THE GRAND CHESSBOARD American Primacy and Its Geostrategic Imperatives

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Combinatorics on the Chessboard

Combinatorics on the Chessboard Interactive game: 1. On regular chessboard a rook is placed on a1 (bottom-left corner). Players A and B take alternating turns by moving the rook upwards or to the right by any distance (no left or down movements allowed). Player A makes the rst move, and the winner is whoever rst reaches h8 (top-right corner). Is there a winning strategy for any of the players? Solution: Player B has a winning strategy by keeping the rook on the diagonal. Knight problems based on invariance principle: A knight on a chessboard has a property that it moves by alternating through black and white squares: if it is on a white square, then after 1 move it will land on a black square, and vice versa. Sometimes this is called the chameleon property of the knight. This is related to invariance principle, and can be used in problems, such as: 2. A knight starts randomly moving from a1, and after n moves returns to a1. Prove that n is even. Solution: Note that a1 is a black square. Based on the chameleon property the knight will be on a white square after odd number of moves, and on a black square after even number of moves. Therefore, it can return to a1 only after even number of moves. 3. Is it possible to move a knight from a1 to h8 by visiting each square on the chessboard exactly once? Solution: Since there are 64 squares on the board, a knight would need 63 moves to get from a1 to h8 by visiting each square exactly once. -

A Package to Print Chessboards

chessboard: A package to print chessboards Ulrike Fischer November 1, 2020 Contents 1 Changes 1 2 Introduction 2 2.1 Bugs and errors.....................................3 2.2 Requirements......................................4 2.3 Installation........................................4 2.4 Robustness: using \chessboard in moving arguments..............4 2.5 Setting the options...................................5 2.6 Saving optionlists....................................7 2.7 Naming the board....................................8 2.8 Naming areas of the board...............................8 2.9 FEN: Forsyth-Edwards Notation...........................9 2.10 The main parts of the board..............................9 3 Setting the contents of the board 10 3.1 The maximum number of fields........................... 10 1 3.2 Filling with the package skak ............................. 11 3.3 Clearing......................................... 12 3.4 Adding single pieces.................................. 12 3.5 Adding FEN-positions................................. 13 3.6 Saving positions..................................... 15 3.7 Getting the positions of pieces............................ 16 3.8 Using saved and stored games............................ 17 3.9 Restoring the running game.............................. 17 3.10 Changing the input language............................. 18 4 The look of the board 19 4.1 Units for lengths..................................... 19 4.2 Some words about box sizes.............................. 19 4.3 Margins......................................... -

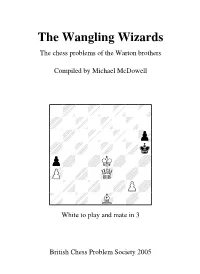

The Wangling Wizards the Chess Problems of the Warton Brothers

The Wangling Wizards The chess problems of the Warton brothers Compiled by Michael McDowell ½ û White to play and mate in 3 British Chess Problem Society 2005 The Wangling Wizards Introduction Tom and Joe Warton were two of the most popular British chess problem composers of the twentieth century. They were often compared to the American "Puzzle King" Sam Loyd because they rarely composed problems illustrating formal themes, instead directing their energies towards hoodwinking the solver. Piquant keys and well-concealed manoeuvres formed the basis of a style that became known as "Wartonesque" and earned the brothers the nickname "the Wangling Wizards". Thomas Joseph Warton was born on 18 th July 1885 at South Mimms, Hertfordshire, and Joseph John Warton on 22 nd September 1900 at Notting Hill, London. Another brother, Edwin, also composed problems, and there may have been a fourth composing Warton, as a two-mover appeared in the August 1916 issue of the Chess Amateur under the name G. F. Warton. After a brief flourish Edwin abandoned composition, although as late as 1946 he published a problem in Chess . Tom and Joe began composing around 1913. After Tom’s early retirement from the Metropolitan Police Force they churned out problems by the hundred, both individually and as a duo, their total output having been estimated at over 2600 problems. Tom died on 23rd May 1955. Joe continued to compose, and in the 1960s published a number of joints with Jim Cresswell, problem editor of the Busmen's Chess Review , who shared his liking for mutates. Many pleasing works appeared in the BCR under their amusing pseudonym "Wartocress". -

