Music Is Power: Nueva Cancion’S Push for an Indigenous Identity

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Flutes, Festivities, and Fragmented Tradition: a Study of the Meaning of Music in Otavalo

Western Michigan University ScholarWorks at WMU Master's Theses Graduate College 4-2012 Flutes, Festivities, and Fragmented Tradition: A Study of the Meaning of Music in Otavalo Brenna C. Halpin Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wmich.edu/masters_theses Part of the Ethnomusicology Commons Recommended Citation Halpin, Brenna C., "Flutes, Festivities, and Fragmented Tradition: A Study of the Meaning of Music in Otavalo" (2012). Master's Theses. 50. https://scholarworks.wmich.edu/masters_theses/50 This Masters Thesis-Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate College at ScholarWorks at WMU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Master's Theses by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at WMU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. (/AV%\ C FLUTES, FESTIVITIES, AND FRAGMENTED TRADITION: A STUDY OF THE MEANING OF MUSIC IN OTAVALO by: Brenna C. Halpin A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty ofThe Graduate College in partial fulfillment ofthe requirements for the Degree ofMaster ofArts School ofMusic Advisor: Matthew Steel, Ph.D. Western Michigan University Kalamazoo, Michigan April 2012 THE GRADUATE COLLEGE WESTERN MICHIGAN UNIVERSITY KALAMAZOO, MICHIGAN Date February 29th, 2012 WE HEREBY APPROVE THE THESIS SUBMITTED BY Brenna C. Halpin ENTITLED Flutes, Festivities, and Fragmented Tradition: A Study of the Meaning of Music in Otavalo AS PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE Master of Arts DEGREE OF _rf (7,-0 School of Music (Department) Matthew Steel, Ph.D. Thesis Committee Chair Music (Program) Martha Councell-Vargas, D.M.A. Thesis Committee Member Ann Miles, Ph.D. Thesis Committee Member APPROVED Date .,hp\ Too* Dean of The Graduate College FLUTES, FESTIVITIES, AND FRAGMENTED TRADITION: A STUDY OF THE MEANING OF MUSIC IN OTAVALO Brenna C. -

WORKSHOP: Around the World in 30 Instruments Educator’S Guide [email protected]

WORKSHOP: Around The World In 30 Instruments Educator’s Guide www.4shillingsshort.com [email protected] AROUND THE WORLD IN 30 INSTRUMENTS A MULTI-CULTURAL EDUCATIONAL CONCERT for ALL AGES Four Shillings Short are the husband-wife duo of Aodh Og O’Tuama, from Cork, Ireland and Christy Martin, from San Diego, California. We have been touring in the United States and Ireland since 1997. We are multi-instrumentalists and vocalists who play a variety of musical styles on over 30 instruments from around the World. Around the World in 30 Instruments is a multi-cultural educational concert presenting Traditional music from Ireland, Scotland, England, Medieval & Renaissance Europe, the Americas and India on a variety of musical instruments including hammered & mountain dulcimer, mandolin, mandola, bouzouki, Medieval and Renaissance woodwinds, recorders, tinwhistles, banjo, North Indian Sitar, Medieval Psaltery, the Andean Charango, Irish Bodhran, African Doumbek, Spoons and vocals. Our program lasts 1 to 2 hours and is tailored to fit the audience and specific music educational curriculum where appropriate. We have performed for libraries, schools & museums all around the country and have presented in individual classrooms, full school assemblies, auditoriums and community rooms as well as smaller more intimate settings. During the program we introduce each instrument, talk about its history, introduce musical concepts and follow with a demonstration in the form of a song or an instrumental piece. Our main objective is to create an opportunity to expand people’s understanding of music through direct expe- rience of traditional folk and world music. ABOUT THE MUSICIANS: Aodh Og O’Tuama grew up in a family of poets, musicians and writers. -

