“Jewish Problem”: Othering the Jews and Homogenizing Europe

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Music for the People: the Folk Music Revival

MUSIC FOR THE PEOPLE: THE FOLK MUSIC REVIVAL AND AMERICAN IDENTITY, 1930-1970 By Rachel Clare Donaldson Dissertation Submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School of Vanderbilt University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in History May, 2011 Nashville, Tennessee Approved Professor Gary Gerstle Professor Sarah Igo Professor David Carlton Professor Larry Isaac Professor Ronald D. Cohen Copyright© 2011 by Rachel Clare Donaldson All Rights Reserved For Mary, Laura, Gertrude, Elizabeth And Domenica ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would not have been able to complete this dissertation had not been for the support of many people. Historians David Carlton, Thomas Schwartz, William Caferro, and Yoshikuni Igarashi have helped me to grow academically since my first year of graduate school. From the beginning of my research through the final edits, Katherine Crawford and Sarah Igo have provided constant intellectual and professional support. Gary Gerstle has guided every stage of this project; the time and effort he devoted to reading and editing numerous drafts and his encouragement has made the project what it is today. Through his work and friendship, Ronald Cohen has been an inspiration. The intellectual and emotional help that he provided over dinners, phone calls, and email exchanges have been invaluable. I greatly appreciate Larry Isaac and Holly McCammon for their help with the sociological work in this project. I also thank Jane Anderson, Brenda Hummel, and Heidi Welch for all their help and patience over the years. I thank the staffs at the Smithsonian Center for Folklife and Cultural Heritage, the Kentucky Library and Museum, the Archives at the University of Indiana, and the American Folklife Center at the Library of Congress (particularly Todd Harvey) for their research assistance. -

Moses and Frances Asch Collection, 1926-1986

Moses and Frances Asch Collection, 1926-1986 Cecilia Peterson, Greg Adams, Jeff Place, Stephanie Smith, Meghan Mullins, Clara Hines, Bianca Couture 2014 Ralph Rinzler Folklife Archives and Collections Smithsonian Center for Folklife and Cultural Heritage 600 Maryland Ave SW Washington, D.C. [email protected] https://www.folklife.si.edu/archive/ Table of Contents Collection Overview ........................................................................................................ 1 Administrative Information .............................................................................................. 1 Arrangement note............................................................................................................ 3 Biographical/Historical note.............................................................................................. 2 Scope and Contents........................................................................................................ 2 Names and Subjects ...................................................................................................... 3 Container Listing ............................................................................................................. 5 Series 1: Correspondence, 1942-1987 (bulk 1947-1987)........................................ 5 Series 2: Folkways Production, 1946-1987 (bulk 1950-1983).............................. 152 Series 3: Business Records, 1940-1987.............................................................. 477 Series 4: Woody Guthrie -

Pete Seeger and Intellectual Property Law

Teaching The Hudson River Valley Review Teaching About “Teaspoon Brigade: Pete Seeger, Folk Music, and International Property Law” –Steve Garabedian Lesson Plan Introduction: Students will use the Hudson River Valley Review (HRVR) Article: “Teaspoon Brigade: Pete Seeger, Folk Music, and International Property Law” as a model for an exemplary research paper (PDF of the full article is included in this PDF). Lesson activities will scaffold student’s understanding of the article’s theme as well as the article’s construction. This lesson concludes with an individual research paper constructed by the students using the information and resources understood in this lesson sequence. Each activity below can be adapted according to the student’s needs and abilities. Suggested Grade Level: 11th grade US History: Regents level and AP level, 12th grade Participation in Government: Regents level and AP level. Objective: Students will be able to: Read and comprehend the provided text. Analyze primary documents, literary style. Explain and describe the theme of the article: “Teaspoon Brigade: Pete Seeger, Folk Music, and International Property Law” in a comprehensive summary. After completing these activities students will be able to recognize effective writing styles. Standards Addressed: Students will: Use important ideas, social and cultural values, beliefs, and traditions from New York State and United States history illustrate the connections and interactions of people and events across time and from a variety of perspectives. Develop and test hypotheses about important events, eras, or issues in United States history, setting clear and valid criteria for judging the importance and significance of these events, eras, or issues. -