53Rd WORLD CONGRESS of CHESS COMPOSITION Crete, Greece, 16-23 October 2010

53rd WORLD CONGRESS OF CHESS COMPOSITION Crete, Greece, 16-23 October 2010 53rd World Congress of Chess Composition 34th World Chess Solving Championship Crete, Greece, 16–23 October 2010 Congress Programme Sat 16.10 Sun 17.10 Mon 18.10 Tue 19.10 Wed 20.10 Thu 21.10 Fri 22.10 Sat 23.10 ICCU Open WCSC WCSC Excursion Registration Closing Morning Solving 1st day 2nd day and Free time Session 09.30 09.30 09.30 free time 09.30 ICCU ICCU ICCU ICCU Opening Sub- Prize Giving Afternoon Session Session Elections Session committees 14.00 15.00 15.00 17.00 Arrival 14.00 Departure Captains' meeting Open Quick Open 18.00 Solving Solving Closing Lectures Fairy Evening "Machine Show Banquet 20.30 Solving Quick Gun" 21.00 19.30 20.30 Composing 21.00 20.30 WCCC 2010 website: http://www.chessfed.gr/wccc2010 CONGRESS PARTICIPANTS Ilham Aliev Azerbaijan Stephen Rothwell Germany Araz Almammadov Azerbaijan Rainer Staudte Germany Ramil Javadov Azerbaijan Axel Steinbrink Germany Agshin Masimov Azerbaijan Boris Tummes Germany Lutfiyar Rustamov Azerbaijan Arno Zude Germany Aleksandr Bulavka Belarus Paul Bancroft Great Britain Liubou Sihnevich Belarus Fiona Crow Great Britain Mikalai Sihnevich Belarus Stewart Crow Great Britain Viktor Zaitsev Belarus David Friedgood Great Britain Eddy van Beers Belgium Isabel Hardie Great Britain Marcel van Herck Belgium Sally Lewis Great Britain Andy Ooms Belgium Tony Lewis Great Britain Luc Palmans Belgium Michael McDowell Great Britain Ward Stoffelen Belgium Colin McNab Great Britain Fadil Abdurahmanović Bosnia-Hercegovina Jonathan -

Geostrategy and Canadian Defence: from C.P. Stacey to a Twenty-First Century Arctic Threat Assessment

Journal of Military and Strategic VOLUME 20, ISSUE 1 Studies Geostrategy and Canadian Defence: From C.P. Stacey to a Twenty-First Century Arctic Threat Assessment Ryan Dean and P. Whitney Lackenbauer1 “If some countries have too much history, we have too much geography.” -- Prime Minister William Lyon Mackenzie King, 1936 Geostrategy is the study of the importance of geography to strategy and military operations. Strategist Bernard Loo explains that “it is the influence of geography on tactical and operational elements of the strategic calculus that underpins, albeit subliminally, strategic calculations about the feasibility of the use of military force because the geographical conditions will influence policy-makers’ and strategic 1 An early version of some sections of this article appeared as “Geostrategical Approaches,” a research report for Defence Research and Development Canada (DRDC) project on the Assessment of Threats Against Canada submitted in 2015. We are grateful to the coordinators of that project, as well as to reviewers who provided feedback that has strengthened this article. Final research and writing was completed pursuant to a Department of National Defence MINDS Collaborative Network grant supporting the North American and Arctic Defence and Security Network (NAADSN). ©Centre of Military and Strategic Studies, 2019 ISSN : 1488-559X JOURNAL OF MILITARY AND STRATEGIC STUDIES planners’ perceptions of strategic vulnerabilities or opportunities.”2 By extension, the geographical size and location of a country are key determinants -

ECSP Report 3

FOREWORD by P.J . Simmons, Editor ust over two years ago, then U.S. Permanent Representative to the United Nations Madeleine K. Albright Jargued that “environmental degradation is not simply an irritation, but a real threat to our national security.” As Secretary of State, Ms. Albright has already indicated that she intends to build upon the pathbreaking initia- tive of her predecessor, Warren Christopher, to make environmental issues “part of the mainstream of American foreign policy.” On Earth Day 1997, Albright issued the State Department’s first annual report on “Environmen- tal Diplomacy: the Environment and U.S. Foreign Policy.” In it, Secretary Albright asserted that global environ- mental damage “threatens the health of the American people and the future of our economy” and that “environ- mental problems are often at the heart of the political and economic challenges we face around the world.” Noting that “we have moved beyond the Cold War definition of the United States’ strategic interests,” Vice President Gore argued the Department’s report “documents an important turning point in U.S. foreign policy— a change the President and I strongly support.” Similar sentiments expressed by officials in the United States and abroad indicate the growing interest in the interactions among environmental degradation, natural re- source scarcities, population dynamics, national interests and security.* The breadth and diversity of views and initiatives represented in this issue of the Environmental Change and Security Project Report reflect the advances in research, contentious political debates and expanding parameters of this important field of academic and policy inquiry. As a neutral forum for discussion, the Report includes articles asserting strong connections between environment and security as well as more skeptical analyses. -

