Animal Cruelty Prosecution

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

"Cruelty Takes the Place of Love": a Magic Lantern Slide and the Band of Hope by Stephanie Olsen

"Cruelty takes the place of love": A Magic Lantern Slide and the Band of Hope by Stephanie Olsen Ephemera can be real treasure, especially perhaps for the historian of emotions. It can allow us to conceive of the emotive qualities of actors or events in different ways from sources that were meant to be preserved for posterity. This piece of ephemera, fortuitously preserved long after its technology was made obsolete, is a magic lantern slide. The magic lantern was widely used, in an era before the spread of movies and computers, for entertainment, sometimes combined with education. The medium was ubiquitous in the © The Livesey Collection, University of Central Lancashire, Preston, UK Victorian and Edwardian eras, yet, because of the equipment required, rare enough to be special to viewers. The British Band of Hope movement used this medium widely, and its major unions under which local bands were active had well- organized lending policies of magic lantern slides and projectors. But what can one dusty slide tell us about the motivations of the adults or the children involved in this movement, and how can it enlighten us as historians of emotion? My research explores important historical attempts to cultivate the "right" emotions in boys, to promote manliness, future fatherhood and citizenship.[1] The Band of Hope is an important part of this story. An influential multi-denominational, mainly working-class national temperance movement in Britain, it attracted over three-million boys and girls at its peak, around 1914.[2] According to Charles Wakely, the General Secretary of the United Kingdom Band of Hope Union, the age of membership differed in various societies, but in most Bands of Hope the members were received at seven years of age, and at fourteen were drafted into a senior society, where the proceedings were adapted to their "increased intelligence and altered habits of thought".[3] Membership was conditional upon giving a written promise of abstinence, and upon compliance with the rules that governed each society. -

The Recognition of Passion in Selected Fiction of E. M. Forster

THE RECOGNITION OF PASSION IN SELECTED FICTION OF E. M. FORSTER by Joyce Nichols Submitted as an Honors Paper in the Department of English The University of North Carolina at Greensboro 1964 Approved by JV Vtr \ VVfl, i •*) r\ Director Examining Committee 1/0,-HSI ^V AdJ^y- A K-t'-fZr^.-T^ft—* ■** —/««g>*. One does not read E. M. Forster without becoming aware very quickly that Mr. Forster is probably England's most articulate and convincing champion of the passionate life. Passion to Mr. Forster has many faces; indeed it is a whole way of life. It is the purpose of this paper to define the many different aspects of this Forsterian passion and to observe its development or denial in several characters of his selected fiction. It is difficult, as I write about E. M. Forster, to believe that he is in his eighty-sixth year and that he has not published a novel in forty years. It is difficult to accept these biological and literary facts because, even today, p?r,s° works retain a freshness and vitality that many later works of English fiction lack. What then gives these qualities to his fiction, some of which was written more than 40 years ago? Partly, it is because Mr. F«riis concerned with universal themes but it is also because he has managed to communicate some of the wonder and idealism of the child in a jaded century. He invites us to climb through to the other side of the hedge1 and begin to live. He is essentially didactic in his writings but his didactism is gentle and becomes less insistent, more subtle and tentative by the time of A Passage to India. -

Definitions of Child Abuse and Neglect

STATE STATUTES Current Through March 2019 WHAT’S INSIDE Defining child abuse or Definitions of Child neglect in State law Abuse and Neglect Standards for reporting Child abuse and neglect are defined by Federal Persons responsible for the child and State laws. At the State level, child abuse and neglect may be defined in both civil and criminal Exceptions statutes. This publication presents civil definitions that determine the grounds for intervention by Summaries of State laws State child protective agencies.1 At the Federal level, the Child Abuse Prevention and Treatment To find statute information for a Act (CAPTA) has defined child abuse and neglect particular State, as "any recent act or failure to act on the part go to of a parent or caregiver that results in death, https://www.childwelfare. serious physical or emotional harm, sexual abuse, gov/topics/systemwide/ or exploitation, or an act or failure to act that laws-policies/state/. presents an imminent risk of serious harm."2 1 States also may define child abuse and neglect in criminal statutes. These definitions provide the grounds for the arrest and prosecution of the offenders. 2 CAPTA Reauthorization Act of 2010 (P.L. 111-320), 42 U.S.C. § 5101, Note (§ 3). Children’s Bureau/ACYF/ACF/HHS 800.394.3366 | Email: [email protected] | https://www.childwelfare.gov Definitions of Child Abuse and Neglect https://www.childwelfare.gov CAPTA defines sexual abuse as follows: and neglect in statute.5 States recognize the different types of abuse in their definitions, including physical abuse, The employment, use, persuasion, inducement, neglect, sexual abuse, and emotional abuse. -

