Differences in Grape Phylloxera-Related Grapevine Root

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Xylella Fastidiosa – What Do We Know and Are We Ready

Xylella fastidiosa: What do we know and are we ready? Suzanne McLoughlin, Vinehealth Australia. Xylella is a major threat due to its multiple hosts Suzanne McLoughlin, Vinehealth Australia’s (more than 350 plant species, many of which Technical Manager, analyses the grape and wine do not show symptoms), its multiple vectors community’s preparedness and knowledge about and its continued global spread. The pathogen Xylella fastidiosa, which is known to the industry causes clogging of plant xylem vessels, resulting as Pierce’s disease. This article first appeared in Australian and New Zealand Grapegrower and in water stress-like symptoms to distal parts of Winemaker Magazine, June 2017. the grapevine, with vine death in 1-2 years post infection (Figure 44). The bacterium is primarily Introduction transmitted in the gut of sapsucking insects and Xylella fastidiosa is a gram-negative, rod-shaped the disease cannot occur without a vector. bacterium known to cause Pierce’s disease in viticulture. Xylella fastidiosa was the subject of an While Xylella fastidiosa is known as Pierce’s international symposium held in Brisbane in May disease in grapevines, it is known as many other 2017, organised by the Department of Agriculture names in other host plants. It is inherently difficult and Water Resources (DAWR). A broad range of to control and there are no known treatments to international experts shared their knowledge and cure diseased plants. experience on Xylella with Australian federal and Xylella fastidiosa has been reported on various state government biosecurity personnel, as well host crops, either symptomatic or asymptomatic, as a small number of invited industry participants. -

Current Breeding Efforts in Salt‐And Drought-Tolerant Rootstocks –

12/12/2017 Current Breeding Efforts in Salt‐and Drought-Tolerant Rootstocks – Andy Walker ([email protected]) California Grape Rootstock Improvement Commission / California Grape Rootstock Research Foundation CDFA NT, FT, GV Improvement Advisory Board California Table Grape Commission American Vineyard Foundation E&J Gallo Winery Louise Rossi Endowed Chair in Viticulture Rootstock Breeding Objectives • Develop better forms of drought and salinity tolerance • Combine these tolerances with broad nematode resistance and high levels of phylloxera resistance • Develop better fanleaf degeneration tolerant rootstocks • Develop rootstocks with “Red Leaf” virus tolerance 1 12/12/2017 V. riparia Missouri River V. rupestris Jack Fork River, MO 2 12/12/2017 V. berlandieri Fredericksburg, TX Which rootstock to choose? • riparia based – shallow roots, water sensitive, low vigor, early maturity: – 5C, 101-14, 16161C (3309C) • rupestris based – broadly distributed roots, relatively drought tolerant, moderate to high vigor, midseason maturity: – St. George, 1103P, AXR#1 (3309C) 3 12/12/2017 Which rootstock to choose? • berlandieri based – deeper roots, drought tolerant, higher vigor, delayed maturity: – 110R, 140Ru (420A, 5BB) • champinii based – deeper roots, drought tolerant, salt tolerance, but variable in hybrids – Dog Ridge, Ramsey (Salt Creek) – Freedom, Harmony, GRNs • Site trumps all… soil depth, rainfall, soil texture, water table V. monticola V. candicans 4 12/12/2017 CP‐SSR LN33 1613-59 V. riparia x V. rupestris Couderc 1613 14 markers 22 haplotypes Harmony Freedom V. berlandieri x V. riparia Couderc 1616 Ramsey Vitis rupestris cv Witchita refuge V. berlandieri x V. rupestris 157-11 (Couderc) 3306 (Couderc) V. berlandieri x V. vinifera 3309 (Couderc) Vitis riparia cv. -

