Young People and Armed Groups in the Central African Republic

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Children Born of War

Children Born of War 1) General Becirbasic, Belma and Dzenana Secic, 2002, ‘Invisible Casualties of War’, Star Magazine, Sarajevo, BCR No. 383S Carpenter, R. Charli (ed.),Born of War. Protecting Children of Sexual Violence Survivors in Conflict Zones (Bloomfield: Kumarian Press, 2007) Carpenter, Charli R., ‘International Agenda-Setting in World Politics: Issue Emergence and Non-Emergence Around Children and Armed Conflict’, (2005) [http://www.du.edu/gsis/hrhw/working/2005/30-carpenter-2005.pdf] D.Costa, Bina, War Babies: The Question of National Honour in the Gendered Construction of Nationalism: From Partition to Creation (unpublished PhD thesis, Australian National University, 2003) [http://www.drishtipat.org/1971/docs/warbabies_bina.pdf] Ismail, Zahra, Emerging from the Shadows. Finding a Place for Children Born of War (unpublished M.A. Thesis, European University Centre for Peace Studies, Austria, 2008) McKinley, James C. jr., ‘Legacy of Rwanda Violence: The Thousands Born of Rape’, New York Times, 25 September 1996 Mochmann, Ingvill C. 2017. Children Born of War – A Decade of International and Interdisciplinary Research. Historical Social Research 42 (1): 320-346. doi: 10.12759/hsr.42.2017.1.320-346. Parsons M. (ed), Children. The Invisible Victims of War (DSM, 2008) Voicu, Bogdan und Ingvill C. Mochmann, 2014: Social Trust and Children Born of War. Social Change Review 12(2): 185-212 Westerlund, Lars (ed.), Children of German Soldiers: Children of Foreign Soldiers in Finland 1940—1948 , vol. 1 (Helsinki: Painopaikka Nord Print, 2011) Westerlund, Lars (ed.), The Children of Foreign Soldiers in Finland, Norway, Denmark, Austria, Poland and Occupied Soviet Karelia. Children of Foreign Soldiers in Finland 1940– 1948 vol. -

The Psychological Impact of Child Soldiering

Chapter 14 The Psychological Impact of Child Soldiering Elisabeth Schauer and Thomas Elbert Abstract With almost 80% of the fighting forces composed of child soldiers, this is one characterization of the ‘new wars,’ which constitute the dominant form of violent conflict that has emerged only over the last few decades. The development of light weapons, such as automatic guns suitable for children, was an obvious pre- requisite for the involvement of children in modern conflicts that typically involve irregular forces, that target mostly civilians, and that are justified by identities, although the economic interests of foreign countries and exiled communities are usually the driving force. Motivations for child recruitment include children’s limited ability to assess risks, feelings of invulnerability, and shortsightedness. Child soldiers are more often killed or injured than adult soldiers on the front line. They are less costly for the respective group or organization than adult recruits, because they receive fewer resources, including less and smaller weapons and equipment. From a different per- spective, becoming a fighter may seem an attractive possibility for children and adolescents who are facing poverty, starvation, unemployment, and ethnic or polit- ical persecution. In our interviews, former child soldiers and commanders alike reported that children are more malleable and adaptable. Thus, they are easier to indoctrinate, as their moral development is not yet completed and they tend to listen to authorities without questioning them. Child soldiers are raised in an environment of severe violence, experience it, and subsequently often commit cruelties and atrocities of the worst kind. This repeated exposure to chronic and traumatic stress during development leaves the children with mental and related physical ill-health, notably PTSD and severe personality E. -

