United Arab Emirates

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Saudi Arabia.Pdf

A saudi man with his horse Performance of Al Ardha, the Saudi national dance in Riyadh Flickr / Charles Roffey Flickr / Abraham Puthoor SAUDI ARABIA Dec. 2019 Table of Contents Chapter 1 | Geography . 6 Introduction . 6 Geographical Divisions . 7 Asir, the Southern Region � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � �7 Rub al-Khali and the Southern Region � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � �8 Hejaz, the Western Region � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � �8 Nejd, the Central Region � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � �9 The Eastern Region � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � �9 Topographical Divisions . .. 9 Deserts and Mountains � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � �9 Climate . .. 10 Bodies of Water . 11 Red Sea � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � 11 Persian Gulf � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � 11 Wadis � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � 11 Major Cities . 12 Riyadh � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � �12 Jeddah � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � �13 Mecca � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � -

The Foreign Policy of the Arab Gulf Monarchies from 1971 to 1990

The Foreign Policy of the Arab Gulf Monarchies from 1971 to 1990 Submitted by René Rieger to the University of Exeter as a thesis for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Middle East Politics in June 2013 This thesis is available for Library use on the understanding that it is copyright material and that no quotation from the thesis may be published without proper acknowledgement. I certify that all material in this thesis which is not my own work has been identified and that no material has previously been submitted and approved for the award of a degree by this or any other University. Signature: ………… ………… 2 ABSTRACT This dissertation provides a comparative analysis of the foreign policies of the Arab Gulf monarchies during the period of 1971 to 1990, as examined through two case studies: (1) the Arab Gulf monarchies’ relations with Iran and Iraq and (2) the six states’ positions in the Arab-Israeli conflict. The dissertation argues that, in formulating their policies towards Iran and Iraq, the Arab Gulf monarchies aspired to realize four main objectives: external security and territorial integrity; domestic and regime stability; economic prosperity; and the attainment of a stable subregional balance of power without the emergence of Iran or Iraq as Gulf hegemon. Over the largest part of the period under review, the Arab Gulf monarchies managed to offset threats to these basic interests emanating from Iran and Iraq by alternately appeasing and balancing the source of the threat. The analysis reveals that the Arab Gulf monarchies’ individual bilateral relations with Iran and Iraq underwent considerable change over time and, particularly following the Iranian Revolution, displayed significant differences in comparison to one another. -

Bulletin of the Society for Arabian Studies 2009 Number 14 ISSN

Bulletin of the Society for Arabian Studies 2009 Number 14 ISSN: 1361-9144 Registered Charity No. 1003272 2009 £5.00 1 Bulletin of the Society for Arabian Studies 2009 The Society for Arabian Studies President Bulletin of the Society for Arabian Studies Miss Beatrice de Cardi OBE FBA FSA Editor Dr Robert Carter Chairman Ms Sarah Searight Book Reviews Editor Mr William Facey Vice Chairman Dr St John Simpson Treasurer Col Douglas Stobie Honorary Secretary Mrs Ionis Thompson Grants Sub-Committee Prof. Dionisius A. Agius Honorary Secretary Dr St John Simpson Dr Lucy Blue Ms Sarah Searight Dr Harriet Crawford Dr Nelida Fuccaro Dr Nadia Durrani Dr Nadia Durrani Mr William Facey Dr Nelida Fuccaro British Archaeological Mission in Yemen Dr Paul Lunde (BAMY) Dr James Onley Mrs Janet Starkey Chairman Prof. Tony Wilkinson Dr Lloyd Weeks Prof. Tony Wilkinson Notes for contributors to the Bulletin The Bulletin depends on the good will of Society members and correspondents to provide contributions. News, items of general interest, ongoing and details of completed postgraduate research, forthcoming conferences, meetings and special events are welcome. Please contact the Honorary Secretary, Ionis Thompson. Email [email protected] Applications to conduct research in Yemen Applications to conduct research in Yemen should be made to the Society’s sub-committee, the British Archaeological Mission in Yemen (BAMY). Contact Professor Tony Wilkinson, Durham University, Department of Archaeology, South Road, Durham, DH1 3LE. Tel. 0191 334 1111. Email [email protected] Grants in aid of research Applicants are advised to apply well ahead of the May and October deadlines. -

