3D Chess Fide-Based RULES

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Combinatorics on the Chessboard

Combinatorics on the Chessboard Interactive game: 1. On regular chessboard a rook is placed on a1 (bottom-left corner). Players A and B take alternating turns by moving the rook upwards or to the right by any distance (no left or down movements allowed). Player A makes the rst move, and the winner is whoever rst reaches h8 (top-right corner). Is there a winning strategy for any of the players? Solution: Player B has a winning strategy by keeping the rook on the diagonal. Knight problems based on invariance principle: A knight on a chessboard has a property that it moves by alternating through black and white squares: if it is on a white square, then after 1 move it will land on a black square, and vice versa. Sometimes this is called the chameleon property of the knight. This is related to invariance principle, and can be used in problems, such as: 2. A knight starts randomly moving from a1, and after n moves returns to a1. Prove that n is even. Solution: Note that a1 is a black square. Based on the chameleon property the knight will be on a white square after odd number of moves, and on a black square after even number of moves. Therefore, it can return to a1 only after even number of moves. 3. Is it possible to move a knight from a1 to h8 by visiting each square on the chessboard exactly once? Solution: Since there are 64 squares on the board, a knight would need 63 moves to get from a1 to h8 by visiting each square exactly once. -

A Package to Print Chessboards

chessboard: A package to print chessboards Ulrike Fischer November 1, 2020 Contents 1 Changes 1 2 Introduction 2 2.1 Bugs and errors.....................................3 2.2 Requirements......................................4 2.3 Installation........................................4 2.4 Robustness: using \chessboard in moving arguments..............4 2.5 Setting the options...................................5 2.6 Saving optionlists....................................7 2.7 Naming the board....................................8 2.8 Naming areas of the board...............................8 2.9 FEN: Forsyth-Edwards Notation...........................9 2.10 The main parts of the board..............................9 3 Setting the contents of the board 10 3.1 The maximum number of fields........................... 10 1 3.2 Filling with the package skak ............................. 11 3.3 Clearing......................................... 12 3.4 Adding single pieces.................................. 12 3.5 Adding FEN-positions................................. 13 3.6 Saving positions..................................... 15 3.7 Getting the positions of pieces............................ 16 3.8 Using saved and stored games............................ 17 3.9 Restoring the running game.............................. 17 3.10 Changing the input language............................. 18 4 The look of the board 19 4.1 Units for lengths..................................... 19 4.2 Some words about box sizes.............................. 19 4.3 Margins......................................... -

53Rd WORLD CONGRESS of CHESS COMPOSITION Crete, Greece, 16-23 October 2010

53rd WORLD CONGRESS OF CHESS COMPOSITION Crete, Greece, 16-23 October 2010 53rd World Congress of Chess Composition 34th World Chess Solving Championship Crete, Greece, 16–23 October 2010 Congress Programme Sat 16.10 Sun 17.10 Mon 18.10 Tue 19.10 Wed 20.10 Thu 21.10 Fri 22.10 Sat 23.10 ICCU Open WCSC WCSC Excursion Registration Closing Morning Solving 1st day 2nd day and Free time Session 09.30 09.30 09.30 free time 09.30 ICCU ICCU ICCU ICCU Opening Sub- Prize Giving Afternoon Session Session Elections Session committees 14.00 15.00 15.00 17.00 Arrival 14.00 Departure Captains' meeting Open Quick Open 18.00 Solving Solving Closing Lectures Fairy Evening "Machine Show Banquet 20.30 Solving Quick Gun" 21.00 19.30 20.30 Composing 21.00 20.30 WCCC 2010 website: http://www.chessfed.gr/wccc2010 CONGRESS PARTICIPANTS Ilham Aliev Azerbaijan Stephen Rothwell Germany Araz Almammadov Azerbaijan Rainer Staudte Germany Ramil Javadov Azerbaijan Axel Steinbrink Germany Agshin Masimov Azerbaijan Boris Tummes Germany Lutfiyar Rustamov Azerbaijan Arno Zude Germany Aleksandr Bulavka Belarus Paul Bancroft Great Britain Liubou Sihnevich Belarus Fiona Crow Great Britain Mikalai Sihnevich Belarus Stewart Crow Great Britain Viktor Zaitsev Belarus David Friedgood Great Britain Eddy van Beers Belgium Isabel Hardie Great Britain Marcel van Herck Belgium Sally Lewis Great Britain Andy Ooms Belgium Tony Lewis Great Britain Luc Palmans Belgium Michael McDowell Great Britain Ward Stoffelen Belgium Colin McNab Great Britain Fadil Abdurahmanović Bosnia-Hercegovina Jonathan -