Propagating Grapevines

EHT-116 4/19 Propagating Grapevines Justin Scheiner and Andrew King Department of Horticultural Sciences, The Texas A&M University System Plant propagation is the process of creating new Dormant Hardwood Cuttings plants. Asexual propagation is the development Dormant canes are one-year-old wood that con- of a new plant from a piece of another plant. The tain buds. These canes are the tissue of choice for result is a plant that is genetically identical to propagating grapes. Most of the wood removed the mother or stock plant. Sexual propagation is during dormant winter pruning can be used to the development of a new plant from a seed with generate new vines (Fig. 1). Dormant canes con- genetic material from two plants. This process tain fully developed buds with rudimentary shoots results in offspring that are genetically different comprised of leaf and cluster primordia and stored from the mother plant and from one another. energy. The carbohydrates contained in the wood This difference is due to genetic recombination will fuel the growth of roots and shoots until the during meiosis. Although grapes can be readily new grapevine has enough functioning leaves to grown from seed, all commercial grape cultivars support itself. are propagated asexually. This is the only way to maintain the exact characteristics of a specific grape cultivar. The mother plant’s characteristics must be maintained to use the cultivar name for marketing purposes, such as on a wine label. Some of the grape cultivars grown today were developed hundreds of years ago and have been preserved through asexual propagation. -

Evaluating Resistance to Grape Phylloxera in Vitis Species with an in Vitro Dual Culture Assay WLADYSLAWA GRZEGORCZYK ~ and M

Evaluating Resistance to Grape Phylloxera in Vitis Species with an in vitro Dual Culture Assay WLADYSLAWA GRZEGORCZYK ~ and M. ANDREW WALKER 2. Forty-one accessions of 12 Vitis L. and Muscadinia Small species were evaluated for resistance to grape phylloxera (Daktulosphaira vitifoliae Fitch) using an in vitro dual culture system. The performance of the species tested in this study was consistent with previously published studies with whole plants and helps confirm the utility of in vitro dual culture for the study of grape/phylloxera interactions. This in vitro system provides rapid results (8 wk) and the ability to observe the phylloxera/grape interaction without interference from other factors. This system also provides an evaluation that overemphasizes susceptibility, thus providing more confidence in the resistance responses of a given species or accession. Among the unusual responses were the susceptibility of V. riparia Michx. DVIT 1411; susceptibility within V. berlandieri Planch.; relatively wide ranging responses in V. rupestris Scheele; and the lack of feeding on the roots of V. califomica Benth., in contrast to the severe foliar feeding damage that occurred on this species. Vitis califomica #11 and V. girdiana Munson DVIT 1379 were unusual because phylloxera on them had the shortest generation times. Such accessions might be used to examine how grape hosts influence phylloxera behavior. Very strong resistance was found within V. aestivalisMichx. DVIT 7109 and 7110; I/. berlandieric9031; V. cinereaEngelm; I/. riparia (excluding DVIT 1411 ); V. rupestris DVIT 1418 and 1419; and M. rotundifolia Small. These species and accessions seem to possess enough resistance to enable their use in breeding with minimal concern about phylloxera susceptibility. -

Matching Grape Varieties to Sites Are Hybrid Varieties Right for Oklahoma?

Matching Grape Varieties to Sites Are hybrid varieties right for Oklahoma? Bruce Bordelon Purdue University Wine Grape Team 2014 Oklahoma Grape Growers Workshop 2006 survey of grape varieties in Oklahoma: Vinifera 80%. Hybrids 15% American 7% Muscadines 1% Profiles and Challenges…continued… • V. vinifera cultivars are the most widely grown in Oklahoma…; however, observation and research has shown most European cultivars to be highly susceptible to cold damage. • More research needs to be conducted to elicit where European cultivars will do best in Oklahoma. • French-American hybrids are good alternatives due to their better cold tolerance, but have not been embraced by Oklahoma grape growers... Reasons for this bias likely include hybrid cultivars being perceived as lower quality than European cultivars, lack of knowledge of available hybrid cultivars, personal preference, and misinformation. Profiles and Challenges…continued… • The unpredictable continental climate of Oklahoma is one of the foremost obstacles for potential grape growers. • It is essential that appropriate site selection be done prior to planting. • Many locations in Oklahoma are unsuitable for most grapes, including hybrids and American grapes. • Growing grapes in Oklahoma is a risky endeavor and minimization of potential loss by consideration of cultivar and environmental interactions is paramount to ensure long-term success. • There are areas where some European cultivars may succeed. • Many hybrid and American grapes are better suited for most areas of Oklahoma than -