Violeta Parra, Después De Vivir Un Siglo

En el documental Violeta más viva que nunca, el poeta Gonzalo Rojas llama a Violeta la estrella mayor de Chile, lo más grande, la síntesis perfecta. Esta elocuente descripción habla del sitial privilegiado que en la actualidad, por fin, ocupa Violeta Parra en nuestro país, después de muchos años injustos en los que su obra fue reconocida en el extranjero y prácticamente ignorada en Chile. Hoy, reconocemos a Violeta como la creadora que hizo de lo popular una expre- sión vanguardista, llena de potencia e identidad, pero también como un talento universal, singular y, quizás, irrepetible. Violeta fue una mujer que logró articular en su arte corrientes divergentes, obligándonos a tomar conciencia sobre la diversidad territorial y cultural del país que, además de valorar sus saberes originarios, emplea sus recursos para pavimentar un camino hacia la comprensión y valoración de lo otro. Para ello, tendió un puente entre lo campesino y lo urbano, asumiendo las antiguas tradi- ciones instaladas en el mundo campesino, pero también, haciendo fluir y trans- formando un patrimonio cultural en diálogo con una conciencia crítica. Además, construyó un puente con el futuro, con las generaciones posteriores a ella, y también las actuales, que reconocen en Violeta Parra el canto valiente e irreve- rente que los conecta con su palabra, sus composiciones y su música. Pero Violeta no se limitó a narrar costumbres y comunicar una filosofía, sino que también se preocupó de exponer, reflexionar y debatir sobre la situación política y social de la época que le tocó vivir, desarrollando una conciencia crítica, fruto de su profundo compromiso social. -

The Sex Pistols: Punk Rock As Protest Rhetoric

UNLV Retrospective Theses & Dissertations 1-1-2002 The Sex Pistols: Punk rock as protest rhetoric Cari Elaine Byers University of Nevada, Las Vegas Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalscholarship.unlv.edu/rtds Repository Citation Byers, Cari Elaine, "The Sex Pistols: Punk rock as protest rhetoric" (2002). UNLV Retrospective Theses & Dissertations. 1423. http://dx.doi.org/10.25669/yfq8-0mgs This Thesis is protected by copyright and/or related rights. It has been brought to you by Digital Scholarship@UNLV with permission from the rights-holder(s). You are free to use this Thesis in any way that is permitted by the copyright and related rights legislation that applies to your use. For other uses you need to obtain permission from the rights-holder(s) directly, unless additional rights are indicated by a Creative Commons license in the record and/ or on the work itself. This Thesis has been accepted for inclusion in UNLV Retrospective Theses & Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Digital Scholarship@UNLV. For more information, please contact [email protected]. INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. -

Violeta-Parra.Pdf

Tres discos autorales Juan Pablo González Fernando Carrasco Juan Antonio Sánchez Editores En el año del centenario de una de las máximas expresiones de la música chilena, Violeta Parra, surgió este proyecto que busca acercarnos a su creación desde su faceta de compositora y creadora de textos. La extensa obra de Violeta –que excede lo musical y llega a un plano más amplio del arte– se caracteriza en música por un profundo trabajo de recopilación primero y, posteriormente, por la creación original de numerosas canciones y temas instrumentales emblemáticos que –como Gracias a la Vida– han sido aquí por primera vez transcritas, en un ejercicio que busca llevar estas obras de carácter ya internacional, al universal lenguaje de la escritura musical y, con ello, ampliar el conoci- miento de su creación única y eterna. Violeta es parte de nuestra historia musical, y nuestra organización –que agrupa a los creadores del país y que tiene como misión proteger el trabajo que realizan por dar forma a nuestro repertorio y patrimonio– recibe y presenta con entusiasmo esta publicación, que esperamos sea un aporte en la valorización no sólo de la obra de esta gran autora, sino de nuestra música como un elemento único y vital de identidad y pertenencia. SOCIEDAD CHILENA DE AUTORES E INTÉRPRETES MUSICALES, SCD Violeta Parra Tres discos autorales Juan Pablo González, musicología Fernando Carrasco y Juan Antonio Sánchez, transcripción Osiel Vega, copistería digital Manuel García, prólogo Isabel Parra y Tita Parra, asesoría editorial Ediciones Universidad Alberto Hurtado Alameda 1869 - Santiago de Chile [email protected] - 56-228897726 www.uahurtado.cl Este libro fue sometido al sistema de referato ciego externo Impreso en Santiago de Chile en el mes de octubre de 2018 por C y C impresores ISBN libro impreso: 978-956-357-162-2 ISBN libro digital: 978-956-357-163-9 Coordinadora colección Música Daniela Fugellie Dirección editorial Alejandra Stevenson Valdés Editora ejecutiva Beatriz García-Huidobro Diseño de la colección y diagramación interior Gabriel Valdés E. -