The Oldest Books on Modern Chess

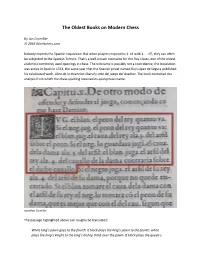

The Oldest Books on Modern Chess By Jon Crumiller © 2016 Worldchess.com Nobody expects the Spanish Inquisition. But when players respond to 1. e4 with 1. … e5, they can often be subjected to the Spanish Torture. That’s a well-known nickname for the Ruy López, one of the oldest and most commonly used openings in chess. The nickname is possibly not a coincidence; the Inquisition was active in Spain in 1561, the same year that the Spanish priest named Ruy López de Segura published his celebrated work, Libro de la Invencion liberal y Arte del juego del Axedrez. The book contained the analysis from which the chess opening received its eponymous name. Jonathan Crumiller The passage highlighted above can roughly be translated: White king’s pawn goes to the fourth. If black plays the king’s pawn to the fourth: white plays the king’s knight to the king’s bishop third, over the pawn. If black plays the queen’s knight to queen’s bishop third: white plays the king’s bishop to the fourth square of the contrary queen’s knight, opposed to that knight. Or in our modern chess language: 1. e4, e5 2. Nf3, Nc6 3. Bb5. Jonathan Crumiller On the right is how the Ruy López opening would have looked four centuries ago with a standard chess set and board in Spain. This Spanish chess set is one of my oldest complete sets (along with a companion wooden set of the same era). Jonathan Crumiller Here is the Ruy López as seen with that companion set displayed on a Spanish chessboard, also from the 1600’s. -

Proposal to Encode Heterodox Chess Symbols in the UCS Source: Garth Wallace Status: Individual Contribution Date: 2016-10-25

Title: Proposal to Encode Heterodox Chess Symbols in the UCS Source: Garth Wallace Status: Individual Contribution Date: 2016-10-25 Introduction The UCS contains symbols for the game of chess in the Miscellaneous Symbols block. These are used in figurine notation, a common variation on algebraic notation in which pieces are represented in running text using the same symbols as are found in diagrams. While the symbols already encoded in Unicode are sufficient for use in the orthodox game, they are insufficient for many chess problems and variant games, which make use of extended sets. 1. Fairy chess problems The presentation of chess positions as puzzles to be solved predates the existence of the modern game, dating back to the mansūbāt composed for shatranj, the Muslim predecessor of chess. In modern chess problems, a position is provided along with a stipulation such as “white to move and mate in two”, and the solver is tasked with finding a move (called a “key”) that satisfies the stipulation regardless of a hypothetical opposing player’s moves in response. These solutions are given in the same notation as lines of play in over-the-board games: typically algebraic notation, using abbreviations for the names of pieces, or figurine algebraic notation. Problem composers have not limited themselves to the materials of the conventional game, but have experimented with different board sizes and geometries, altered rules, goals other than checkmate, and different pieces. Problems that diverge from the standard game comprise a genre called “fairy chess”. Thomas Rayner Dawson, known as the “father of fairy chess”, pop- ularized the genre in the early 20th century. -

Reshevsky Wins Playoff, Qualifies for Interzonal Title Match Benko First in Atlantic Open

RESHEVSKY WINS PLAYOFF, TITLE MATCH As this issue of CHESS LIFE goes to QUALIFIES FOR INTERZONAL press, world champion Mikhail Botvinnik and challenger Tigran Petrosian are pre Grandmaster Samuel Reshevsky won the three-way playoff against Larry paring for the start of their match for Evans and William Addison to finish in third place in the United States the chess championship of the world. The contest is scheduled to begin in Moscow Championship and to become the third American to qualify for the next on March 21. Interzonal tournament. Reshevsky beat each of his opponents once, all other Botvinnik, now 51, is seventeen years games in the series being drawn. IIis score was thus 3-1, Evans and Addison older than his latest challenger. He won the title for the first time in 1948 and finishing with 1 %-2lh. has played championship matches against David Bronstein, Vassily Smyslov (three) The games wcre played at the I·lerman Steiner Chess Club in Los Angeles and Mikhail Tal (two). He lost the tiUe to Smyslov and Tal but in each case re and prizes were donated by the Piatigorsky Chess Foundation. gained it in a return match. Petrosian became the official chal By winning the playoff, Heshevsky joins Bobby Fischer and Arthur Bisguier lenger by winning the Candidates' Tour as the third U.S. player to qualify for the next step in the World Championship nament in 1962, ahead of Paul Keres, Ewfim Geller, Bobby Fischer and other cycle ; the InterzonaL The exact date and place for this event havc not yet leading contenders. -