Smithsonian Folkways Recordings: a Question of Balance

Smithsonian Folkways Recordings: A Question of Balance D. A. Sonnebom How does a small record label, operating within a large museum setting, balance its educational mission's imperatives against economic need, a pair of priorities inherently in conflict? The following is a personal and reflexive view, affected in some measure by oral transmissions received from institutional elders but based always on my own experience. When I was a child, my home was filled with music from all over the world, including many releases from Folkways Records. Individually and as a collection, the music opened windows of my imagination and initiated a sense of curiosity and wonder about the experience and perception of others. The material ignited a musical passion that has proved lasting. I have served as Assistant Director of Smithsonian Folkways Recordings since 1998 and thus have had opportunity to live with the tensions of its "mission vs. operational needs" polarity, both to ask and try to answer the question on a daily basis. I offer this essay to readers in hopes that it may help demythologize and demystify the process whereby recordings of community-based traditions are promulgated from the setting of the United States national museum and into the increasingly globalized marketplace. The attacks on the World Trade Center and the Pentagon in September 2001 exacerbated an economic contraction already in progress in the U.S. and produced a precipitous drop in recording sales during that year's last few months. The North American music industry continued depressed in 2002, with sales down on average more than ten percent as compared to the prior year. -

This Machine Kills Fascists" : the Public Pedagogy of the American Folk Singer

University of Louisville ThinkIR: The University of Louisville's Institutional Repository Electronic Theses and Dissertations 8-2016 "This machine kills fascists" : the public pedagogy of the American folk singer. Harley Ferris University of Louisville Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.library.louisville.edu/etd Part of the Rhetoric Commons Recommended Citation Ferris, Harley, ""This machine kills fascists" : the public pedagogy of the American folk singer." (2016). Electronic Theses and Dissertations. Paper 2485. https://doi.org/10.18297/etd/2485 This Doctoral Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by ThinkIR: The University of Louisville's Institutional Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ThinkIR: The University of Louisville's Institutional Repository. This title appears here courtesy of the author, who has retained all other copyrights. For more information, please contact [email protected]. “THIS MACHINE KILLS FASCISTS”: THE PUBLIC PEDAGOGY OF THE AMERICAN FOLK SINGER By Harley Ferris B.A., Jacksonville University, 2010 M.A., University of Louisville, 2012 A Dissertation Submitted to the Faculty of the College of Arts and Sciences of the University of Louisville in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in English/Rhetoric and Composition Department of English University of Louisville Louisville, KY August 2016 “THIS MACHINE KILLS FASCISTS”: THE PUBLIC PEDAGOGY OF THE AMERICAN -

The Brothers Nazaroff 1

THE HAPPY PRINCE NAZAROVYE! A GREETING FROM THE BROTHERS NAZARISHE GREETINGS TO ALL. Thank you for acquiring this most joyous of musical tributes to our beloved lost uncle, the “Prince.” Three score years ago, the venerable Moses Asch released Nathan “Prince” Nazaroff’s 10” record, Jewish Freilach Songs (FW 6809). It has since proved to be a guiding light in the search for a missing link between our post-modern Babylo- nian exile and the lost Atlantis of Yiddish “Middle-Europe.” The “Prince” came to our American shores in 1914, as the old world crumbled. One hundred years later, we, the amalgamated and wind-strewn spiritual nephews of the great Nazaroff, have gathered to honor our lost Tumler Extraordinaire, a true troubadour of the vanished Yiddish street. Leaving our homes in New York, Berlin, Budapest, Moscow, and France, we began recording these songs in an astrological library in Michigan and finished up in an attic in Berlin. We were armed with a smattering of languages, several instruments, a bird whistle from Istanbul, and the indispensable liner notes to the original Folkways album (available for download from Smithsonian Folkways’ website—we encourage any listener to this recording to obtain a copy). We have tried to stay true to Nazaroff’s neshome (soul), khokhme (wit), style, and sense of music. The “Prince” was truly a big-time performer. By keeping his music alive, we hope to bring him into an even bigger time: the future. So let’s now celebrate the discordant, obscure, jubilant, ecstatic legacy of our Happy “Prince.” NAZAROVYE! THE HAPPY PRINCE THE BROTHERS NAZAROFF 1 THE HAPPY PRINCE 1. -

