Taosrewrite FINAL New Title Cover

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Record of the Istanbul Process 16/18 for Combating Intolerance And

2019 JAPAN SUMMARY REPORT TABLE OF CONTENTS EVENT SUMMARY .................................................................................................................................... 3 PLENARY SESSIONS ................................................................................................................................. 7 LAUNCHING THE 2019 G20 INTERFAITH FORUM.......................................................................... 7 FORMAL FORUM INAUGURATION – WORKING FOR PEACE, PEOPLE, AND PLANET: CHALLENGES TO THE G20 ............................................................................................................... 14 WHY WE CAN HOPE: PEACE, PEOPLE, AND PLANET ................................................................. 14 ACTION AGENDAS: TESTING IDEAS WITH EXPERIENCE FROM FIELD REALITIES ........... 15 IDEAS TO ACTION .............................................................................................................................. 26 TOWARDS 2020 .................................................................................................................................... 35 CLOSING PLENARY ............................................................................................................................ 42 PEACE WORKING SESSIONS ................................................................................................................ 53 FROM VILE TO VIOLENCE: FREEDOM OF RELIGION & BELIEF & PEACEBUILDING ......... 53 THE DIPLOMACY OF RELIGIOUS PEACEBUILDING .................................................................. -

JAPAN's MOST UNFORGETTABLE SHRINES Relaxing Is One Thing

JAPAN’S MOST UNFORGETTABLE SHRINES Relaxing is one thing, but to feel at peace, you need to step away from the neon signs and busy streets and explore the spiritual side of Japan. Shrines are an integral part of Japanese cultural tapestry. You will find these places of worship hidden in forest sandwiched between office towers on busy streets or clinging into mountain tops visiting them can be a spiritual experience, a chance to gain insights into Japanese tradition and history, or simply enjoy serene escape from the busy city life. Shrines are considered to be the residences of Kami (Shinto gods) and are used as places of worship. The names of Shinto shrines in Japan can end in –jinja, jingu (for Imperial shrines), or taisha. Shrines are built to serve the Shinto religious tradition and are characterized by a Torii gate at the entrance decorated with vermillion, and are guarded by fox, dog, or other animal statues. The architecture of a shrine typically includes a main sanctuary (honden), where the shrine’s sacred object is kept, and a worship hall (haiden), where people make prayers and offerings. Some shrines may have treasury buildings and stages for dance or theatre performances. There are close to 80,000 Shinto shrines in Japan and are of several different categories like: • Sengen shrines- dedicated to the Shinto deity of Mt. Fuji • Hachiman shrines- dedicated to the Kami of war • Inari shrines- dedicated to the Kami of huge harvest of grains • Kumano shrines - dedicated to the twelve Kami, three Grand Shrines in the three Kumano mountains • Tenjin shrines- dedicated to the Kami of Sugawara No Michizane, a politician and scholar FUSHIMI INARI SHRINE Fushimi Inari Shrine (伏見稲荷大社, Fushimi Inari Taisha) is an important Shinto shrine in southern Kyoto. -

The Otaku Phenomenon : Pop Culture, Fandom, and Religiosity in Contemporary Japan

University of Louisville ThinkIR: The University of Louisville's Institutional Repository Electronic Theses and Dissertations 12-2017 The otaku phenomenon : pop culture, fandom, and religiosity in contemporary Japan. Kendra Nicole Sheehan University of Louisville Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.library.louisville.edu/etd Part of the Comparative Methodologies and Theories Commons, Japanese Studies Commons, and the Other Religion Commons Recommended Citation Sheehan, Kendra Nicole, "The otaku phenomenon : pop culture, fandom, and religiosity in contemporary Japan." (2017). Electronic Theses and Dissertations. Paper 2850. https://doi.org/10.18297/etd/2850 This Doctoral Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by ThinkIR: The University of Louisville's Institutional Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ThinkIR: The University of Louisville's Institutional Repository. This title appears here courtesy of the author, who has retained all other copyrights. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE OTAKU PHENOMENON: POP CULTURE, FANDOM, AND RELIGIOSITY IN CONTEMPORARY JAPAN By Kendra Nicole Sheehan B.A., University of Louisville, 2010 M.A., University of Louisville, 2012 A Dissertation Submitted to the Faculty of the College of Arts and Sciences of the University of Louisville in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Humanities Department of Humanities University of Louisville Louisville, Kentucky December 2017 Copyright 2017 by Kendra Nicole Sheehan All rights reserved THE OTAKU PHENOMENON: POP CULTURE, FANDOM, AND RELIGIOSITY IN CONTEMPORARY JAPAN By Kendra Nicole Sheehan B.A., University of Louisville, 2010 M.A., University of Louisville, 2012 A Dissertation Approved on November 17, 2017 by the following Dissertation Committee: __________________________________ Dr. -

