The Chess Players

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Computer Analysis of World Chess Champions 65

Computer Analysis of World Chess Champions 65 COMPUTER ANALYSIS OF WORLD CHESS CHAMPIONS1 Matej Guid2 and Ivan Bratko2 Ljubljana, Slovenia ABSTRACT Who is the best chess player of all time? Chess players are often interested in this question that has never been answered authoritatively, because it requires a comparison between chess players of different eras who never met across the board. In this contribution, we attempt to make such a comparison. It is based on the evaluation of the games played by the World Chess Champions in their championship matches. The evaluation is performed by the chess-playing program CRAFTY. For this purpose we slightly adapted CRAFTY. Our analysis takes into account the differences in players' styles to compensate the fact that calm positional players in their typical games have less chance to commit gross tactical errors than aggressive tactical players. Therefore, we designed a method to assess the difculty of positions. Some of the results of this computer analysis might be quite surprising. Overall, the results can be nicely interpreted by a chess expert. 1. INTRODUCTION Who is the best chess player of all time? This is a frequently posed and interesting question, to which there is no well founded, objective answer, because it requires a comparison between chess players of different eras who never met across the board. With the emergence of high-quality chess programs a possibility of such an objective comparison arises. However, so far computers were mostly used as a tool for statistical analysis of the players' results. Such statistical analyses often do neither reect the true strengths of the players, nor do they reect their quality of play. -

Combinatorics on the Chessboard

Combinatorics on the Chessboard Interactive game: 1. On regular chessboard a rook is placed on a1 (bottom-left corner). Players A and B take alternating turns by moving the rook upwards or to the right by any distance (no left or down movements allowed). Player A makes the rst move, and the winner is whoever rst reaches h8 (top-right corner). Is there a winning strategy for any of the players? Solution: Player B has a winning strategy by keeping the rook on the diagonal. Knight problems based on invariance principle: A knight on a chessboard has a property that it moves by alternating through black and white squares: if it is on a white square, then after 1 move it will land on a black square, and vice versa. Sometimes this is called the chameleon property of the knight. This is related to invariance principle, and can be used in problems, such as: 2. A knight starts randomly moving from a1, and after n moves returns to a1. Prove that n is even. Solution: Note that a1 is a black square. Based on the chameleon property the knight will be on a white square after odd number of moves, and on a black square after even number of moves. Therefore, it can return to a1 only after even number of moves. 3. Is it possible to move a knight from a1 to h8 by visiting each square on the chessboard exactly once? Solution: Since there are 64 squares on the board, a knight would need 63 moves to get from a1 to h8 by visiting each square exactly once. -

A Package to Print Chessboards

chessboard: A package to print chessboards Ulrike Fischer November 1, 2020 Contents 1 Changes 1 2 Introduction 2 2.1 Bugs and errors.....................................3 2.2 Requirements......................................4 2.3 Installation........................................4 2.4 Robustness: using \chessboard in moving arguments..............4 2.5 Setting the options...................................5 2.6 Saving optionlists....................................7 2.7 Naming the board....................................8 2.8 Naming areas of the board...............................8 2.9 FEN: Forsyth-Edwards Notation...........................9 2.10 The main parts of the board..............................9 3 Setting the contents of the board 10 3.1 The maximum number of fields........................... 10 1 3.2 Filling with the package skak ............................. 11 3.3 Clearing......................................... 12 3.4 Adding single pieces.................................. 12 3.5 Adding FEN-positions................................. 13 3.6 Saving positions..................................... 15 3.7 Getting the positions of pieces............................ 16 3.8 Using saved and stored games............................ 17 3.9 Restoring the running game.............................. 17 3.10 Changing the input language............................. 18 4 The look of the board 19 4.1 Units for lengths..................................... 19 4.2 Some words about box sizes.............................. 19 4.3 Margins......................................... -

