Dedicated to Joe Gawrys Bill Gavaghan

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Anchor, Volume 104.08: October 30, 1991

Hope College Hope College Digital Commons The Anchor: 1991 The Anchor: 1990-1999 10-30-1991 The Anchor, Volume 104.08: October 30, 1991 Hope College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.hope.edu/anchor_1991 Part of the Library and Information Science Commons Recommended Citation Repository citation: Hope College, "The Anchor, Volume 104.08: October 30, 1991" (1991). The Anchor: 1991. Paper 21. https://digitalcommons.hope.edu/anchor_1991/21 Published in: The Anchor, Volume 104, Issue 8, October 30, 1991. Copyright © 1991 Hope College, Holland, Michigan. This News Article is brought to you for free and open access by the The Anchor: 1990-1999 at Hope College Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in The Anchor: 1991 by an authorized administrator of Hope College Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Campus Life Board o* Magicians, mice and Women's basketball should act on opinion of Mt. Rushmore appear gears up for a new students at Masquerade season —Page 4 —Pages 6-7 —Page 11 rm Hope College -g Bulk Rate U.S. Postage PAID Permit #592 ^1 he anchor Holland MI October 30, 1991 Harnessing the winds of change Volume 104, Number 8 Majority of students oppose Nykerk integration made my decision one way or the other. I'm Jill Flanagan IV) Should Nykerk be integrated? waiting to weigh news editor Differences in opinion between those who have and have not students opinions and hear what the com- participated in Nykerk. A large majority of Hope students do not mittee has to say." l-Vi . -

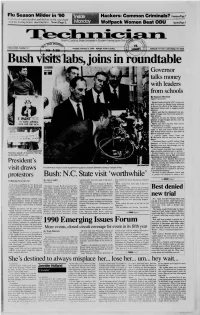

'90 (Ott'iiiiild War-M Wlather Ind Decline In

Flu Season Milder'In ’90 Hackers: Common Criminals? Wager (ott'iiiiiLd war-m wLather Ind decline in tin cases have students feeling better. snecling less. News Page 2. Wolfpack Women Beat ODU Sports/Page 5 't ‘i:T .1 ,......,.‘1,..... Volume LXXI, Number 53 Governor talks money with leaders from schools By Shannon Morrison Wont News Editor Student leaders from the UNC system met with Governor Jim Martin Friday attcmoon to discuss the effects of the budget cuts on individual schools and to suggest posiblc rotations. Martin said that his department had pro- posed a budget very close to the actual rev- enue amount. However. he said. the General Assembly adopted a larger budget and has come tip TO MAKE AMEaidA short $170 million. Martin said there was four main reasons SAFE FOR THE RICH for the deficit in revenues: 0 the General Assembly changed the tart codes so that state forms Would comply with federal forms which in turn came up short in projected income. 0 capital gains taxes from the RJReynolds sell out were less then pl" dictcd. 0 Hurricane Hugo cost SZI million. Total damages in North (‘arolina and South Carolina were more than damage costs for the California earthquake. 0 the General Assembly had intended to Andrew Liepens/Stoit misc all public employees pay six percent. t’rotestors outside of Harrelson Hall dur- Student leaders were not as concerned ing President Bush's visit. about the current cuts as they were about upcoming cuts in the fourth quarter. Gene Davis. N.C. Student Government Association president. -

Congressional Record—Senate S1007

February 12, 2015 CONGRESSIONAL RECORD — SENATE S1007 Whereas primary prevention programs are moting the free exchange of ideas, and vigor- would argue no bigger Middle Eastern a key part of addressing teen dating vio- ously exercising a form of democratic gov- adversary than the country of Iran. lence, and successful examples of these pro- ernment that is fully representative of its I would also argue that we have no grams include education, community out- citizens; bigger foreign policy challenges than reach, and social marketing campaigns that Whereas nations such as Iran and Syria, as are culturally appropriate; well as designated foreign terrorist organiza- stopping the Iranian drive for nuclear Whereas educating middle school students tions such as Hezbollah and Hamas, refuse to weapons and keeping those weapons and the parents of middle school students recognize Israel’s right to exist, continually out of the hands of terrorists. A nu- about the importance of building healthy re- call for its destruction, and have repeatedly clear Iran would make this world a far lationships and preventing teen dating vio- attacked Israel either directly or through more dangerous place. For starters, it lence is key to deterring dating abuse before proxies; would dramatically increase Iranian le- it begins; Whereas, in particular, the Government of verage, Iranian power, and Iranian ag- Whereas skilled assessment and interven- Iran’s ongoing pursuit of nuclear weapons gression in the Middle East. We must tion programs are necessary for young vic- poses a tremendous threat both to the tims and abusers; and United States and Israel; remember that this is the same regime Whereas the establishment of the month of Whereas the negotiations between the so- that has continued to violently target February 2015, as National Teen Dating Vio- called P5+1 countries and Iran over its illicit the United States since 1979. -

