INFORMATION to USERS This Manuscrit Has Been Reproduced

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

View Exhibition Brochure

1 Renée Cox (Jamaica, 1960; lives & works in New York) “Redcoat,” from Queen Nanny of the Maroons series, 2004 Color digital inket print on watercolor paper, AP 1, 76 x 44 in. (193 x 111.8 cm) Courtesy of the artist Caribbean: Crossroads of the World, organized This exhibition is organized into six themes by El Museo del Barrio in collaboration with the that consider the objects from various cultural, Queens Museum of Art and The Studio Museum in geographic, historical and visual standpoints: Harlem, explores the complexity of the Caribbean Shades of History, Land of the Outlaw, Patriot region, from the Haitian Revolution (1791–1804) to Acts, Counterpoints, Kingdoms of this World and the present. The culmination of nearly a decade Fluid Motions. of collaborative research and scholarship, this exhibition gathers objects that highlight more than At The Studio Museum in Harlem, Shades of two hundred years of history, art and visual culture History explores how artists have perceived from the Caribbean basin and its diaspora. the significance of race and its relevance to the social development, history and culture of the Caribbean: Crossroads engages the rich history of Caribbean, beginning with the pivotal Haitian the Caribbean and its transatlantic cultures. The Revolution. Land of the Outlaw features works broad range of themes examined in this multi- of art that examine dual perceptions of the venue project draws attention to diverse views Caribbean—as both a utopic place of pleasure and of the contemporary Caribbean, and sheds new a land of lawlessness—and investigate historical light on the encounters and exchanges among and contemporary interpretations of the “outlaw.” the countries and territories comprising the New World. -

Artist of the People's World (Pt 1) Publ¡Shed: Sunday I Novembor 18,2007

Iamaica Gleaner Online Artist of the people's world (Pt 1) publ¡shed: Sunday I Novembor 18,2007 Cooper Alexander Cooper is an artist living and working at Cooper's Hill, St. Andrew. Today, he drscusse s his work with Jonathan Greenland, executive director of the National Gallery. You are famous as a painter of the Jamaican people, is this important to you? I do like the grassroots. I like to draw my people in their settings: Their settings in terms of the homes that they live in, the lifestyles that they lead and their attire. When I started I I found this the most interesting material and l'm still doing it. I like to portray my people in their natural setting, for example, a Jamaican market scene is always a high- ' , colourful visual spectacle. For the past three years I have been painting old Jamaican churches. How do you go about making your paintings? Most of the subjects are outdoors and look to be painted from life. Well, I would say they are painted from life in the sense they are based on observation at the scene. Some of these events like carnival and festival I am always present at them. I can stand to one side and observe the colour and the pageantry and then almost paint from memory. A good example is one of the first works I did - it won the first prize at the lnstitute of Jamaica in 1962. lt is a painting of Port Royal and now it is at the NationalGallery. I got 100 pounds for it. -

Visual Art As a Window for Studying the Caribbean Compiled and Introduced by Peter B

