Passion Work: the Joint Production of Emotional Labor Tyson Smith

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Effects of Workplace Loneliness on Work Engagement and Organizational Commitment: Moderating Roles of Leader-Member Exchange and Coworker Exchange

sustainability Article The Effects of Workplace Loneliness on Work Engagement and Organizational Commitment: Moderating Roles of Leader-Member Exchange and Coworker Exchange Hyo Sun Jung 1 , Min Kyung Song 2 and Hye Hyun Yoon 2,* 1 Center for Converging Humanities Kyung Hee University, Seoul 02447, Korea; [email protected] 2 Department of Culinary Arts and Food Service Management, Kyung Hee University, Seoul 02447, Korea; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected] Abstract: This study aims to examine the effect of workplace loneliness on work engagement and organizational commitment and the moderating role of social relationships between an employee and his or her superior and coworkers in such mechanisms. Workplace loneliness decreased employees’ engagement with their jobs and, as such, decreased engagement had a positive relationship with organizational commitment. Also, the negative influence of workplace loneliness on work engage- ment was found to be moderated by coworker exchange, and employees’ maintenance of positive social exchange relationships with their coworkers was verified to be a major factor for relieving the negative influence of workplace loneliness. Keywords: workplace loneliness; work engagement; organizational commitment; leader-member exchange; coworker exchange; deluxe hotel Citation: Jung, H.S.; Song, M.K.; Yoon, H.H. The Effects of Workplace 1. Introduction Loneliness on Work Engagement and Organizational Commitment: Workplace loneliness does harm to an organization as well as its employees [1]. In an Moderating Roles of Leader-Member organization, employees perform their jobs amid diverse and complex interpersonal rela- Exchange and Coworker Exchange. tionships, and if they fail to bear such relationships in a basic social dimension, they will be Sustainability 2021, 13, 948. -

The Role of Exporters' Emotional Intelligence in Building Foreign

This is a repository copy of The Role of Exporters’ Emotional Intelligence in Building Foreign Customer Relationships. White Rose Research Online URL for this paper: http://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/150142/ Version: Accepted Version Article: Leonidou, LC, Aykol, B, Fotiadis, TA et al. (2 more authors) (2019) The Role of Exporters’ Emotional Intelligence in Building Foreign Customer Relationships. Journal of International Marketing, 27 (4). pp. 58-80. ISSN 1069-031X https://doi.org/10.1177/1069031X19876642 © American Marketing Association, 2019. This is an author produced version of an article published in the Journal of International Marketing. Uploaded in accordance with the publisher's self-archiving policy. Reuse Items deposited in White Rose Research Online are protected by copyright, with all rights reserved unless indicated otherwise. They may be downloaded and/or printed for private study, or other acts as permitted by national copyright laws. The publisher or other rights holders may allow further reproduction and re-use of the full text version. This is indicated by the licence information on the White Rose Research Online record for the item. Takedown If you consider content in White Rose Research Online to be in breach of UK law, please notify us by emailing [email protected] including the URL of the record and the reason for the withdrawal request. [email protected] https://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/ The Role of Exporters’ Emotional Intelligence in Building Foreign Customer Relationships Abstract Despite the critical importance of emotional intelligence in effectively interacting with other people, its role has been overlooked in scholarly research on cross-border interorganizational relationships. -

"Cruelty Takes the Place of Love": a Magic Lantern Slide and the Band of Hope by Stephanie Olsen

