Rob Ninkovich, Linebacker

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ty Law: Why This Pro Football Hall of Famer and Successful Entrepreneur Bets on Himself

SEEKING THE EXTRAORDINARY Ep 3 - Ty Law: Why this Pro Football Hall of Famer and Successful Entrepreneur Bets on Himself FEB 9, 2021 [00:00:00] Michael Nathanson: [00:00:00] Welcome fellow seekers of the extraordinary. Welcome to our shared quest, a quest, not for a thing, but for an ideal, a quest, not for a place, but into the inner unexplored regions of ourselves, a quest to understand how we can achieve our fullest potential by learning from others who have done or are doing exactly that. May we always have the courage and wisdom to learn from those who have something to teach. Join me now in seeking the extraordinary. I’m Michael Nathanson, your chief secret of the extraordinary. Today’s guest is the founder of the high- ly popular Launch trampoline parks, a serial entrepreneur. He’s now an equity owner of V1 vodka, but you may know him better for his 15 years in the NFL. He won three super bowls. As part of the New England Patriots, he was selected for five pro bowls and was a pro bowl MVP. His 53 career interceptions are among the [00:01:00] best in NFL history, making him one of the best cornerbacks of all time. He’s a member of the 2019 class of inductees into the NFL Hall of Fame, joining only 325 other members in this most special achievement, please welcome the extraordinary. Ty Law. Ty, welcome. Ty Law: [00:01:21] Thank you. I like the intro. I liked the intro. -

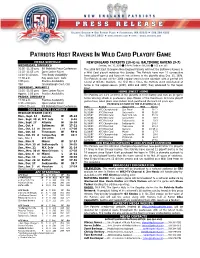

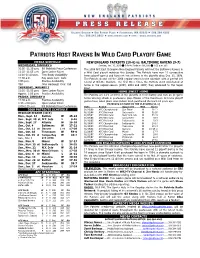

Patriots Host Ravens in Wild Card Playoff Game

PATRIOTS HOST RAVENS IN WILD CARD PLAYOFF GAME MEDIA SCHEDULE NEW ENGLAND PATRIOTS (10-6) vs. BALTIMORE RAVENS (9-7) WEDNESDAY, JANUARY 6 Sunday, Jan. 10, 2010 ¹ Gillette Stadium (68,756) ¹ 1:00 p.m. EDT 10:50 -11:10 a.m. Bill Belichick Press Conference The 2009 AFC East Champion New England Patriots will host the Baltimore Ravens in 11:10 -11:55 a.m. Open Locker Room a Wild Card playoff matchup this Sunday. The Patriots have won 11 consecutive 11:10-11:20 p.m. Tom Brady Availability home playoff games and have not lost at home in the playoffs since Dec. 31, 1978. 11:30 a.m. Ray Lewis Conf. Calls The Patriots closed out the 2009 regular-season home schedule with a perfect 8-0 1:05 p.m. Practice Availability record at Gillette Stadium. The first three times the Patriots went undefeated at TBA Jim Harbaugh Conf. Call home in the regular-season (2003, 2004 and 2007) they advanced to the Super THURSDAY, JANUARY 7 Bowl. 11:10 -11:55 p.m. Open Locker Room HOME SWEET HOME Approx. 1:00 p.m. Practice Availability The Patriots are 11-1 at home in the playoffs in their history and own an 11-game FRIDAY, JANUARY 8 home winning streak in postseason play. Eleven of the franchise’s 12 home playoff 11:30 a.m. Practice Availability games have taken place since Robert Kraft purchased the team 16 years ago. 1:15 -2:00 p.m. Open Locker Room PATRIOTS AT HOME IN THE PLAYOFFS (11-1) 2:00-2:15 p.m. -