Visual Art as a Window for Studying the Caribbean Compiled and introduced by Peter B. Jordens Curaçao: August 26, 2012 The present document is a compilation of 20 reviews and 36 images1 of the visual-art exhiBition Caribbean: Crossroads of the World that is Being held Between June 12, 2012 and January 6, 2013 at three cooperating museums in New York City, USA. The remarkaBle fact that Crossroads has (to date) merited no fewer than 20 fairly formal art reviews in various US newspapers and on art weBlogs can Be explained By the terms of praise in which the reviews descriBe the exhiBition: “likely the most expansive art event of the summer (p. 20 of this compilation), the summer’s BlockBuster exhiBition (p. 21), the big art event of the summer in New York (p. 15), immense (p. 34), Big, varied (p. 21), diverse (p. 10), comprehensive (p. 20), amBitious (pp. 19, 21, 22, 33, 34), impressive (p. 21), remarkaBle (p. 21), not one to miss (p. 30), wholly different and very rewarding (p. 33), satisfying (pp. 21, 33), visual feast (p. 25), Bonanza (p. 25), rare triumph (p. 21), significant (p. 13), unprecedented (p. 10), groundbreaking (pp. 13, 23), a game changer (p. 13), a landmark exhiBition (p. 13), will define all other suBsequent CariBBean surveys for years to come (p. 22).” Crossroads is the most recent tangiBle expression of an increase in interest in and recognition of CariBBean art in the CariBBean diaspora, in particular the USA and to less extent Western Europe. This increase is likely the confluence of such factors as: (1) the consolidation of CariBBean immigrant communities in North America and Europe, (2) the creative originality of artists of CariBBean heritage, (3) these artists’ greater moBility and presence in the diaspora in the context of gloBalization, especially transnational migration, travel and information flows,2 and (4) the politics of multiculturalism and of postcolonial studies. -

Art of a New Nation

Pgs062-066_ART 05/19/06 5:34 PM Page 63 f art would people create while throwing off f What kind o ive hundred years of slavery, colonialism, and oppression? Jamaicans only began to discover their English father and a Jamaican mother, true culture in 1922, dawn of the Jamai- Edna had married Norman Washington can Art Movement, when they began to Manley in 1921. depict real people living real lives in real Her sculptures captured the rhythm Jdignity, for the first time. Neither the of the markets and the songs of the Taino natives, nor the Spanish who con- plantations. They displayed the phy- quered them, had left much in the way "Negro Aroused" ver. iii 1982, siques and gestures of real Jamaicans. from a private collection exhibited at of art. Jamaica’s planters, leaders of an Gallery, Edna Manley College With heads up in hope, or down in English colony from 1670 to 1962, did CofAGE the Visual and Performing Arts, anger, works like “Negro Aroused” commission some art from Europe. So with the Edna Manley Foundation, (1935), “The Prophet” (1936), and “To- churches, graveyards, and squares host- morrow” (1939) became icons of the February 27 to March 2, 2006. ed fine neoclassical sculptures. Trav- new social order. Other pioneers of the elogues displayed genteel English watercolors. Hobbyists Jamaican Art Movement included Karl Parboosingh, made picturesque landscapes and florals. Albert Huie, Carl Abrahams, Barrington Watson, Mallica But where were all the bright colors and traditional “Kapo” Reynolds, Michael Lester, and Cecil Baugh. wood carvings of the Africans? Even though 95 percent of Extrovert Karl Parboosingh, born 1923 in St. -

Haptic Tactility: How Design Processes Can Remediate Identities Past and Present

Haptic tactility: how design processes can remediate identities past and present Marcia Swaby A thesis in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Philosophy School of Art and Design Faculty of Art and Design January 2018 I PLEASE TYPE THE UNIVERSITY OF NEW SOUTH WALES Thesis/Dissertation Sheet I Surname or Family name: Swaby First name: Marcia Other name/s: Annette I Abbreviation for degree as given in the University calendar: MPhil School:.School of Art and Design Faculty: Faculty of Art and Design Title: Haptic tactility: how design processes can remediate I identities past and present Abstract 350 words maximum: (PLEASE TYPE) There is little known of the prehistory of the Caribbean and the Taino people- the firstinhabitants of the region. From the island of Jamaica, significantTaino artefacts are currently held in storage in the British Museum. This project explores how one 'brings to life' their identities, and how this may engage with contemporary jewellery and object making practices. The project has wider implications forminority communities- particularly for those subjugated by western imperialism from the end of the fifteenth Century to the late nineteenth century and, arguably, formany up to and including the various independence movements fo11owingWorld War Two. This period has contributed to the many factors that create an invisibility of black artists and their contributions to a wider art history. In addressing the significant problem of 'invisibility', the aim of this thesis is to investigate how contemporary jewellery and object making processes, methods and outcomes can act as catalysts forre-integrating fragmented and dispersed relationships. -