"Cruelty takes the place of love": A Magic Lantern Slide and the Band of Hope by Stephanie Olsen Ephemera can be real treasure, especially perhaps for the historian of emotions. It can allow us to conceive of the emotive qualities of actors or events in different ways from sources that were meant to be preserved for posterity. This piece of ephemera, fortuitously preserved long after its technology was made obsolete, is a magic lantern slide. The magic lantern was widely used, in an era before the spread of movies and computers, for entertainment, sometimes combined with education. The medium was ubiquitous in the © The Livesey Collection, University of Central Lancashire, Preston, UK Victorian and Edwardian eras, yet, because of the equipment required, rare enough to be special to viewers. The British Band of Hope movement used this medium widely, and its major unions under which local bands were active had well- organized lending policies of magic lantern slides and projectors. But what can one dusty slide tell us about the motivations of the adults or the children involved in this movement, and how can it enlighten us as historians of emotion? My research explores important historical attempts to cultivate the "right" emotions in boys, to promote manliness, future fatherhood and citizenship.[1] The Band of Hope is an important part of this story. An influential multi-denominational, mainly working-class national temperance movement in Britain, it attracted over three-million boys and girls at its peak, around 1914.[2] According to Charles Wakely, the General Secretary of the United Kingdom Band of Hope Union, the age of membership differed in various societies, but in most Bands of Hope the members were received at seven years of age, and at fourteen were drafted into a senior society, where the proceedings were adapted to their "increased intelligence and altered habits of thought".[3] Membership was conditional upon giving a written promise of abstinence, and upon compliance with the rules that governed each society. -

The Recognition of Passion in Selected Fiction of E. M. Forster

THE RECOGNITION OF PASSION IN SELECTED FICTION OF E. M. FORSTER by Joyce Nichols Submitted as an Honors Paper in the Department of English The University of North Carolina at Greensboro 1964 Approved by JV Vtr \ VVfl, i •*) r\ Director Examining Committee 1/0,-HSI ^V AdJ^y- A K-t'-fZr^.-T^ft—* ■** —/««g>*. One does not read E. M. Forster without becoming aware very quickly that Mr. Forster is probably England's most articulate and convincing champion of the passionate life. Passion to Mr. Forster has many faces; indeed it is a whole way of life. It is the purpose of this paper to define the many different aspects of this Forsterian passion and to observe its development or denial in several characters of his selected fiction. It is difficult, as I write about E. M. Forster, to believe that he is in his eighty-sixth year and that he has not published a novel in forty years. It is difficult to accept these biological and literary facts because, even today, p?r,s° works retain a freshness and vitality that many later works of English fiction lack. What then gives these qualities to his fiction, some of which was written more than 40 years ago? Partly, it is because Mr. F«riis concerned with universal themes but it is also because he has managed to communicate some of the wonder and idealism of the child in a jaded century. He invites us to climb through to the other side of the hedge1 and begin to live. He is essentially didactic in his writings but his didactism is gentle and becomes less insistent, more subtle and tentative by the time of A Passage to India. -

Definitions of Child Abuse and Neglect

STATE STATUTES Current Through March 2019 WHAT’S INSIDE Defining child abuse or Definitions of Child neglect in State law Abuse and Neglect Standards for reporting Child abuse and neglect are defined by Federal Persons responsible for the child and State laws. At the State level, child abuse and neglect may be defined in both civil and criminal Exceptions statutes. This publication presents civil definitions that determine the grounds for intervention by Summaries of State laws State child protective agencies.1 At the Federal level, the Child Abuse Prevention and Treatment To find statute information for a Act (CAPTA) has defined child abuse and neglect particular State, as "any recent act or failure to act on the part go to of a parent or caregiver that results in death, https://www.childwelfare. serious physical or emotional harm, sexual abuse, gov/topics/systemwide/ or exploitation, or an act or failure to act that laws-policies/state/. presents an imminent risk of serious harm."2 1 States also may define child abuse and neglect in criminal statutes. These definitions provide the grounds for the arrest and prosecution of the offenders. 2 CAPTA Reauthorization Act of 2010 (P.L. 111-320), 42 U.S.C. § 5101, Note (§ 3). Children’s Bureau/ACYF/ACF/HHS 800.394.3366 | Email: [email protected] | https://www.childwelfare.gov Definitions of Child Abuse and Neglect https://www.childwelfare.gov CAPTA defines sexual abuse as follows: and neglect in statute.5 States recognize the different types of abuse in their definitions, including physical abuse, The employment, use, persuasion, inducement, neglect, sexual abuse, and emotional abuse. -