The Global Charango

The Global Charango by Heather Horak A thesis submitted to the Faculty of Graduate and Postdoctoral Affairs in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Music and Culture Carleton University Ottawa, Ontario © 2020 Heather Horak i Abstract Has the charango, a folkloric instrument deeply rooted in South American contexts, “gone global”? If so, how has this impacted its music and meaning? The charango, a small and iconic guitar-like chordophone from Andes mountains areas, has circulated far beyond these homelands in the last fifty to seventy years. Yet it remains primarily tied to traditional and folkloric musics, despite its dispersion into new contexts. An important driver has been the international flow of pan-Andean music that had formative hubs in Central and Western Europe through transnational cosmopolitan processes in the 1970s and 1980s. Through ethnographies of twenty-eight diverse subjects living in European fields (in Austria, France, Belgium, Germany, Spain, Portugal, Switzerland, Croatia, and Iceland) I examine the dynamic intersections of the instrument in the contemporary musical and cultural lives of these Latin American and European players. Through their stories, I draw out the shifting discourses and projections of meaning that the charango has been given over time, including its real and imagined associations with indigineity from various positions. Initial chapters tie together relevant historical developments, discourses (including the “origins” debate) and vernacular associations as an informative backdrop to the collected ethnographies, which expose the fluidity of the instrument’s meaning that has been determined primarily by human proponents and their social (and political) processes. -

Violeta Parra Violeta Parra

1 Violeta Parra Violeta Parra Biografía Violeta del Carmen Parra Sandoval, folklorista, artista textil y pintora autodidacta. Nació en San Fabián de Alico, al interior de San Carlos en la provincia de Ñuble, Chile, el 4 de octubre de 1917 y falleció en Santiago el 5 de febrero de 1967. Su padre era profesor de música y su madre una campesina, modista de oficio, que gustaba del canto y la guitarra. Formaron una numerosa familia con nueve hijos cuya infancia transcurrió en el campo. A los nueve años Violeta Parra se inició en la guitarra y el canto y a los doce años compuso sus primeras canciones. Sus estudios primarios los realizó en las ciudades de Lautaro y Chillán. En 1932, se trasladó a vivir a Santiago e ingresó a estudiar a la Escuela Normal. En esa época ya componía boleros, corridos y tonadas, y trabajaba en quintas de recreo, bares, circos y pequeñas salas de barrio. En 1938, a los 21 años se casó con Luis Cereceda, trabajador ferroviario. De este matrimonio nacieron sus hijos Isabel y Ángel, con los cuales más tarde realizó gran parte de su trabajo artístico musical. A partir de 1952, impulsada por su hermano, el poeta Nicanor Parra, comenzó a recorrer diferentes zonas rurales, investigando y recopilando poesía y el canto popular de los más variados rincones del país, experiencia que sin duda repercutió en su sensibilidad artística, añadiendo elementos que luego plasmaría en sus obras plásticas. Entre los años 1952 y 1953 elaboró una síntesis de la cultura popular chilena e hizo emerger una tradición hasta entonces escondida, transformándose en una recuperadora y creadora de la cultura de América Latina. -

Program Notes

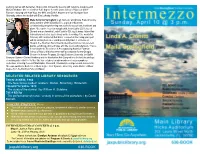

studying clarinet with her father, Nick Cionitti, followed by lessons with Valentine Anzalone and Michael Webster. She received her B.M. degree from the Crane School of Music at SUNY Potsdam, studying with Alan Woy. Her M.M. and D.M.A. degrees are from Michigan State University, where she studied with Elsa Ludewig-Verdehr. Maila Gutierrez Springfield is an instructor at Valdosta State University and a member of the Maharlika Trio, a group dedicated to commissioning and performing new works for saxophone, trombone and piano. She can be heard on saxophonist Joren Cain’s CD Voices of Dissent and on clarinetist Linda Cionitti’s CD Jag & Jersey. MusicWeb International selected Jag & Jersey as the recording of the month for February 2010 and noted that Maila “is superb in the taxing piano part with its striding bass lines and disjointed rhythms”. For Voices of Dissent, the American Record Guide describes Maila as “an excellent pianist, exhibiting solid technique and fine touch and pedal work." Twice- honored with the Excellence in Accompanying Award at Eastman School of Music, Maila has been staff accompanist for the Georgia Governor’s Honors Program, Georgia Southern University, the Buffet Crampon Summer Clarinet Academy and the Interlochen Arts Camp where she had the privilege of working with cellist Yo-Yo Ma. She has collaborated with members of major symphony orchestras, including those in Philadelphia, Cleveland, Cincinnati, Los Angeles and Jacksonville. She was awarded a Bachelor of Music degree from Syracuse University, and a Master of Music degree from the Eastman School of Music. SELECTED RELATED LIBRARY RESOURCES 780.92 A1N532, 1984 The New Grove modern masters : Bartók, Stravinsky, Hindemith 788.620712 S932s 1970 The study of the clarinet / by William H. -