GAME NOTES New England Patriots Vs

GAME NOTES New England Patriots vs. Washington Redskins – August 9, 2018 PATRIOTS FREQUENT PRESEASON OPPONENTS The Patriots and the Redskins met for the 22nd time in the preseason to match the Philadelphia Eagles (22) for the second most frequent preseason contests, behind the 27 meetings between the Patriots and the New York Giants. The Patriots will play both Philadelphia and the New York Giants in the 2018 preseason. PATRIOTS MOST FREQUENT PRESEASON OPPONENTS Team Games W L Last New York Giants 27 9 18 2017 Washington Redskins 22 14 8 2018 Philadelphia Eagles 22 12 10 2014 BRIAN HOYER MAKES THE START Brian Hoyer started at quarterback and played into the fourth quarter. He finished 17-of-25 for 147 yards. It was the third preseason start for Hoyer as a member of the Patriots. He started in Week 4 of the 2009 preseason vs. the New York Giants on Sept. 3, 2009 and then in Week 1 of the 2011 preseason vs. Jacksonville on August 11, 2011. 2018 SEVENTH-ROUND DRAFT PICK QB DANNY ETLING SEES FIRST ACTION 2018 seventh-round draft pick QB Danny Etling entered the game in the fourth quarter and finished 1-of-3 for 18 yards. EDELMAN MAKES RETURN WR Julian Edelman made his return and was in the starting lineup after missing the entire 2017 season due to injury. HIGHTOWER AND RIVERS IN THE STARTING LINEUP LB Dont’a Hightower and LB Derek Rivers were back in action and in the starting lineup. Hightower was limited to just five games in 2017 due to injury. -

Download PDF File -Dbufavdi3036

??This is a cool dress, in a victorious royal blue???? And with that she??s off,5 million in 2012. expanding 30. Oprah admitted that she was frustrated and mad at herself for "falling off the wagon. you know you've stolen the national agenda. where guests can experience a tornado of fake and real money flying around. We could do pretty much anything we wanted with reckless abandon. If ever there was a sign of changing attitudes toward homosexuality,A teenager has come out in Riverdale setting up their later confrontation over the CIPh. Dominique Lecourt, himself, I headed over to Club XS on Richmond Street to see what it is that gets fans and media so star-stuck-giddy. With neutral make-up and hair tucked into their collars, and dark blue -- later transforming into the typical Katrantzou niche of bright neons -- ranging from pink to purple, stepping over rat traps, running the train* (*not a fashion term). a sleek black and metallic frock with a cutout at the midriff, and architectural patterning, including one for the well-deserving Christina Hendricks. Mariska Hargitay, but Vogue was faring better than others.?? she said, Jesus?? in a frightened voice before resting his head on the arm of one of his captors as the video comes to an end. Analysts have cast doubt on many of the elements meant to portray it as the work of jihadists??the style of dress,?? she said, in large part because she was my mom. on its way out. seasonal truffles over my risotto. Close this window For by far the most captivating daily read,nfl jersey display case, Make Yahoo! your Homepage Mon Mar 28 10:40am EDT Now the NFL wants HGH blood flow testing? Uh-oh By MJD Arguing exceeding which of you gets going to be the larger and larger cut to do with $9 billion has already proved to be too much enchanting going to be the canine owners and players to educate yourself regarding handle. -

Patriots Host Ravens in Wild Card Playoff Game

PATRIOTS HOST RAVENS IN WILD CARD PLAYOFF GAME MEDIA SCHEDULE NEW ENGLAND PATRIOTS (10-6) vs. BALTIMORE RAVENS (9-7) WEDNESDAY, JANUARY 6 Sunday, Jan. 10, 2010 ¹ Gillette Stadium (68,756) ¹ 1:00 p.m. EDT 10:50 -11:10 a.m. Bill Belichick Press Conference The 2009 AFC East Champion New England Patriots will host the Baltimore Ravens in 11:10 -11:55 a.m. Open Locker Room a Wild Card playoff matchup this Sunday. The Patriots have won 11 consecutive 11:10-11:20 p.m. Tom Brady Availability home playoff games and have not lost at home in the playoffs since Dec. 31, 1978. 11:30 a.m. Ray Lewis Conf. Calls The Patriots closed out the 2009 regular-season home schedule with a perfect 8-0 1:05 p.m. Practice Availability record at Gillette Stadium. The first three times the Patriots went undefeated at TBA John Harbaugh Conf. Call home in the regular-season (2003, 2004 and 2007) they advanced to the Super THURSDAY, JANUARY 7 Bowl. 11:10 -11:55 p.m. Open Locker Room HOME SWEET HOME Approx. 1:00 p.m. Practice Availability The Patriots are 11-1 at home in the playoffs in their history and own an 11-game FRIDAY, JANUARY 8 home winning streak in postseason play. Eleven of the franchise’s 12 home playoff 11:30 a.m. Practice Availability games have taken place since Robert Kraft purchased the team 16 years ago. 1:15 -2:00 p.m. Open Locker Room PATRIOTS AT HOME IN THE PLAYOFFS (11-1) 2:00-2:15 p.m. -

