GRAPE and WINE INDUSTRY SUBMISSION to the NATIONAL XYLELLA FASTIDIOSA ACTION PLAN 27Th December 2018

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

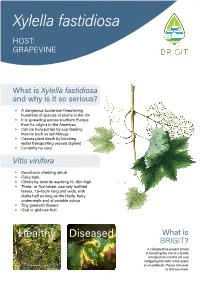

Xylella Fastidiosa HOST: GRAPEVINE

Xylella fastidiosa HOST: GRAPEVINE What is Xylella fastidiosa and why is it so serious? ◆ A dangerous bacterium threatening hundreds of species of plants in the UK ◆ It is spreading across southern Europe from its origins in the Americas ◆ Can be transported by sap-feeding insects such as spittlebugs ◆ Causes plant death by blocking water transporting vessels (xylem) ◆ Currently no cure Vitis vinifera ◆ Deciduous climbing shrub ◆ Flaky bark ◆ Climbs by tendrils reaching 15–18m high ◆ Three- or five-lobed, coarsely toothed leaves, 7.5–15cm long and wide, with stalks half as long as the blade, hairy underneath and of variable colour ◆ Tiny greenish flowers ◆ Oval or globose fruit Healthy Diseased What is BRIGIT? A collaborative project aimed at reducing the risk of a Xylella introduction into the UK and mitigating the risks in the event of an outbreak. Please turn over to find out more. What to look 1 out for 2 ◆ Marginal leaf scorch 1 ◆ Leaf chlorosis 2 ◆ Premature loss of leaves 3 ◆ Matchstick petioles 3 ◆ Irregular cane maturation (green islands in stems) 4 ◆ Fruit drying and wilting 5 ◆ Stunting of new shoots 5 ◆ Death of plant in 1–5 years Where is the plant from? 3 ◆ Plants sourced from infected countries are at a much higher risk of carrying the disease-causing bacterium Do not panic! 4 How long There are other reasons for disease symptoms to appear. Consider California. of University Montpellier; watercolour, RHS Lindley Collections; “healthy”, RHS / Tim Sandall; “diseased”, J. Clark, California 3 J. Clark & A.H. Purcell, University of California 4 J. Clark, University of California 5 ENSA, Images © 1 M. -

Xylella Fastidiosa – What Do We Know and Are We Ready

Xylella fastidiosa: What do we know and are we ready? Suzanne McLoughlin, Vinehealth Australia. Xylella is a major threat due to its multiple hosts Suzanne McLoughlin, Vinehealth Australia’s (more than 350 plant species, many of which Technical Manager, analyses the grape and wine do not show symptoms), its multiple vectors community’s preparedness and knowledge about and its continued global spread. The pathogen Xylella fastidiosa, which is known to the industry causes clogging of plant xylem vessels, resulting as Pierce’s disease. This article first appeared in Australian and New Zealand Grapegrower and in water stress-like symptoms to distal parts of Winemaker Magazine, June 2017. the grapevine, with vine death in 1-2 years post infection (Figure 44). The bacterium is primarily Introduction transmitted in the gut of sapsucking insects and Xylella fastidiosa is a gram-negative, rod-shaped the disease cannot occur without a vector. bacterium known to cause Pierce’s disease in viticulture. Xylella fastidiosa was the subject of an While Xylella fastidiosa is known as Pierce’s international symposium held in Brisbane in May disease in grapevines, it is known as many other 2017, organised by the Department of Agriculture names in other host plants. It is inherently difficult and Water Resources (DAWR). A broad range of to control and there are no known treatments to international experts shared their knowledge and cure diseased plants. experience on Xylella with Australian federal and Xylella fastidiosa has been reported on various state government biosecurity personnel, as well host crops, either symptomatic or asymptomatic, as a small number of invited industry participants. -

Citrus Blight and Other Diseases � of Recalcitrant Etiology

P1: FRK August 1, 2000 18:44 Annual Reviews AR107-09 Annu. Rev. Phytopathol. 2000. 38:181–205 Copyright c 2000 by Annual Reviews. All rights reserved CITRUS BLIGHT AND OTHER DISEASES OF RECALCITRANT ETIOLOGY KS Derrick and LW Timmer University of Florida, Institute of Food and Agricultural Sciences, Citrus Research and Education Center, Lake Alfred, Florida 33850-2299; e-mail: [email protected]fl.edu, [email protected]fl.edu Key Words citrus psorosis, citrus variegated chlorosis, lettuce big vein, peach tree short life, replant diseases ■ Abstract Several economically important diseases of unknown or recently de- termined cause are reviewed. Citrus blight (CB), first described over 100 years ago, was shown in 1984 to be transmitted by root-graft inoculations; the cause remains unknown and is controversial. Based on graft transmission, it is considered to be an infectious agent by some; others suggest that the cause of CB is abiotic. Citrus varie- gated chlorosis, although probably long present in Argentina, where it was considered to be a variant of CB, was identified as a specific disease and shown to be caused by a strain of Xylella fastidiosa after if reached epidemic levels in Brazil in 1987. Citrus psorosis, described in 1933 as the first virus disease of citrus, is perhaps one of the last to be characterized. In 1988, it was shown to be caused by a very unusual virus. The cause of lettuce big vein appears to be a viruslike agent that is transmitted by a soilborne fungus. Double-stranded RNAs were associated with the disease, suggesting it may be caused by an unidentified RNA virus. -