Listado De Generos Autorizados.Xls

POR SUBGENERO LISTADO DE GENEROS AUTORIZADOS ACTUALIZADO AL 10 / 10 / 2006 SUBGENERO CODIGO GENERO AFRO 500 INTERNACIONAL AGOGO 594 INTERNACIONAL AIRES ESPAÑOLES 501 INTERNACIONAL ALBORADA 502 INTERNACIONAL ALEGRO VIVACE 455 SINFONICO Y CAMARA ANATEADA 627 FOLKLORE ANDANTE 400 SINFONICO Y CAMARA ARIA 401 SINFONICO Y CAMARA AUQUI AUQUI 633 FOLKLORE BAGUALA 300 FOLKLORE BAILECITO 301 FOLKLORE BAILE 402 INTERNACIONAL BAILES 302 FOLKLORE BAION 503 INTERNACIONAL BALADA 100 MELODICO BALLET 403 SINFONICO Y CAMARA BAMBUCO 595 INTERNACIONAL BARCAROLA 504 INTERNACIONAL BATUCADA 505 INTERNACIONAL BEAT 101 MELODICO BEGUINE 102 MELODICO BERCEUSE 404 SINFONICO Y CAMARA BLUES 103 MELODICO BOCETO 405 SINFONICO Y CAMARA BOGALOO 105 MELODICO BOLERO 104 MELODICO BOMBA 506 INTERNACIONAL BOOGIE BOOGIE 106 MELODICO BOSSA NOVA 507 INTERNACIONAL BOTECITO 508 INTERNACIONAL BULERIAS 509 INTERNACIONAL CACHACA 615 INTERNACIONAL CACHARPAYA 302 FOLKLORE CAJITA DE MUSICA 406 SINFONICO Y CAMARA CALIPSO 107 MELODICO CAMPERA 303 FOLKLORE CAN CAN 510 INTERNACIONAL CANCION 108 MELODICO CANCION DE CUNA 453 SINFONICO Y CAMARA CANCION FOLKLORICA 358 FOLKLORE Página 1 POR SUBGENERO LISTADO DE GENEROS AUTORIZADOS ACTUALIZADO AL 10 / 10 / 2006 SUBGENERO CODIGO GENERO CANCION INDIA 643 FOLKLORE CANCION INFANTIL 407 SINFONICO Y CAMARA CANCION MAPUCHE 642 FOLKLORE CANDOMBE 1 POPULAR CANON 408 SINFONICO Y CAMARA CANTATA 409 SINFONICO Y CAMARA CANTE JONDO 511 INTERNACIONAL CANZONETTA 109 MELODICO CAPRICCIO 410 SINFONICO Y CAMARA CARAMBA 304 FOLKLORE CARNAVAL 348 FOLKLORE CARNAVALITO -