Gro Kristiansen.Pdf

KOORDINERENDE ENHET FOR HABILITERING OG REHABILITERING (KE) STYRKING AV KE I BERGEN KOMMUNE 24.oktober 2019 KOMPETENT | ÅPEN | PÅLITELIG | SAMFUNNSENGASJERT BERGEN KOMMUNE VIL: Tiltak 13: Etablere en synlig, velfungerende og tilgjengelig koordinerende enhet for habilitering og rehabilitering (KE). Tiltak 14: Utvikle et felles opplæringsprogram for kommunens ansatte om KE, individuell plan og koordinator, med særlig vekt på opplæring av koordinatorer. Felles for tre byrådsavdelinger BSBI, BBSI og BHO. Anita Brekke Røed, systemrådgiver koordinerende enhet for habilitering og rehabilitering (KE) Sentrale oppgaver for KE i kommunene • Sentral rolle i kommunens plan for habilitering og rehabilitering • Legge til rette for brukermedvirkning • Ha oversikt over tilbud innen habilitering og rehabilitering • Overordnet ansvar for IP og koordinator • Motta meldinger om behov for IP og koordinator (behov for langvarige og koordinerte tjenester) • Utarbeide rutiner for arbeidet med IP og koordinator • Oppnevning av koordinator • Kompetanseheving om IP og koordinator • Opplæring og veiledning av koordinatorer • Bidra til samarbeid på tvers av fagområder, nivåer og sektorer • Ivareta familieperspektivet • Sikre informasjon til befolkningen og samarbeidspartnere • Motta interne meldinger om mulig behov for habilitering og rehabilitering Koordinerende enhet – ledelsesforankret koordineringsarbeid BSBI BBSI BHO Koordinerende enheter (KE) En KE i hvert byområde Enhetsledere Systemrådgiver KE Systemkoordinator KE Deltagere i KE-møtene i fire byområder FYLLINGSDALEN/ LAKSVÅG FANA/ YTREBYGDA ARNA/ ÅSANE BERGENHUS/ ÅRSTAD Forvaltningsenheten Forvaltningsenheten Forvaltningsenheten Forvaltningsenheten Tjenester for hab/rehab Tjenester for hab/rehab Tjenester for hab/rehab Tjenester for hab/rehab Barne- og fam.tjenester Barne- og fam.tjenester Barne- og fam.tjenester Barne- og fam.tjenester Barnevern Barnevern Barnevern Barnevern Hjemmebaserte tjenester Hjemmebaserte tjenester Hjemmebaserte tjenester Hjemmebaserte tjenester Botjenester til utvhemmede Botjenester til utvh. -

Stadnamn I Luster Kommune I Indre Sogn

Universitetet i Bergen Institutt for lingvistiske, litterære og estetiske studiar Stadnamn i Luster kommune i Indre Sogn Ein prototypebasert analyse av namnelandskapet i eit vestlandsk jordbruksdistrikt Samuele Mascetti NOLISP350 Mastergradsoppgåve i nordisk Vår 2017 Føreord Å skriva denne masteravhandlinga har vore for meg fyrst og fremst ei personleg fordjuping i tankegangen og levemåten typiske for både staden eg kjem frå og staden eg har valt å bu på: Alpane og Vestlandet. Eg er fødd og oppvaksen i ei lita fjellbygd ved Comosjøen i nordlege Lombardia fylke i Nord-Italia, ved grensa mot Sveits. Det alpine innsjølandskapet har mykje til felles med fjordlandskapet på Vestlandet: Høge, bratte fjell som stuper i vatnet, djupe og grisgrendte dalar, dårlege vegar og mykje, mykje regn. Kulturlandskapet er òg nokso likt: Jordbruket var lenge hovudnæringa i det alpine området, og stølinga spelte ei sentral rolle i den tradisjonelle gardsordninga. Det norditalienske setersystemet er nesten identisk med det vestlandske og dei fleste bruka har to setrar: Heimesetra (kalla munt, ‘fjell’ på lombardisk), som ligg om lag mellom 600 og 1400 moh. og er nytta vår og haust, og langsetra (kalla alp, ‘høgfjell’ på lombardisk), som ligg om lag mellom 1500 og 2500 moh. og er nytta om sumaren. Dei fleste bygdene ligg mellom 200 og 600 moh., so begge setrar er utstyrde med stølshus, sidan dei ligg fleire timar gonge frå heimehusa. Som gutunge var eg mang ein sumar på selet hans bestefar og fekk oppleva den gamle stølstradisjonen, som diverre alt då var døyande: Dei fleste gardsbrukarane la driftene ned pga. den uoverkomelege økonomiske sentraliseringa i jordbrukspolitikken til EU-landa, som trengte dei småe produsentane ut til fordel for dei store industrialiserte bruka i låglandet kring storbyane. -