HDPT CAR Info Bulletin 98Eng

Bulletin 98 | 2/03 – 9/03/09 | Humanitarian and Development Partnership Team | RCA www.hdptcar.net Shortly before the Inclusive Political Dialogue was News Bulletin held, the FDPC broke the peace accord signed in 2 - 9 March 2009 Syrte in February 2007 with an ambush on Central African armed forces (FACA) in Moyenne-Sido, close to the border with Chad. In another recent incident, on the 20 th of February, FDPC fighters attacked the Highlights village of Batangafo in CAR’s North West. - Presidential Guard intervention leads to the Current events death of a police chief 4 billion FCFA for CAR’s energy sector - Departure of François Lonseny Fall, Special Representative for the UN’s Secretary General A finance agreement of 4 billion FCFA was signed on in the Central African Republic the 6th of March to improve electrical production facilities in Boali, 60 kilometers from Bangui. Present - First satellite clinic opened by NGO ‘Emergency’ at the signing were Minister of State for Mines and Water Power Sylvain Ndoutingai, the Minister for Planning, the Economy and International Cooperation Background and security Sylvain Malko as well as the World Bank’s Police chief killed; local protests Operational Director in CAR Mary Barton-Dock. An intervention by the Presidential Guard in Bangui’s This funding aims to reduce the number of power cuts Miskine district took a dramatic turn on the evening of which can last up to eight hours in some of Bangui’s Thursday the 5th of March. According to various neighbourhoods. Mary Barton-Dock pointed out that sources, the police Chief Samuel Samba was this emergency project comes in response to the seriously injured when members of the Presidential energy crisis, a response which fits into the World Guard attempted to disarm him. -

Central African Republic Emergency Update #2

Central African Republic Emergency Update #2 Period Covered 18-24 December 2013 [1] Highlights There are currently some 639,000 internally displaced people in the Central African Republic (CAR), including more than 210,000 in Bangui in over 40 sites. UNHCR submitted a request to the Humanitarian Coordinator for the activation of the Camp Coordination and Camp Management Cluster. Since 14 December, UNHCR has deployed twelve additional staff to Bangui to support UNHCR’s response to the current IDP crisis. Some 1,200 families living at Mont Carmel, airport and FOMAC/Lazaristes Sites were provided with covers, sleeping mats, plastic sheeting, mosquito domes and jerrycans. About 50 tents were set up at the Archbishop/Saint Paul Site and Boy Rabe Monastery. From 19 December to 20 December, UNHCR together with its partners UNICEF and ICRC conducted a rapid multi- sectoral assessment in IDP sites in Bangui. Following the declaration of the L3 Emergency, UNHCR and its partners have started conducting a Multi- Cluster/Sector Initial Rapid Assessment (MIRA) in Bangui and the northwest region. [2] Overview of the Operation Population Displacement 2013 Funding for the Operation Funded (42%) Funding Gap (58%) Total 2013 Requirements: USD 23.6M Partners Government agencies, 22 NGOs, FAO, BINUCA, OCHA, UNAIDS, UNDP, UNFPA, UNICEF, WFP and WHO. For further information, please contact: Laroze Barrit Sébastien, Phone: 0041-79 818 80 39, E-mail: [email protected] Central African Republic Emergency Update #2 [2] Major Developments Timeline of the current -

A Life of Fear and Flight

A LIFE OF FEAR AND FLIGHT The Legacy of LRA Brutality in North-East Democratic Republic of the Congo We fled Gilima in 2009, as the LRA started attacking there. From there we fled to Bangadi, but we were confronted with the same problem, as the LRA was attacking us. We fled from there to Niangara. Because of insecurity we fled to Baga. In an attack there, two of my children were killed, and one was kidnapped. He is still gone. Two family members of my husband were killed. We then fled to Dungu, where we arrived in July 2010. On the way, we were abused too much by the soldiers. We were abused because the child of my brother does not understand Lingala, only Bazande. They were therefore claiming we were LRA spies! We had to pay too much for this. We lost most of our possessions. Once in Dungu, we were first sleeping under a tree. Then someone offered his hut. It was too small with all the kids, we slept with twelve in one hut. We then got another offer, to sleep in a house at a church. The house was, however, collapsing and the owner chased us. He did not want us there. We then heard that some displaced had started a camp, and that we could get a plot there. When we had settled there, it turned out we had settled outside of the borders of the camp, and we were forced to leave. All the time, we could not dig and we had no access to food. -

History, External Influence and Political Volatility in the Central African Republic (CAR)