Propagating Grapevines

EHT-116 4/19 Propagating Grapevines Justin Scheiner and Andrew King Department of Horticultural Sciences, The Texas A&M University System Plant propagation is the process of creating new Dormant Hardwood Cuttings plants. Asexual propagation is the development Dormant canes are one-year-old wood that con- of a new plant from a piece of another plant. The tain buds. These canes are the tissue of choice for result is a plant that is genetically identical to propagating grapes. Most of the wood removed the mother or stock plant. Sexual propagation is during dormant winter pruning can be used to the development of a new plant from a seed with generate new vines (Fig. 1). Dormant canes con- genetic material from two plants. This process tain fully developed buds with rudimentary shoots results in offspring that are genetically different comprised of leaf and cluster primordia and stored from the mother plant and from one another. energy. The carbohydrates contained in the wood This difference is due to genetic recombination will fuel the growth of roots and shoots until the during meiosis. Although grapes can be readily new grapevine has enough functioning leaves to grown from seed, all commercial grape cultivars support itself. are propagated asexually. This is the only way to maintain the exact characteristics of a specific grape cultivar. The mother plant’s characteristics must be maintained to use the cultivar name for marketing purposes, such as on a wine label. Some of the grape cultivars grown today were developed hundreds of years ago and have been preserved through asexual propagation. -

Matching Grape Varieties to Sites Are Hybrid Varieties Right for Oklahoma?

Matching Grape Varieties to Sites Are hybrid varieties right for Oklahoma? Bruce Bordelon Purdue University Wine Grape Team 2014 Oklahoma Grape Growers Workshop 2006 survey of grape varieties in Oklahoma: Vinifera 80%. Hybrids 15% American 7% Muscadines 1% Profiles and Challenges…continued… • V. vinifera cultivars are the most widely grown in Oklahoma…; however, observation and research has shown most European cultivars to be highly susceptible to cold damage. • More research needs to be conducted to elicit where European cultivars will do best in Oklahoma. • French-American hybrids are good alternatives due to their better cold tolerance, but have not been embraced by Oklahoma grape growers... Reasons for this bias likely include hybrid cultivars being perceived as lower quality than European cultivars, lack of knowledge of available hybrid cultivars, personal preference, and misinformation. Profiles and Challenges…continued… • The unpredictable continental climate of Oklahoma is one of the foremost obstacles for potential grape growers. • It is essential that appropriate site selection be done prior to planting. • Many locations in Oklahoma are unsuitable for most grapes, including hybrids and American grapes. • Growing grapes in Oklahoma is a risky endeavor and minimization of potential loss by consideration of cultivar and environmental interactions is paramount to ensure long-term success. • There are areas where some European cultivars may succeed. • Many hybrid and American grapes are better suited for most areas of Oklahoma than -

Dual RNA Sequencing of Vitis Vinifera During Lasiodiplodia Theobromae Infection Unveils Host–Pathogen Interactions

International Journal of Molecular Sciences Article Dual RNA Sequencing of Vitis vinifera during Lasiodiplodia theobromae Infection Unveils Host–Pathogen Interactions Micael F. M. Gonçalves 1 , Rui B. Nunes 1, Laurentijn Tilleman 2 , Yves Van de Peer 3,4,5 , Dieter Deforce 2, Filip Van Nieuwerburgh 2, Ana C. Esteves 6 and Artur Alves 1,* 1 Department of Biology, CESAM, University of Aveiro, 3810-193 Aveiro, Portugal; [email protected] (M.F.M.G.); [email protected] (R.B.N.) 2 Laboratory of Pharmaceutical Biotechnology, Campus Heymans, Ottergemsesteenweg 460, B-9000 Ghent, Belgium; [email protected] (L.T.); [email protected] (D.D.); [email protected] (F.V.N.) 3 Department of Plant Biotechnology and Bioinformatics, Ghent University, 9052 Ghent, Belgium; [email protected] 4 Center for Plant Systems Biology, VIB, 9052 Ghent, Belgium 5 Department of Biochemistry, Genetics and Microbiology, University of Pretoria, Pretoria 0028, South Africa 6 Faculty of Dental Medicine, Center for Interdisciplinary Research in Health (CIIS), Universidade Católica Portuguesa, Estrada da Circunvalação, 3504-505 Viseu, Portugal; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +351-234-370-766 Received: 28 October 2019; Accepted: 29 November 2019; Published: 3 December 2019 Abstract: Lasiodiplodia theobromae is one of the most aggressive agents of the grapevine trunk disease Botryosphaeria dieback. Through a dual RNA-sequencing approach, this study aimed to give a broader perspective on the infection strategy deployed by L. theobromae, while understanding grapevine response. Approximately 0.05% and 90% of the reads were mapped to the genomes of L. -