Examining the Effect of Childhood Animal Cruelty Motives on Recurrent Adult Violent Crimes Toward Humans

EXAMINING THE EFFECT OF CHILDHOOD ANIMAL CRUELTY MOTIVES ON RECURRENT ADULT VIOLENT CRIMES TOWARD HUMANS By Joshua C. Overton Approved: __________________________________ _________________________________ Christopher Hensley Tammy Garland Associate Professor of Criminal Justice Assistant Professor of Criminal Justice (Director of Thesis) (Committee Member) __________________________________ _________________________________ Karen McGuffee Herbert Burhenn Associate Professor of Legal Dean of the College of Assistant Studies Arts and Sciences (Committee Member) __________________________________ Gerald Ainsworth Dean of the Graduate School Examining the Effect of Childhood Animal Cruelty Motives on Recurrent Adult Violent Crimes Toward Humans A Thesis Presented for the Masters of Science Degree The University of Tennessee, Chattanooga Joshua C. Overton August 2011 Copyright © 2011 by Joshua C. Overton All rights reserved ii DEDICATION To my wife Sharon Overton Grandfather Raymond Maurice Burdette Mother Brenda Overton Father Gary Overton iii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I would like to express my deepest gratitude to Dr. Christopher Hensley for his support and willingness to assist in my thesis preparation. Dr. Hensley constantly encouraged me to pursue a graduate degree and was extremely helpful throughout my tenure in Criminal Justice. It was with his guidance that I was able to complete the thesis process. Additionally, I would like to thank Dr. Vic Bumphus for continually encouraging me to pursue a higher education degree and for his constant support and advice throughout my time in the Criminal Justice Department. I would also like to thank Dr. Tammy Garland and Professor Karen McGuffee for serving on my thesis committee. They were both extremely supportive and helpful during my time pursuing a graduate degree. Finally, I would like to thank the entire Criminal Justice Department at UTC for educating me at the highest level and making my time in Criminal Justice extremely enjoyable. -

The Behavioural Manifestations of Animal Cruelty / Abuse

The behavioural manifestations of animal cruelty / abuse Dr Kersti Seksel BVSc (Hons) MRCVS MA (Hons) FACVSc (Animal Behaviour) Dipl ACVB Registered Veterinary Specialist in Animal behaviour Sydney Animal Behaviour Service, 55 Ethel Street, Seaforth, NSW 2092. [email protected] www.sabs.com.au Abstract There has been a close association between humans and animals for thousands of years with dogs being kept as pets for over 15,000 years. Research has shown that although most of the relationships between animals and humans provide some benefits to both parties there have always been recognised problems. The subject of animal abuse / animal cruelty is now increasingly being documented and studied. Some of this abuse may be accidental, even inadvertent, due to misunderstanding or ignorance of animals and their behaviour. However, not all abuse is accidental. Increasingly a correlation between animal abuse, domestic violence and child abuse has been recognised. To date most of the papers have examined the physical manifestations of animal abuse that have been identified with the main emphasis in companion animals (commonly dogs and cats). This introductory paper will cover some of the potential behavioural manifestations that veterinarians should be aware of when confronted by a companion dog or cat that may have been abused. It will also discuss the important role veterinarians have in not only recognising animal abuse but also in prevention. What is abuse? To abuse is defined as maltreatment: the physical or psychological maltreatment of a person or animal; or harmful practice: to use wrongly or improperly, to misuse. Synonyms include mistreat, injure, and damage 1. -