Suddensuccession

SUDDEN SUCCESSION Examining the Impact of Abrupt Change in the Middle East SIMON HENDERSON KRISTIAN C. ULRICHSEN EDITORS MbZ and the Future Leadership of the United Arab Emirates IN PRACTICE, Sheikh Muhammad bin Zayed al-Nahyan, the crown prince of Abu Dhabi, is already the political leader of the United Arab Emirates, even though the federation’s president, and Abu Dhabi’s leader, is his elder half-brother Sheikh Khalifa. This study examines leadership in the UAE and what might happen if, for whatever reason, Sheikh Muham- mad, widely known as MbZ, does not become either the ruler of Abu Dhabi or president of the UAE. THE WASHINGTON INSTITUTE FOR NEAR EAST POLICY ■ POLICY NOTE 65 ■ JULY 2019 SUDDEN SUCCESSION: UAE RAS AL-KHAIMAH UMM AL-QUWAIN AJMAN SHARJAH DUBAI FUJAIRAH ABU DHABI ©1995 Central Intelligence Agency. Used by permission of the University of Texas Libraries, The University of Texas at Austin. Formation of the UAE moniker that persisted until 1853, when Britain and regional sheikhs signed the Treaty of Maritime Peace The UAE was created in November 1971 as a fed- in Perpetuity and subsequent accords that handed eration of six emirates—Abu Dhabi, Dubai, Sharjah, responsibility for conduct of the region’s foreign rela- Fujairah, Ajman, and Umm al-Quwain. A seventh— tions to Britain. When about a century later, in 1968, Ras al-Khaimah—joined in February 1972 (see table Britain withdrew its presence from areas east of the 1). The UAE’s two founding leaders were Sheikh Suez Canal, it initially proposed a confederation that Zayed bin Sultan al-Nahyan (1918–2004), the ruler would include today’s UAE as well as Qatar and of Abu Dhabi, and Sheikh Rashid bin Saeed al-Mak- Bahrain, but these latter two entities opted for com- toum (1912–90), the ruler of Dubai. -

Ruling Families and Business Elites in the Gulf Monarchies: Ever Closer? Ruling Families and Business Elites in the Gulf Monarchies: Ever Closer?

Research Paper Mehran Kamrava, Gerd Nonneman, Anastasia Nosova and Marc Valeri Middle East and North Africa Programme | November 2016 Ruling Families and Business Elites in the Gulf Monarchies: Ever Closer? Ruling Families and Business Elites in the Gulf Monarchies: Ever Closer? Summary • The pre-eminent role of nationalized oil and gas resources in the six Gulf monarchies has resulted in a private sector that is highly dependent on the state. This has crucial implications for economic and political reform prospects. • All the ruling families – from a variety of starting points – have themselves moved much more extensively into business activities over the past two decades. • Meanwhile, the traditional business elites’ socio-political autonomy from the ruling families (and thus the state) has diminished throughout the Gulf region – albeit again from different starting points and to different degrees today. • The business elites’ priority interest in securing and preserving benefits from the rentier state has led them to reinforce their role of supporter of the incumbent regimes and ruling families. In essence, to the extent that business elites in the Gulf engage in policy debate, it tends to be to protect their own privileges. This has been particularly evident since the 2011 Arab uprisings. • The overwhelming dependence of these business elites on the state for revenues and contracts, and the state’s key role in the economy – through ruling family members’ personal involvement in business as well as the state’s dominant ownership of stocks in listed companies – means that the distinction between business and political elites in the Gulf monarchies has become increasingly blurred. -