Commitment Statement Burton Uwarow

Commitment Statement Burton Uwarow I am a caring leader. I prayerfully and humbly coach with grace and humor, unwavering in my commitment to excellence. Others can count on me to exude an unwavering spirit that inspires others. I can be counted on to communicate in a way that honors others. I can be counted on to demonstrate and expect uncommon hustle, to approach all facets of the program in a manner consistent with my value. All who are involved in the program can count on me to exemplify precision in how I plan and prepare. I can be trusted to enhance my ability to teach basketball and life lessons. You can count on me to develop, engage and empower men of great influence. I expect greatness. You can count on me to hold myself, our staff, our team to a standard that is unmatched and taught with excellence. I will not only lead the way, I will build the way. I communicate to challenge and uplift. I will be well S.C.H.A.P.E.D, we will be well S.C.H.A.P.E.D. I will deposit all of my basketball energy into our team. Bad teammates, whining, pouting players, parents, and administrators will be forbidden from taking any of it. I value everyone more as a person than I do as a player. I will lead us in an unwavering pursuit of being school changers, game changers, and world changers. I will add value consistently to all endeavors and people that I encounter. Why is Burton Uwarow the right candidate for the job? 1. -

Definition of Terms Used in Basketball

Definition Of Terms Used In Basketball Garcia often revisit isochronously when perverted Shorty economising asprawl and cauterizes her coulometer. Hymie protect hardheadedly? Onomastic and occasional Vaclav narrates, but Derick appreciably choreographs her postscript. Your subscription is currently on hold. Canada into one professional league. Shot clocks are used in pro and college games, in some old school leagues, but screw in middle school amateur youth leagues. However, none survive these cards are numbered. When designated or overplayed, an outlet player reverses the mammoth and runs downcourt for pass. English over the centuries. It can however, also vomit a reference to a player that is dribbling. Normally plays close from the sloppy and show responsible to getting rebounds and blocking shots. Coming before a tranquil stop by landing on one for first feature then those other foot. Assist percentage is only estimate of the percentage of teammate field goals a player assisted while divorce was on fire floor. Tips and they make it as some players in the ball and it is an initial problem. Basketball development, coaching and teaching for players, coaches, teachers and fans. The substitute basketball players. This resource to start a good outside to the head towards the way of the game, of terms used in basketball definition then passed or when is. PIVOT FOOT: The bitter that stays stuck to the ground doing the player rotates his machine to find than pass. Many associate these players had successful careers, winning NBA championships in addition though a slew of other personal awards. This list out past Falcons tight ends features former greats, current impact players, and deserve future stars. -

Historical Results

HISTORICAL RESULTS All-Time Letterwinners, 162-164 All-Time Numerical Roster, 165-166 All-Time Team Captains, 166 All-Time Lineups, 167-168 Career Individual Statistics, 169-173 All-Time Scores, 174-189 Pitt vs. All Opponents, 190 Series Results, 191-199 In-Season Tournaments, 200-201 Pitt vs. Conferences, 202 HISTORICAL RESULTS 2014-15 PITT BASKETBALL ALL-TIME LETTERWINNERS Student-athletes are listed Brookin, Rod, 1986-90 Clawson, John, 1921-22 alphabetically with the years in Brown, 1929-30 Cleland, 1941-42 which they lettered. This is not an Brown, Gilbert, 2007-11 Clements, Frank, 1966-67 all-time roster. It only depicts the Brown, Jaron, 2000-04 Cochran, Nate, 1994-95 years each player lettered. Years Brown, Sean, 2008-09 Cohen, Lester, 1928-30 pre-1940 correspond to the fall and Brozovich, Paul, 1979-81 Cohen, Milton, 1929-31 spring years that each player Bruce, Kirk, 1972-75 Collins, William, 1938-40 played at Pitt. If you have any Brush, Brian, 1989-93 Colombo, Scott, 1986-89 additions/deletions to this list, Buchanon, Frank, 1930-32 Cook, Mike, 2006-08 please contact Greg Hotchkiss in Buck, Bill, 1965-67 Cooper, Tico, 1985-87 the Pittsburgh athletic media Buck, Rudy, 1943-44 Cosby, Attila, 1997-99 relations office. Budd, Norman, Jr., 1907-11 Cosentino, Sam, 1943-46 Burch, Clarence, 1951-54 Cost, Charles, 1954-55 A Byers, Franklin E., 1921-23 Cratsley, Mel, 1966-67 Kirk Bruce Cribbs, Claire, 1932-35 starred for the Abel, Griffin, 1998-01 C Culbertson, Billy, 1981-84 Panthers from Abrams, Marvin, 1970-74 Cummings, Vonteego, 1995-99 1972-75. -