ASPCA®Mission:Orange

ActionSpring 2007 ASPCA®Mission: Orange™ The ASPCA reaches out to communities nationwide to build a more humane future coast to coast >> PRESIDENT’S NOTE If there were ever any doubt that Americans love their pets, the facts Board of Directors speak for themselves. A recent Officers of the Board American Pet Products Hoyle C. Jones, Chairman, Linda Lloyd Lambert, Manufacturers Association National Vice Chairman, Sally Spooner, Secretary, Pet Owners’ Survey found that James W. Gerard, Treasurer 63% of U.S. households have a pet, Members of the Board Photo by Kristy Leibowitz which equates to 69.1 million Penelope Ayers, Alexandra G. Bishop, J. Elizabeth homes. Of these, 43 million homes have more than one Bradham, Reenie Brown, Patricia J. Crawford, pet. But sadly, for every pet that finds a caring home, Jonathan D. Farkas, Joan C. Hendricks, V.M.D., Ph.D., millions of other animals’ life stories end prematurely in Franklin Maisano, Elizabeth L. Mathieu, Esq., shelters across America. William Morrison Matthews, Majella Matyas, As we enter our 141st year, it gives me great pleasure to Sean McCarthy, Gurdon H. Metz, Leslie Anne Miller, Michael F.X. Murdoch, James L. Nederlander, Jr., let you know that the ASPCA is doing more than ever to Marsha Reines Perelman, George Stuart Perry, help build a more humane future for America’s animals. Helen S.C. Pilkington, Gail Sanger, William Secord, The ASPCA is proud to partner with target animal Frederick Tanne, Richard C. Thompson, welfare organizations across the country to launch Cathy Wallach “ASPCA® Mission: Orange™”—a focused effort to create Directors Emeriti a country of humane communities, one community at a Steven M. -

Investigating & Prosecuting Animal Abuse

Photo credits: Animal photos compliments of Four Foot Photography (except dog and cat on back cover and goat); photo of Allie Phillips by Michael Carpenter and photo of Randall Lockwood from ASPCA. All rights reserved. National District Attorneys Association National Center for Prosecution of Animal Abuse 99 Canal Center Plaza, Suite 330 Alexandria,VA 22314 www.ndaa.org Scott Burns Executive Director Allie Phillips Director, National Center for Prosecution of Animal Abuse Deputy Director, National Center for Prosecution of Child Abuse © 2013 by the National District Attorneys Association. This project was supported by a grant from the Animal Welfare Trust. This information is offered for educational purposes only and is not legal advice. Points of view or opinions in this publication are those of the authors and do not represent the official position or policies of the National District Attorneys Association or the Animal Welfare Trust. Investigating & Prosecuting Animal Abuse ABOUT THE AUTHORS Allie Phillips is a former prosecuting attorney and author who is nationally recognized for her work on behalf of animals. She is the Director of the National Center for Prosecution of Animal Abuse and Deputy Director of the National Center for Prosecution of Child Abuse at the National District Attorneys Association. She was an Assistant Prosecuting Attorney in Michigan and subsequently the Vice President of Public Policy and Human-Animal Strategic Initiatives for American Humane Association. She has been training criminal justice profes- sionals since 1997 and has dedicated her career to helping our most vulnerable victims. She specializes in the co-occurrence between violence to animals and people and animal protec- tion, and is the founder of Sheltering Animals & Families Together (SAF-T) Program, the first and only global initiative working with domestic violence shelters to welcome families with pets. -

Themes List (Quotations, Mottos, Proverbs and Old Sayings)