Differences in Grape Phylloxera-Related Grapevine Root

PLANT PATHOLOGY HORTSCIENCE 34(6):1108–1111. 1999. ing vineyards may result in reduced phyllox- era numbers and phylloxera-related damage. The purpose of this work was to determine Differences in Grape Phylloxera- whether differences in phylloxera populations or phylloxera-related damage could be attrib- related Grapevine Root Damage in uted to organic or conventional management Organically and Conventionally regimes. Materials and Methods Managed Vineyards in California Two types of long-term vineyard manage- ment regimes were compared, organic and D.W. Lotter, J. Granett, and A.D. Omer conventional. Organically managed vineyards Department of Entomology, University of California, One Shields Avenue, (OMV) chosen for study were certified by the Davis, CA 95616-8584 California Certified Organic Farmers program (Santa Cruz) and were characterized by the Additional index words. Vitis vinifera, Daktulosphaira vitifoliae, organic farming, sustain- use of cover crops and composts and no syn- able agriculture, soil suppressiveness, Trichoderma thetic fertilizers or pesticides. Vineyards that had been organically certified for at least 5 Abstract. Secondary infection of roots by fungal pathogens is a primary cause of vine years and were infested with phylloxera were damage in phylloxera-infested grapevines (Vitis vinifera L.). In summer and fall surveys selected for this study. The time threshold of 5 in 1997 and 1998, grapevine root samples were taken from organically (OMVs) and years of organic management was chosen based conventionally managed vineyards (CMVs), all of which were phylloxera-infested. In both on experiences of organic farmers, consult- years, root samples from OMVs showed significantly less root necrosis caused by fungal ants, and researchers indicating that the full pathogens than did samples from CMVs, averaging 9% in OMVs vs. -

Pierce's Disease Research Symposium Proceedings

Pierce’s Disease Control Program Symposium Proceedings 2004 Pierce’s Disease Research Symposium December 7 – 10, 2004 Coronado Island Marriott Resort Coronado, California California Department of Food & Agriculture Proceedings of the 2004 Pierce’s Disease Research Symposium December 7 – 10, 2004 Coronado Island Marriott Resort Coronado, California Organized by: California Department of Food and Agriculture Proceedings Compiled by: M. Athar Tariq, Stacie Oswalt, Peggy Blincoe, Amadou Ba, Terrance Lorick, and Tom Esser Cover Design: Peggy Blincoe Printer: Copeland Printing, Sacramento, CA Funds for Printing Provided by: CDFA Pierce’s Disease and Glassy-winged Sharpshooter Board To order additional copies of this publication, please contact: Pierce’s Disease Control Program California Department of Food and Agriculture 2014 Capitol Avenue, Suite 109 Telephone: (916) 322-2804 Fax: (916) 322-3924 http://www.cdfa.ca.gov/phpps/pdcp E-mail: [email protected] NOTE: The progress reports in this publication have not been subject to independent scientific review. The California Department of Food and Agriculture makes no warranty, expressed or implied, and assumes no legal liability for the information in this publication. The publication of the Proceedings by CDFA does not constitute a recommendation or endorsement of products mentioned. TABLE OF CONTENTS Section 1: Crop Biology and Disease Epidemiology Xylem Chemistry Mediation of Resistance to Pierce’s Disease Peter C. Andersen....................................................................................................................................................................... -

Improved ELISA Detection of Xylella Fastidiosa in Woody Plant Tissue Using Sap Extracted by a Pressure Chamber J

