and design without notice. The installation and servicing of the equipment referred to in this booklet should be done by qua7ified, experienced technicians. Fig ure 1 Typ ical Sli d e Va l ve H ydrau l ic Syste m To Ff 0171 ^ Compressor Oil Suction SuppI Y to U L Unlaading L o a aing Solenoid Vafve So l e n o id V a 1 ve Stide Valve Piston - Slide Valve Shaf t Schroder Valve Piston/Cylinder Assembly Access Sl i de Valve 77-P Load f I* Li_/^^1,11 L ^1 Compressor Rotor The microprocessor controls operate the load and unload solenoid valves, in response to varying demands for capacity. -

Slide Valves: Small Things That Mean a Lot

Royal Belgian Institute of Marine Engineers From the front lines Slide Valves: Small Things That Mean a Lot As with the earlier design, slide valves could be adjusted to favor fuel effi ciency or NOx reduc- tion. In the six years since they were released, the latter attribute has become the object of much investigation. “Using computational fl uid dynamics, we modeled the effect of changing the number of holes, the spray angels and spray patterns,” says Kjeld Aabo, Director of Promotion and Customer Support for MAN B&W. “This reduces the concentration of fuel oil at the injection point, resulting in smaller peak temperatures in the combustion chamber. Changing combustion conditions changes NOx emissions,” he explains. “The benefi t Cross sections of he fuel injector slide valve has been is not related to the slide valve as such, but fuel-valve nozzle Thailed by industry and regulators as to the spray pattern. We then were able to tips. a nice bit of green engineering for develop a kit that could bring our older in- the advances it brought in NOx reduction. service engines up to Tier I standards.” It is a key component in the retrofi t kit that makes 20-year-old engines fi t for IMO “Better fuel effi ciency, more complete Tier I emissions compliance. Interestingly, combustion, less smoke and soot and fewer the slide valve was not invented to reduce engine deposits – for these reasons we imme- NOx, but to improve engine effi ciency and diately deployed slide valves in all engines, cylinder condition. where it was possible to do so,” says Lars- Robert Pedersen, Director of Regulatory Affairs Introduced by MAN B&W in 2002 for its MC for AP Moller-Maersk. -

REEVES Double Cylinder, Simple and Cross Compound Engines

DIRECTIONS FOR OPERATING REEVES Double Cylinder, Simple and Cross Compound Engines Emerson-Brantingham Implement Co., (Incorpo,.,.ted ) Rockford, Illinois REEVES WORKS, COLUMBUS, INDIANA • ~1J,lillII~lIiiOOlm in I J.lililll~~~IIII~lli~ lu l l . I J I I I WlII[)tW:tlJ: I JJJJlmn~~mLIJJ:I]l!lil~t~1il 1 LlI]nlill~il~ru:~I.ld .~.1. 1 1 1 ~Mi~llll[h~m[lm l mm[JIll 'I :J:r,l l , 1 , 1 , Lll .i~ 1.11:ll~m R~ • DIRECTIONS FOR OPERATING Reeves Double Cylinder, Simple and Cross Compound Engines EMERSON-BRANTINGHAM IMPLEMENT COMPANY, ( I ncorporatcd ) ROCKFORD, ILLINOIS REEVES WORKS, COLUMBUS, INDIANA Form A241-5m-5-14 Directions for Operating Reeves Double Cylinder, Simple and Cross Compound Engines The first thing that will be seen when the trimming box is opened is this book, the next thing that shou ld ~e done is to carefully read it. The mar ginal index will help to find the subject on which information is desired. Trimmings The small and deli cate trimmings, also a kit of tools are in the wooden box, other parts are in the smoke box and in the fire box of the boiler. Oil Hol es All the oi l holes, also holes in pipes and in the boi ler are filled with a And Holes wooden plug to keep the ci nders and dust out during transportation. If For Fillings by any means a plug is missing, great care should be taken to clean out the hole before the oil cap or fitting is attached.