Hypermodern Game of Chess the Hypermodern Game of Chess

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

1. Development

By Natalie & Leon Taylor 1. DEVELOPMENT ID Shelf Title Author Brief Description No. No. 1 1.1 Chess Made Easy C.J.S. Purdy & G. Aimed for beginners, Koshnitsky 1942, 64 pages. 2 1.2 The Game of Chess H.Golombek Advance from beginner, 1945, 255pages 3 1.3 A Guide to Chess Ed.Gerard & C. Advance from beginner Verviers 1969, 156 pages. 4 1.4 My System Aron Nimzovich Theory of chess to improve yourself 1973, 372 pages 5 1.5 Pawn Power in Chess Hans Kmoch Chess strategy using pawns. 1969, 300 pages 6 1.6 The Most Instructive Games Irving Chernev 62 annotated masterpieces of modern chess strat- of Chess Ever Played egy. 1972, 277 pages 7 1.7 The Development of Chess Dr. M. Euwe Annotated games explaining positional play, Style combination & analysis. 1968, 152pgs 8 1.8 Three Steps to Chess MasteryA.S. Suetin Examples of modern Grandmaster play to im- prove your playing strength. 1982, 188pgs 9 1.9 Grandmasters of Chess Harold C. Schonberg A history of modern chess through the lives of these great players. 1973, 302 pages 10 1.10 Grandmaster Preparation L. Polugayevsky How to prepare technically and psychologically for decisive encounters where everything is at stake. 1981, 232 pages 11 1.11 Grandmaster Performance L. Polugayevsky 64 games selected to give a clear impression of how victory is gained. 1984, 174 pages 12 1.12 Learn from the Grandmasters Raymond D. Keene A wide spectrum of games by a no. of players an- notated from different angles. 1975, 120 pgs 13 1.13 The Modern Chess Sacrifice Leonid Shamkovich ‘A thousand paths lead to delusion, but only one to the truth.’ 1980, 214 pages 14 1.14 Blunders & Brilliancies Ian Mullen and Moe Over 250 excellent exercises to asses your apti- Moss tude for brilliancy and blunder. -

CR1951 02.Pdf

FEBRUARY 1951 COLLEGIATE (S,'I' Pllge 34) SO CENTS Subscription Rate ONE YEAR 54.75 This is bow it hallllened: a ~I'aw~ " N the previous article, we were con this desperate resource: "Look, Vidmar, I sidering Hubillstein'g reludance to if the experts say the game is a draw, I'll agree to a dmw in positiolls which were abIde by their opinion," This fancy way "hopelessly" drawn. A curiotls instance of of sayiag "No" as painlessly as possible was effective beca,lse Vidmar, thanks to this sort turned up in his game with It WIlS in this position that Gilg, to Kmoch in Budapest in 1926. A wild mid· his keen sense of humor, was so amused at Rubinstein's tartful obllqueness that move, offered a draw \vhich had to be re dIe game led to a Queen and Pawn end fused by orders of the powers that be. ing in which Kmoch finally I'oreed per he found it relatively easy to resign him self to defeat. Gilg-·possibly irritllted by the "refusal." petual check. as Sllielmanll hints in the tournament That is to say, he gave a cheek and of· book-played: fered a draw with the remark that he NOTHEH master with a particularly eould force olle in any event. The situu A_ emphatic aversion for draws was Ru· 1 Q-KS lion was absurdly simple; no variations, dolph Spielmann, whose hero-fO!' more The move lost a Pawn; but, in view of no complications, no possibilities what reasons than one-was Tchigorin, the White's generally inferior position-notl' ever. -