Origins of Chess Protochess, 400 B.C

Origins of Chess Protochess, 400 B.C. to 400 A.D. by G. Ferlito and A. Sanvito FROM: The Pergamon Chess Monthly September 1990 Volume 55 No. 6 The game of chess, as we know it, emerged in the North West of ancient India around 600 A.D. (1) According to some scholars, the game of chess reached Persia at the time of King Khusrau Nushirwan (531/578 A.D.), though some others suggest a later date around the time of King Khusrau II Parwiz (590/628 A.D.) (2) Reading from the old texts written in Pahlavic, the game was originally known as "chatrang". With the invasion of Persia by the Arabs (634/651 A.D.), the game’s name became "shatranj" because the phonetic sounds of "ch" and "g" do not exist in Arabic language. The game spread towards the Mediterranean coast of Africa with the Islamic wave of military expansion and then crossed over to Europe. However, other alternative routes to some parts of Europe may have been used by other populations who were playing the game. At the moment, this "Indian, Persian, Islamic" theory on the origin of the game is accepted by the majority of scholars, though it is fair to mention here the work of J. Needham and others who suggested that the historical chess of seventh century India was descended from a divinatory game (or ritual) in China. (3) On chess theories, the most exhaustive account founded on deep learning and many years’ studies is the A History of Chess by the English scholar, H.J.R. -

![[Math.HO] 4 Oct 2007 Computer Analysis of the Two Versions](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/3027/math-ho-4-oct-2007-computer-analysis-of-the-two-versions-1983027.webp)

[Math.HO] 4 Oct 2007 Computer Analysis of the Two Versions

Computer analysis of the two versions of Byzantine chess Anatole Khalfine and Ed Troyan University of Geneva, 24 Rue de General-Dufour, Geneva, GE-1211, Academy for Management of Innovations, 16a Novobasmannaya Street, Moscow, 107078 e-mail: [email protected] July 7, 2021 Abstract Byzantine chess is the variant of chess played on the circular board. In the Byzantine Empire of 11-15 CE it was known in two versions: the regular and the symmetric version. The difference between them: in the latter version the white queen is placed on dark square. However, the computer analysis reveals the effect of this ’perturbation’ as well as the basis of the best winning strategy in both versions. arXiv:math/0701598v2 [math.HO] 4 Oct 2007 1 Introduction Byzantine chess [1], invented about 1000 year ago, is one of the most inter- esting variations of the original chess game Shatranj. It was very popular in Byzantium since 10 CE A.D. (and possible created there). Princess Anna Comnena [2] tells that the emperor Alexius Comnenus played ’Zatrikion’ - so Byzantine scholars called this game. Now it is known under the name of Byzantine chess. 1 Zatrikion or Byzantine chess is the first known attempt to play on the circular board instead of rectangular. The board is made up of four concentric rings with 16 squares (spaces) per ring giving a total of 64 - the same as in the standard 8x8 chessboard. It also contains the same pieces as its parent game - most of the pieces having almost the same moves. In other words divide the normal chessboard in two halves and make a closed round strip [1]. -

Courier Chess Rick Knowlton 13 News in Brief / CCI Meetings 17 Advertisements 18 CCI Diary / CCI Information 19 Advertisement 20