Burj Al Arab: the Only 7-Star Hotel in the World

TRAVEL Burj Al Arab: The only 7-Star Hotel in the World by Engr. Chin Mee Poon, FIEM, P. Eng. ON our way back from Scotland, my wife and I stopped over at Dubai for three nights to see how much the place has progressed since our last visit in 2002. Dubai is a tiny emirate situated near the tip of a promontory of the Arabic Peninsula that separates the Persian Gulf from the Gulf of Oman. It is the second largest of the seven emirates that make up the United Arab Emirates, one of the richest Arabic countries. Before oil was discovered in the 1960s, Dubai was poor and its people lived a nomadic life in a desert environment. In less than half a century, the desert land on both sides of Another first is, of course, the well-known Burj Al Arab, the Dubai Creek has been transformed into a large oasis of often touted as the world’s only 7-star hotel. Built on an concrete jungle, and this oasis is still expanding with more artificial island in the vicinity of the luxurious 5-star Jumeirah giant structures shooting up to scrap the sky. Beach Hotel, this all-suite hotel is in the shape of a sail. It is estimated that 20% of the world’s tower cranes are At 321m, it is also the tallest hotel in the world. And with currently employed in Dubai. Of its population of about its cheapest suite going for about Dh3,500 (about RM3,500) a 1.5 million people, almost 80% are foreign workers from night, it is definitely the most expensive hotel in the world. -

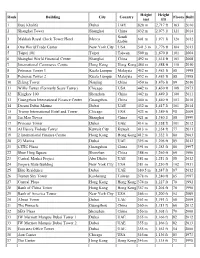

List of World's Tallest Buildings in the World

Height Height Rank Building City Country Floors Built (m) (ft) 1 Burj Khalifa Dubai UAE 828 m 2,717 ft 163 2010 2 Shanghai Tower Shanghai China 632 m 2,073 ft 121 2014 Saudi 3 Makkah Royal Clock Tower Hotel Mecca 601 m 1,971 ft 120 2012 Arabia 4 One World Trade Center New York City USA 541.3 m 1,776 ft 104 2013 5 Taipei 101 Taipei Taiwan 509 m 1,670 ft 101 2004 6 Shanghai World Financial Center Shanghai China 492 m 1,614 ft 101 2008 7 International Commerce Centre Hong Kong Hong Kong 484 m 1,588 ft 118 2010 8 Petronas Tower 1 Kuala Lumpur Malaysia 452 m 1,483 ft 88 1998 8 Petronas Tower 2 Kuala Lumpur Malaysia 452 m 1,483 ft 88 1998 10 Zifeng Tower Nanjing China 450 m 1,476 ft 89 2010 11 Willis Tower (Formerly Sears Tower) Chicago USA 442 m 1,450 ft 108 1973 12 Kingkey 100 Shenzhen China 442 m 1,449 ft 100 2011 13 Guangzhou International Finance Center Guangzhou China 440 m 1,440 ft 103 2010 14 Dream Dubai Marina Dubai UAE 432 m 1,417 ft 101 2014 15 Trump International Hotel and Tower Chicago USA 423 m 1,389 ft 98 2009 16 Jin Mao Tower Shanghai China 421 m 1,380 ft 88 1999 17 Princess Tower Dubai UAE 414 m 1,358 ft 101 2012 18 Al Hamra Firdous Tower Kuwait City Kuwait 413 m 1,354 ft 77 2011 19 2 International Finance Centre Hong Kong Hong Kong 412 m 1,352 ft 88 2003 20 23 Marina Dubai UAE 395 m 1,296 ft 89 2012 21 CITIC Plaza Guangzhou China 391 m 1,283 ft 80 1997 22 Shun Hing Square Shenzhen China 384 m 1,260 ft 69 1996 23 Central Market Project Abu Dhabi UAE 381 m 1,251 ft 88 2012 24 Empire State Building New York City USA 381 m 1,250 -