Life & Games Akiva Rubinstein

The Life & Games of Akiva Rubinstein Volume 2: The Later Years Second Edition by John Donaldson & Nikolay Minev 2011 Russell Enterprises, Inc. Milford, CT USA 1 The Life & Games of Akiva Rubinstein: The Later Years The Life & Games of Akiva Rubinstein Volume 2: The Later Years Second Edition ISBN: 978-1-936490-39-4 © Copyright 2011 John Donaldson and Nikolay Minev All Rights Reserved No part of this book may be used, reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any manner or form whatsoever or by any means, elec- tronic, electrostatic, magnetic tape, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the express written permission from the publisher except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles or reviews. Published by: Russell Enterprises, Inc. P.O. Box 3131 Milford, CT 06460 USA http://www.russell-enterprises.com [email protected] Printed in the United States of America 2 Table of Contents Introduction to the 2nd Edition 7 Rubinstein: 1921-1961 12 A Rubinstein Sampler 28 1921 Göteborg 29 The Hague 34 Triberg 44 1922 London 53 Hastings 62 Teplitz-Schönau 72 Vienna 83 1923 Hastings 96 Carlsbad 100 Mährisch-Ostrau 113 1924 Meran 120 Southport 129 Berlin 134 1925 London 137 Baden-Baden 138 Marienbad 153 Breslau 161 Moscow 165 3 The Life & Games of Akiva Rubinstein: The Later Years 1926 Semmering 176 Dresden 189 Budapest 196 Hannover 203 Berlin 207 1927 àyGĨ 212 Warsaw 221 1928 Bad Kissingen 223 Berlin 229 1929 Ramsgate 238 Carlsbad 242 Budapest 260 5RJDãND6ODWLQD 265 1930 San Remo 273 Antwerp (Belgian -

Opening Moves - Player Facts

DVD Chess Rules Chess puzzles Classic games Extras - Opening moves - Player facts General Rules The aim in the game of chess is to win by trapping your opponent's king. White always moves first and players take turns moving one game piece at a time. Movement is required every turn. Each type of piece has its own method of movement. A piece may be moved to another position or may capture an opponent's piece. This is done by landing on the appropriate square with the moving piece and removing the defending piece from play. With the exception of the knight, a piece may not move over or through any of the other pieces. When the board is set up it should be positioned so that the letters A-H face both players. When setting up, make sure that the white queen is positioned on a light square and the black queen is situated on a dark square. The two armies should be mirror images of one another. Pawn Movement Each player has eight pawns. They are the least powerful piece on the chess board, but may become equal to the most powerful. Pawns always move straight ahead unless they are capturing another piece. Generally pawns move only one square at a time. The exception is the first time a pawn is moved, it may move forward two squares as long as there are no obstructing pieces. A pawn cannot capture a piece directly in front of him but only one at a forward angle. When a pawn captures another piece the pawn takes that piece’s place on the board, and the captured piece is removed from play If a pawn gets all the way across the board to the opponent’s edge, it is promoted. -

White Knight Review Chess E-Magazine January/February - 2012 Table of Contents

Chess E-Magazine Interactive E-Magazine Volume 3 • Issue 1 January/February 2012 Chess Gambits Chess Gambits The Immortal Game Canada and Chess Anderssen- Vs. -Kieseritzky Bill Wall’s Top 10 Chess software programs C Seraphim Press White Knight Review Chess E-Magazine January/February - 2012 Table of Contents Editorial~ “My Move” 4 contents Feature~ Chess and Canada 5 Article~ Bill Wall’s Top 10 Software Programs 9 INTERACTIVE CONTENT ________________ Feature~ The Incomparable Kasparov 10 • Click on title in Table of Contents Article~ Chess Variants 17 to move directly to Unorthodox Chess Variations page. • Click on “White Feature~ Proof Games 21 Knight Review” on the top of each page to return to ARTICLE~ The Immortal Game 22 Table of Contents. Anderssen Vrs. Kieseritzky • Click on red type to continue to next page ARTICLE~ News Around the World 24 • Click on ads to go to their websites BOOK REVIEW~ Kasparov on Kasparov Pt. 1 25 • Click on email to Pt.One, 1973-1985 open up email program Feature~ Chess Gambits 26 • Click up URLs to go to websites. ANNOTATED GAME~ Bareev Vs. Kasparov 30 COMMENTARY~ “Ask Bill” 31 White Knight Review January/February 2012 White Knight Review January/February 2012 Feature My Move Editorial - Jerry Wall [email protected] Well it has been over a year now since we started this publication. It is not easy putting together a 32 page magazine on chess White Knight every couple of months but it certainly has been rewarding (maybe not so Review much financially but then that really never was Chess E-Magazine the goal). -