Suspicion of Motives Predicts Minorities' Responses to Positive Feedback in Interracial Interactions

UCSF UC San Francisco Previously Published Works Title Suspicion of Motives Predicts Minorities' Responses to Positive Feedback in Interracial Interactions. Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/2j8345b6 Journal Journal of experimental social psychology, 62 ISSN 0022-1031 Authors Major, Brenda Kunstman, Jonathan W Malta, Brenna D et al. Publication Date 2016 DOI 10.1016/j.jesp.2015.10.007 Peer reviewed eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California Journal of Experimental Social Psychology 62 (2016) 75–88 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Journal of Experimental Social Psychology journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/jesp Suspicion of motives predicts minorities' responses to positive feedback in interracial interactions☆,☆☆,☆☆☆ Brenda Major a,⁎, Jonathan W. Kunstman b,BrennaD.Maltac,PamelaJ.Sawyera, Sarah S.M. Townsend d, Wendy Berry Mendes e a University of California, Santa Barbara, United States b Miami University, United States c New York University, United States d University of Southern California, United States e University of California, San Francisco, United States HIGHLIGHTS • Anti-bias norms increase attributional ambiguity of feedback to minorities. • Some minorities suspect Whites’ positivity toward them is insincere. • Suspicion of motives predicts uncertainty, threat and decreased self-esteem. • Attributionally ambiguous positive feedback is threatening for minorities. • Suspicion that positive evaluations are insincere can have negative consequences. article info abstract -

“Spidey Sense”: Emotional Intelligence and Police Decision-Making at Domestic Incidents

Applying “spidey sense”: Emotional Intelligence and Police Decision-Making at Domestic Incidents Anne Eason This thesis is submitted in partial fulfilment of the Requirement’s for the award of the degree of Professional Doctorate of Criminal Justice Studies of the University of Portsmouth. September 2019 Declaration Whilst registered as a candidate for the above degree, I have not been registered for any other research award. The results and conclusions embodied in this thesis are the work of the named candidate and have not been submitted for any other academic award. Word count: 49,726 2 Abstract Chaos theory suggests a small act can have a powerful impact on future events. This research takes this suggestion and explores the decision-making of police officers at domestic violence incidents as just such an act that can have a long-term impact on victim(s) lives. Applying the concept of emotional intelligence as an assistive means for problem-solving and decision-making, this research aimed to find out how, or if, police officers draw upon emotional intelligence in their decision- making at domestic incidents and what value they place on its development within the force. Taking a qualitative approach, 27 police officers across four police areas in England were interviewed and the data, coded and categorised, in a thematic analysis that revealed four central themes forming a new ‘emotional intelligence competence’. Environmental competence is symbolic of policing practice that is adaptive and autonomous and as recommended, supporting officers develop this will frustrate the diminishment of emotional intelligence that reportedly occurs through longer-term policing experience. -

Social Work As an Emotional Labor: Management of Emotions in Social Work Profession