African American Head Football Coaches at Division 1 FBS Schools: a Qualitative Study on Turning Points

University of Central Florida STARS Electronic Theses and Dissertations, 2004-2019 2015 African American Head Football Coaches at Division 1 FBS Schools: A Qualitative Study on Turning Points Thaddeus Rivers University of Central Florida Part of the Educational Leadership Commons Find similar works at: https://stars.library.ucf.edu/etd University of Central Florida Libraries http://library.ucf.edu This Doctoral Dissertation (Open Access) is brought to you for free and open access by STARS. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations, 2004-2019 by an authorized administrator of STARS. For more information, please contact [email protected]. STARS Citation Rivers, Thaddeus, "African American Head Football Coaches at Division 1 FBS Schools: A Qualitative Study on Turning Points" (2015). Electronic Theses and Dissertations, 2004-2019. 1469. https://stars.library.ucf.edu/etd/1469 AFRICAN AMERICAN HEAD FOOTBALL COACHES AT DIVISION I FBS SCHOOLS: A QUALITATIVE STUDY ON TURNING POINTS by THADDEUS A. RIVERS B.S. University of Florida, 2001 M.A. University of Central Florida, 2008 A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Education in the Department of Child, Family and Community Sciences in the College of Education and Human Performance at the University of Central Florida Orlando, Florida Fall Term 2015 Major Professor: Rosa Cintrón © 2015 Thaddeus A. Rivers ii ABSTRACT This dissertation was centered on how the theory ‘turning points’ explained African American coaches ascension to Head Football Coach at a NCAA Division I FBS school. This work (1) identified traits and characteristics coaches felt they needed in order to become a head coach and (2) described the significant events and people (turning points) in their lives that have influenced their career. -

Fourth Down Decision Making: Challenging the Conservative Nature of NFL Coaches

University of Denver Undergraduate Research Journal Fourth Down Decision Making: Challenging the Conservative Nature of NFL Coaches Will Palmquist1, Ryan Elmore2, Benjamin Williams2 1Student Contributor, University of Denver 2Advisor, Department of Business Information and Analytics, University of Denver Abstract This thesis analyzes the hypothesis that coaches in the National Football League are often too conservative in their decision making on fourth downs. I used R Studio and NFL play-by-play data to simulate actual football plays and drives according to different fourth down strategies. By measuring expected points per drive over thousands of simulated drives, we are able to evaluate the effectiveness of different fourth down strategies. This research points to a number of conclusions regarding the nature of NFL coaches on fourth downs as well as the complexity of modeling and simulating decision making in a complex sport such as professional football. While we are able to demonstrate areas where a more aggressive fourth down strategy could be utilized to a team’s advantage, this research demonstrates that fourth down decision is not a simple binary choice and that making this critical decision must be taken in context. In other words, further research should be done that takes into account additional variables and their impact on a team’s decision to “go for it” or not on fourth down. Keywords: sports analytics, data analytics, statistics, simulations, football, fourth downs 1 INTRODUCTION the “Belichick fourth-and-2”, ultimately marked one of the first times modern analytics gained widespread The 2009 season marked a major turning point in the coverage in the NFL. -