Themes List (Quotations, Mottos, Proverbs and Old Sayings) Prejudice • Things are not always as they appear. • Things are usually not as bad as you think they will be. • Look for the golden lining. • Beauty is only skin deep. • Prejudice leads to: wrong conclusions, violence, false perceptions, a vicious cycle, oppression. o Don’t judge a book by its cover. o Mercy triumphs over judgment. • Beware of strangers. • People from other cultures are really very much like us. • Look before you leap. Belief • Believe in yourself. To succeed, we must first believe that we can. • Believe one who has proved it. Believe an expert. • The thing always happens that you really believe in; and the belief in a thing makes it happen. • One needs something to believe in, something for which one can have whole-hearted enthusiasm. • As long as people believe in absurdities, they will continue to commit atrocities. • Moral skepticism can result in distance, coldness, and cruelty. Change • People are afraid of change but things always change. • Things are usually not as bad as you think they will be. • Knowledge can help us prepare for the future. • Forewarned is forearmed. • It is impossible to be certain about things. Good and Evil • Good triumphs over evil. • Evil is punished and good is rewarded. • Power corrupts and absolute power corrupts absolutely. • Bullies can be overcome. • Good manners have positive results. • Greed leads to negative outcomes: suffering, disaster, catastrophe, evil, callousness, arrogance, megalomania. • It is possible to survive against all odds. • Jealousy leads to negative outcomes: guilt, resentment, loneliness, violence, madness. • Good and evil coexist. -

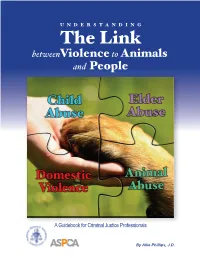

Understanding the Link Between Violence to Animals and People: a Guidebook for Criminal Justice Professionals

UNDERSTANDING The Link between Violence to Animals and People A Guidebook for Criminal Justice Professionals By Allie Phillips, J.D. National District Attorneys Association 99 Canal Center Plaza, Suite 330 Alexandria, VA 22314 www.ndaa.org Kay Chopard Cohen Executive Director Allie Phillips Director, National Center for Prosecution of Animal Abuse Deputy Director, National Center for Prosecution of Child Abuse June 2014 © 2014 by the National District Attorneys Association. This project was supported by a grant from the American Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals (ASPCA) and Grant No. 2012-CI-FX-K007 awarded by the Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention, Office of Justice Programs, U.S. Department of Justice. Points of view or opinions in this document are those of the author and do not necessarily represent the official position or policies of the U.S. Department of Justice. This information is offered for educational purposes only and is not to be considered legal advice. UNDERSTANDING The Link between Violence to Animals and People A Guidebook for Criminal Justice Professionals By Allie Phillips, J.D. Understanding the Link between Violence to Animals and People: A Guidebook for Criminal Justice Professionals ABOUT THE AUTHOR Allie Phillips is a former prosecuting attorney, animal advocate, and published author who is nationally recognized for her work on behalf of animals and vulnerable vic- tims. She is the Director of the National Center for Prosecution of Animal Abuse and Deputy Director of the National Center for Prosecution of Child Abuse at the Na- tional District Attorneys Association in Alexandria, Virginia. -

Winter 2002 Volume 21 INSIDE: New York to Mutts: “You’Re Worthless” See Page 3

Winter 2002 Volume 21 INSIDE: New York to Mutts: “You’re Worthless” See Page 3 THE QUARTERLY NEWSLETTER OF THE ANIMAL LEGAL DEFENSE FUND Darwin, Meet Dershowitz Courting legal evolution at Harvard Law ights,” declared Alan Dershowitz, pacing the floor of a lecture hall at Harvard Law School, “grow out of wrongs.” “ It seemed the type of pronounce- Rment Dershowitz, who teaches law at Harvard, might deliver during a typical lecture to one of his classes. But this was no typical lecture, and the Ames Courtroom in Austin Hall bore only a passing resemblance to The Paper Chase. The scene was a first-of-its-kind symposium, “The Evolving Legal Status of Chimpanzees.” And Dershowitz’s featured role signaled how far the idea of legal rights for animals has come since the PHOTO BY NANCY O’BRIEN 1970s, when the fictional Professor Kingsfield did his blustery best to stem the tide of change at Harvard and beyond. Harvard Law School today boasts one of the most active chapters of the Student Animal Legal Defense Fund in the nation. The chapter co-spon- sored the daylong symposium with the Chim- panzee Collaboratory, a consortium of attorneys, scientists and public-policy experts of which sionate to those on whom we impose our rules. Still a “legal thing”— ALDF is a charter member. The symposium was Hence the argument for animal rights.” but for how long? moderated by ALDF President Steve Ann Cham- With his fellow legal scholars Laurence Tribe bers, chair of the Collaboratory’s legal committee (who was scheduled to speak at the symposium, and the primary organizer of the event. -