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Journal for the Advancement of Developing Economies Economics Department 2014 History, External Influence and oliticalP Volatility in the Central African Republic (CAR) Henry Kam Kah University of Buea, Cameroon Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/jade Part of the Econometrics Commons, Growth and Development Commons, International Economics Commons, Political Economy Commons, Public Economics Commons, and the Regional Economics Commons Kam Kah, Henry, "History, External Influence and oliticalP Volatility in the Central African Republic (CAR)" (2014). Journal for the Advancement of Developing Economies. 5. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/jade/5 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Economics Department at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal for the Advancement of Developing Economies by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. Journal for the Advancement of Developing Economies 2014 Volume 3 Issue 1 ISSN:2161-8216 History, External Influence and Political Volatility in the Central African Republic (CAR) Henry Kam Kah University of Buea, Cameroon ABSTRACT This paper examines the complex involvement of neighbors and other states in the leadership or political crisis in the CAR through a content analysis. It further discusses the repercussions of this on the unity and leadership of the country. The CAR has, for a long time, been embroiled in a crisis that has impeded the unity of the country. It is a failed state in Africa to say the least, and the involvement of neighboring and other states in the crisis in one way or the other has compounded the multifarious problems of this country. -

Annual Report 2017

Annual Report 2017 Mission Vision War Child’s mission is to work with war-affected War Child’s vision is for a world communities to help children reclaim their childhood where no child knows war. through access to education, opportunity and justice. War Child takes an active role in raising public awareness around the impact of war on communities and the shared responsibility to act. War Child Canada Board of Directors Michael Eizenga (Chair) Denise Donlon Nils Engelstad Omar Khan Jeffrey Orridge Elliot Pobjoy All photographs © War Child Canada Cover illustration by Eric Hanson © Eric Hanson Beneficiary names have been changed for their own protection. Letter from the Founder and Chair Dear Friends, To listen to some commentators talk about human rights, you would think that they represent the most restrictive system of regulations, designed to threaten the sovereignty of democratically elected governments. But take a look at the Universal Declaration and the Convention on the Rights of the Child and it is hard to see where the controversy lies. The right to life, liberty and security. The right to freedom from slavery or torture. The right to free expression. The right to an education. The right to be protected from harm. These are not onerous obligations on government but rather the basic protections one should expect, particularly for children, from a functioning state. The Convention on the Rights of the Child is War Child Canada’s guiding document. As you will read in this report, everything we do is in support of the rights enshrined within it. While the Convention is directed at governments, the responsibilities it describes can be equally applied to non-government organizations, community leaders and ordinary citizens. -

OCHA CAR Snapshot Incident

CENTRAL AFRICAN REPUBLIC Overview of incidents affecting humanitarian workers January - May 2021 CONTEXT Incidents from The Central African Republic is one of the most dangerous places for humanitarian personnel with 229 1 January to 31 May 2021 incidents affecting humanitarian workers in the first five months of 2021 compared to 154 during the same period in 2020. The civilian population bears the brunt of the prolonged tensions and increased armed violence in several parts of the country. 229 BiBiraorao 124 As for the month of May 2021, the number of incidents affecting humanitarian workers has decreased (27 incidents against 34 in April and 53 in March). However, high levels of insecurity continue to hinder NdéléNdélé humanitarian access in several prefectures such as Nana-Mambéré, Ouham-Pendé, Basse-Kotto and 13 Ouaka. The prefectures of Haute-Kotto (6 incidents), Bangui (4 incidents), and Mbomou (4 incidents) Markounda Kabo Bamingui were the most affected this month. Bamingui 31 5 Kaga-Kaga- 2 Batangafo Bandoro 3 Paoua Batangafo Bandoro Theft, robbery, looting, threats, and assaults accounted for almost 60% of the incidents (16 out of 27), 2 7 1 8 1 2950 BriaBria Bocaranga 5Mbrès Djéma while the 40% were interferences and restrictions. Two humanitarian vehicles were stolen in May in 3 Bakala Ippy 38 2 Bossangoa Bouca 13 Bozoum Bouca Ippy 3 Bozoum Dekoa 1 1 Ndélé and Bangui, while four health structures were targeted for looting or theft. 1 31 2 BabouaBouarBouar 2 4 1 Bossangoa11 2 42 Sibut Grimari Bambari 2 BakoumaBakouma Bambouti -