Chess for Dummies‰

01_584049 ffirs.qxd 7/29/05 9:19 PM Page iii Chess FOR DUMmIES‰ 2ND EDITION by James Eade 01_584049 ffirs.qxd 7/29/05 9:19 PM Page ii 01_584049 ffirs.qxd 7/29/05 9:19 PM Page i Chess FOR DUMmIES‰ 2ND EDITION 01_584049 ffirs.qxd 7/29/05 9:19 PM Page ii 01_584049 ffirs.qxd 7/29/05 9:19 PM Page iii Chess FOR DUMmIES‰ 2ND EDITION by James Eade 01_584049 ffirs.qxd 7/29/05 9:19 PM Page iv Chess For Dummies®, 2nd Edition Published by Wiley Publishing, Inc. 111 River St. Hoboken, NJ 07030-5774 www.wiley.com Copyright © 2005 by Wiley Publishing, Inc., Indianapolis, Indiana Published simultaneously in Canada No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, scanning, or otherwise, except as permit- ted under Sections 107 or 108 of the 1976 United States Copyright Act, without either the prior written permission of the Publisher, or authorization through payment of the appropriate per-copy fee to the Copyright Clearance Center, 222 Rosewood Drive, Danvers, MA 01923, 978-750-8400, fax 978-646-8600. Requests to the Publisher for permission should be addressed to the Legal Department, Wiley Publishing, Inc., 10475 Crosspoint Blvd., Indianapolis, IN 46256, 317-572-3447, fax 317-572-4355, or online at http://www.wiley.com/go/permissions. Trademarks: Wiley, the Wiley Publishing logo, For Dummies, the Dummies Man logo, A Reference for the Rest of Us!, The Dummies Way, Dummies Daily, The Fun and Easy Way, Dummies.com, and related trade dress are trademarks or registered trademarks of John Wiley & Sons, Inc., and/or its affiliates in the United States and other countries, and may not be used without written permission. -

I Make This Pledge to You Alone, the Castle Walls Protect Our Back That I Shall Serve Your Royal Throne

AMERA M. ANDERSEN Battlefield of Life “I make this pledge to you alone, The castle walls protect our back that I shall serve your royal throne. and Bishops plan for their attack; My silver sword, I gladly wield. a master plan that is concealed. Squares eight times eight the battlefield. Squares eight times eight the battlefield. With knights upon their mighty steed For chess is but a game of life the front line pawns have vowed to bleed and I your Queen, a loving wife and neither Queen shall ever yield. shall guard my liege and raise my shield Squares eight times eight the battlefield. Squares eight time eight the battlefield.” Apathy Checkmate I set my moves up strategically, enemy kings are taken easily Knights move four spaces, in place of bishops east of me Communicate with pawns on a telepathic frequency Smash knights with mics in militant mental fights, it seems to be An everlasting battle on the 64-block geometric metal battlefield The sword of my rook, will shatter your feeble battle shield I witness a bishop that’ll wield his mystic sword And slaughter every player who inhabits my chessboard Knight to Queen’s three, I slice through MCs Seize the rook’s towers and the bishop’s ministries VISWANATHAN ANAND “Confidence is very important—even pretending to be confident. If you make a mistake but do not let your opponent see what you are thinking, then he may overlook the mistake.” Public Enemy Rebel Without A Pause No matter what the name we’re all the same Pieces in one big chess game GERALD ABRAHAMS “One way of looking at chess development is to regard it as a fight for freedom. -

Application of Chess Theory Free

FREE APPLICATION OF CHESS THEORY PDF Efim Geller,K.P. Neat | 270 pages | 01 Jan 1995 | EVERYMAN CHESS | 9781857440676 | English | London, United Kingdom Application of Chess Theory - Geller – Chess House The game of chess is commonly divided into three phases: the openingApplication of Chess Theoryand endgame. Those who write about chess theorywho are often also eminent players, are referred to as "theorists" or "theoreticians". The development of theory in all of these areas has been assisted by the vast literature on the game. Inpreeminent chess historian H. Murray wrote in his page magnum opus A History of Chess that, "The game possesses a literature which in contents probably exceeds that of all other games combined. Wood estimated that the number had increased to about 20, No one knows how many have been printed White Collection [10] at the Cleveland Public Librarycontains over 32, chess books and serials, including over 6, bound volumes of chess periodicals. The earliest printed work on chess theory whose date can be established with some exactitude is Repeticion de Amores y Arte de Ajedrez by the Spaniard Luis Ramirez de Lucenapublished c. Fifteen years Application of Chess Theory Lucena's book, Portuguese apothecary Pedro Damiano published the book Questo libro e da imparare giocare a scachi et de la partiti in Rome. It includes analysis of the Queen's Gambit Application of Chess Theory, showing what happens when Black tries to keep the gambit pawn with Nf3 f6? These books and later ones discuss games played with various openings, opening traps, and the best way for both sides to play. -