Jamaica Journal Index with Abstracts 1990 – 2008

Jamaica Journal Index with abstracts 1990 – 2008 Compiled by : Cheryl Kean and Karlene Robinson University of the West Indies, Mona. Preface Coverage The purpose of this index is to articles that have been published in the Jamaica Journal since 1997. It covers the following issues:- Vol 23 no. 1 (1990) to Volume 31 nos. 1 & 2 (2008). All articles, book reviews, poems and short stories are included in the index. Arrangement The index is arranged in two sections. The first section is a general List of abstracts arranged alphabetically by the first named author or title. This is a list of all articles that are included in this index with an abstract provided for each article with the exception of book reviews, stories and poems. All entries are numbered. The second section is an Author and keyword list. The number that is listed beside each term corresponds to the number that is given to each entry in the general list of abstracts. Library of Congress Subject Headings were used to generate the list of keywords for all the entries in the index with the exception of a few cases where no appropriate terms existed to capture the subject material. List of Abstrtacts 1. The Altamont DaCosta Institute. Jamaica Journal 2000; 27(1):Back cover. Abstract: This article presents a brief biography of Altamont DaCosta, former mayor and custos of Kingston. The Institute was the former dwelling house of Mr. DaCosta and was willed to the people of Jamaica in 1935. 2. The Calabash tree (crescentia cujete). Jamaica Journal 2008; 31(1-2):Back cover. -

Jamaica National Heritage Trust (JNHT), Jamaica Archive and Gordon, Ms

AtlAs of CulturAl HeritAge AND iNfrAstruCture of tHe Americas JAMAICA luis Alberto moreno President Board of trustees Honourable General Coordinator liliana melo de sada olivia grange m. P. Alfonso Castellanos Ribot ChairPerson of the Board Minister ● ● ● national liaison Trustees mr. robert martin Marcela Diez teresa Aguirre lanari de Bulgheroni PerManent seCretary ● sandra Arosemena de Parra ● national teaM Adriana Cisneros de griffin senator Warren Newby Desmin Sutherland-Leslie (Coordinator) gonzalo Córdoba mallarino Halcyee Anderson Andrés faucher Minister of state marcello Hallake Shemicka Crawford enrique V. iglesias ● Christine martínez V-s de Holzer ProGraMMers eric l. motley, PhD A Alfonso Flores (Coordinator) rodolfo Paiz Andrade Eduardo González López marina ramírez steinvorth directories Alba M. Denisse Morales Álvarez Julia salvi ● Ana maría sosa de Brillembourg Diego de la torre editorial Coordination ● Alfonso Castellanos Ribot sari Bermúdez ● Ceo editorial desiGn raúl Jaime Zorrilla Juan Arroyo and Luz María Zamitiz dePuty Ceo Editorial Sestante, S.A. de C.V. Atlas of Cultural Heritage and Printed and made in Mexico Infrastructure of the Americas: Jamaica isBN (colection:) 978-607-00-4877-7 Primera edición, 2011 isBN (Jamaica Atlas) 978-607-00-4910-1 first edition, 2011 © C. r. inter American Culture and Development foundation, ministry of Youth, sports and Culture, Jamaica. Acknowledgements Institute of Jamaica on behalf of the Cultural Atlas team, we would like to thank the following organisations provided fundamental information the following persons were instrumental in the creation minister olivia grange, m.P. minister of Youth, sports and Culture and support that enabled the publication of the Atlas: of the Atlas: for partnering with the inter-American Cultural foundation (iCDf) to facilitate the creation of the Atlas of Cultural Heritage institute of Jamaica (IOJ), National library of Jamaica (NlJ), ms. -