The Central African Republic Diamond Database—A Geodatabase of Archival Diamond Occurrences and Areas of Recent Artisanal and Small-Scale Diamond Mining

Prepared in cooperation with the U.S. Agency for International Development under the auspices of the U.S. Department of State The Central African Republic Diamond Database—A Geodatabase of Archival Diamond Occurrences and Areas of Recent Artisanal and Small-Scale Diamond Mining Open-File Report 2018–1088 U.S. Department of the Interior U.S. Geological Survey Cover. The main road west of Bambari toward Bria and the Mouka-Ouadda plateau, Central African Republic, 2006. Photograph by Peter Chirico, U.S. Geological Survey. The Central African Republic Diamond Database—A Geodatabase of Archival Diamond Occurrences and Areas of Recent Artisanal and Small-Scale Diamond Mining By Jessica D. DeWitt, Peter G. Chirico, Sarah E. Bergstresser, and Inga E. Clark Prepared in cooperation with the U.S. Agency for International Development under the auspices of the U.S. Department of State Open-File Report 2018–1088 U.S. Department of the Interior U.S. Geological Survey U.S. Department of the Interior RYAN K. ZINKE, Secretary U.S. Geological Survey James F. Reilly II, Director U.S. Geological Survey, Reston, Virginia: 2018 For more information on the USGS—the Federal source for science about the Earth, its natural and living resources, natural hazards, and the environment—visit https://www.usgs.gov or call 1–888–ASK–USGS. For an overview of USGS information products, including maps, imagery, and publications, visit https://store.usgs.gov. Any use of trade, firm, or product names is for descriptive purposes only and does not imply endorsement by the U.S. Government. Although this information product, for the most part, is in the public domain, it also may contain copyrighted materials as noted in the text. -

Central African Republic (CAR) in Mid-March, the Ministry of Health and Population Confirmed 4,711 Positive Cases Including 62 Deaths (As of 30 August)

Central African CentralRepublic African Humanitarian Republic Situation Humanitarian Situation Situation in Numbers ©Reporting UNICEFCAR/20 Period:20/A.JONNAERT July and August 2020 © UNICEF/2020/P.SEMBA 1,200,000 Highlights children in need of humanitarian assistance Since the first case of COVID-19 was detected in the Central African Republic (CAR) in mid-March, the Ministry of Health and Population confirmed 4,711 positive cases including 62 deaths (as of 30 August). All the 2,600,000 seven health regions of the countries have reported cases, with the capital people in need Bangui being the most affected by the pandemic, where an estimated 17% (OCHA, August 2020) of the population live. Since July the government's new diagnostic strategy limits testing to suspected cases and to those considered as “people at risk”. 641,292 Internally displaced people (IDPs) In July and August, CAR continued to experience clashes armed conflicts. (CMP, August 2020) UNICEF and its partners supported continuing learning through radio education programmes and 23,076 children benefitted from lessons 622,150 broadcasting. # of pending and registered refugees 12,159 people including 10,288 children under 5 received free essential care in conflict-affected areas and 2,094 children aged from 6 to 59 months (UNHCR, August 2020) suffering from severe acute malnutrition (SAM) were treated. 5,610 people gained access to safe water for drinking, cooking and personal hygiene in conflict-affected areas (including IDP sites) UNICEF Appeal 2020 US$ 57 million Funding status* ($US) UNICEF’s Response SAM admissions 35% © UNICEF/2020/P.SEMBA Nutrition Polio vaccination 97% Health © UNICEFCAR/2020/A.FRISETTI Safe water access 42% WASH Children relased from armed 35% *Available funds include those groups Child received for the current year of Protection appeal as well as the carry-forward © UNICEFCAR/2019/B.MATOUS Education access 53% from the previous year. -