Burj Khalifa Tower

Burj Khalifa Tower The tallest structure in the world, standing at 2,722 ft (830 meters), just over 1/2 mile high, Burj Khalifa (Khalifa Tower) opened in 2010 as a centerpiece building in a large-scale, mixed-use development called Downtown Dubai. The building originally referred to as Dubai Tower was renamed in honor of the president of the United Arab Emirates, Khalifa bin Zayed Al Nahyan. Burj Khalifa Dubai, United Arab Emirates Architecture Style Modern Skyscraper | Neo-Futurism Glass, Steel, Aluminum & Reinforced Concrete Prominent Architecture Features Y-Shaped Floor Plan Maximizes Window Perimeter Areas for residential and hotel space Buttressed central core and wing design to support the height of the building 27 setbacks in a spiraling pattern Main Structure 430,000 cubic yards reinforced concrete and 61,000 tons rebar Foundation - 59,000 cubic yards concrete and 192 piles 164 ft (50 m) deep Highly compartmentalized, pressurized refuge floors for life safety Facade Aluminum and textured stainless steel spandrel panels with low-E glass Vertical polished stainless steel fins Observation Deck - 148th Floor PROJECT SUMMARY Project Description Burj Kahlifa, the tallest building in the world, has redefined the possibilities in the design, engineering, and construction of mega-tall buildings. Incorporating periodic setbacks at the ends of each wing, the tower tapers in an upward spiraling pattern that decreases is mass as the height of the tower increases. The building’s design included multiple wind tunnel tests and design adjustments to develop optimum performance relative to wind and natural forces. The building serves as a model for the concept of future, compact, livable, urban centers with direct connections to mass transit systems. -

The World's 500 Most Influential Muslims, 2021

PERSONS • OF THE YEAR • The Muslim500 THE WORLD’S 500 MOST INFLUENTIAL MUSLIMS • 2021 • B The Muslim500 THE WORLD’S 500 MOST INFLUENTIAL MUSLIMS • 2021 • i The Muslim 500: The World’s 500 Most Influential Chief Editor: Prof S Abdallah Schleifer Muslims, 2021 Editor: Dr Tarek Elgawhary ISBN: print: 978-9957-635-57-2 Managing Editor: Mr Aftab Ahmed e-book: 978-9957-635-56-5 Editorial Board: Dr Minwer Al-Meheid, Mr Moustafa Jordan National Library Elqabbany, and Ms Zeinab Asfour Deposit No: 2020/10/4503 Researchers: Lamya Al-Khraisha, Moustafa Elqabbany, © 2020 The Royal Islamic Strategic Studies Centre Zeinab Asfour, Noora Chahine, and M AbdulJaleal Nasreddin 20 Sa’ed Bino Road, Dabuq PO BOX 950361 Typeset by: Haji M AbdulJaleal Nasreddin Amman 11195, JORDAN www.rissc.jo All rights reserved. No part of this book may be repro- duced or utilised in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanic, including photocopying or recording or by any information storage and retrieval system, without the prior written permission of the publisher. Views expressed in The Muslim 500 do not necessarily reflect those of RISSC or its advisory board. Set in Garamond Premiere Pro Printed in The Hashemite Kingdom of Jordan Calligraphy used throughout the book provided courte- sy of www.FreeIslamicCalligraphy.com Title page Bismilla by Mothana Al-Obaydi MABDA • Contents • INTRODUCTION 1 Persons of the Year - 2021 5 A Selected Surveyof the Muslim World 7 COVID-19 Special Report: Covid-19 Comparing International Policy Effectiveness 25 THE HOUSE OF ISLAM 49 THE -

Reflecting on the Inauguration of the Burj Khalifa, Dubai 2010

ctbuh.org/papers Title: Reflecting on the Inauguration of the Burj Khalifa, Dubai 2010 Author: Pierre Marcout, President & Artistic Director, Prisme Entertainment Subjects: Building Case Study History, Theory & Criticism Keywords: Community Height Megatall Publication Date: 2015 Original Publication: The Middle East: A Selection of Written Works on Iconic Towers and Global Place-Making Paper Type: 1. Book chapter/Part chapter 2. Journal paper 3. Conference proceeding 4. Unpublished conference paper 5. Magazine article 6. Unpublished © Council on Tall Buildings and Urban Habitat / Pierre Marcout Reflecting on the Inauguration of the Burj Khalifa, Dubai 2010 Pierre Marcout, President & Artistic Director, Prisme Entertainment Inc. & Prisme International Dubai is a city that emerged in only a decade. be intrigued to discover the real amazing story Later in life, my first job was to manage Though facing successive challenges it has behind presenting this new global icon. a branch for an important distributor built an attractive reputation around the of electric materials. Of course, my own world. Criticized and envied, it multiplies the interests in lighting led me to develop a new superlatives and keeps being talked about. Its I was always fascinated by light. In the market segment that exposed new designs and presentations for lighting. I jumped notoriety is impressive compared to its relative beginning, I was drawn to the colored lights in my bedroom, but my goal was not to on this success to learn more about the size. Dubai holds in its name a fantastic power create a night club, because at 10 years of capacity to create different atmospheres in of attraction, and Burj Khalifa (828m, 162 floors) age, my parents would have never allowed offices and homes through lighting alone, became the emblem of the new century upon that to happen. -