SOCIAL WORK AS AN EMOTIONAL LABOR: MANAGEMENT OF EMOTIONS IN SOCIAL WORK PROFESSION Associate Prof. Emine ÖZMETE* Abstract This paper provides a conceptual explanation of social work as emotional labor related to the interactions between social workers and their clients in human service organizations. Emotional labor is a relatively new term. It is about controlling emotions to conform to social and professionals norms. The concept of emotional labor offers researchers a lens through which these interactions can be conceived of as job demands rather than as a medium through which work tasks are accomplished or as informal social relations. This powerful insight has informed studies of interactive work in all its forms, as well as called attention to the many ways that interaction at work is organized, regulated, and enacted. Therefore understanding the interactions between clients and professional influences on the construction and regulation of emotion at work are important challenges for the social work profession. Key Words: Emotional labor, management of emotions, social work Özet Bu makalede insani hizmet örgütlerinde sosyal hizmet uzmanları ve müracatçılar arasındaki etkileşime dayalı olarak sosyal hizmetin duygusal bir iş olduğunu belirten kavramsal çerçeve açıklanmaktadır. Duygusal iş oldukça yeni bir kavramdır. Bu kavram, sosyal ve mesleki normlarla uyumlu olarak duyguların kontrol edilmesi ile ilişkilidir. Duygusal iş kavramı araştırmacılara basit bir şekilde informal sosyal ilişkiler ve yerine getirilmesi gereken bir işten daha çok iş taleplerinin gereği olarak ortaya çıkan etkileşimler için derinlemesine bir bakış açısı sunar. Bu güçlü bakış açısı günümüze değin yapılmış çalışmalarda etkleşime dayalı olarak planlanmış, düzenlenmiş ve gerçekleştirilmiş olan işler için kullanılmıştır. Bu nedenle müracatçılar ve meslek elemanları arasındaki etkileşimin iş yaşamında duyguların düzenlenmesi ve yapılandırılması üzerindeki etkisinin anlaşılması sosyal hizmet mesleği için önemli mücadele alanıdır. -

Examining the Effect of Childhood Animal Cruelty Motives on Recurrent Adult Violent Crimes Toward Humans

EXAMINING THE EFFECT OF CHILDHOOD ANIMAL CRUELTY MOTIVES ON RECURRENT ADULT VIOLENT CRIMES TOWARD HUMANS By Joshua C. Overton Approved: __________________________________ _________________________________ Christopher Hensley Tammy Garland Associate Professor of Criminal Justice Assistant Professor of Criminal Justice (Director of Thesis) (Committee Member) __________________________________ _________________________________ Karen McGuffee Herbert Burhenn Associate Professor of Legal Dean of the College of Assistant Studies Arts and Sciences (Committee Member) __________________________________ Gerald Ainsworth Dean of the Graduate School Examining the Effect of Childhood Animal Cruelty Motives on Recurrent Adult Violent Crimes Toward Humans A Thesis Presented for the Masters of Science Degree The University of Tennessee, Chattanooga Joshua C. Overton August 2011 Copyright © 2011 by Joshua C. Overton All rights reserved ii DEDICATION To my wife Sharon Overton Grandfather Raymond Maurice Burdette Mother Brenda Overton Father Gary Overton iii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I would like to express my deepest gratitude to Dr. Christopher Hensley for his support and willingness to assist in my thesis preparation. Dr. Hensley constantly encouraged me to pursue a graduate degree and was extremely helpful throughout my tenure in Criminal Justice. It was with his guidance that I was able to complete the thesis process. Additionally, I would like to thank Dr. Vic Bumphus for continually encouraging me to pursue a higher education degree and for his constant support and advice throughout my time in the Criminal Justice Department. I would also like to thank Dr. Tammy Garland and Professor Karen McGuffee for serving on my thesis committee. They were both extremely supportive and helpful during my time pursuing a graduate degree. Finally, I would like to thank the entire Criminal Justice Department at UTC for educating me at the highest level and making my time in Criminal Justice extremely enjoyable. -