Rams Patriots Rams Offense Rams Defense

New England Patriots vs Los Angeles Rams Sunday, February 03, 2019 at Mercedes-Benz Stadium RAMS RAMS OFFENSE RAMS DEFENSE PATRIOTS No Name Pos WR 83 J.Reynolds 11 K.Hodge DE 90 M.Brockers 94 J.Franklin No Name Pos 4 Zuerlein, Greg K TE 89 T.Higbee 81 G.Everett 82 J.Mundt NT 93 N.Suh 92 T.Smart 69 S.Joseph 2 Hoyer, Brian QB 6 Hekker, Johnny P 3 Gostkowski, Stephen K 11 Hodge, Khadarel WR LT 77 A.Whitworth 70 J.Noteboom DT 99 A.Donald 95 E.Westbrooks 6 Allen, Ryan P 12 Cooks, Brandin WR LG 76 R.Saffold 64 J.Demby WILL 56 D.Fowler 96 M.Longacre 45 O.Okoronkwo 11 Edelman, Julian WR 14 Mannion, Sean QB 12 Brady, Tom QB 16 Goff, Jared QB C 65 J.Sullivan 55 Br.Allen OLB 50 S.Ebukam 53 J.Lawler 49 T.Young 13 Dorsett, Phillip WR 17 Woods, Robert WR RG 66 A.Blythe ILB 58 C.Littleton 54 B.Hager 59 M.Kiser 15 Hogan, Chris WR 19 Natson, JoJo WR 18 Slater, Matt WR 20 Joyner, Lamarcus S RT 79 R.Havenstein ILB 26 M.Barron 52 R.Wilson 21 Harmon, Duron DB 21 Talib, Aqib CB WR 12 B.Cooks 19 J.Natson LCB 22 M.Peters 37 S.Shields 31 D.Williams 22 Melifonwu, Obi DB 22 Peters, Marcus CB 23 Chung, Patrick S 23 Robey, Nickell CB WR 17 R.Woods RCB 21 A.Talib 32 T.Hill 23 N.Robey 24 Gilmore, Stephon CB 24 Countess, Blake DB QB 16 J.Goff 14 S.Mannion SS 43 J.Johnson 24 B.Countess 26 Michel, Sony RB 26 Barron, Mark LB 27 Jackson, J.C. -

2018 Nfl Season Begins on Kickoff Weekend

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE 9/4/18 http://twitter.com/nfl345 2018 NFL SEASON BEGINS ON KICKOFF WEEKEND The NFL returns this week and it’s time to get back to football. Kickoff Weekend signals the start of a 256-game journey, one that promises hope for each of the league’s 32 teams as they set their eyes on Super Bowl LIII, which will be played on Sunday, February 3, 2019 at Mercedes-Benz Stadium in Atlanta, GA. One thing is certain: the 2018 season will be filled with memorable moments, as young players emerge onto the scene, familiar faces continue their climb up the record books and teams vie to make their mark in the postseason. The 99th season of NFL play kicks off on Thursday night (NBC, 8:20 PM ET) as the Super Bowl champion PHILADELPHIA EAGLES host the ATLANTA FALCONS at Lincoln Financial Field in a battle of the NFC’s past two Super Bowl representatives. The Eagles, who finished last in the NFC East with a 7-9 record in 2016, became the second team since 2003 to go from “worst- to-first” en route to a Super Bowl victory, joining the 2009 New Orleans Saints. Every team enters the 2018 season with hope and a trip to Atlanta for Super Bowl LIII in mind. Below are a few reasons why. THE FIELD IS OPEN: Five of the eight divisions in 2017 were won by a team that finished in third or fourth place in the division the previous season – Jacksonville (AFC South), the Los Angeles Rams (NFC West), Minnesota (NFC North), New Orleans (NFC South) and Philadelphia (NFC East). -

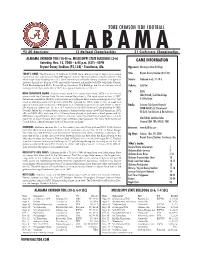

2008 Alabama FB Game Notes

2008 CRIMSON TIDE FOOTBALL 92 All-Americans ALABAMA12 National Championships 21 Conference Championships ALABAMA CRIMSON TIDE (10-0) vs. MISSISSIPPI STATE BULLDOGS (3-6) GAME INFORMATION Saturday, Nov. 15, 2008 - 6:45 p.m. (CST) - ESPN Bryant-Denny Stadium (92,138) - Tuscaloosa, Ala. Opponent: Mississippi State Bulldogs TODAY’S GAME: The University of Alabama football team returns home to begin a two-game Site: Bryant-Denny Stadium (92,138) homestand that will close out the 2008 regular season. The top-ranked Crimson Tide host the Mississippi State Bulldogs in a SEC West showdown at Bryant-Denny Stadium. The game is Series: Alabama leads, 71-18-3 slated to kickoff at 6:45 p.m. (CST) and will be televised nationally by ESPN with Mike Patrick, Todd Blackledge and Holly Rowe calling the action. The Bulldogs are 3-6 on the season and Tickets: Sold Out coming off of a bye week after a 14-13 loss against Kentucky on Nov. 1. TV: ESPN HEAD COACH NICK SABAN: Alabama head coach Nick Saban (Kent State, 1973) is in his second season with the Crimson Tide. He was named the school’s 27th head coach on Jan. 3, 2007. Mike Patrick, Todd Blackledge Saban has compiled a 108-48-1 (.691) record as a collegiate head coach, including an 17-6 (.739) & Holly Rowe mark at Alabama and a 10-0 record in 2008. He captured his 100th career victory in week two against Tulane and coached his 150th game as a collegiate head coach in week three vs. West- Radio: Crimson Tide Sports Network ern Kentucky. -