Improved ELISA detection of Xylella fastidiosa in woody plant tissue using sap extracted by a pressure chamber J. M. French 1, J. J. Randall2, R. J. Heerema1, S. F. Hanson2,N. P. Goldberg1. Department of Extension Plant Sciences1,New Mexico State University, Las Cruces, NM 88003; Department EPPWS2, New Mexico State University, Las Cruces, NM 88003 Abstract Chitalpa No. ELISA Result % PCR Culture Grape No ELISA Result % PCR Culture PB 50 + 80 + + Xylella fastidiosa is a xylem-limited, fastidious bacterium which causes scorch and dwarfing 1 + 8 + + diseases in many plant species. We recently reported X. fastidiosa in chitalpa, an ornamental 11 +/- 18 1 +/- 8 landscape tree. In evaluating chitalpa trees, we observed that some trees tested positive by PCR, 1 - 2 LV-2 11 - 84 but consistently tested negative or borderline using ELISA, which is preferred for ease of use and W1A 18 + 90 + - 2 + 16 + - cost effectiveness compared with PCR. This inconsistency may be due to significant within-plant 2 - 10 LV-3 11 - 84 and plant-to-plant variability in bacterial titer, thereby making detection using small amounts of tissue CB 17 + 24 + + 2 + 17 + - and ELISA more difficult. We evaluated the use of four extraction techniques, mortar and pestle, 3 +/- 4 1 +/- 8 - hammer, mini-bead beater, and pressure chamber, for their ability to extract X. fastidiosa from A 50 - 72 LV-4 9 - 75 chitalpa and grape, and compared the results from ELISA with those from PCR. For each extraction W2A 6 + 50 + + technique, except the pressure chamber, 0.3g of tissue was ground in 3 ml buffer. -

ISPM 27 Diagnostic Protocols for Regulated Pests DP 25: Xylella

This diagnostic protocol was adopted by the Standards Committee on behalf of the Commission on Phytosanitary Measures in August 2018. The annex is a prescriptive part of ISPM 27. ISPM 27 Diagnostic protocols for regulated pests DP 25: Xylella fastidiosa Adopted 2018; published 2018 CONTENTS 1. Pest Information ...............................................................................................................................3 2. Taxonomic Information ....................................................................................................................3 3. Detection ...........................................................................................................................................4 3.1 Symptoms ..........................................................................................................................4 3.1.1 Pierce’s disease of grapevines ...........................................................................................4 3.1.2 Citrus variegated chlorosis ................................................................................................5 3.1.3 Coffee leaf scorch .............................................................................................................5 3.1.4 Olive leaf scorching and quick decline .............................................................................5 3.1.5 Almond leaf scorch disease ...............................................................................................6 3.1.6 Bacterial leaf scorch of shade -

Research Progress Reports for Pierce's Disease and Other

2019 Research Progress Reports Research Progress Reports Pierce’s Disease and Other Designated Pests and Diseases of Winegrapes - December 2019 - Compiled by: Pierce’s Disease Control Program California Department of Food and Agriculture Sacramento, CA 95814 2019 Research Progress Reports Editor: Thomas Esser, CDFA Cover Design: Sean Veling, CDFA Cover Photograph: Photo by David Köhler on Unsplash Cite as: Research Progress Reports: Pierce’s Disease and Other Designated Pests and Diseases of Winegrapes. December 2019. California Department of Food and Agriculture, Sacramento, CA. Available on the Internet at: https://www.cdfa.ca.gov/pdcp/Research.html Acknowledgements: Many thanks to the scientists and cooperators conducting research on Pierce’s disease and other pests and diseases of winegrapes for submitting reports for inclusion in this document. Note to Readers: The reports in this document have not been peer reviewed. 2019 Research Progress Reports TABLE OF CONTENTS Section 1: Xylella fastidiosa and Pierce’s Disease REPORTS • Addressing Knowledge Gaps in Pierce’s Disease Epidemiology: Underappreciated Vectors, Genotypes, and Patterns of Spread Rodrigo P.P. Almeida, Monica L. Cooper, Matt Daugherty, and Rhonda Smith ......................2 • Testing of Grapevines Designed to Block Vector Transmission of Xylella fastidiosa Rodrigo P.P. Almeida ..............................................................................................................11 • Field-Testing Transgenic Grapevine Rootstocks Expressing Chimeric Antimicrobial -

Risk and Economic Impact of Phylloxera in South Australia’S Viticultural Regions

The Risk and Economic Impact of Phylloxera in South Australia’s Viticultural Regions Volume 1, Main Report A report prepared for Prepared by and EconSearch Pty Ltd PO Box 746 Unley BC SA 5061 Tel: 08 8357 9560 Fax: 08 8357 2299 March, 2002 PGIBSA The Risk and Economic Impact of Phylloxera in SA’s Viticultural Regions Contents List of Tables.................................................................................................................. iv List of Figures ................................................................................................................. v Abbreviations ................................................................................................................. vi Acknowledgements........................................................................................................vii Executive Summary ......................................................................................................viii 1. Introduction ..............................................................................................................1 1.1 Background to Study........................................................................................1 1.2 Key Viticultural Regions in South Australia ......................................................2 1.2.1 Description .............................................................................................2 1.2.2 Statistical information.............................................................................4 1.3 Classification of