53Rd WORLD CONGRESS of CHESS COMPOSITION Crete, Greece, 16-23 October 2010

53rd WORLD CONGRESS OF CHESS COMPOSITION Crete, Greece, 16-23 October 2010 53rd World Congress of Chess Composition 34th World Chess Solving Championship Crete, Greece, 16–23 October 2010 Congress Programme Sat 16.10 Sun 17.10 Mon 18.10 Tue 19.10 Wed 20.10 Thu 21.10 Fri 22.10 Sat 23.10 ICCU Open WCSC WCSC Excursion Registration Closing Morning Solving 1st day 2nd day and Free time Session 09.30 09.30 09.30 free time 09.30 ICCU ICCU ICCU ICCU Opening Sub- Prize Giving Afternoon Session Session Elections Session committees 14.00 15.00 15.00 17.00 Arrival 14.00 Departure Captains' meeting Open Quick Open 18.00 Solving Solving Closing Lectures Fairy Evening "Machine Show Banquet 20.30 Solving Quick Gun" 21.00 19.30 20.30 Composing 21.00 20.30 WCCC 2010 website: http://www.chessfed.gr/wccc2010 CONGRESS PARTICIPANTS Ilham Aliev Azerbaijan Stephen Rothwell Germany Araz Almammadov Azerbaijan Rainer Staudte Germany Ramil Javadov Azerbaijan Axel Steinbrink Germany Agshin Masimov Azerbaijan Boris Tummes Germany Lutfiyar Rustamov Azerbaijan Arno Zude Germany Aleksandr Bulavka Belarus Paul Bancroft Great Britain Liubou Sihnevich Belarus Fiona Crow Great Britain Mikalai Sihnevich Belarus Stewart Crow Great Britain Viktor Zaitsev Belarus David Friedgood Great Britain Eddy van Beers Belgium Isabel Hardie Great Britain Marcel van Herck Belgium Sally Lewis Great Britain Andy Ooms Belgium Tony Lewis Great Britain Luc Palmans Belgium Michael McDowell Great Britain Ward Stoffelen Belgium Colin McNab Great Britain Fadil Abdurahmanović Bosnia-Hercegovina Jonathan -

A Semiotic Analysis on Signs of the English Chess Game

1 A Semiotic Analysis on Signs of the English Chess Game M. I. Andi Purnomo, Drs. Wisasongko, M.A., Hat Pujiati, S.S., M.A. English Department, Faculty of Letter, Jember University Jln. Kalimantan 37, Jember 68121 E-mail: [email protected] Abstract This thesis discusses about English Chess Game through Roland Barthes's Myth. In this thesis, I use documentary technique as method of analysis. The analysis is done by the observation of the rules, colors, and images of the English chess game. In addition, chessman and chess formation are analyzed using syntagmatic and paradigmatic relation theory to explore the correlation between symbols of the English chess game with the existence of Christian in the middle age of England. The result of this thesis shows the relation of English chess game with the history of England in the middle age where Christian ideology influences the social, military, and government political life of the English empire. Keywords: chessman, chess piece, bishops, king, knights, pawns, queen, rooks. Introduction Then, the game spread into Europe. Around 1200, the game was established in Britain and the name of “Chess” begins Game is an activity that is done by people for some (Shenk, 2006:51). It means chess spread to English during purposes. Some people use the game as a medium of the Middle Ages. The Middle Age of English begins around interaction with other people. Others use the game as the 1066 – 1485 (www.middle-ages.org.uk). At that time, the activity of spending leisure time. Others use the game as the Christian dominated the whole empire and automatically the major activity for professional. -

Sarajevo 1967 ° "' 1 '"

Grondmaster ayme, lefl, explafntnq the qallle 01 d»eu to 80"011, c.nter, and USSR Champion Stein, Byrne later floated SteIn 10 anOfher leuon o"er the board. accountmq tor Sleln's only lou 01 lhe lournamenl, SARAJEVO 1967 I 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 A 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 W L D !: ~~::: :::::::::::::::::::::.:.... .::: :' .' ...: . ~ ~~, ---.-~;.-.::~;--:~;-"~,==~: =~~f. =~"tl =j~~=;~t="ii"'\'----;.~:;:--;"-;-·I - ::- -;:===-;~'----;~'---";:""~=- 10 ~ .4- ~ 3. tknko , If.! Y.i: % 0 I 0 1 1 I ~ I \ _ ;-1 _~'~ ,;--;;-, - \1)-5 x 1h 'h ':-l - '--'' 1 I I 1 'h I 0 I ,';-,,'c-- -:';-_-- 1().5_ °1 '""' 1h x 0 0 n 1 n I ¥, I 1 1 I ,..' .....;:3_ ~ 9Ik.5 ~ h 1 x I,i h ~ 1 n h I I,i 1;.--:1_ _ 5 1 9 9h . ~~ ° "1 h 1 I,i x 0 I 'h 0 1 "':"''-''''7----:-1 t 6" 5'- - 8'7 .6% o o lit liz 1 x 1,1: .., .., 1 "':t I t ¥l -.' , 2 ~ 81.1 f1lh 1 0 0 n 0 If. :< 0 0 1 J I n _ -;-I _ ';--;-6_ ,_ _ ,.. - 11 Duc1n tcin .. .. .... ... n ~ ~ ~ ~ : ~ "~'- : : ~ ~ ~ --,~,,-:~:-~ ----.-~ :: ~! 12. Ja.noS('vic .... ... ... ... .. ~_-;";... _~ ~ _Ifl "1 ;;:0'--;,;..0 _ 0,,-:"':-"''7--;;:''--''''' 1 ~"''-.;.I _ _.;:-' _ ;!i 8 f.. 9 13. Pict%.Sch ................................... \o!t Vr 'tit;. _ ";. ,-~O:- 0 n 'fl 0 0 . __1 'h x 0 1:'.1 0 1 6 --;8- - - 5- 10 14. Bogdanuvic .. .................. Y.t 0 0 0 0 lit Yt 0 0 Yt 1 0 I x 0 h 2 8 5 _ _ " "1.100" :~ : ~:~;:~. -