HISPANIC MUSIC for BEGINNERS Terminology Hispanic Culture

HISPANIC MUSIC FOR BEGINNERS PETER KOLAR, World Library Publications Terminology Spanish vs. Hispanic; Latino, Latin-American, Spanish-speaking (El) español, (los) españoles, hispanos, latinos, latinoamericanos, habla-español, habla-hispana Hispanic culture • A melding of Spanish culture (from Spain) with that of the native Indian (maya, inca, aztec) Religion and faith • popular religiosity: día de los muertos (day of the dead), santería, being a guadalupano/a • “faith” as expession of nationalistic and cultural pride in addition to spirituality Diversity within Hispanic cultures Many regional, national, and cultural differences • Mexican (Southern, central, Northern, Eastern coastal) • Central America and South America — influence of Spanish, Portuguese • Caribbean — influence of African, Spanish, and indigenous cultures • Foods — as varied as the cultures and regions Spanish Language Basics • a, e, i, o, u — all pure vowels (pronounced ah, aey, ee, oh, oo) • single “r” vs. rolled “rr” (single r is pronouced like a d; double r = rolled) • “g” as “h” except before “u” • “v” pronounced as “b” (b like “burro” and v like “victor”) • “ll” and “y” as “j” (e.g. “yo” = “jo”) • the silent “h” • Elisions (spoken and sung) of vowels (e.g. Gloria a Dios, Padre Nuestro que estás, mi hijo) • Dipthongs pronounced as single syllables (e.g. Dios, Diego, comunión, eucaristía, tienda) • ch, ll, and rr considered one letter • Assigned gender to each noun • Stress: on first syllable in 2-syllable words (except if ending in “r,” “l,” or “d”) • Stress: on penultimate syllable in 3 or more syllables (except if ending in “r,” “l,” or “d”) Any word which doesn’t follow these stress rules carries an accent mark — é, á, í, ó, étc. -

Protest Music As Adult Education and Learning for Social Change: a Theorisation of a Public Pedagogy of Protest Music

Australian Journal of Adult Learning Volume 55, Number 3, November 2015 Protest music as adult education and learning for social change: a theorisation of a public pedagogy of protest music John Haycock Monash University Since the 1960’s, the transformative power of protest music has been shrouded in mythology. Sown by musical activists like Pete Seeger, who declared that protest music could “help to save the planet”, the seeds of this myth have since taken deep root in the popular imagination. While the mythology surrounding the relationship between protest music and social change has become pervasive and persistent, it has mostly evaded critical interrogation and significant theorisation. By both using the notion as a theoretical lens and adding to scholarship in the field, this article uncovers understandings of the public pedagogical dimensions of protest music, as it takes place as a radical practice and critical form of contemporary mass culture. In doing this, this article provides a theorisation of public pedagogy as it encapsulates protest music, and those who are conceptualised as the critical and radical public pedagogues who produce this mass cultural form. Keywords: public pedagogy; protest music; adult learning; education for social change 424 John Haycock Maybe it’s just the time of year Maybe it’s the time of man I don’t know who I am But life is for learning… Joni Mitchell, Woodstock, (1970), [side B, track 5]. Introduction The emergence of protest or a political popular music in the 1960s has been inextricably linked in the popular imaginary and public history with social change and youth revolt. -

Explorer's Guide Peruvian Music

EXPLORER’S GUIDE PERUVIAN MUSIC A shaman plays a flute alongside Amazonian Peru’s Boiling River. Facing the 1 2 3 4 Music in Hidden Workshop Andes Anthems Dinner and a Show Electric Inca Inside a storefront sign- Traditional Andean What originated as leftist, Follow up the show with Cusco posted simply “Luthier,” music isn’t something you anti-dictatorship music drinks and dancing at this expertly made Andean stumble across—it has to in the 1960s and ’70s has local staple for Andean While living among the instruments lie scattered be sought out. Wissler sug- morphed into Andean rock. Ukukus has live shows Q’eros, an indigenous around their maker. Sabino gests contacting Santos folk, supported by guitar, daily, while Sundays are Andean group in south- Huamán, a third-generation Machacca Apaza, a Q’ero, charango, various flutes, headlined by Amaru Puma east Peru, Holly Wissler stringed instrument crafts- to sit in on an offering to and drums. “People love it,” Kuntur, a band named for was immersed in their man, will demonstrate how apus (mountain gods) and says Wissler of the haunt- the three cosmic figures native music. Now based to play each charango, Pachamama (Mother Earth) ing melodies, which are of the Inca Empire (snake, in Cusco, the ethno- bandurria, guitar, and at his family’s home, 20 best enjoyed over dinner at puma, and condor). Here, musicologist and Nat quena flute. Ask to see his minutes outside Cusco. any number of restaurants folk music goes electric, Geo Expeditions expert workshop upstairs, says Request music up front so in Cusco, including the with hand pipes and quena outlines where to find Wissler—and even if you that his mother is around just opened Ayasqa, which flutes getting the rock- the best local beats.