The Walls of Megalopolis: an Analysis of the Circuit Course Proposed by the British Excavation of 1890-1893

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Athenians and Eleusinians in the West Pediment of the Parthenon

ATHENIANS AND ELEUSINIANS IN THE WEST PEDIMENT OF THE PARTHENON (PLATE 95) T HE IDENTIFICATION of the figuresin the west pedimentof the Parthenonhas long been problematic.I The evidencereadily enables us to reconstructthe composition of the pedimentand to identify its central figures.The subsidiaryfigures, however, are rath- er more difficult to interpret. I propose that those on the left side of the pediment may be identifiedas membersof the Athenian royal family, associatedwith the goddessAthena, and those on the right as membersof the Eleusinian royal family, associatedwith the god Posei- don. This alignment reflects the strife of the two gods on a heroic level, by referringto the legendary war between Athens and Eleusis. The recognition of the disjunctionbetween Athenians and Eleusinians and of parallelism and contrastbetween individualsand groups of figures on the pedimentpermits the identificationof each figure. The referenceto Eleusis in the pediment,moreover, indicates the importanceof that city and its majorcult, the Eleu- sinian Mysteries, to the Athenians. The referencereflects the developmentand exploitation of Athenian control of the Mysteries during the Archaic and Classical periods. This new proposalfor the identificationof the subsidiaryfigures of the west pedimentthus has critical I This article has its origins in a paper I wrote in a graduateseminar directedby ProfessorJohn Pollini at The Johns Hopkins University in 1979. I returned to this paper to revise and expand its ideas during 1986/1987, when I held the Jacob Hirsch Fellowship at the American School of Classical Studies at Athens. In the summer of 1988, I was given a grant by the Committeeon Research of Tulane University to conduct furtherresearch for the article. -

Genetics of the Peloponnesean Populations and the Theory of Extinction of the Medieval Peloponnesean Greeks

European Journal of Human Genetics (2017) 25, 637–645 Official journal of The European Society of Human Genetics www.nature.com/ejhg ARTICLE Genetics of the peloponnesean populations and the theory of extinction of the medieval peloponnesean Greeks George Stamatoyannopoulos*,1, Aritra Bose2, Athanasios Teodosiadis3, Fotis Tsetsos2, Anna Plantinga4, Nikoletta Psatha5, Nikos Zogas6, Evangelia Yannaki6, Pierre Zalloua7, Kenneth K Kidd8, Brian L Browning4,9, John Stamatoyannopoulos3,10, Peristera Paschou11 and Petros Drineas2 Peloponnese has been one of the cradles of the Classical European civilization and an important contributor to the ancient European history. It has also been the subject of a controversy about the ancestry of its population. In a theory hotly debated by scholars for over 170 years, the German historian Jacob Philipp Fallmerayer proposed that the medieval Peloponneseans were totally extinguished by Slavic and Avar invaders and replaced by Slavic settlers during the 6th century CE. Here we use 2.5 million single-nucleotide polymorphisms to investigate the genetic structure of Peloponnesean populations in a sample of 241 individuals originating from all districts of the peninsula and to examine predictions of the theory of replacement of the medieval Peloponneseans by Slavs. We find considerable heterogeneity of Peloponnesean populations exemplified by genetically distinct subpopulations and by gene flow gradients within Peloponnese. By principal component analysis (PCA) and ADMIXTURE analysis the Peloponneseans are clearly distinguishable from the populations of the Slavic homeland and are very similar to Sicilians and Italians. Using a novel method of quantitative analysis of ADMIXTURE output we find that the Slavic ancestry of Peloponnesean subpopulations ranges from 0.2 to 14.4%. -

The Satrap of Western Anatolia and the Greeks

University of Pennsylvania ScholarlyCommons Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations 2017 The aS trap Of Western Anatolia And The Greeks Eyal Meyer University of Pennsylvania, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations Part of the Ancient History, Greek and Roman through Late Antiquity Commons Recommended Citation Meyer, Eyal, "The aS trap Of Western Anatolia And The Greeks" (2017). Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations. 2473. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/2473 This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/2473 For more information, please contact [email protected]. The aS trap Of Western Anatolia And The Greeks Abstract This dissertation explores the extent to which Persian policies in the western satrapies originated from the provincial capitals in the Anatolian periphery rather than from the royal centers in the Persian heartland in the fifth ec ntury BC. I begin by establishing that the Persian administrative apparatus was a product of a grand reform initiated by Darius I, which was aimed at producing a more uniform and centralized administrative infrastructure. In the following chapter I show that the provincial administration was embedded with chancellors, scribes, secretaries and military personnel of royal status and that the satrapies were periodically inspected by the Persian King or his loyal agents, which allowed to central authorities to monitory the provinces. In chapter three I delineate the extent of satrapal authority, responsibility and resources, and conclude that the satraps were supplied with considerable resources which enabled to fulfill the duties of their office. After the power dynamic between the Great Persian King and his provincial governors and the nature of the office of satrap has been analyzed, I begin a diachronic scrutiny of Greco-Persian interactions in the fifth century BC. -