Anarchist Modernism and Yiddish Literature

i “Any Minute Now the World’s Overflowing Its Border”: Anarchist Modernism and Yiddish Literature by Anna Elena Torres A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Joint Doctor of Philosophy with the Graduate Theological Union in Jewish Studies and the Designated Emphasis in Women, Gender and Sexuality in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Professor Chana Kronfeld, Chair Professor Naomi Seidman Professor Nathaniel Deutsch Professor Juana María Rodríguez Summer 2016 ii “Any Minute Now the World’s Overflowing Its Border”: Anarchist Modernism and Yiddish Literature Copyright © 2016 by Anna Elena Torres 1 Abstract “Any Minute Now the World’s Overflowing Its Border”: Anarchist Modernism and Yiddish Literature by Anna Elena Torres Joint Doctor of Philosophy with the Graduate Theological Union in Jewish Studies and the Designated Emphasis in Women, Gender and Sexuality University of California, Berkeley Professor Chana Kronfeld, Chair “Any Minute Now the World’s Overflowing Its Border”: Anarchist Modernism and Yiddish Literature examines the intertwined worlds of Yiddish modernist writing and anarchist politics and culture. Bringing together original historical research on the radical press and close readings of Yiddish avant-garde poetry by Moyshe-Leyb Halpern, Peretz Markish, Yankev Glatshteyn, and others, I show that the development of anarchist modernism was both a transnational literary trend and a complex worldview. My research draws from hitherto unread material in international archives to document the world of the Yiddish anarchist press and assess the scope of its literary influence. The dissertation’s theoretical framework is informed by diaspora studies, gender studies, and translation theory, to which I introduce anarchist diasporism as a new term. -

May 1965 Sing Out, Songs from Berkeley, Irwin Silber

IN THIS ISSUE SONGS INSTRUMENTAL TECHNIQUES OF AMERICAN FOLK GUITAR - An instruction book on Carter Plcldng' and Fingerplcking; including examples from Elizabeth Cotten, There But for Fortune 5 Mississippi John Hurt, Rev. Gary Davis, Dave Van Ronk, Hick's Farewell 14 etc, Forty solos fUll y written out in musIc and tablature. Little Sally Racket 15 $2.95 plus 25~ handllng. Traditional stringed Instruments, Long Black Veil 16 P.O. Box 1106, Laguna Beach, CaUl. THE FOLK SONG MAGAZINE Man with the Microphone 21 SEND FOR YOUR FREE CATALOG on Epic hand crafted 'The Verdant Braes of Skreen 22 ~:~~~d~e Epic Company, 5658 S. Foz Circle, Littleton, VOL. 15, NO. 2 W ith International Section MAY 1965 75~ The Commonwealth of Toil 26 -An I Want Is Union 27 FREE BEAUTIFUL SONG. All music-lovers send names, Links on the Chain 32 ~~g~ ~ses . Nordyke, 6000-21 Sunset, Hollywood, call!. JOHNNY CASH MUDDY WATERS Get Up and Go 34 Long Thumb 35 DffiE CTORY OF COFFEE HOUSE S Across the Country ••• The Hell-Bound Train 38 updated edition covers 150 coffeehouses: addresses, des criptions, detaUs on entertaInment policies. $1 .00. TaUs Beans in My Ears 45 man Press, Boz 469, Armonk, N. Y. (Year's subscription Cannily, Cannily 46 to supplements $1.00 additional). ARTICLES FOLK MUSIC SUPPLIE S: Records , books, guitars, banjos, accessories; all available by mall. Write tor information. Denver Folklore Center, 608 East 17th Ave., Denver 3, News and Notes 2 Colo. R & B (Tony Glover) 6 Son~s from Berkeley NAKADE GUITARS - ClaSSical, Flamenco, Requinta. -