Ancient Magic and Modern Accessories: Developments in the Omamori Phenomenon

Western Michigan University ScholarWorks at WMU Master's Theses Graduate College 8-2015 Ancient Magic and Modern Accessories: Developments in the Omamori Phenomenon Eric Teixeira Mendes Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wmich.edu/masters_theses Part of the Asian History Commons, Buddhist Studies Commons, and the History of Religions of Eastern Origins Commons Recommended Citation Mendes, Eric Teixeira, "Ancient Magic and Modern Accessories: Developments in the Omamori Phenomenon" (2015). Master's Theses. 626. https://scholarworks.wmich.edu/masters_theses/626 This Masters Thesis-Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate College at ScholarWorks at WMU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Master's Theses by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at WMU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ANCIENT MAGIC AND MODERN ACCESSORIES: DEVELOPMENTS IN THE OMAMORI PHENOMENON by Eric Teixeira Mendes A thesis submitted to the Graduate College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Comparative Religion Western Michigan University August 2015 Thesis Committee: Stephen Covell, Ph.D., Chair LouAnn Wurst, Ph.D. Brian C. Wilson, Ph.D. ANCIENT MAGIC AND MODERN ACCESSORIES: DEVELOPMENTS IN THE OMAMORI PHENOMENON Eric Teixeira Mendes, M.A. Western Michigan University, 2015 This thesis offers an examination of modern Japanese amulets, called omamori, distributed by Buddhist temples and Shinto shrines throughout Japan. As amulets, these objects are meant to be carried by a person at all times in which they wish to receive the benefits that an omamori is said to offer. In modern times, in addition to being a religious object, these amulets have become accessories for cell-phones, bags, purses, and automobiles. -

Architecture Program Report for 2012 NAAB Visit for Continuing Accreditation

Harvard Graduate School of Design Department of Architecture Architecture Program Report for 2012 NAAB Visit for Continuing Accreditation Master of Architecture Undergraduate degree outside of Architecture + 105 graduate credit hours Related pre-professional degree + 75 graduate credit hours Year of the Previous Visit: 2006 Current Term of Accreditation: At the July 2006 meeting of the National Architectural Accrediting Board (NAAB), the board reviewed the Visiting Team Report for the Harvard University Department of Architecture. As a result, the professional architecture program: Master of Architecture was formally granted a six-year term of accreditation. The accreditation term is effective January 1, 2006. The program is scheduled for its next accreditation visit in 2012. Submitted to: The National Architectural Accrediting Board Date: 14 September 2011 Harvard Graduate School of Design Architecture Program Report September 2011 Program Administrator: Jen Swartout Phone: 617.496.1234 Email: [email protected] Chief administrator for the academic unit in which the program is located (e.g., dean or department chair): Preston Scott Cohen, Chair, Department of Architecture Phone: 617.496.5826 Email: [email protected] Chief Academic Officer of the Institution: Mohsen Mostafavi, Dean Phone: 617.495.4364 Email: [email protected] President of the Institution: Drew Faust Phone: 617.495.1502 Email: [email protected] Individual submitting the Architecture Program Report: Mark Mulligan, Director, Master in Architecture Degree Program Adjunct Associate Professor of Architecture Phone: 617.496.4412 Email: [email protected] Name of individual to whom questions should be directed: Jen Swartout, Program Coordinator Phone: 617.496.1234 Email: [email protected] 2 Harvard Graduate School of Design Architecture Program Report September 2011 Table of Contents Section Page Part One. -