Early Mycenaean Arkadia: Space and Place(S) of an Inland and Mountainous Region

Early Mycenaean Arkadia: Space and Place(s) of an Inland and Mountainous Region Eleni Salavoura1 Abstract: The concept of space is an abstract and sometimes a conventional term, but places – where people dwell, (inter)act and gain experiences – contribute decisively to the formation of the main characteristics and the identity of its residents. Arkadia, in the heart of the Peloponnese, is a landlocked country with small valleys and basins surrounded by high mountains, which, according to the ancient literature, offered to its inhabitants a hard and laborious life. Its rough terrain made Arkadia always a less attractive area for archaeological investigation. However, due to its position in the centre of the Peloponnese, Arkadia is an inevitable passage for anyone moving along or across the peninsula. The long life of small and medium-sized agrarian communities undoubtedly owes more to their foundation at crossroads connecting the inland with the Peloponnesian coast, than to their potential for economic growth based on the resources of the land. However, sites such as Analipsis, on its east-southeastern borders, the cemetery at Palaiokastro and the ash altar on Mount Lykaion, both in the southwest part of Arkadia, indicate that the area had a Bronze Age past, and raise many new questions. In this paper, I discuss the role of Arkadia in early Mycenaean times based on settlement patterns and excavation data, and I investigate the relation of these inland communities with high-ranking central places. In other words, this is an attempt to set place(s) into space, supporting the idea that the central region of the Peloponnese was a separated, but not isolated part of it, comprising regions that are also diversified among themselves. -

Tourism Development in Greek Insular and Coastal Areas: Sociocultural Changes and Crucial Policy Issues

Tourism Development in Greek Insular and Coastal Areas: Sociocultural Changes and Crucial Policy Issues Paris Tsartas University of the Aegean, Michalon 8, 82100 Chios, Greece The paperanalyses two issuesthat have characterised tourism development inGreek insularand coastalareas in theperiod 1970–2000. The firstissue concerns the socioeco- nomic and culturalchanges that have taken place in theseareas and ledto rapid– and usuallyunplanned –tourismdevelopment. The secondissue consists of thepolicies for tourismand tourismdevelopment atlocal,regional and nationallevel. The analysis focuseson therole of thefamily, social mobility issues,the social role of specific groups, and consequencesfor the manners, customs and traditionsof thelocal popula- tion.It also examines the views and reactionsof localcommunities regarding tourism and tourists.There is consideration of thenew productive structuresin theseareas, including thedowngrading of agriculture,the dependence of many economicsectors on tourism,and thelarge increase in multi-activityand theblack economy. Another focusis on thecharacteristics of masstourism, and on therelated problems and criti- cismsof currenttourism policies. These issues contributed to amodel of tourism development thatintegrates the productive, environmental and culturalcharacteristics of eachregion. Finally, the procedures and problemsencountered in sustainabledevel- opment programmes aiming at protecting the environment are considered. Social and Cultural Changes Brought About by Tourism Development in the Period 1970–2000 The analysishere focuseson three mainareas where these changesare observed:sociocultural life, productionand communication. It should be noted thata large proportionof all empirical studies of changesbrought aboutby tourism development in Greece have been of coastal and insular areas. Social and cultural changes in the social structure The mostsignificant of these changesconcern the family andits role in the new ‘urbanised’social structure, social mobility and the choicesof important groups, such as young people and women. -

The Helot Revolt of Sparta Greece

464 B.C. The Helot Revolt of Sparta Greece Sparta, at first, was only the Messenia and Laconia territories, and later the Spartans (previously known as the Dorians) came and took over those territories. Those places they conquered had other residents who were captured and used them as Spartan “slaves” (also known as Helots) for the growing nation. However, these Helots were not the property of anyone or under the control of a specific person. They worked for Sparta in general, and since the Dorians couldn’t do agriculture, they made the Helots do the work. The Dorians were “Barbarians,” note them taking over territories. Unlike the slaves that we know today, these ones were able to go wherever they want in Spartan territory and they could live normal lives like the Spartans.The Helots lived in houses together for a plot of land that they worked on. They were allowed families, to go away from their house and make cash for themselves. Occasionally, the Helots would be assigned to help out in the military. However, not all Helots were happy where they were at. Around 660 B.C., the Spartans attacked the Argives, who demolished the Spartans. The report of Sparta’s lost gave encouragement to the Helots who started a revolt against Sparta, which is now known as the Second Messenian War. The Spartans were fighting to gain back control, but they were outnumbered seven Helots to one Spartan. The details about this war were concealed, and very little information is known about what happened in the war. -