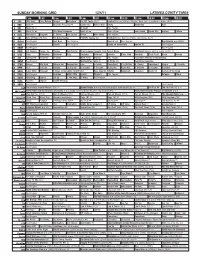

Sunday Morning Grid 12/4/11 Latimes.Com/Tv Times

SUNDAY MORNING GRID 12/4/11 LATIMES.COM/TV TIMES 7 am 7:30 8 am 8:30 9 am 9:30 10 am 10:30 11 am 11:30 12 pm 12:30 2 CBS CBS News Face/Nation Danger Horseland The NFL Today (N) Å Football Raiders at Miami Dolphins. From Sun Life Stadium in Miami. (N) Å 4 NBC News Å Meet the Press (N) Å Conference Willa’s Wild Skiing Swimming Golf 5 CW News (N) Å In Touch Paid Program 7 ABC News (N) Å This Week-Amanpour News (N) Å News (N) Å Jack Hanna Ocean Mys. Explore Culture 9 KCAL Tomorrow’s Kingdom K. Shook Joel Osteen Prince Mike Webb Paid Program 11 FOX Hour of Power (N) (TVG) Fox News Sunday FOX NFL Sunday (N) Football Denver Broncos at Minnesota Vikings. (N) Å 13 MyNet Paid Program Best Buys Paid Program Best of L.A. Paid Program Bee Season ›› (2005) 18 KSCI Paid Program Church Paid Program Hecho en Guatemala Iranian TV Paid Program 22 KWHY Paid Program Paid Program 24 KVCR Sid Science Curios -ity Thomas Bob Builder Classic Gospel Special: Tent Revival Home Prohibition Groups push to outlaw alcohol. Å 28 KCET Cons. Wubbulous Busytown Peep Pancakes Pufnstuf Lidsville Place, Own Roadtrip Chefs Field Pépin Venetia 30 ION Turning Pnt. Discovery In Touch Mark Jeske Beyond Paid Program Inspiration Ministry Campmeeting 34 KMEX Paid Program Muchachitas Como Tu Al Punto (N) República Deportiva 40 KTBN Rhema Win Walk Miracle-You Redemption Love In Touch PowerPoint It Is Written B. Conley From Heart King Is J. -

Nomination Form International Memory of the World Register

Nomination form International Memory of the World Register MOSES AND FRANCES ASCH COLLECTION Center for Folklife and Cultural Heritage, Smithsonian Institution ID Code [2014-66] 1.0 Summary With the mission of representing an “encyclopedia of sound,” the Moses and Frances Asch Collection (1926-1987) serves as a unique testament to the breadth and depth of the twentieth-century human experience. The collection features material of both famous and lesser known writers, poets, documentarians, ethnographers, and grass roots musicians from around the world. The series Folkways Records includes a diversity of documentary, audio, visual, and business materials from Folkways Records, one of the most influential record labels of the twentieth century. American folk icon Woody Guthrie recorded on Folkways, and the collection includes selections of his correspondence, lyrics, drawings, and writings in the series The Woody Guthrie Papers. The collection notably contains correspondence with numerous influential individuals of the twentieth century, such as John Cage, Langston Hughes, Margaret Walker, Lead Belly, Pete Seeger, Peggy Seeger, Ewan MacColl, Alan Lomax, Kenneth Patchen, and others. It also includes ethnographic field notes and field photographs by Béla Bartók, Henry Cowell, Sidney Robertson Cowell, Harold Courlander, and Sam Charters. Moses Asch’s business papers from his various record labels, including but not limited to Folkways Records, offers insight to the history of the recording industry and music business. The collection prominently features audio recordings of rare and extinct documentary sounds, both man-made and natural, such as steam engines, extinct and endangered animal species, minority languages, and occupational soundscapes of years past. Moses Asch hired prominent artists and graphic designers to create album cover art for commercial recordings. -

Anthology of American Folk Music”--Harry Smith, Editor (1952) Added to the National Registry: 2005 Essay by Ian Nagoski (Guest Post)*

