Leora Kahn and Paul Lowe "Facing up to Rape in Conflict: Challenging

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Life of Fear and Flight

A LIFE OF FEAR AND FLIGHT The Legacy of LRA Brutality in North-East Democratic Republic of the Congo We fled Gilima in 2009, as the LRA started attacking there. From there we fled to Bangadi, but we were confronted with the same problem, as the LRA was attacking us. We fled from there to Niangara. Because of insecurity we fled to Baga. In an attack there, two of my children were killed, and one was kidnapped. He is still gone. Two family members of my husband were killed. We then fled to Dungu, where we arrived in July 2010. On the way, we were abused too much by the soldiers. We were abused because the child of my brother does not understand Lingala, only Bazande. They were therefore claiming we were LRA spies! We had to pay too much for this. We lost most of our possessions. Once in Dungu, we were first sleeping under a tree. Then someone offered his hut. It was too small with all the kids, we slept with twelve in one hut. We then got another offer, to sleep in a house at a church. The house was, however, collapsing and the owner chased us. He did not want us there. We then heard that some displaced had started a camp, and that we could get a plot there. When we had settled there, it turned out we had settled outside of the borders of the camp, and we were forced to leave. All the time, we could not dig and we had no access to food. -

Human Rights Watch

HUMAN RIGHTS WATCH LEAVE NO ONE BEHIND Persons with Disabilities in Humanitarian Emergencies Copyright © 2016 Human Rights Watch All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America ISBN: 978-1-6231-33498 Cover design by Rafael Jimenez. Human Rights Watch defends the rights of people worldwide. We scrupulously investigate abuses, expose the facts widely, and pressure those with power to respect rights and secure justice. Human Rights Watch is an independent, international organization that works as part of a vibrant movement to uphold human dignity and advance the cause of human rights for all. Human Rights Watch is an international organization with staff in more than 40 countries, and offices in Amsterdam, Beirut, Berlin, Brussels, Chicago, Geneva, Goma, Johannesburg, London, Los Angeles, Moscow, Nairobi, New York, Paris, San Francisco, Sydney, Tokyo, Toronto, Tunis, Washington DC, and Zurich. For more information, please visit our website: http://www.hrw.org LEAVE NO ONE BEHIND Persons with Disabilities in Humanitarian Emergencies SUMMARY ...............................................................................................................................= RECOMMENDATIONS ...............................................................................................................? ABANDONMENT AND OBSTACLES IN FLEEING ............................................................................;; ACCESS TO FOOD, SANITATION, AND MEDICAL SERVICES ..........................................................;> ACCESS TO EDUCATION -

Book XVIII Prizes and Organizations Editor: Ramon F

8 88 8 88 Organizations 8888on.com 8888 Basic Photography in 180 Days Book XVIII Prizes and Organizations Editor: Ramon F. aeroramon.com Contents 1 Day 1 1 1.1 Group f/64 ............................................... 1 1.1.1 Background .......................................... 2 1.1.2 Formation and participants .................................. 2 1.1.3 Name and purpose ...................................... 4 1.1.4 Manifesto ........................................... 4 1.1.5 Aesthetics ........................................... 5 1.1.6 History ............................................ 5 1.1.7 Notes ............................................. 5 1.1.8 Sources ............................................ 6 1.2 Magnum Photos ............................................ 6 1.2.1 Founding of agency ...................................... 6 1.2.2 Elections of new members .................................. 6 1.2.3 Photographic collection .................................... 8 1.2.4 Graduate Photographers Award ................................ 8 1.2.5 Member list .......................................... 8 1.2.6 Books ............................................. 8 1.2.7 See also ............................................ 9 1.2.8 References .......................................... 9 1.2.9 External links ......................................... 12 1.3 International Center of Photography ................................. 12 1.3.1 History ............................................ 12 1.3.2 School at ICP ........................................ -