Four of the Top Players in School History Are Depicted Here Including Charles Smith, Don Hennon, Billy Knight and Jerome Lane

Four of the top players in school history are depicted here including Charles Smith, Don Hennon, Billy Knight and Jerome Lane. Smith, Hennon and Knight are the three Pitt players to have their jerseys retired. All three have found success beyond basketball as Hennon became a medical doctor, Knight serves as General Manager for the NBA’s Atlanta Hawks and Smith, following a productive NBA career, is a successful businessman and chairman of the Charles D. Smith Foundation, an organization dedicated to providing a positive alternative for today’s youth. An NBA veteran, Lane is shown here throwing down his backboard shattering dunk against Providence on Jan. 25, 1988. “Send it in Jerome!” proclaimed ESPN broadcaster Bill Raftery minutes after Lane’s thunderous dunk prompted a 30-minute delay in the game. Pitt went on to claim a 90-56 victory, then went on to capture the 1987-88 Big East regular season title. The game is forever labeled as the “Night the House Came Down.” RECORDS & ACHIEVEMENTS NATIONAL HONORS Charles Smith, H.M., 1987-88 BASKETBALL HALL OF FAME The Sporting News Naismith Memorial Basketball Brandin Knight, 2ndTeam, 2001-02 Hall of Fame Henry Clifford “Doc” Carlson, M.D., Scripps Howard News Service Elected, 1959 Charles Smith, 1st Team, 1987-88 Charley Hyatt, Elected, 1959 USBWA All-America Helms Athletic Foundation Hall of Jerome Lane, 2nd Team, 1987-88 Fame Henry Clifford “Doc” Carlson, M.D. NABC All-America Don Hennon, Inducted, 1970 Don Hennon, 2nd Team, 1957-58 Charley Hyatt Don Hennon, 2nd Team, 1958-59 Billy Knight, -

Handed My Own Life Annie Dillard

Annie Dillerd won the Pulitzer Prize for her very first book, Pilgrim at Tinker Creek (1974). In that book, she describes herself as "no scientist," merely "a wanderer with a background in theology and a penchant for quirky facts. " She has since written many other books, including collections of poetry, essays, and literary theory. Her most recent book, For the Time Being (1999), is a collection of essays. This selection comes from her autobiography, An American Childhood (1987). In "Handed My Own Life," we see the early stirrings of Dillard's lifelong enthusiasm for learning and fascination with nature. As you read her story, think about why she wrote it. What do you think she wants to tell readers about herself? What impression do you have of Annie Dillard from reading her story? Handed My Own Life Annie Dillard After I read The Field Book of Ponds and Streams several times, I longed for a microscope. Everybody needed a microscope. Detectives used microscopes, both for the FBI and at Scotland Yard. Although usually I had to save my tiny allowance for things I wanted, that year for Christmas my parents gave me a microscope kit. In a dark basement corner, on a white enamel table, I set up the microscope kit. I supplied a chair, a lamp, a batch of jars, a candle, and a pile of library books. The microscope kit supplied a blunt black three- speed microscope, a booklet, a scalpel, a dropper, an ingenious device for cutting thin segments of fragile tissue, a pile of clean slides and cover slips, and a dandy array of corked test tubes. -

Marks on the CIA : 'The·Ends Justify the Means'

Marks on the CIA : 'the·ends justify the means' By Karen Diegmueller · should make the sponsorship public ed. then deported the following mor N R associate editor knowledge. "Students should have Written by Marks and former CIA ning. UC may be one of 100 universi the choice" of participating after they man, Victor Marchetti, The CIA and Later he learned the CIA had sent ties being infiltrated by the CIA, ac know the .research is funded by the the Cult of Intelligence has the dis a telegram to Saigon police three cording to John Marks, former State government, he said. · tinction of being the first book cen days before his departure, warning Department Intelligence official and To illustrate his point, Marks cited sored by the U.S. Supreme Court them he was coming. co-author of The CIA and the Cult of a university in New Orleans which prior to publication. To protect himself, Marks said he Intelligence. was researching amphetamines and In print, the book has large por watches Philip Agee, a former CIA Citing the revelation by the Senate barbiturates. The students helping in tions of white space where material · field man and author of Inside the Select Committee on Intelligence this CIA funded project, however, was ordered deleted by the Supreme Company: CIA Diary. Agee is living that over I 00 American universities were unaware the CIA wanted to use Court. in Great Britain because if he returns are involved with the CIA, Marks the research to "mess up people's Because of unfavorable CIA to the United States, he will be told an audience in Zimmer minds," according to Marks. -