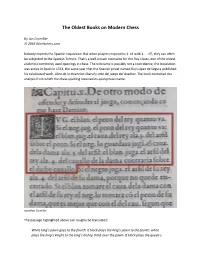

The Oldest Books on Modern Chess

The Oldest Books on Modern Chess By Jon Crumiller © 2016 Worldchess.com Nobody expects the Spanish Inquisition. But when players respond to 1. e4 with 1. … e5, they can often be subjected to the Spanish Torture. That’s a well-known nickname for the Ruy López, one of the oldest and most commonly used openings in chess. The nickname is possibly not a coincidence; the Inquisition was active in Spain in 1561, the same year that the Spanish priest named Ruy López de Segura published his celebrated work, Libro de la Invencion liberal y Arte del juego del Axedrez. The book contained the analysis from which the chess opening received its eponymous name. Jonathan Crumiller The passage highlighted above can roughly be translated: White king’s pawn goes to the fourth. If black plays the king’s pawn to the fourth: white plays the king’s knight to the king’s bishop third, over the pawn. If black plays the queen’s knight to queen’s bishop third: white plays the king’s bishop to the fourth square of the contrary queen’s knight, opposed to that knight. Or in our modern chess language: 1. e4, e5 2. Nf3, Nc6 3. Bb5. Jonathan Crumiller On the right is how the Ruy López opening would have looked four centuries ago with a standard chess set and board in Spain. This Spanish chess set is one of my oldest complete sets (along with a companion wooden set of the same era). Jonathan Crumiller Here is the Ruy López as seen with that companion set displayed on a Spanish chessboard, also from the 1600’s. -

Proposal to Encode Heterodox Chess Symbols in the UCS Source: Garth Wallace Status: Individual Contribution Date: 2016-10-25

Title: Proposal to Encode Heterodox Chess Symbols in the UCS Source: Garth Wallace Status: Individual Contribution Date: 2016-10-25 Introduction The UCS contains symbols for the game of chess in the Miscellaneous Symbols block. These are used in figurine notation, a common variation on algebraic notation in which pieces are represented in running text using the same symbols as are found in diagrams. While the symbols already encoded in Unicode are sufficient for use in the orthodox game, they are insufficient for many chess problems and variant games, which make use of extended sets. 1. Fairy chess problems The presentation of chess positions as puzzles to be solved predates the existence of the modern game, dating back to the mansūbāt composed for shatranj, the Muslim predecessor of chess. In modern chess problems, a position is provided along with a stipulation such as “white to move and mate in two”, and the solver is tasked with finding a move (called a “key”) that satisfies the stipulation regardless of a hypothetical opposing player’s moves in response. These solutions are given in the same notation as lines of play in over-the-board games: typically algebraic notation, using abbreviations for the names of pieces, or figurine algebraic notation. Problem composers have not limited themselves to the materials of the conventional game, but have experimented with different board sizes and geometries, altered rules, goals other than checkmate, and different pieces. Problems that diverge from the standard game comprise a genre called “fairy chess”. Thomas Rayner Dawson, known as the “father of fairy chess”, pop- ularized the genre in the early 20th century. -

Multilinear Algebra and Chess Endgames

Games of No Chance MSRI Publications Volume 29, 1996 Multilinear Algebra and Chess Endgames LEWIS STILLER Abstract. This article has three chief aims: (1) To show the wide utility of multilinear algebraic formalism for high-performance computing. (2) To describe an application of this formalism in the analysis of chess endgames, and results obtained thereby that would have been impossible to compute using earlier techniques, including a win requiring a record 243 moves. (3) To contribute to the study of the history of chess endgames, by focusing on the work of Friedrich Amelung (in particular his apparently lost analysis of certain six-piece endgames) and that of Theodor Molien, one of the founders of modern group representation theory and the first person to have systematically numerically analyzed a pawnless endgame. 1. Introduction Parallel and vector architectures can achieve high peak bandwidth, but it can be difficult for the programmer to design algorithms that exploit this bandwidth efficiently. Application performance can depend heavily on unique architecture features that complicate the design of portable code [Szymanski et al. 1994; Stone 1993]. The work reported here is part of a project to explore the extent to which the techniques of multilinear algebra can be used to simplify the design of high- performance parallel and vector algorithms [Johnson et al. 1991]. The approach is this: Define a set of fixed, structured matrices that encode architectural primitives • of the machine, in the sense that left-multiplication of a vector by this matrix is efficient on the target architecture. Formulate the application problem as a matrix multiplication. -