Ancient History Sourcebook: 11Th Brittanica: Sparta SPARTA an Ancient City in Greece, the Capital of Laconia and the Most Powerful State of the Peloponnese

Ancient History Sourcebook: 11th Brittanica: Sparta SPARTA AN ancient city in Greece, the capital of Laconia and the most powerful state of the Peloponnese. The city lay at the northern end of the central Laconian plain, on the right bank of the river Eurotas, a little south of the point where it is joined by its largest tributary, the Oenus (mount Kelefina). The site is admirably fitted by nature to guard the only routes by which an army can penetrate Laconia from the land side, the Oenus and Eurotas valleys leading from Arcadia, its northern neighbour, and the Langada Pass over Mt Taygetus connecting Laconia and Messenia. At the same time its distance from the sea-Sparta is 27 m. from its seaport, Gythium, made it invulnerable to a maritime attack. I.-HISTORY Prehistoric Period.-Tradition relates that Sparta was founded by Lacedaemon, son of Zeus and Taygete, who called the city after the name of his wife, the daughter of Eurotas. But Amyclae and Therapne (Therapnae) seem to have been in early times of greater importance than Sparta, the former a Minyan foundation a few miles to the south of Sparta, the latter probably the Achaean capital of Laconia and the seat of Menelaus, Agamemnon's younger brother. Eighty years after the Trojan War, according to the traditional chronology, the Dorian migration took place. A band of Dorians united with a body of Aetolians to cross the Corinthian Gulf and invade the Peloponnese from the northwest. The Aetolians settled in Elis, the Dorians pushed up to the headwaters of the Alpheus, where they divided into two forces, one of which under Cresphontes invaded and later subdued Messenia, while the other, led by Aristodemus or, according to another version, by his twin sons Eurysthenes and Procles, made its way down the Eurotas were new settlements were formed and gained Sparta, which became the Dorian capital of Laconia. -

The Thermopylae Line

CHAPTER 6 THE THERMOPYLAE LINE ENERAL Wavell arrived in Athens on the 19th April and immediately e Gheld a conference at General Wilson's quarters . Although an effectiv decision to embark the British force from Greece had been made on a higher level in London, the commanders on the spot now once agai n deeply considered the pros and cons . The Greek Government was unstable and had suggested that the British force should depart in order to avoid further devastation of the country. It was unlikely that the Greek Army of Epirus could be extricated and some of its senior officers were urging sur- render. General Wilson considered that his force could hold the Ther- mopylae line indefinitely once the troops were in position.l "The arguments in favour of fighting it out, which [it] is always better to do if possible, " wrote Wilson later,2 "were : the tying up of enemy forces, army and air , which would result therefrom ; the strain the evacuation would place o n the Navy and Merchant Marine ; the effect on the morale of the troops and the loss of equipment which would be incurred . In favour of with- drawal the arguments were : the question as to whether our forces in Greece could be reinforced as this was essential ; the question of the maintenance of our forces, plus the feeding of the civil population ; the weakness of our air forces with few airfields and little prospect of receiving reinforcements ; the little hope of the Greek Army being able to recover its morale . The decision was made to withdraw from Greece ." The British leaders con- sidered that it was unlikely that they would be able to take out any equip- ment except that which the troops carried, and that they would be lucky "to get away with 30 per cent of the force" . -

Publication of an Amendment Application Pursuant to Article 6(2) of Council Regulation (EC) No 510/2006 on the Protection Of