Phylogenetic Analysis of Vitaceae Based on Plastid Sequence Data

PHYLOGENETIC ANALYSIS OF VITACEAE BASED ON PLASTID SEQUENCE DATA by PAUL NAUDE Dissertation submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree MAGISTER SCIENTAE in BOTANY in the FACULTY OF SCIENCE at the UNIVERSITY OF JOHANNESBURG SUPERVISOR: DR. M. VAN DER BANK December 2005 I declare that this dissertation has been composed by myself and the work contained within, unless otherwise stated, is my own Paul Naude (December 2005) TABLE OF CONTENTS Table of Contents Abstract iii Index of Figures iv Index of Tables vii Author Abbreviations viii Acknowledgements ix CHAPTER 1 GENERAL INTRODUCTION 1 1.1 Vitaceae 1 1.2 Genera of Vitaceae 6 1.2.1 Vitis 6 1.2.2 Cayratia 7 1.2.3 Cissus 8 1.2.4 Cyphostemma 9 1.2.5 Clematocissus 9 1.2.6 Ampelopsis 10 1.2.7 Ampelocissus 11 1.2.8 Parthenocissus 11 1.2.9 Rhoicissus 12 1.2.10 Tetrastigma 13 1.3 The genus Leea 13 1.4 Previous taxonomic studies on Vitaceae 14 1.5 Main objectives 18 CHAPTER 2 MATERIALS AND METHODS 21 2.1 DNA extraction and purification 21 2.2 Primer trail 21 2.3 PCR amplification 21 2.4 Cycle sequencing 22 2.5 Sequence alignment 22 2.6 Sequencing analysis 23 TABLE OF CONTENTS CHAPTER 3 RESULTS 32 3.1 Results from primer trail 32 3.2 Statistical results 32 3.3 Plastid region results 34 3.3.1 rpL 16 34 3.3.2 accD-psa1 34 3.3.3 rbcL 34 3.3.4 trnL-F 34 3.3.5 Combined data 34 CHAPTER 4 DISCUSSION AND CONCLUSIONS 42 4.1 Molecular evolution 42 4.2 Morphological characters 42 4.3 Previous taxonomic studies 45 4.4 Conclusions 46 CHAPTER 5 REFERENCES 48 APPENDIX STATISTICAL ANALYSIS OF DATA 59 ii ABSTRACT Five plastid regions as source for phylogenetic information were used to investigate the relationships among ten genera of Vitaceae. -

Rootstocks As a Management Strategy for Adverse Vineyard Conditions

FACT SHEET 14 MODULE 14 Rootstocks as a management strategy for adverse vineyard conditions AUTHOR: Catherine Cox - Phylloxera and Grape Industry Board of South Australia These updates are supported by the Australian Government through the Irrigation Industries Workshop Programme - Wine Industry Project in partnership with the Department of Agriculture, Fisheries and Forestry and the Grape and Wine Research and Development Corporation. waterandvine.gwrdc.com.au Rootstocks as a management strategy for adverse vineyard conditions Introduction 2 Understanding different rootstock This Fact Sheet consolidates current knowledge around the key characteristics rootstocks used in Australian Viticulture in terms of tolerance to V. riparia x V. rupestris drought, salinity and lime. These rootstocks offer low-moderate vigour to the scion, and in The aim of this module is to briefly summarise the pros and cons certain situations hasten ripening. They do not tolerate drought of each rootstock and showcase the existing industry resources conditions. These characteristics make them particularly suited that can be used to aid in the selection of rootstocks in the key to cool climate viticulture. These rootstocks perform best on growing regions within the Murray Darling Basin. soils that dry out slowly and have moderate-high water holding For more information and training contact your local Innovator’s capacities. They impart low vigour to the scion and hence are Network member or go to http://waterandvine.gwrdc.com.au. suitable to high fertility sites and growing conditions. V. berlandieri x V. riparia 1 Introduction to rootstocks These rootstocks offer moderate-high vigour to the scion Grapevine rootstocks are derived from American Vitis species that depending on the soil type. -