“Anthology of American Folk Music”--Harry Smith, editor (1952) Added to the National Registry: 2005 Essay by Ian Nagoski (guest post)* Original album package “An Anthology of American Folk Music” is a compilation of 84 vernacular performances from commercial 78rpm discs originally issued during the years 1927-32. It was produced by Harry Smith and issued as three two-LP sets by Moses Asch’s Folkways Records in 1952. It was kept in print from the time of its original release for three decades before it was reissued on compact disc to critical heraldry by Smithsonian/ Folkways in 1997. During the 1950s and 60s, the collection deeply influenced a generation of musicians and listeners and has helped to define the idea of “American Music” in the popular imagination, due in large part to the peculiar sensibilities of its compiler, Harry Smith. Smith was born Mary 29, 1923 in Portland, Oregon, and raised in small towns in the northwest by parents with humdrum jobs and involvements with both Lummi Indians (on this mother’s side) and Masonry and Spiritualism (on his father’s). By his teens, he had attended exclusive Indian ceremonies and bought recordings by African-American performers, including Memphis Minnie, Rev. F.W. McGee, Tommy McClennan, and Yank Rachell, which lit the fuse of a life-long fireworks display of obsessive collecting of records that were “exotic in relation to what was considered the world culture of high class music,” as he put it in a 1960s interview with John Cohen. After a year and half studying anthology at the University of Seattle, Smith relocated to Berkeley, California, ca. -

Werner Huber, Sandra Mayer, Julia Novak (Eds.)

Werner Huber, Sandra Mayer, Julia Novak (eds.) IRELAND IN/AND EUROPE: CROSS-CURRENTS AND EXCHANGES Irish Studies in Europe Edited by Werner Huber, Catherine Maignant, Hedwig Schwall Volume 4 Werner Huber, Sandra Mayer, Julia Novak (eds.) IRELAND IN/AND EUROPE: CROSS-CURRENTS AND EXCHANGES Wissenschaftlicher Verlag Trier Ireland in/and Europe: Cross-Currents and Exchanges / Werner Huber, Sandra Mayer, Julia Novak (eds.). - Trier: WVT Wissenschaftlicher Verlag Trier, 2012 (Irish Studies in Europe; vol. 4) ISBN 978-3-86821-421-5 Umschlaggestaltung: Brigitta Disseldorf © WVT Wissenschaftlicher Verlag Trier, 2012 ISBN 978-3-86821-421-5 Alle Rechte vorbehalten Nachdruck oder Vervielfältigung nur mit ausdrücklicher Genehmigung des Verlags WVT Wissenschaftlicher Verlag Trier Bergstraße 27, 54295 Trier Postfach 4005, 54230 Trier Tel.: (0651) 41503, Fax: 41504 Internet: http://www.wvttrier.de E-Mail: [email protected] CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS 9 Werner Huber (Vienna), Sandra Mayer (Vienna), Julia Novak (Vienna) INTRODUCTION 11 Seamus Heaney (Dublin) MOSSBAWN VIA MANTUA: IRELAND IN/AND EUROPE: CROSS-CURRENTS AND EXCHANGES 19 Barbara Freitag (Dublin) HY BRASIL: CARTOGRAPHIC ERROR, CELTIC ELYSIUM, OR THE NEW JERUSALEM? EARLY LITERARY REPRESENTATIONS OF THE IMAGINARY BRASIL ISLAND 29 Eglantina Remport (Budapest) “MY CHANGE OF CHARACTER”: ROUSSEAUISME AND MARIA EDGEWORTH’S ENNUI 41 Gabriella Vö (Pécs) THE RISE OF THE HUNGARIAN DANDY: OSCAR WILDE’S CONTRIBUTION TO THE EXPERIENCE OF MODERNITY IN EARLY-TWENTIETH-CENTURY HUNGARY 51 Sandra Andrea O’Connell (Dublin) PUBLISHED IN PARIS: SAMUEL BECKETT, GEORGE REAVEY, AND THE EUROPA PRESS 65 Ute Anna Mittermaier (Vienna) FRANCO’S SPAIN: A DUBIOUS REFUGE FOR THE POETS OF THE ‘IRISH BEAT GENERATION’ IN THE 1960S 79 Sarah Heinz (Mannheim) FROM UTOPIA TO HETEROTOPIA: IRISH WRITERS NARRATING THE SPANISH CIVIL WAR 93 Michael G.