Chess Openings

Chess Openings PDF generated using the open source mwlib toolkit. See http://code.pediapress.com/ for more information. PDF generated at: Tue, 10 Jun 2014 09:50:30 UTC Contents Articles Overview 1 Chess opening 1 e4 Openings 25 King's Pawn Game 25 Open Game 29 Semi-Open Game 32 e4 Openings – King's Knight Openings 36 King's Knight Opening 36 Ruy Lopez 38 Ruy Lopez, Exchange Variation 57 Italian Game 60 Hungarian Defense 63 Two Knights Defense 65 Fried Liver Attack 71 Giuoco Piano 73 Evans Gambit 78 Italian Gambit 82 Irish Gambit 83 Jerome Gambit 85 Blackburne Shilling Gambit 88 Scotch Game 90 Ponziani Opening 96 Inverted Hungarian Opening 102 Konstantinopolsky Opening 104 Three Knights Opening 105 Four Knights Game 107 Halloween Gambit 111 Philidor Defence 115 Elephant Gambit 119 Damiano Defence 122 Greco Defence 125 Gunderam Defense 127 Latvian Gambit 129 Rousseau Gambit 133 Petrov's Defence 136 e4 Openings – Sicilian Defence 140 Sicilian Defence 140 Sicilian Defence, Alapin Variation 159 Sicilian Defence, Dragon Variation 163 Sicilian Defence, Accelerated Dragon 169 Sicilian, Dragon, Yugoslav attack, 9.Bc4 172 Sicilian Defence, Najdorf Variation 175 Sicilian Defence, Scheveningen Variation 181 Chekhover Sicilian 185 Wing Gambit 187 Smith-Morra Gambit 189 e4 Openings – Other variations 192 Bishop's Opening 192 Portuguese Opening 198 King's Gambit 200 Fischer Defense 206 Falkbeer Countergambit 208 Rice Gambit 210 Center Game 212 Danish Gambit 214 Lopez Opening 218 Napoleon Opening 219 Parham Attack 221 Vienna Game 224 Frankenstein-Dracula Variation 228 Alapin's Opening 231 French Defence 232 Caro-Kann Defence 245 Pirc Defence 256 Pirc Defence, Austrian Attack 261 Balogh Defense 263 Scandinavian Defense 265 Nimzowitsch Defence 269 Alekhine's Defence 271 Modern Defense 279 Monkey's Bum 282 Owen's Defence 285 St. -

Aron Nimzowitsch My System & Chess Praxis

Aron Nimzowitsch My System & Chess Praxis Translated by Robert Sherwood New In Chess 2016 Contents Translator’s Preface............................................... 9 My System Foreword..................................................... 13 Part I – The Elements . 15 Chapter 1 The Center and Development...............................16 1. By development is to be under stood the strategic advance of the troops to the frontier line ..............................16 2. A pawn move must not in and of itself be regarded as a develo ping move but should be seen simply as an aid to develop ment ........................................16 3. The lead in development as the ideal to be sought ..........18 4. Exchanging with resulting gain of tempo.................18 5. Liquidation, with subsequent development or a subsequent liberation ..........................................20 6. The center and the furious rage to demobilize it ...........23 7. On pawn hunting in the opening ......................28 Chapter 2 Open Files .............................................31 1. Introduction and general remarks.......................31 2. The origin (genesis) of the open file ....................32 3. The ideal (ultimate purpose) of every operation along a file ..34 4. The possible obstacles in the way of a file operation ........35 5. The ‘restricted’ advance along one file for the purpose of relin quishing that file for another one, or the indirect utilization of a file. 38 6. The outpost .......................................39 Chapter 3 The Seventh and Eighth Ranks ..............................44 1. Introduction and general remarks. .44 2. The convergent and the revo lutionary attack upon the 7th rank. .44 3. The five special cases on the seventh rank . .47 Chapter 4 The Passed Pawn ........................................75 1. By way of orientation ...............................75 2. The blockade of passed pawns .........................77 3. -

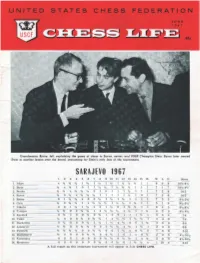

Sarajevo 1967 ° "' 1 '"