Author of 'Forgotten' Addresses Capacity Crowd

THE MONTHLY NEWSLETTER OF THE OVERSEAS PRESS CLUB OF AMERICA, NEW YORK, NY • November 2015 Author of ‘Forgotten’ Addresses Capacity Crowd EVENT RECAP a top editor at Newsweek, moderated the discussion. By Chad Bouchard He asked Hervieux why this Author and freelance journalist unit of black soldiers had Linda Hervieux drew a record-break- been picked for this danger- ing crowd of more than 100 attend- ous assignment. ees at Club Quarters on Nov. 4 for Hervieux said some an OPC Book Night to launch For- people theorized that it was gotten: The Untold Story of D-Day’s meant to be a suicide mis- Black Heroes, at Home and at War. sion, but she thinks the deci- Carrie Crow Hervieux told the standing-room sion to send them had more -only crowd that when she started re- to do with growing pres- Linda Hervieux, right, points to a barrage bal- loon as moderator Mark Whitaker looks on. searching the men of the 320th Bar- sure from groups like the rage Balloon Battalion – the only unit NAACP and possibly even serve Germans. of African American combat soldiers from Eleanor Roosevelt, who had In Virginia, a black man could still to land on D-Day – a central question advocated for better treatment of be charged with rape for making eye emerged. black soldiers, to provide more in- contact with a white woman. “I wanted to know why I didn’t teresting and important assignments When en route from Tennessee to know this history,” she said. for them. New York, black soldiers in segre- The Barrage Balloon Battalion Black soldiers not only faced the gated cars drew the curtains because deployed balloons on tethers to tan- horrors of war – they also experi- “Dixie whites often fired at train cars gle low-flying aircraft and prevent enced apalling racism on the home- carrying black men.” strafing attacks during the D-Day in- front. -

CHILD SOLDIERS CHILD Girl Soldiers and Others Gathered at a Communist Party of Nepal (Maoist) Event in Tila, Rolpa District, Nepal

CHILD SOLDIERS Girl soldiers and others gathered at a Communist Party of Nepal (Maoist) event in Tila, Rolpa district, Nepal. CHILD SOLDIERS Cover photo © Marcus Bleasdale 2005 The Coalition to Stop the Use of Child Soldiers was formed in May 1998 by leading non- governmental organizations to end the recruitment and use of child soldiers, both boys 2008 Report Global and girls, to secure their demobilization, and to promote their reintegration into their communities. It works to achieve this through advocacy and public education, research Global Report 2008 and monitoring, and network development and capacity building. The Coalition’s Steering Committee members are: Amnesty International, Defence for Children International, Human Rights Watch, International Federation Terre des Hommes, International Save the Children Alliance, Jesuit Refugee Service, and the Quaker United Nations Office – Geneva. The Coalition has regional representatives in Africa, the Americas, Asia and the Middle East and national networks in about 30 countries. The Coalition unites local, national and international organizations, as well as youth, experts and concerned individuals from every region of the world. COALITION TO STOP THE USE OF CHILD SOLDIERS www.child-soldiers.org COALITION TO STOP THE USE OF CHILD SOLDIERS CHILD SOLDIERS Girl soldiers and others gathered at a Communist Party of Nepal (Maoist) event in Tila, Rolpa district, Nepal. CHILD SOLDIERS Cover photo © Marcus Bleasdale 2005 The Coalition to Stop the Use of Child Soldiers was formed in May 1998 by leading non- governmental organizations to end the recruitment and use of child soldiers, both boys 2008 Report Global and girls, to secure their demobilization, and to promote their reintegration into their communities. -

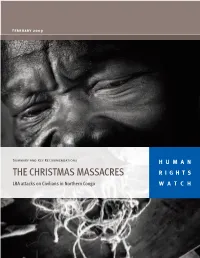

DRC 0209 Insert

February 2009 Summary and Key Recommendations HUMAN THE CHRISTMAS MASSACRES RIGHTS LRA attacks on Civilians in Northern Congo WATCH Items of clothing found at the massacre site in Batande. Human Rights Watch researchers and local civil society members went to massacre sites to document the location of graves and to collect remaining evidence. The team found the cords used to tie of the victims, the blood-stained bats and items of clothing, all of which were moved to a secure location. © 2009 Marcus Bleasdale/VII Cords used to tie up victims found at one massacre site. Human Rights Watch researchers and local civil society members went to the massacre sites to document the location of graves and to collect remaining evidence. The team found the cords used to tie of the victims, the blood-stained bats and items of clothing, all of which were moved to a secure location. © 2009 Marcus Bleasdale/VII THE CHRISTMAS MASSACRES (right) An axe and sticks used by the LRA in Faradje to kill civilians. At least 143 civilians were killed in Faradje on Christmas day. © 2009 Human Rights Watch The LRA were quick at killing. It did not take them very long and they said nothing while they were doing it. They killed all 26. I was horrified. I knew all these people. They were my family, my friends, my neighbors. When they finished I slipped away and went to my home, where I sat trembling all over. — A 72-year-old man who hid in the bushes and watched as the LRA killed his family on Christmas day in Batande, near Doruma. -

CENTRAL AFRICAN REPUBLIC RIGHTS Materials Published by Human Rights Watch WATCH Since the March 2013 Seleka Coup