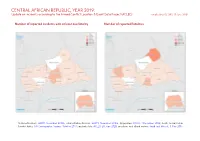

CENTRAL AFRICAN REPUBLIC, YEAR 2019: Update on Incidents According to the Armed Conflict Location & Event Data Project (ACLED) Compiled by ACCORD, 23 June 2020

CENTRAL AFRICAN REPUBLIC, YEAR 2019: Update on incidents according to the Armed Conflict Location & Event Data Project (ACLED) compiled by ACCORD, 23 June 2020 Number of reported incidents with at least one fatality Number of reported fatalities National borders: GADM, November 2015b; administrative divisions: GADM, November 2015a; Abyei Area: SSNBS, 1 December 2008; South Sudan/Sudan border status: UN Cartographic Section, October 2011; incident data: ACLED, 20 June 2020; coastlines and inland waters: Smith and Wessel, 1 May 2015 CENTRAL AFRICAN REPUBLIC, YEAR 2019: UPDATE ON INCIDENTS ACCORDING TO THE ARMED CONFLICT LOCATION & EVENT DATA PROJECT (ACLED) COMPILED BY ACCORD, 23 JUNE 2020 Contents Conflict incidents by category Number of Number of reported fatalities 1 Number of Number of Category incidents with at incidents fatalities Number of reported incidents with at least one fatality 1 least one fatality Violence against civilians 104 57 286 Conflict incidents by category 2 Strategic developments 71 0 0 Development of conflict incidents from 2010 to 2019 2 Battles 68 40 280 Protests 35 0 0 Methodology 3 Riots 19 4 4 Conflict incidents per province 4 Explosions / Remote 2 2 3 violence Localization of conflict incidents 4 Total 299 103 573 Disclaimer 6 This table is based on data from ACLED (datasets used: ACLED, 20 June 2020). Development of conflict incidents from 2010 to 2019 This graph is based on data from ACLED (datasets used: ACLED, 20 June 2020). 2 CENTRAL AFRICAN REPUBLIC, YEAR 2019: UPDATE ON INCIDENTS ACCORDING TO THE ARMED CONFLICT LOCATION & EVENT DATA PROJECT (ACLED) COMPILED BY ACCORD, 23 JUNE 2020 Methodology on what level of detail is reported. -

1 FAITS ESSENTIELS • Regain De Tension À Gambo, Ouango Et Bema

République Centrafricaine : Région : Est, Bambari Rapport hebdo de la situation n o 32 (13 Aout 2017) Ce rapport a été produit par OCHA en collaboration avec les partenaires humanitaires. Il a été publié par le Sous-bureau OCHA Bambari et couvre la période du 7 au 13 Aout 2017. Sur le plan géographique, il couvre les préfectures de la Ouaka, Basse Kotto, Haute Kotto, Mbomou, Haut-Mbomou et Vakaga. FAITS ESSENTIELS • Regain de tension à Gambo, Ouango et Bema tous dans la préfecture de Mbomou : nécessité d’un renforcement de mécanisme de protection civile dans ces localités ; • Rupture en médicament au Centre de santé de Kembé face aux blessés de guerre enregistrés tous les jours dans cette structure sanitaire ; • Environ 77,59% de personnes sur 28351 habitants de Zémio se sont déplacées suite aux hostilités depuis le 28 juin. CONTEXTES SECURITAIRE ET HUMANITAIRE Haut-Mbomou La situation sécurité est demeurée fragile cette semaine avec la persistance des menaces d’incursion des groupes armés dans la ville. Ces menaces Le 10 août, un infirmier secouriste a été tué par des présumés sujets musulmans dans le quartier Ayem, dans le Sud-Ouest de la ville. Les circonstances de cette exécution restent imprécises. Cet incident illustre combien les défis de protection dans cette ville nécessitent un suivi rapproché. Mbomou Les affrontements de la ville de Bangassou sont en train de connaitre un glissement vers les autres sous-préfectures voisines telles Gambo, Ouango et Béma. En effet, depuis le 03 aout les heurts se sont produits entre les groupes armés protagonistes à Gambo, localité située à 75 km de Bangassou sur l’axe Bangassou-Kembé-Alindao-Bambari.