Summer 2021 7/24/2021-7/25/2021 LOT # LOT

Summer 2021 7/24/2021-7/25/2021 LOT # LOT # 1 Chinese 14K Gold Figural Dragon on Stand 3 8 pcs. Meiji Japanese Silver Tea Set, Iris Decorat Chinese 14K gold (tested) figural dragon, Asian Export Sterling Silver Tea Service with depicted standing with raised head. Fitted with high relief iris decorations, eight (8) pieces. a conforming hardwood stand. 2" H x 3 1/2" W. ARTHUR & BOND, STERLING, and 73.3 grams. Provenance: the estate of Camille YOKOHAMA stamped to underside of bases. Gift, Nashville, Tennessee by descent from Sara Includes a kettle on stand, coffee pot, teapot, tea Joan Wilde (1923-2014), Colorado Springs, caddy, covered sugar bowl, creamer, CO. Mrs. Wilde and her husband, Lt. Col. Adna double-handled waste bowl, and a pair of sugar Godfrey Wilde (1920-2008) traveled tongs. Also includes an International Silver extensively throughout Asia as part of his career Company burner. Pieces ranging in size from 9 as an officer with the U.S. Army. Condition: 3/4" H x 8" W to 1" H x 5" L. 116.60 total troy Overall very good condition. 2,400.00 - ounces. Meiji Period. Provenance: private 2,600.00 Chattanooga collection. Consignor's Quantity: 1 grandparents acquired this set and the Arthur & Bond teacups also in this auction (see lot #3) while traveling in Asia in the early 1900s. Condition: All items in overall very good condition. Handles slightly loose to teapots. 2 Asian Export Silver Cocktail Set, incl. Shaker, Be 4,800.00 - 5,200.00 Japanese export silver cocktail set, comprised of Quantity: 1 one (1) shaker, eight (8) beaker style liqueur cups, and one (1) tray with wooden center insert and silver rim, 14 items total. -

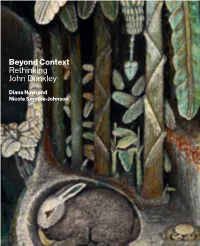

Beyond Context Rethinking John Dunkley

Beyond Context Rethinking John Dunkley Diana Nawi and Nicole Smythe-Johnson Nawi and Smythe-Johnson 10 Portrait of John Dunkley, n.d., Kingston John Dunkley: Neither Day nor the subject not only of art historical analyses, but also within Night has two central objec- the narrative of a broader nationalist cultural agenda, he left no tives. First, to locate and bring written or oral first-person record. The narrative of his “discov- together, for the first time since ery” by English art historian Hender Delves Molesworth and his 1976—and for the first time close association with Edna and Norman Manley (particularly ever in the United States—a the former) positions him in the orbit of the political inner circle substantial selection of works of his period. Dunkley is often portrayed as a mentee under the by the Jamaican artist John influence of these important figures, among others, and encour- Dunkley. Only by seeing these aged and exposed to art history and exhibition opportunities by works together may we under- them.1 However, it is also recorded that Dunkley rejected offers stand Dunkley’s particular and to study with Edna Manley, and Molesworth thought better than precise visual language. to interfere with the artist’s technique—evidence of Dunkley’s autonomy and his belief in his unique vision.2 An equally significant goal of the exhibition, and especially In his essay, Boxer indexes a palpable anxiety around questions of this accompanying catalogue, is to contextualize Dunkley in of Jamaican identity in the 1930s—whether it would come into its his historical moment. -