HUMAN CENTRAL AFRICAN REPUBLIC RIGHTS Materials Published by Human Rights Watch WATCH since the March 2013 Seleka Coup Central African Republic Materials Published by Human Rights Watch since the March 2013 Seleka Coup Copyright © 2014 Human Rights Watch All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America Cover design by Rafael Jimenez Human Rights Watch is dedicated to protecting the human rights of people around the world. We stand with victims and activists to prevent discrimination, to uphold political freedom, to protect people from inhumane conduct in wartime, and to bring offenders to justice. We investigate and expose human rights violations and hold abusers accountable. We challenge governments and those who hold power to end abusive practices and respect international human rights law. We enlist the public and the international community to support the cause of human rights for all. Human Rights Watch is an international organization with staff in more than 40 countries, and offices in Amsterdam, Beirut, Berlin, Brussels, Chicago, Geneva, Goma, Johannesburg, London, Los Angeles, Moscow, Nairobi, New York, Paris, San Francisco, Tokyo, Toronto, Tunis, Washington DC, and Zurich. For more information, please visit our website: http://www.hrw.org Central African Republic Materials Published Since the Seleka Coup This document contains much of Human Rights Watch’s reporting on the human rights situation in the Central African Republic following the March 24, 2013 coup d’état against former President François Bozizé. For all of Human Rights Watch’s work on Central African Republic, including photographs, satellite imagery, and reports, please visit our website: https://www.hrw.org/africa/central-african-republic. -

2010-11 Annual Report

2010-11 Annual Report 2010-11 Annual Report, Institute for Global Leadership, Tufts University 1 2 2010-11 Annual Report, Institute for Global Leadership, Tufts University Institute for Global Leadership 2010-11 Annual Report 2010-11 Annual Report, Institute for Global Leadership, Tufts University 3 4 2010-11 Annual Report, Institute for Global Leadership, Tufts University Table of Contents Mission Statement // 7 IGL Programs // 8 The Year in Numbers // 13 Transitions // 14 EPIIC // 16 Global Research, Internships, and Conferences // 32 Inquiry // 35 Dr. Jean Mayer Global Citizenship Awards // 42 TILIP // 48 INSPIRE // 51 BUILD // 53 NIMEP // 60 EXPOSURE // 66 Engineers Without Borders // 69 Tufts Energy Conference // 71 ALLIES // 75 Synaptic Scholars // 83 Empower // 93 RESPE // 99 Discourse // 100 PPRI // 101 Collaborations // 105 School of Engineering // 105 Project on Justice in Times of Transition // 106 GlobalPost // 107 Alumni Programs // 110 Sisi ni Amani // 110 Collaborative Transitions Africa // 112 New Initiatives // 114 Oslo Scholars Program // 114 Program on Narrative and Documentary Practice // 117 Solar for Gaza and Sderot // 121 Gerald R Gill Oral History Prize // 130 Curriculum Development // 131 Academic Awards // 136 Benefactors // 138 External Advisory Board // 147 2010-11 Annual Report, Institute for Global Leadership, Tufts University 5 6 2010-11 Annual Report, Institute for Global Leadership, Tufts University MISSION STATEMENT The mission of the Institute for Global Leadership at Tufts University is to prepare new generations of critical thinkers for effective and ethical leadership, ready to act as global citizens in addressing the world’s most pressing problems. In 2005, IGL was designated as a university cross-school program with the objective of enhancing the interdisciplin- ary quality and engaged nature of a Tufts education and serving as an incubator of innovative ways to help students understand and engage difficult and compelling global issues. -

What Future? RIGHTS Street Children in the Democratic Republic of Congo WATCH April 2006 Volume 18, No

Democratic Republic of Congo HUMAN What Future? RIGHTS Street Children in the Democratic Republic of Congo WATCH April 2006 Volume 18, No. 2(A) What Future? Street Children in the Democratic Republic of Congo I. Summary ..................................................................................................................................... 1 II. Recommendations ................................................................................................................... 6 Recommendations for the pre-election period .................................................................... 6 Recommendations for the post-election period................................................................... 7 III. Methods.................................................................................................................................11 IV. Background ...........................................................................................................................12 V. Abuses Against Street Children ...........................................................................................15 Police and Military Abuse......................................................................................................15 Physical abuse......................................................................................................................15 Extortion..............................................................................................................................17 Sexual abuse of girls -