Animal Cruelty Prosecution

SPECIAL TOPICS SERIES American Prosecutors Research Institute AnimalAnimal CrueltyCruelty ProsecutionProsecution OpportunitiesOpportunities forfor EarlyEarly ResponseResponse toto CrimeCrime andand InterpersonalInterpersonal ViolenceViolence Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention Office of Justice Programs U.S. Department of Justice American Prosecutors Research Institute 99 Canal Center Plaza, Suite 510 Alexandria,VA 22314 www.ndaa.org Thomas J. Charron President Roger Floren Chief of Staff Delores Heredia Ward Director, National Juvenile Justice Prosecution Center Debra Whitcomb Director, Grant Programs and Development © 2006 by the American Prosecutors Research Institute, the non-profit research, training and technical assistance affiliate of the National District Attorneys Association. This project was supported by Grant Number 2002-MU-MU-0003 awarded by the Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention, Office of Justice Programs, U. S. Department of Justice.This information is offered for educational purposes only and is not legal advice. Points of view or opinions in this publication are those of the authors and do not represent the official position or policies of the United States Department of Justice, the National District Attorneys Association, or the American Prosecutors Research Institute. SPECIAL TOPICS SERIES AnimalAnimal CrueltyCruelty ProsecutionProsecution Opportunities for Early Response to Crime and Interpersonal Violence July 2006 Randall Lockwood, Ph.D. Senior Vice President/ Anticruelty Initiatives -

Compassion and Sympathy As Moral Motivation Moral Philosophy Has Long Taken an Interest in the Emotions

Compassion and Sympathy as Moral Motivation Moral philosophy has long taken an interest in the emotions. Ever since Plato’s defense of the primacy of reason as a source of motiva- tion, moral philosophers have debated the proper role of emotion in the character of a good person and in the choice of individual actions. There are striking contrasts that can be drawn among the main tradi- tions in moral philosophy as to the role they assign to the emotions, and to the particular emotions that they evaluate positively and nega- tively. Here are some examples. Utilitarianism is often presented as a the- ory which simply articulates an ideal of sympathy, where the morally right action is the one that would be favored by someone who is equally sympathetic to the pleasure and pains of all sentient beings. And, on another level, utilitarianism tends to evaluate highly actions motivated by sympathy and compassion, and to evaluate negatively actions motivated by malice and spite. Kantianism (or deontology, as it is often called) has a completely different structure and, conse- quently, a different attitude towards the emotions. It conceives of morality as the self-imposed laws of rational agents, and no emotion is thought to be involved in the generation of these laws. It is true that Kant himself does find a special role for the emotion—if that is the right word—of respect for rational agents and for the laws they impose on themselves. But Kant seems to regard respect as a sort of effect within us of our own inscrutable moral freedom, and not as the source of moral legislation. -

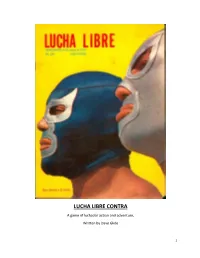

Lucha Libre Contra

LUCHA LIBRE CONTRA A game of luchador action and adventure, Written by Dave Glide 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION ……………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………. 3 Agendas & Principles; GM Moves; World & Adventures CHARACTER CREATION ………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………… 9 Concept; Stats; Roles; Moves; History; Fatigue; Glory; Experience & Reputation Levels CHARACTER ROLES ……………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………… 13 Tecnico; Rudo; Monstruo; High-Flyer; Extrema; Exotico GENERICO MOVES ………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………. 19 Rookie; Journeyman; Professional; Champion; Legend ADVANCED CHARACTER OPTIONS ………………………………………………………………………………………………………. 25 Starting Above “Rookie;” Cross-Role Moves; Alternative Characters; Character Creation Example TAKING ACTION …………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………… 29 Combat & Non-Combat Moves LUCHA COMBAT and CULTURE NOTES ………………………………………………………………………………………………… 41 Match Rules; Lucha Terminology; Optional Rules ENEMIES OF THE LUCHADORES …………………………………………………………………………………………………………… 48 Monster Stats; Henchman; Mythology and Death Traps SAMPLE VILLAINS ………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………… 52 SAMPLE DEATH TRAPS ………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………… 56 INSPIRATION ……………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………….. 58 FINAL WORD ……………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………….. 59 2 THE WORLD OF LUCHA LIBRE CONTRA In Lucha Libre Contra, players take on heroes. Young fans could thrill to El Santo’s the role of luchadores: masked Mexican adventures in