The CHESS COLLECTOR VOL XVIII NO 1. 2009 The Chess Collector. Vol XVIII No1. 2009 CONTENTS Editors / Members Comments Jim Joannou 2 Your Move!. Members Page Jim Joannou 3 Updates on Previous Issues Gianfelice Ferlito 4 William Shakespear the Chess Player Gareth Williams 5 Special Announcement Jim Joannou 7 Pole Lathe Turned Chessmen Alan Dewey 9 Courier Chess Rick Knowlton 13 News in Brief / CCI Meetings 17 Advertisements 18 CCI Diary / CCI Information 19 Advertisement 20 Editor’s Comment Front Cover Wall Murial in the main hall of “Chess Despite the talk of recession around the City”, Elista, Kalmykia. Chess city was world, there has still been quite a lot hap- built by FIDE president, Kirsan Ilyumzhi- pening in the chess collecting world with nov in 1998. It was left unused for several exhibitions, auctions and, of course, e- years, but is now being used regularly to Bay. (Although good sets seem to have host many chess tournaments, including dried up more recently on e-Bay) the World championships in 2006. In this issue we are announcing a new de- ~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~ velopment in the CCI and this magazine! Members Comments Read on to find out what’s happening. CCI Member Mike Wiltshire (CCI UK We recieved three articles by CCI mem- Executive) is pictured below after coming bers, and several advertising requests, so joint second with Ellen Carlsen (sister of space was limited this time round and I Magnus Carlsen) in the amateur tourna- was only able to fit in a minimal amount ment of the recent 7th Gibtelcom chess of smaller items like “News in Brief” or festival in Gibraltar. -

The Chess Players

The Chess Players A Project Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Liberal Studies by Gerry A. Wolfson-Grande May, 2013 Mentor: Dr. Philip F. Deaver Reader: Dr. Steve Phelan Rollins College Hamilton Holt School Master of Liberal Studies Program Winter Park, Florida NOTE TO THE READER: For my thesis project, I have written a novel-in-stories called The Chess Players. This companion piece, “A Game for All Reasons: Musings on the Interdisciplinary Nature of Chess,” is intended to supplement the creative narrative with my analyses assembled over the course of the MLS program. A GAME FOR ALL REASONS: Musings on the Interdisciplinary Nature of Chess By Gerry A. Wolfson-Grande May, 2013 TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction ......................................................................................................................... 1 Enter the Queen................................................................................................................... 3 Art, Improvisation and Randomness................................................................................. 14 Fortune and Her Wheel: Chess in the Book of the Duchess and the Knight’s Tale ......... 26 Conclusion ........................................................................................................................ 40 Bibliography ..................................................................................................................... 42 Artwork ............................................................................................................................ -

Introduction

Introduction One day, at the end of a group lesson on basic rook endgame positions that I had just given at my club, one of my students, Hocine, aged about ten, came up to ask me: «But what is the point of knowing the Lucena or Philidor positions? I never get that far. Often I lose before the ending because I didn’t know the opening. Teach us the Sicilian Defence instead, it will be more useful». Of course, I tried to make him understand that if he lost it was not always, or even often, because of his short comings in the opening. I also explained to him that learning the endgames was essential to progress in the other phases of the game, and that the positions of Philidor or Lucena (to name but these two) should be part of the basic knowledge of any chess player, in much the same way that a musician must inevitably study the works of Mozart and Beethoven, sooner or later. However, I came to realize that I had great difficulty in making him see reason. Meanwhile Nicolas, another of my ten-year-old students, regularly arrives at classes with a whole bunch of new names of openings that he gleaned here and there on the internet, and that he proudly displays to his club mates. They remain amazed by all these baroque-sounding opening names, and they have a deep respect for his encyclopaedic knowledge. For my part, I try to behave like a teacher by explaining to Nicolas that his intellectual curiosity is commendable, but that knowledge of the Durkin Attack, the Elephant Gambit or the Mexican Defence, as exciting as they might be, has a rather limited practical interest at the board. -

Rules for Chess

Rules for Chess Object of the Chess Game It's rather simple; there are two players with one player having 16 black or dark color chess pieces and the other player having 16 white or light color chess pieces. The chess players move on a square chessboard made up of 64 individual squares consisting of 32 dark squares and 32 light squares. Each chess piece has a defined starting point or square with the dark chess pieces aligned on one side of the board and the light pieces on the other. There are 6 different types of chess pieces, each with it's own unique method to move on the chessboard. The chess pieces are used to both attack and defend from attack, against the other players chessmen. Each player has one chess piece called the king. The ultimate objective of the game is to capture the opponents king. Having said this, the king will never actually be captured. When either sides king is trapped to where it cannot move without being taken, it's called "checkmate" or the shortened version "mate". At this point, the game is over. The object of playing chess is really quite simple, but mastering this game of chess is a totally different story. Chess Board Setup Now that you have a basic concept for the object of the chess game, the next step is to get the the chessboard and chess pieces setup according to the rules of playing chess. Lets start with the chess pieces. The 16 chess pieces are made up of 1 King, 1 queen, 2 bishops, 2 knights, 2 rooks, and 8 pawns.