Hypermodern Game of Chess the Hypermodern Game of Chess

The Hypermodern Game of Chess The Hypermodern Game of Chess by Savielly Tartakower Foreword by Hans Ree 2015 Russell Enterprises, Inc. Milford, CT USA 1 The Hypermodern Game of Chess The Hypermodern Game of Chess by Savielly Tartakower © Copyright 2015 Jared Becker ISBN: 978-1-941270-30-1 All Rights Reserved No part of this book maybe used, reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any manner or form whatsoever or by any means, electronic, electrostatic, magnetic tape, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the express written permission from the publisher except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles or reviews. Published by: Russell Enterprises, Inc. PO Box 3131 Milford, CT 06460 USA http://www.russell-enterprises.com [email protected] Translated from the German by Jared Becker Editorial Consultant Hannes Langrock Cover design by Janel Norris Printed in the United States of America 2 The Hypermodern Game of Chess Table of Contents Foreword by Hans Ree 5 From the Translator 7 Introduction 8 The Three Phases of A Game 10 Alekhine’s Defense 11 Part I – Open Games Spanish Torture 28 Spanish 35 José Raúl Capablanca 39 The Accumulation of Small Advantages 41 Emanuel Lasker 43 The Canticle of the Combination 52 Spanish with 5...Nxe4 56 Dr. Siegbert Tarrasch and Géza Maróczy as Hypermodernists 65 What constitutes a mistake? 76 Spanish Exchange Variation 80 Steinitz Defense 82 The Doctrine of Weaknesses 90 Spanish Three and Four Knights’ Game 95 A Victory of Methodology 95 Efim Bogoljubow -

Birth of the Chess Queen C Marilyn Yalom for Irv, Who Introduced Me to Chess and Other Wonders Contents

A History Birth of the Chess Queen C Marilyn Yalom For Irv, who introduced me to chess and other wonders Contents Acknowledgments viii Introduction xii Selected Rulers of the Period xx part 1 • the mystery of the chess queen’ s birth One Chess Before the Chess Queen 3 Two Enter the Queen! 15 Three The Chess Queen Shows Her Face 29 part 2 • spain, italy, and germany Four Chess and Queenship in Christian Spain 39 Five Chess Moralities in Italy and Germany 59 part 3 • france and england Six Chess Goes to France and England 71 v • contents Seven Chess and the Cult of the Virgin Mary 95 Eight Chess and the Cult of Love 109 part 4 • scandinavia and russia Nine Nordic Queens, On and Off the Board 131 Ten Chess and Women in Old Russia 151 part 5 • power to the queen Eleven New Chess and Isabella of Castile 167 Twelve The Rise of “Queen’s Chess” 187 Thirteen The Decline of Women Players 199 Epilogue 207 Notes 211 Index 225 About the Author Praise Other Books by Marilyn Yalom Credits Cover Copyright About the Publisher Waking Piece The world dreams in chess Kibitzing like lovers Pawn’s queened redemption L is a forked path only horses lead. Rook and King castling for safety Bishop boasting of crossways slide. Echo of Orbit: starless squared sky. She alone moves where she chooses. Protecting helpless monarch, her bidden skill. Attacking schemers, plotters, blundered all. Game eternal. War breaks. She enters. Check mate. Hail Queen. How we crave Her majesty. —Gary Glazner Acknowledgments This book would not have been possible without the vast philo- logical, archaeological, literary, and art historical research of pre- vious writers, most notably from Germany and England. -

Ancient Chess Turns Moving One Piece in Each Turn

About this Booklet How to Print: This booklet will print best on card stock (110 lb. paper), but can also be printed on regular (20 lb.) paper. Do not print Page 1 (these instructions). First, have your printer print Page 2. Then load that same page back into your printer to be printed on the other side and print Page 3. When you load the page back into your printer, be sure tha t the top and bottom of the pages are oriented correctly. Permissions: You may print this booklet as often as you like, for p ersonal purposes. You may also print this booklet to be included with a game which is sold to another party. You may distribute this booklet, in printed or electronic form freely, not for profit. If this booklet is distributed, it may not be changed in an y way. All copyright and contact information must be kept intact. This booklet may not be sold for profit, except as mentioned a bove, when included in the sale of a board game. To contact the creator of this booklet, please go to the “contact” page at www.AncientChess.com Playing the Game A coin may be tossed to decide who goes first, and the players take Ancient Chess turns moving one piece in each turn. If a player’s King is threatened with capture, “ check” (Persian: “Shah”) is declared, and the player must move so that his King is n o longer threatened. If there is no possible move to relieve the King of the threat, he is in “checkmate” (Persian: “shahmat,” meaning, “the king is at a loss”).