RJSSER ISSN 2707-9015 (ISSN-L) Research Journal of Social DOI: Sciences & Economics Review ______

Research Journal of Social Sciences & Economics Review Vol. 1, Issue 4, 2020 (October – December) ISSN 2707-9023 (online), ISSN 2707-9015 (Print) RJSSER ISSN 2707-9015 (ISSN-L) Research Journal of Social DOI: https://doi.org/10.36902/rjsser-vol1-iss4-2020(225-232) Sciences & Economics Review ____________________________________________________________________________________ Urdubic as a Lingua Franca in the Arab Countries of the Persian Gulf * Dr. Riaz Hussain, Head ** Dr. Muhamad Asif, Head *** Dr. Muhammad Din __________________________________________________________________________________ Abstract A new lingua franca, Urdubic, is emerging in the Arab countries of the Persian Gulf. Its linguistic composition is defined by the reduced and simplified forms of Arabic and Urdu. The paper examines linguistic, social, and historical aspects of its sociolinguistic make-up. Recurrent patterns of mutual migration between Arabs and Indians have played a pivotal role in the development of this lingua franca. Today, it appears to permeate the very homes of the Arabs. The examples of linguistic features (combinations of Urdu and Arabic) of the pidgin mentioned in the current study show that Urban Arabic is accepting foreign influences. This influx of foreign languages has alarmed those Arabs who want to preserve the purity of Arabic. How long Urdubic is going to survive amid Arabs’ efforts to save Arabic from such foreign influences? The paper concludes with speculations about the future of Urdubic. Keywords: Pidgins, creoles, Persian Gulf, Arabic, Urdu Introduction Change is an integral part of life. There are changes in human society that are noticed at the time of occurrences such as economic reforms and sudden political changes. But, there are finer changes regarding human linguistic behavior that may occur as a result of large-scale social, economic, and political changes and may be noticed only after years of latent development. -

Oman and Japan

Oman and Japan Unknown Cultural Exchange between the two countries Haruo Endo Oman and Japan and Endo Oman Haruo Haruo Endo This book is basically a translation of the Japanese edition of “Oman Kenbunroku; Unknown cultural exchange between the two countries” Publisher: Haruo Endo Cover design: Mr Toshikazu Tamiya, D2 Design House © Prof. Haruo Endo/Muscat Printing Press, Muscat, Oman 2012 All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in or introduced into a retrieval system or transmitted, in any form or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise) without the written permission of the copyright owners. Oman and Japan Unknown Cultural Exchange between the two countries Haruo Endo Haruo Endo (b.1933), Oman Expert, author of “Oman Today” , “The Arabian Peninsula” , “Records of Oman” and Japanese translator of “A Reformer on the Throne- Sultan Qaboos bin Said Al Said”. Awarded the Order of HM Sultan Qaboos for Culture, Science and Art (1st Class) in 2007. Preface In 2004, I was requested to give a lecture in Muscat to commemorate the 30th anniversary of the establishment of the Oman-Japan Friendship Association, sponsored jointly by the Oman-Japan Friendship Association, Muscat Municipality, the Historical Association of Oman and the Embassy of Japan. It was an unexpected honour for me to be given such an opportunity. The subject of the lecture was “History of Exchange between Japan and Oman”. After I had started on my preparation, I learned that there was no significant literature on this subject. I searched for materials from scratch. I then organized the materials relating to the history of human exchange, the development of trade since the Meiji period (1868-1912) and the cultural exchanges between both countries.