Vitis Riparia

OPTIMISATION OF SUSTAINABILITY OF GRAPEVINE VARIETIES BY SELECTING ROOTSTOCK VARIETIES UNDER DIFFERENT ENVIRONMENTAL CONDITIONS AND CREATING NEW ROOTSTOCK VARIETIES Joachim Schmid, Frank Manty, Ernst Rühl Geisenheim University Institut for Grapevine Breeding Joachim Schmid Entrance to UNESCO world heritage site Rüdesheim Joachim Schmid 16.01.2015Titel der 2 Präsentation Joachim Schmid • Rootstock breeding and the use of rootstocks is the result and the answer to the introduction of phylloxera • All present rootstocks are hybrids of wild Vitis species with specific characteristics Titel der Präsentation Joachim Schmid 16.01.2015 4 VITIS RIPARIA Advantages Phylloxera tolerant very high frost resistance (<‐40°C) early bud break, early ripening good rooting ability Disadvantages susceptible to drought Low lime tolerance Joachim Schmid 5 VITIS BERLANDIERI Advantages Phylloxera tolerant high lime tolerance salt tolerant medium to good drought tolerance Disadvantages poor rooting ability late ripening Joachim Schmid 6 VITIS RUPESTRIS Advantages Phylloxera tolerant good rooting ability average lime tolerance good drought tolerance – but susceptible on shallow soils Disadvantages low vigour (in the motherblock) early bud break Joachim Schmid 7 VITIS CINEREA Advantages Phylloxera resistant good drought tolerance Disadvantages poor rooting ability low lime tolerance late bud break Joachim Schmid 8 ROOTSTOCK BREEDERS IN HUNGARY, AUSRTRIA AND GERMANY Sigmund TELEKI (1854‐1910) & Franz KOBER (1864‐1943) Vitis berlandieri x Vitis riparia • Teleki 8 -

Rôles Du Porte-Greffe Et Du Greffon Dans La Réponse À La Disponibilité En Phosphore Chez La Vigne

Rôles du porte-greffe et du greffon dans la réponse àla disponibilité en phosphore chez la Vigne Antoine Gautier To cite this version: Antoine Gautier. Rôles du porte-greffe et du greffon dans la réponse à la disponibilité en phosphore chez la Vigne. Biologie végétale. Université de Bordeaux, 2018. Français. NNT : 2018BORD0257. tel-02388497 HAL Id: tel-02388497 https://tel.archives-ouvertes.fr/tel-02388497 Submitted on 2 Dec 2019 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. THÈSE PRÉSENTÉE POUR OBTENIR LE GRADE DE DOCTEUR DE L’UNIVERSITÉ DE BORDEAUX École doctorale des Sciences de la Vie et de la Santé Spécialité : Biologie Végétale Par Antoine GAUTIER Rôles du porte-greffe et du greffon dans la réponse à la disponibilité en phosphore chez la Vigne Sous la direction de : Sarah Jane COOKSON Soutenue le 30 novembre 2018 Membres du jury : Mme GENY, Laurence Professeur, Université de Bordeaux Présidente M. DOERNER, Peter Directeur de Recherche, University of Edinburgh Rapporteur M. PERET, Benjamin Chargé de Recherche, CNRS Montpellier Rapporteur M. HINSINGER, Philippe Directeur de Recherche, INRA Montpellier Examinateur Mme OLLAT, Nathalie Ingénieure de Recherche, INRA Bordeaux Invitée Mme COOKSON, Sarah J. -

Temperature Is an Important Environmental Factor Affecting Growth and Mycotoxin Production by Molds

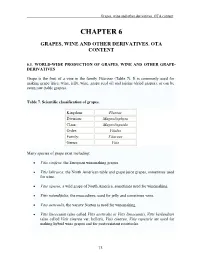

Grapes, wine and other derivatives. OTA content. CHAPTER 6 GRAPES, WINE AND OTHER DERIVATIVES. OTA CONTENT 6.1. WORLD-WIDE PRODUCTION OF GRAPES, WINE AND OTHER GRAPE- DERIVATIVES Grape is the fruit of a vine in the family Vitaceae (Table 7). It is commonly used for making grape juice, wine, jelly, wine, grape seed oil and raisins (dried grapes), or can be eaten raw (table grapes). Table 7. Scientific classification of grapes. Kingdom: Plantae Division: Magnoliophyta Class: Magnoliopsida Order: Vitales Family: Vitaceae Genus: Vitis Many species of grape exist including: • Vitis vinifera, the European winemaking grapes. • Vitis labrusca, the North American table and grape juice grapes, sometimes used for wine. • Vitis riparia, a wild grape of North America, sometimes used for winemaking. • Vitis rotundifolia, the muscadines, used for jelly and sometimes wine. • Vitis aestivalis, the variety Norton is used for winemaking. • Vitis lincecumii (also called Vitis aestivalis or Vitis lincecumii), Vitis berlandieri (also called Vitis cinerea var. helleri), Vitis cinerea, Vitis rupestris are used for making hybrid wine grapes and for pest-resistant rootstocks. 73 CHAPTER 6 . The main reason for the use of most V. vinifera varieties in wine production is their high sugar content, which after fermentation, produce a wine with an alcohol content of 10 % or slightly higher. Grape varieties of V. vinifera have a great variation of composition. Skin pigment colours vary from greenish yellow to russet, pink, red, reddish violet or blue-black. The colour of red wines comes from the skin, not the juice. The juice is normally colourless, though some varieties have a pink to red colour. -