Grondmaster ayme, lefl, explafntnq the qallle 01 d»eu to 80"011, c.nter, and USSR Champion Stein, Byrne later floated SteIn 10 anOfher leuon o"er the board. accountmq tor Sleln's only lou 01 lhe lournamenl, SARAJEVO 1967 I 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 A 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 W L D !: ~~::: :::::::::::::::::::::.:.... .::: :' .' ...: . ~ ~~, ---.-~;.-.::~;--:~;-"~,==~: =~~f. =~"tl =j~~=;~t="ii"'\'----;.~:;:--;"-;-·I - ::- -;:===-;~'----;~'---";:""~=- 10 ~ .4- ~ 3. tknko , If.! Y.i: % 0 I 0 1 1 I ~ I \ _ ;-1 _~'~ ,;--;;-, - \1)-5 x 1h 'h ':-l - '--'' 1 I I 1 'h I 0 I ,';-,,'c-- -:';-_-- 1().5_ °1 '""' 1h x 0 0 n 1 n I ¥, I 1 1 I ,..' .....;:3_ ~ 9Ik.5 ~ h 1 x I,i h ~ 1 n h I I,i 1;.--:1_ _ 5 1 9 9h . ~~ ° "1 h 1 I,i x 0 I 'h 0 1 "':"''-''''7----:-1 t 6" 5'- - 8'7 .6% o o lit liz 1 x 1,1: .., .., 1 "':t I t ¥l -.' , 2 ~ 81.1 f1lh 1 0 0 n 0 If. :< 0 0 1 J I n _ -;-I _ ';--;-6_ ,_ _ ,.. - 11 Duc1n tcin .. .. .... ... n ~ ~ ~ ~ : ~ "~'- : : ~ ~ ~ --,~,,-:~:-~ ----.-~ :: ~! 12. Ja.noS('vic .... ... ... ... .. ~_-;";... _~ ~ _Ifl "1 ;;:0'--;,;..0 _ 0,,-:"':-"''7--;;:''--''''' 1 ~"''-.;.I _ _.;:-' _ ;!i 8 f.. 9 13. Pict%.Sch ................................... \o!t Vr 'tit;. _ ";. ,-~O:- 0 n 'fl 0 0 . __1 'h x 0 1:'.1 0 1 6 --;8- - - 5- 10 14. Bogdanuvic .. .................. Y.t 0 0 0 0 lit Yt 0 0 Yt 1 0 I x 0 h 2 8 5 _ _ " "1.100" :~ : ~:~;:~. -

Chess Review

MARCH 1968 • MEDIEVAL MANIKINS • 65 CENTS vI . Subscription Rat. •• ONE YEAR $7.S0 • . II ~ ~ • , .. •, ~ .. -- e 789 PAGES: 7'/'1 by 9 inches. clothbound 221 diagrams 493 ideo variations 1704 practical variations 463 supplementary variations 3894 notes to all variations and 439 COMPLETE GAMES! BY I. A . HOROWITZ in collaboration with Former World Champion, Dr, Max Euwe, Ernest Gruenfeld, Hans Kmoch, and many other noted authorities This Jatest and immense work, the mo~t exhaustive of i!~ kind, e:x · plains in encyclopedic detail the fine points of all openings. It carries the reader well into the middle game, evaluates the prospects there and often gives complete exemplary games so that he is not teft hanging in mid.position with the query : What bappens now? A logical sequence binds the continuity in each opening. Firsl come the moves with footnotes leading to the key position. Then fol· BIBLIOPHILES! low perlinenl observations, illustrated by "Idea Variations." Finally, Glossy paper, handsome print. Practical and Supplementary Variations, well annotated, exemplify the effective possibilities. Each line is appraised : or spacious poging and a ll the +, - = . The large format-71/2 x 9 inches- is designed for ease of rcad· other appurtenances of exquis· ing and playing. It eliminates much tiresome shuffling of pages ite book-making combine to between the principal lines and the respective comments. Clear, make this the handsomest of legible type, a wide margin for inserting notes and variation·identify· ing diagrams are other plus features. chess books! In addition to all else, fhi s book contains 439 complete ga mes- a golden trea.mry in itself! ORDER FROM CHESS REVIEW 1- --------- - - ------- --- - -- - --- -I I Please send me Chess Openings: Theory and Practice at $12.50 I I Narne • • • • • • • • • • .