Rehabilitering Utenfor Institusjon Innsatsteam

Hvordan ta kontakt: Du kan selv ta kontakt med oss, eller du kan be helsepersonell l (institusjon, fastlegen, ergo- f Tjenesten tilbys dagtid mandag til fysioterapitjenesten, hjemmesy- Rehabilitering t kepleien) å henvise til oss. Tje- fredag. Det er ingen egenandel på nesten er organisert under Ergo- utenfor tjenesten Rehabilitering utenfor in- og Fysioterapitjenestene i Ber- institusjon gen Kommune: stitusjon i henhold til lov om kom- munale helse og omsorgstjeneste. Arna / Åsane (base Åstveit): 53 03 51 50 / 40 90 64 57 Bergenhus /Årstad (base Engen): Den som søker helsehjelp kan på- 55 56 93 66 / 94 50 38 14 Innsatsteam - klage avgjørelsen dersom det gis av- Fana / Ytrebygda (base Nesttun): slag eller dersom det menes at rettig- 55 56 18 70 / 94 50 79 60 rehabilitering hetene ikke er oppfylt. Klage sendes Fyllingsdalen/ Laksevåg (base Fyllingsdalen): 53 03 30 09 / 94 50 38 15 til Helsetilsynet i fylket og klagen skal være skriftlig (jfr. Lov om pasi- E-post: entrettigheter § 7-2). innsatsteam-rehabilitering@ bergen.kommune.no Rehabilitering utenfor institusjon Oppfølgingsperioden er tverrfaglig og Et ønske om endring innen funksjon, Innsatsteam-rehabilitering gir tjenes- aktivitet og/ eller deltakelse kan være ter til deg som nylig eller innen siste individuelt tilpasset og kan inneholde: utgangspunkt for rehabilitering. år, har fått påvist et hjerneslag eller Kartlegging av funksjon en lett/moderat traumatisk hodeska- Dine mål står sentralt i rehabilite- de. Målrettet trening ringsforløpet. Innsatsteam-rehabilitering er et tverr- Veiledning til egentrening og aktivitet faglig team bestående av fysiotera- peut, ergoterapeut og sykepleier. Samtale, mestring og motivasjon Egentrening og egeninnsats er viktig Oppfølgingen fra Innsatsteam– reha- for å få en god rehabiliteringsprosess. -

Jotunheimen National Park

Jotunheimen National Park Photo: Øivind Haug Map and information Jotunheimen Welcome to the National Park National Parks in Norway Welcome to Jotunheimen An alpine landscape of high mountains, snow and glaciers whichever way you turn. This is how it feels to be on top of Galdhøpiggen: You know that at this moment in time you are at the highest point in Norway with firm ground under your feet. What you see around you are the highest mountains of Northern Europe. An alpine landscape of high mountains, deciduous forests and high waterfalls. snow and glaciers whichever way you The public footpath that winds its way turn. This is how it feels to be on top up the valley crosses over the wildly of Galdhøpiggen: You know that at this cascading Utla river many times on its moment in time you are at the highest way down the valley. point in Norway with firm ground under your feet. What you see around Can you see yourself on top of one you are the highest mountains of of the sharpest ridges? Mountain Northern Europe. climbing in Jotunheimen is as popular today as when the English started to Jotunheimen covers an area from explore these mountains during the the west country landscape of high, 1800s and many are still following sharp ridged peaks in Hurrungane, the in the footsteps of Slingsby and the most distinctive peaks, to the eastern other pioneers. country landscape of large valleys and mountain lakes. Do you dream about the jerk of the fishing rod when a trout bites? Do you The emerald green Gjende is the dream of escaping to the mountains in queen of the lakes. -

Folklore and Earthquakes: Native American Oral Traditions from Cascadia Compared with Written Traditions from Japan