Шахматных Задач Chess Exercises Schachaufgaben

Всеволод Костров Vsevolod Kostrov Борис Белявский Boris Beliavsky 2000 Шахматных задач Chess exercises Schachaufgaben РЕШЕБНИК TACTICAL CHESS.. EXERCISES SCHACHUBUNGSBUCH Шахматные комбинации Chess combinations Kombinationen Часть 1-2 разряд Part 1700-2000 Elo 3 Teil 1-2 Klasse Русский шахматный дом/Russian Chess House Москва, 2013 В первых двух книжках этой серии мы вооружили вас мощными приёмами для успешного ведения шахматной борьбы. В вашем арсенале появились двойной удар, связка, завлечение и отвлечение. Новый «Решебник» обогатит вас более изысканным тактическим оружием. Не всегда до короля можно добраться, используя грубую силу. Попробуйте обхитрить партнёра с помощью плаща и кинжала. Маскируйтесь, как разведчик, и ведите себя, как опытный дипломат. Попробуйте найти слабое место в лагере противника и в нужный момент уничтожьте защиту и нанесите тонкий кинжальный удар. Кстати, чужие фигуры могут стать союзниками. Умелыми манёврами привлеките фигуры противника к их королю, пускай они его заблокируют так, чтобы ему, бедному, было не вздохнуть, и в этот момент нанесите решающий удар. Неприятно, когда все фигуры вашего противника взаимодействуют между собой. Может, стоить вбить клин в их порядки – перекрыть их прочной шахматной дверью. А так ли страшна атака противника на ваши укрепления? Стоит ли уходить в глухую оборону? Всегда ищите контрудар. Тонкий промежуточный укол изменит ход борьбы. Не сгрудились ли ваши фигуры на небольшом пространстве, не мешают ли они друг другу добраться до короля противника? Решите, кому всё же идти на штурм королевской крепости, и освободите пространство фигуре для атаки. Короля всегда надо защищать в первую очередь. Используйте это обстоятельство и совершите открытое нападение на него и другие фигуры. И тогда жернова вашей «мельницы» перемелют всё вражеское войско. -

Chapter I Geostrategic and Geopolitical Considerations

Geostrategic and geopolitical Chapter I considerations regarding energy Francisco José Berenguer Hernández Abstract This chapter analyses the peace and conflict aspects of the concept of “energy security” its importance in the strategic architecture of the major nations, as well as the main geopolitical factors of the current energy panorama. Key words Energy Security, National Strategies, Energy Interests, Geopolitics of Energy. 45 Francisco José Berenguer Hernández Some considerations about the “energy security” concept Concept The concept of energy security has been present in publications for a cer- tain number of years, including the press and non-trade media, but it is apparently a recent one, or at least one that has not enjoyed the popular- ity of others such as road, workplace, social or even air security. However, it has taken on such importance nowadays that it deserves a specific section in the highest-level strategic documents of practically all of the nations in our environment, as will be seen in a later section. This is somewhat different from the form of security of other sectors that include the following in more generic terms: “well-being and progress of society”, “ensuring the life and prosperity of citizens” and other simi- lar expressions, with the exception of economic security. The latter, as a consequence of the long and deep recession that numerous nations, in- cluding Spain, have been suffering, has strongly emerged in more recent strategic thinking. Consequently, it is worth wondering the reason for this relevance and leading role of energy security in the concerns of the high- est authorities and institutions of the nations. -

001-386 Vilner 14-10-19.Indd

Yakov Vilner First Ukrainian Chess Champion and First USSR Chess Composition Champion A World Champion's Favorite Composers Sergei Tkachenko Yakov Vilner, First Ukrainian Chess Champion and First USSR Chess Composition Champion: A World Champion's Favorite Composers Author: Sergei Tkachenko Translated from the Russian by Ilan Rubin Chess editors: Grigory Baranov and Anastasia Travkina Typesetting by Andrei Elkov (www.elkov.ru) © LLC Elk and Ruby Publishing House, 2019. All rights reserved Part I originally published in Russia in 2016 © Sergei Tkachenko and Andrei Elkov. All rights reserved Part II originally published in Ukraine in 2013 © Sergei Tkachenko and VMV. All rights reserved Cover page by Vitaly Bashilov Follow us on Twitter: @ilan_ruby www.elkandruby.com ISBN 978-5-6040710-6-9 CONTENTS Index of Games and Fragments ...............................................................4 Yakov Vilner’s key achievements ............................................................. 6 PART I – LIFE AND GAMES Introduction: The crystal of the immortal human spirit ............................ 8 All grown-ups were children once ...........................................................11 His first steps in chess .............................................................................19 The best player in Odessa ........................................................................26 Chess life in Odessa reawakens ................................................................33 The key is to begin! .................................................................................39 -

Contact: Amanda Weinberg Phone: 610-565-1023 E-Mail: [email protected]