Ebony G Patterson 2012 CV

Ebony G. Patterson (b.1981, Kingston. Jamaica) Education 2000‐2004 Edna Manley College for the Visual and Performing Arts Honors Diploma in Painting 2004‐2006 Sam Fox College of Art and Design, Washington University in St. Louis Printmaking/ Drawing , MFA Awards , Grants, Fellowships and Scholarships 2012 Mugrave Award , Bronze Medal in the Arts, Institute of Jamaica 2011 Rex Nettleford Fellowship for Cultural Studies An annual award awarded by the Rhodes Trust in Britain to member of the British Commonwealth residing in the Caribbean .The award provides funding to the fellow to realize a proposed project along with funding for Travel. The award is 10,000 GBP for the project and 2,000GBP for Travel. The award has been in existence for five years. Patterson is the first artist to receive the award. Small Axe Inc and Andy Warhol Foundation for the Art Grant Grant was provided to develop the ‘of 72’ Project. Young Alumni award of Distinction, Washington University in St. Louis, St. Louis, MO 2010 Honorary Mention for the Aaron Mattalon Award, National Gallery of Jamaica, Kingston Jamaica College of Fine Arts Travel Fellowship, University of Kentucky, Lexington, KY ‐Fellowship in support of installation project at the 2010 National Biennial at the National Gallery of Jamaica, Kingston Jamaica. 2009 College of Fine Arts Travel Fellowship , University of Kentucky, Lexington, KY ‐Fellowship is in support of an installation project at the first, ‘Ghetto Biennale’, in Port‐ Au‐Prince , Haiti 2008 Invited Artist for the Jamaica Biennial, National -

Brown, Everald CV

210 eleventh avenue, ste 201 new york, ny 10001 t 212 226 3768 f 212 226 0155 CAVIN-MORRIS GALLERY e [email protected] www.cavinmorris.com EVERALD BROWN (born 1917 in Clarendon, Jamaica; died 2003 in Brooklyn,! NY) A carpenter by trade, Brown began painting and carving in the late 1960’s while living in Kingston. At this time Brown, who was a self-ordained priest of a sect related to the Ethiopian Orthodox Church, was inspired by a vision to decorate a small church he had built. In addition to adorning the church with his paintings, he also carved ceremonial objects for it. These first works were very well received not only by his own congregation, but by other visitors. This encouraged Brown to continue painting and carving. He began participating in exhibitions and in the early 1970’s received several awards for his work. Because of the close connection between Brown’s artistic and spiritual life, his imagery drew heavily upon his spiritual experiences (including his interest in Rastafarianism), and his visions. In the early 1970’s Brown left Kingston to move to the country with his family. They settled in the remote district of Murray Mountain, the hills near St. Ann. Here on a limestone hill, named Meditation Heights, Brown built a house. The early years on Murray Mountain were especially productive and Brown produced many works, including the first of his highly decorative musical instruments (the drums, dove harps and star banjoes). Since then Brown has continued to live and work in his private sanctuary on Murray Mountain, inspired by nature and his mystical !visions. -

2-SA16 Thompson

“Black Skin, Blue Eyes”: Visualizing Blackness in Jamaican Art, 1922‐1944 Krista A. Thompson From the opposite end of the white world a magical Negro culture was hailing me. Negro sculpture! I began to fl ush with pride. Was this our salvation? —Frantz Fanon, Black Skin, White Masks I think that when any country is struggling out of colonial rule—and this is a political battle as well as a human rights endeavour, this struggle is almost the sole concern of the artist until this freedom has been achieved. So that the struggle for freedom was the concern of all the artists of those days . .: the values, the recognition of the image—our image—as a people and a country played a tremendous part in the art movement of the early days. —Edna Manley, “Th e Fine Arts” n the 1940s, as artist Edna Manley walked around an art exhibition fi lled with work by black Jamaican schoolchildren, she confronted several curious images. A student had created familiar enough pictures of local market women with “bandanas and the Itucked up skirt at the back,” yet had depicted the crayoned female fi gures as white, with blond hair and blue eyes. Manley recalled some decades later that it was an experience Small Axe 16, September 2004: pp. 1–31 ISSN 0799-0537 Downloaded from http://read.dukeupress.edu/small-axe/article-pdf/8/2/1/925980/2-sa16+thompson+(1-31).pdf by guest on 30 September 2021 that she “never got over.” “I learnt so much from it. Th ey were dressed absolutely correctly as market women and yet they had blond hair and blue eyes.