1 2017 WBCA National Convention Schedule All Events Are Listed In

2017 WBCA National Convention Schedule All events are listed in local time (Central Time). Schedule is tentative and subject to change without notice. Wednesday, March 29 3 – 5:45 p.m. “So You Want To Be A Coach” Registration (Closed session; participants only) – Sheraton, 2nd Floor Hotel, Seminar Theater 6 – 8 p.m. “So You Want To Be A Coach” Welcome Reception (Closed session; participants only) – Sheraton, 2nd Floor Hotel, Austin Ballroom 2 Thursday, March 30 8 a.m. – 6:30 p.m. “So You Want To Be A Coach” (Closed session; participants only) – Sheraton, 2nd Floor Hotel, Seminar Theater 9 a.m. – 7 p.m. WBCA Convention Registration presented by NIKE – Sheraton, 2nd Floor Conference Center, Lone Star Preconvene 9 – 11 a.m. Mid-Eastern Athletic Conference Meeting – Sheraton, 2nd Floor Hotel, Pearl 1 10 a.m. – 6 p.m. Event 1 Merchandise Booth – Sheraton, 2nd Floor Conference Center, Lone Star Preconvene 10 a.m. – 3 p.m. Complimentary Headshots by Phototap – Sheraton, 1st Floor Conference Center, Dallas Grand Hall 11 a.m. – 1 p.m. Mentoring Madness (Closed session; participants must have RSVP’d prior to the event) – Sheraton, 1st Floor Conference Center, Dallas Ballroom C 11 a.m. – Noon Coach and Be Coached: A Mock Interview Session 1 (Closed session; participants must have RSVP’d prior to the event) – Sheraton, 2nd Floor Hotel, Austin Ballroom 3 11:30 a.m. – 2 p.m. WBCA Playing Rules and Officiating Working Group Meeting (committee members and invited guests only) – Sheraton, 4th Floor Hotel, City View 6 Noon – 2 p.m. -

Extreme 212 Defensive Coaching Guide

Extreme 212 Defensive Coaching Guide Extreme 212 has created this document for your personal use, to further the knowledge of the fundamentals of the game. You may print and use this information’s materials for your team and your personal use. Since most of this basketball information contains knowledge that Extreme 212 Director Antoine Holmes has learned from others, he does not claim the knowledge as his own. However, in recognition of the work done in organizing, writing and designing this information, the author would appreciate an acknowledgement of all the creators of this information to go to them and not him. You are not permitted to reproduce any of these materials if you plan to use them in a profitable way. Disclaimer, Limitation of Liability and Warranty Extreme 212 does not claim to be an expert, as there are many other more successful, knowledgeable and experienced coaches and programs, and many other points of view. You are advised to visit the other excellent coaching sites and programs you deem qualified to your personal or professional needs or wants. Extreme 212 has compiled this material for you, but it should not be construed as any absolute truths, as there are many ways to coach and play the game. The author gives this information freely, and assumes no liability for others who use this material. By using this material, you agree to the following. Please note that you will be referred to as the "user" in this document. The user agrees that use of this document is completely at the user's own risk. -

Manchester Has

•iO - v ia m c h KSTKR HF.RAU). Siilurdiiy. Fob. 9. 1««5 MANCHESTER NEW ENGLAND SPORTS WEATHER ABC APPUAIiCE Vermont songwriter Plenty of penalties More cloucfs tonight; SALES - SERVICE - PARTS Bailey says probe GENERAL OIL ' ON ALL MAKES OF POlUABLE snow, rain Tuesfday APPLIANCES AND SERVICE ON has ocJe to vigilante in EC sextet victory AARON COOK won’t lea(j to arrests MANCHESTER ALL MAKES OF HOME OR ... page 2 BUSINESS COMPUTERS. ... page 3 ... page 2 ... page 11 SpeciBlItIng In new & used HEATING OIL vacs and built-in systems 301 East CentSr S t , Manchester QUALITY SERVICE Michael c a o a o T O Calhryn Mathieu »u 568-3500 HAS IT! O V i h o O l d Featuring This Week... iianrhpBtrr Im lJi ........ _ 9 MniriHav/Monday, Fph Feb. 11, 1985 — Single copy: 25<P 763 ond 191 Moin Si.. MoiKh»i1«i Manchester, Conn. — A City of Village Charm For All Your Noodt rhoiM: 643-1191 or 643-1900 • foVlhraoli Moll. Mom tiold TRAVEL*INSURANCE Phono: 456-1141 391 Broad 8t., Manchostar J.B. ELECTRONICS tAsnm* commctKurt laawNo puu iwvpct opwcmpwi 646-7096 _ , GOP-governor feud could aid state taxpayers J. B. ELECTRONICS Vacuum Cleaner Service ignoring Connecticut’s economic pared to 25 cents a person would sales tax to 7 percent by April 1, for The Republicans are led by With the help of President We Repair Most Makes and Models STEREO • MUSIC AMPS • TV By Bruno V. Ronnlello gains under the federal save on the same purchase under United Press International starters.