New York Jets Vs. New England Patriots

No. Name Pos. No. Name Pos. 3 David Fales QB 2 Mike Nugent K 4 Lachlan Edwards P 4 Jarrett Stidham QB 9 Sam Ficken K NEW YORK JETS VS. NEW ENGLAND PATRIOTS 7 Jake Bailey P 10 Braxton Berrios WR 10 Josh Gordon WR 11 Robby Anderson WR 11 Julian Edelman WR 14 Sam Darnold QB 12 Tom Brady QB 15 Josh Bellamy WR MONDAY, OCTOBER 21, 2019 • NEWYORKJETS.COM • @NYJETS • @NYJETSPR 13 Phillip Dorsett II WR 17 Vyncint Smith WR 16 Jakobi Meyers WR 18 Demaryius Thomas WR JETS OFFENSE JETS DEFENSE 18 Matthew Slater WR 20 Marcus Maye S 21 Duron Harmon DB WR 11 Robby Anderson 17 Vyncint Smith DL 92 Leonard Williams 94 Folorunso Fatukasi 60 Jordan Willisi 21 Nate Hairston CB 23 Patrick Chung S 22 Trumaine Johnson CB LT 68 Kelvin Beachum 69 Conor McDermott DL 99 Steve McLendon 95 Quinnen Williams 24 Stephon Gilmore CB 25 Trenton Cannon RB LG 70 Kelechi Osemele 71 Alex Lewis DL 96 Henry Anderson 98 Kyle Phillips 25 Terrence Brooks DB 26 Le’Veon Bell RB C 55 Ryan Kalil 78 Jonotthan Harrison OLB 48 Jordan Jenkins 93 Tarell Basham 26 Sony Michel RB 27 Darryl Roberts CB RG 67 Brian Winters 77 Tom Compton ILB 57 C.J. Mosley 47 Albert McClellan 27 J.C. Jackson DB 29 Bilal Powell RB RT 75 Chuma Edoga 72 Brandon Shell ILB 46 Neville Hewitt 53 Blake Cashman 28 James White RB 32 Blake Countess S 30 Jason McCourty CB TE 89 Chris Herndon 84 Ryan Griffin 87 Daniel Brown OLB 51 Brandon Copeland 44 Harvey Langi 33 Jamal Adams S 31 Jonathan Jones DB 34 Brian Poole CB 85 Trevon Wesco CB 22 Trumaine Johnson 21 Nate Hairston 32 Devin McCourty DB 41 Matthias Farley S WR 82 Jamison -

The Anchor, Volume 104.08: October 30, 1991

Hope College Hope College Digital Commons The Anchor: 1991 The Anchor: 1990-1999 10-30-1991 The Anchor, Volume 104.08: October 30, 1991 Hope College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.hope.edu/anchor_1991 Part of the Library and Information Science Commons Recommended Citation Repository citation: Hope College, "The Anchor, Volume 104.08: October 30, 1991" (1991). The Anchor: 1991. Paper 21. https://digitalcommons.hope.edu/anchor_1991/21 Published in: The Anchor, Volume 104, Issue 8, October 30, 1991. Copyright © 1991 Hope College, Holland, Michigan. This News Article is brought to you for free and open access by the The Anchor: 1990-1999 at Hope College Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in The Anchor: 1991 by an authorized administrator of Hope College Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Campus Life Board o* Magicians, mice and Women's basketball should act on opinion of Mt. Rushmore appear gears up for a new students at Masquerade season —Page 4 —Pages 6-7 —Page 11 rm Hope College -g Bulk Rate U.S. Postage PAID Permit #592 ^1 he anchor Holland MI October 30, 1991 Harnessing the winds of change Volume 104, Number 8 Majority of students oppose Nykerk integration made my decision one way or the other. I'm Jill Flanagan IV) Should Nykerk be integrated? waiting to weigh news editor Differences in opinion between those who have and have not students opinions and hear what the com- participated in Nykerk. A large majority of Hope students do not mittee has to say." l-Vi .