The Curse of Gold Democratic Republic of Congo

The Curse of Gold Democratic Republic of Congo Human Rights Watch Copyright © 2005 by Human Rights Watch. All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America ISBN: 1-56432-332-3 Cover photo: Miners working in the grueling conditions of an open pit gold mine in Watsa, northeastern Democratic Republic of Congo. © 2004 Marcus Bleasdale. Cover design by Rafael Jimenez Human Rights Watch 350 Fifth Avenue, 34th floor New York, NY 10118-3299 USA Tel: 1-(212) 290-4700, Fax: 1-(212) 736-1300 [email protected] 1630 Connecticut Avenue, N.W., Suite 500 Washington, DC 20009 USA Tel:1-(202) 612-4321, Fax:1-(202) 612-4333 [email protected] 2nd Floor, 2-12 Pentonville Road London N1 9HF, UK Tel: 44 20 7713 1995, Fax: 44 20 7713 1800 [email protected] Rue Van Campenhout 15, 1000 Brussels, Belgium Tel: 32 (2) 732-2009, Fax: 32 (2) 732-0471 [email protected] 9 rue Cornavin 1201 Geneva Tel: + 41 22 738 04 81, Fax: + 41 22 738 17 91 [email protected] Web Site Address: http://www.hrw.org Listserv address: To receive Human Rights Watch news releases by email, subscribe to the HRW news listserv of your choice by visiting http://hrw.org/act/subscribe- mlists/subscribe.htm Human Rights Watch is dedicated to protecting the human rights of people around the world. We stand with victims and activists to prevent discrimination, to uphold political freedom, to protect people from inhumane conduct in wartime, and to bring offenders to justice. We investigate and expose human rights violations and hold abusers accountable. -

OPC Awards Showcase Ambitious Reporting in 2014

THE MONTHLY NEWSLETTER OF THE OVERSEAS PRESS CLUB OF AMERICA, NEW YORK, NY • May 2015 OPC Awards Showcase Ambitious Reporting in 2014 and Atish Saha’s dis- EVENT RECAP section of a factory By Trish Anderton collapse in Bangla- In tones ranging from defiance desh. While heavy to joy and mourning to optimism, hitters like The New foreign correspondents gathered on York Times were April 30 to celebrate the vitality of well represented, their profession. less traditional or- “It’s time for us to take our story ganizations like Hu- back from the handwringers,” Dean man Rights Watch, Baquet, executive editor of The New Medium/Matter and York Times, proclaimed in his keynote HBO Real Sports address at the Overseas Press Club with Bryant Gumbel Michael Dames Annual Awards Dinner. “We need also turned up on the Keynote speaker Dean Baquet. to scream about the fact that there is winners’ list. Chivers described the secrecy and huge and ambitious work being done Motlagh started his reportage oppression he faced trying to discov- in the old places like The New York several months after the Rana Plaza er how many U.S. soldiers had been Times, the Los Angeles Times and disaster, which claimed more than poisoned by abandoned Iraqi chemi- the Washington Post, and in the new 1,100 lives. He said he drew inspira- cal weapons. places like BuzzFeed and Vice.” tion from Saha’s unsparing photos. “We like to think it’s Uzbekistan The same digital technologies that “He had worked the scene of the that acts like that, but you’re in a have turned the industry’s business tragedy for three weeks, every day, country that does too.” model upside down have also given it day in and day out, pouring every- Secrecy and danger were under- new tools and “enormous new audi- thing into his photographs,” Motlagh currents running through the evening. -

Young People and Armed Groups in the Central African Republic

YOUNG PEOPLE AND ARMED GROUPS IN THE CENTRAL AFRICAN REPUBLIC: VOICES FROM BOSSANGOA Report YOUNG PEOPLE AND ARMED GROUPS IN THE CENTRAL AFRICAN REPUBLIC: VOICES FROM BOSSANGOA (OUHAM) OCTOBER 2020 AcKNOWLEDGEMENTS AND DISCLAIMER: This report was written by Ben Shepherd and Lisa Heinzel for Conciliation Resources with guidance and support from Kennedy Tumutegyereize, Theophane Ngbaba and Basile Semba. It was produced by Conciliation Resources in partnership with Association pour l’Action Humanitaire en Centrafrique (AAHC). Conciliation Resources is grateful to the lead researcher Pierre-Marie Kporon and the research team, including staff members of AAHC, who supported the development of the final methodology, conducted the Listening Exercise in the field and contributed to the analysis of the findings. This publication has been produced with generous financial support from the UN Secretary General’s Peacebuilding Fund (PBF) and UK aid from the UK government. The contents of the publication are the sole responsibility of Conciliation Resources and the views expressed do not necessarily reflect the position of the Peacebuilding Fund or the UK government. The Listening Exercise was conducted as part of the ‘Alternatives to Violence: Strengthening youth-led peacebuilding in the Central African Republic’ and ‘ Smart Peace’ projects. The Alternatives to Violence project was funded by the United Nations Peacebuilding Fund’s Gender and Youth Peace Initiative (GYPI) and was implemented by Conciliation Resources, War Child UK, Femme Homme Action Plus (FHAP) and AAHC between December 2018 and September 2020. It worked with 600 young people in Bossangoa and Paoua sub-prefectures with the aim of strengthening young people’s role in peacebuilding at the local, prefectural and national level, while also increasing their resilience through increased economic opportunities and psychosocial coping skills.