GRAPE and WINE INDUSTRY SUBMISSION to the NATIONAL XYLELLA FASTIDIOSA ACTION PLAN 27Th December 2018

GRAPE AND WINE INDUSTRY SUBMISSION TO THE NATIONAL XYLELLA FASTIDIOSA ACTION PLAN 27th December 2018 Australia’s grape and wine industry welcomes the opportunity to provide comments to the National Xylella Fastidiosa Action Plan. As the signatory to the Emergency Plant Pest Response deed, and member of Plant Health Australia, Australian Vignerons (AV) is currently the organisation with national remit in addressing biosecurity issues in the wine industry. More recently the Winemakers’ Federation of Australia (WFA) has joined as a member of Plant Health Australia. As of 1st February 2019, AV and WFA will amalgamate to form a single industry peak body, Australian Grape and Wine. This submission has been written on behalf of the wine industry and has received input and endorsement from the following national and state-based organisations: • Australian Vignerons: peak industry body for winegrape growers across Australia; • Winemakers’ Federation of Australia: peak industry body for Australia’s Winemaker; and • Vinehealth Australia: SA statutory authority governed by the Phylloxera and Grape Industry Act 1995 to protect vineyards from pest and disease; The Australian Wine Research Institute also reviewed the submission. The Australia wine industry The Australian wine industry supports the economic, environmental and social fabric of 65 rural and regional wine regions across the country. It is the only agricultural industry that is quite so vertically integrated at the production and manufacturing enterprise level based in rural and regional Australia. Winemakers grow grapes, manufacture the wine, package, distribute, export and market their own product. A large grower community provides wineries a diverse supply base to meet product and market requirements. -

Modifications Induced by Rootstocks on Yield, Vigor and Nutritional

agronomy Article Modifications Induced by Rootstocks on Yield, Vigor and Nutritional Status on Vitis vinifera Cv Syrah under Hyper-Arid Conditions in Northern Chile Nicolás Verdugo-Vásquez 1 , Gastón Gutiérrez-Gamboa 2,* , Irina Díaz-Gálvez 3, Antonio Ibacache 4 and Andrés Zurita-Silva 1,* 1 Centro de Investigación Intihuasi, Instituto de Investigaciones Agropecuarias INIA, Colina San Joaquín s/n, La Serena 1700000, Chile; [email protected] 2 Escuela de Agronomía, Facultad de Ciencias, Universidad Mayor, Camino La Pirámide 5750, Huechuraba 8580000, Chile 3 Centro de Investigación Raihuén, Instituto de Investigaciones Agropecuarias INIA, Casilla 34, San Javier 3660000, Chile; [email protected] 4 Private Consultant, La Serena 1700000, Chile; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected] (G.G.-G.); [email protected] (A.Z.-S.) Abstract: Hyper-arid regions are characterized by extreme conditions for growing and lack of water (<100 mm annual rainfall average), where desertification renders human activities almost impossible. In addition to the use of irrigation, different viticultural strategies should be taken into account to face the adverse effects of these conditions in which rootstocks may play a crucial role. The research Citation: Verdugo-Vásquez, N.; aim was to evaluate the effects of the rootstock on yield, vigor, and petiole nutrient content in Syrah Gutiérrez-Gamboa, G.; Díaz-Gálvez, grapevines growing under hyper-arid conditions during five seasons and compare them to ungrafted I.; Ibacache, A.; Zurita-Silva, A. ones. St. George induced lower yield than 1103 Paulsen. Salt Creek induced higher plant growth Modifications Induced by Rootstocks on Yield, Vigor and Nutritional Status vigor and Cu petiole content than ungrafted vines in Syrah, which was correlated to P petiole content.