Contact: Amanda Weinberg Phone: 610-565-1023 E-mail: [email protected] THE STRONGEST-EVER CHESS TOURNAMENT IN PENNSYLVANIA RICHARD ARONOW FOUNDATION INVITATIONAL COMPLETED THREE PLAYERS OBTAIN INTERNATIONAL MASTER NORMS A suspense-filled evening on Sunday, July 21, 2002 saw the completion of the Richard Aronow Foundation Invitational Tournament, which was held at the Franklin Mercantile Chess Club in Center City, Philadelphia, from July 12 to July 21. The final game completed was the decisive one, in which the first prizewinner, Grandmaster Gennady Zaitchik of Georgia, competed with Grandmaster Yevgeny Najer of Russia for the top prize of $1000. Najer and National Master Yury Lapshun tied for second and third place, and won $250 each. International Master Luis Chiong of the Philippines won a $150 “brilliancy” prize for his performance against International Master Oladapo Adu of Nigeria, by decision of the Tournament Committee. National Masters Yevgeny Gershov and Bryan Smith split a $150 “best endgame” prize for their match, by decision of President Richard Costigan of the Franklin Mercantile Chess Club. Three participants: National Masters Mikhail Belorusov and Stanislav Kriventsov of Pennsylvania, and Yury Lapshun of New York, obtained norms which must precede a nomination for the title of International Master by the international chess organization, the Federation International des Echecs (“FIDE”). Kriventsov and Lapshun each obtained their third and final requisite norm, and will likely be nominated as International Masters when FIDE convenes in October. This tournament was organized to serve two purposes: 1. to promote high-level, invitational chess tournaments in the U.S., and 2. to publicize the Richard Aronow Foundation and the need for research on autism. -

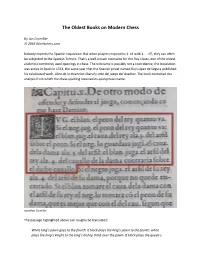

The Oldest Books on Modern Chess

The Oldest Books on Modern Chess By Jon Crumiller © 2016 Worldchess.com Nobody expects the Spanish Inquisition. But when players respond to 1. e4 with 1. … e5, they can often be subjected to the Spanish Torture. That’s a well-known nickname for the Ruy López, one of the oldest and most commonly used openings in chess. The nickname is possibly not a coincidence; the Inquisition was active in Spain in 1561, the same year that the Spanish priest named Ruy López de Segura published his celebrated work, Libro de la Invencion liberal y Arte del juego del Axedrez. The book contained the analysis from which the chess opening received its eponymous name. Jonathan Crumiller The passage highlighted above can roughly be translated: White king’s pawn goes to the fourth. If black plays the king’s pawn to the fourth: white plays the king’s knight to the king’s bishop third, over the pawn. If black plays the queen’s knight to queen’s bishop third: white plays the king’s bishop to the fourth square of the contrary queen’s knight, opposed to that knight. Or in our modern chess language: 1. e4, e5 2. Nf3, Nc6 3. Bb5. Jonathan Crumiller On the right is how the Ruy López opening would have looked four centuries ago with a standard chess set and board in Spain. This Spanish chess set is one of my oldest complete sets (along with a companion wooden set of the same era). Jonathan Crumiller Here is the Ruy López as seen with that companion set displayed on a Spanish chessboard, also from the 1600’s. -

No. 123 - (Vol.VIH)

No. 123 - (Vol.VIH) January 1997 Editorial Board editors John Roycrqfttf New Way Road, London, England NW9 6PL Edvande Gevel Binnen de Veste 36, 3811 PH Amersfoort, The Netherlands Spotlight-column: J. Heck, Neuer Weg 110, D-47803 Krefeld, Germany Opinions-column: A. Pallier, La Mouziniere, 85190 La Genetouze, France Treasurer: J. de Boer, Zevenenderdrffi 40, 1251 RC Laren, The Netherlands EDITORIAL achievement, recorded only in a scientific journal, "The chess study is close to the chess game was not widely noticed. It was left to the dis- because both study and game obey the same coveries by Ken Thompson of Bell Laboratories rules." This has long been an argument used to in New Jersey, beginning in 1983, to put the boot persuade players to look at studies. Most players m. prefer studies to problems anyway, and readily Aside from a few upsets to endgame theory, the give the affinity with the game as the reason for set of 'total information' 5-raan endgame their preference. Your editor has fought a long databases that Thompson generated over the next battle to maintain the literal truth of that ar- decade demonstrated that several other endings gument. It was one of several motivations in might require well over 50 moves to win. These writing the final chapter of Test Tube Chess discoveries arrived an the scene too fast for FIDE (1972), in which the Laws are separated into to cope with by listing exceptions - which was the BMR (Board+Men+Rules) elements, and G first expedient. Then in 1991 Lewis Stiller and (Game) elements, with studies firmly identified Noam Elkies using a Connection Machine with the BMR realm and not in the G realm.