Annotated Bibliography: Cruelty to Animals and Violence to Humans (1998-2013)

WellBeing International WBI Studies Repository 9-17-2014 Annotated Bibliography: Cruelty to Animals and Violence to Humans (1998-2013) Erich Yahner Humane Society Institute for Science and Policy Follow this and additional works at: https://www.wellbeingintlstudiesrepository.org/hum_ed_bibs Recommended Citation Yahner, Erich, "Annotated Bibliography: Cruelty to Animals and Violence to Humans (1998-2013)" (2014). BIBLIOGRAPHIES. 5. https://www.wellbeingintlstudiesrepository.org/hum_ed_bibs/5 This material is brought to you for free and open access by WellBeing International. It has been accepted for inclusion by an authorized administrator of the WBI Studies Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. An Annotated Bibliography of Research Relevant to Cruelty to Animals and Violence to Humans 1998-2013 The Humane Society Institute for Science and Policy Compiled by Erich Yahner (All Abstracts and Summaries from Authors or Publishers) JOURNAL ARTICLES Ascione, F.R., & Shapiro, K. (2009). People and animals, kindness and cruelty: Research directions and policy implications. Journal of Social Issues,65(3), 569-587. This article addresses the challenges of defining and assessing animal abuse, the relation between animal abuse and childhood mental health, the extensive research on animal abuse and intimate partner violence, and the implication of these empirical findings for programs to enhance human and animal welfare. Highlighted are recent developments and advances in research and policy issues on animal abuse. The reader is directed to existing reviews of research and areas of focus on the expanding horizon of empirical analyses and programmatic innovations addressing animal abuse. Following a discussion of forensic and veterinary issues related to animal abuse, we discuss policy issues including how the status of animals as human companions at times may place animals at risk. -

Negative Emotional Energy: a Theory of the “Dark-Side” of Interaction Ritual Chains

Soc. Sci. 2015, 4, 148–170; doi:10.3390/socsci4010148 OPEN ACCESS social sciences ISSN 2076-0760 www.mdpi.com/journal/socsci Article Negative Emotional Energy: A Theory of the “Dark-Side” of Interaction Ritual Chains David Boyns * and Sarah Luery Department of Sociology, California State University, Northridge, 18111 Nordhoff Street, Northridge, CA 91330-8318, USA; E-Mail: [email protected] * Author to whom correspondence should be addressed; E-Mail: [email protected]; Tel.: +1-818-677-6803. Academic Editor: Martin J. Bull Received: 22 December 2014 / Accepted: 2 February 2015 / Published: 10 February 2015 Abstract: Randall Collins’ theory of interaction ritual chains is widely cited, but has been subject to little theoretical elaboration. One reason for the modest expansion of the theory is the underdevelopment of the concept of emotional energy. This paper examines emotional energy, related particularly to the dynamics of negative experiences. It asks whether or not negative emotions produce emotional energies that are qualitatively distinct from their positive counterparts. The analysis begins by tracing the development of Interaction Ritual Theory, and summarizes its core propositions. Next, it moves to a conceptualization of a “valenced” emotional energy and describes both “positive” and “negative” dimensions. Six propositions outline the central dynamics of negative emotional energy. The role of groups in the formation of positive and negative emotional energy are considered, as well as how these energies are significant sources of sociological motivation. Keywords: sociological theory; sociology of emotions; rituals; social interaction; group dynamics 1. Introduction One of the sociological theories developed in recent decades is Randall Collins’ Interaction Ritual Theory (IRT).