See discussions, stats, and author profiles for this publication at: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/249551808 Folklore and earthquakes: Native American oral traditions from Cascadia compared with written traditions from Japan Article in Geological Society London Special Publications · January 2007 DOI: 10.1144/GSL.SP.2007.273.01.07 CITATIONS READS 20 5,081 12 authors, including: R. S. Ludwin Deborah Carver University of Washington Seattle University of Alaska Anchorage 18 PUBLICATIONS 261 CITATIONS 2 PUBLICATIONS 95 CITATIONS SEE PROFILE SEE PROFILE Robert J. Losey Coll Thrush University of Alberta University of British Columbia - Vancouver 103 PUBLICATIONS 1,174 CITATIONS 20 PUBLICATIONS 137 CITATIONS SEE PROFILE SEE PROFILE Some of the authors of this publication are also working on these related projects: Cheekye Fan - Squamish Floodplain Interactions View project Peace River area radiocarbon database View project All content following this page was uploaded by John J. Clague on 07 June 2016. The user has requested enhancement of the downloaded file. Downloaded from http://sp.lyellcollection.org/ at Simon Fraser University on June 6, 2016 Folklore and earthquakes: Native American oral traditions from Cascadia compared with written traditions from Japan RUTH S. LUDWIN 1 & GREGORY J. SMITS 2 IDepartment of Earth and Space Sciences, University of Washington, Box 351310, Seattle, WA 98195-1310, USA (e-mail: [email protected]) 2Department of Histoo' and Program in Religious Studies, 108 Weaver Building, The Pennsylvania State UniversiO', Universio' Park, PA 16802, USA With Contributions from D. CARVER 3, K. JAMES 4, C. JONIENTZ-TRISLER 5, A. D. MCMILLAN 6, R. LOSEY 7, R. -

A POPULAR DICTIONARY of Shinto

A POPULAR DICTIONARY OF Shinto A POPULAR DICTIONARY OF Shinto BRIAN BOCKING Curzon First published by Curzon Press 15 The Quadrant, Richmond Surrey, TW9 1BP This edition published in the Taylor & Francis e-Library, 2005. “To purchase your own copy of this or any of Taylor & Francis or Routledge’s collection of thousands of eBooks please go to http://www.ebookstore.tandf.co.uk/.” Copyright © 1995 by Brian Bocking Revised edition 1997 Cover photograph by Sharon Hoogstraten Cover design by Kim Bartko All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher. British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library ISBN 0-203-98627-X Master e-book ISBN ISBN 0-7007-1051-5 (Print Edition) To Shelagh INTRODUCTION How to use this dictionary A Popular Dictionary of Shintō lists in alphabetical order more than a thousand terms relating to Shintō. Almost all are Japanese terms. The dictionary can be used in the ordinary way if the Shintō term you want to look up is already in Japanese (e.g. kami rather than ‘deity’) and has a main entry in the dictionary. If, as is very likely, the concept or word you want is in English such as ‘pollution’, ‘children’, ‘shrine’, etc., or perhaps a place-name like ‘Kyōto’ or ‘Akita’ which does not have a main entry, then consult the comprehensive Thematic Index of English and Japanese terms at the end of the Dictionary first. -

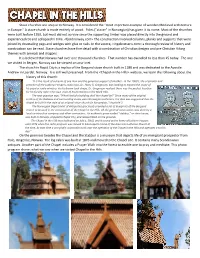

Stave Churches Are Unique to Norway. It Is Considered the "Most Important Example of Wooden Medieval Architecture in Europe." a Stave Church Is Made Entirely of Wood

Stave churches are unique to Norway. It is considered the "most important example of wooden Medieval architecture in Europe." A stave church is made entirely of wood. Poles ("staver" in Norwegian) has given it its name. Most of the churches were built before 1350, but most did not survive since the supporting timber was placed directly into the ground and experienced rot and collapsed in time. <fjordnorway.com> The construction involved columns, planks and supports that were joined by dovetailing pegs and wedges with glue or nails. In the source, <ingebretsens.com> a thorough review of history and construction can be read. Stave churches have fine detail with a combination of Christian designs and pre‐Christian Viking themes with animals and dragons. It is believed that Norway had over one thousand churches. That number has dwindled to less than 25 today. The one we visited in Bergen, Norway can be viewed on acuri.net. The church in Rapid City is a replica of the Borgund stave church built in 1180 and was dedicated to the Apostle Andrew in Laerdal, Norway. It is still well preserved. From the <Chapel‐in the‐Hills> website, we learn the following about the history of this church: "It is the result of a dream of one man and the generous support of another...In the 1960's, the originator and preacher of the Lutheran Vespers radio hour, Dr. Harry R. Gregerson, was looking to expand the scope of his popular radio ministry. As his dream took shape, Dr. Gregerson realized there was the perfect location for his facility right in his own state of South Dakota in the Black Hills.