C 186/18 EN Official Journal of the European Union 26.6.2012 Publication of an amendment application pursuant to Article 6(2) of Council Regulation (EC) No 510/2006 on the protection of geographical indications and designations of origin for agricultural products and foodstuffs (2012/C 186/10) This publication confers the right to object to the amendment application pursuant to Article 7 of Council Regulation (EC) No 510/2006 ( 1). Statements of objection must reach the Commission within six months of the date of this publication. AMENDMENT APPLICATION COUNCIL REGULATION (EC) No 510/2006 AMENDMENT APPLICATION IN ACCORDANCE WITH ARTICLE 9 ‘ΚΑΛΑΜΑΤΑ’ (KALAMATA) EC No: EL-PDO-0117-0037-21.12.2009 PGI ( ) PDO ( X ) 1. Heading in the specification affected by the amendment: — Name of product — ☒ Description of product — ☒ Geographical area — Proof of origin — ☒ Method of production — ☒ Link — Labelling — National requirements — Other (please specify) 2. Type of amendment(s): — Amendment to single document or summary sheet — ☒ Amendment to specification of registered PDO or PGI for which neither the single document nor the summary sheet has been published — Amendment to specification that requires no amendment to the published single document (Article 9(3) of Regulation (EC) No 510/2006) — Temporary amendment to specification resulting from imposition of obligatory sanitary or phytosanitary measures by public authorities (Article 9(4) of Regulation (EC) No 510/2006) 3. Amendment(s): 3.1. Description of product: In this application the olive oil produced is described in greater detail than in the initial registration dossier. Stricter quality specifications are laid down in order to ensure that the name is used only for the area's very best quality olive oil. -

Blood Ties: Religion, Violence, and the Politics of Nationhood in Ottoman Macedonia, 1878

BLOOD TIES BLOOD TIES Religion, Violence, and the Politics of Nationhood in Ottoman Macedonia, 1878–1908 I˙pek Yosmaog˘lu Cornell University Press Ithaca & London Copyright © 2014 by Cornell University All rights reserved. Except for brief quotations in a review, this book, or parts thereof, must not be reproduced in any form without permission in writing from the publisher. For information, address Cornell University Press, Sage House, 512 East State Street, Ithaca, New York 14850. First published 2014 by Cornell University Press First printing, Cornell Paperbacks, 2014 Printed in the United States of America Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Yosmaog˘lu, I˙pek, author. Blood ties : religion, violence,. and the politics of nationhood in Ottoman Macedonia, 1878–1908 / Ipek K. Yosmaog˘lu. pages cm Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-0-8014-5226-0 (cloth : alk. paper) ISBN 978-0-8014-7924-3 (pbk. : alk. paper) 1. Macedonia—History—1878–1912. 2. Nationalism—Macedonia—History. 3. Macedonian question. 4. Macedonia—Ethnic relations. 5. Ethnic conflict— Macedonia—History. 6. Political violence—Macedonia—History. I. Title. DR2215.Y67 2013 949.76′01—dc23 2013021661 Cornell University Press strives to use environmentally responsible suppliers and materials to the fullest extent possible in the publishing of its books. Such materials include vegetable-based, low-VOC inks and acid-free papers that are recycled, totally chlorine-free, or partly composed of nonwood fibers. For further information, visit our website at www.cornellpress.cornell.edu. Cloth printing 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 Paperback printing 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 To Josh Contents Acknowledgments ix Note on Transliteration xiii Introduction 1 1. -

Earthquake: Detailed Study of a Normal Fault, Evidences for East-West Extension in the Hellenic Arc H Lyon-Caen, R

The 1986 Kalamata (South Peloponnesus) Earthquake: Detailed Study of a Normal Fault, Evidences for East-West Extension in the Hellenic Arc H Lyon-Caen, R. Armijo, J Drakopoulos, J Baskoutass, N Delibassis, R. Gaulon, V Kouskouna, J Latoussakis, K. Makropoulos, P Papadimitriou, et al. To cite this version: H Lyon-Caen, R. Armijo, J Drakopoulos, J Baskoutass, N Delibassis, et al.. The 1986 Kalamata (South Peloponnesus) Earthquake: Detailed Study of a Normal Fault, Evidences for East-West Extension in the Hellenic Arc. Journal of Geophysical Research, American Geophysical Union, 1988, 93, pp.967 - 982. hal-01994159 HAL Id: hal-01994159 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-01994159 Submitted on 25 Jan 2019 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. JOURNAL OF GEOPHYSICAL RESEARCH, VOL. 93, NO. B12, PAGES 14,967-15,000, DECEMBER 10, 1988 The 1986Kalemate (South Peloponnesus) Earthquake' Detailed Study of a Normal Fault, Evidences for East-West Extension in the Hellenic Arc H. LYON-CAEN,1 R. ARMIJO,2 J. DRAKOPOULOS,3'4 J. BASKOUTASS,4 N. DELIBASSIS,3 R. GAULON,1 V. KOUSKOUNA,3 J. LATOUSSAKIS,4 K. MAKROPOULOS,3 P. -

NEW EOT-English:Layout 1

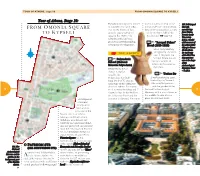

TOUR OF ATHENS, stage 10 FROM OMONIA SQUARE TO KYPSELI Tour of Athens, Stage 10: Papadiamantis Square), former- umental staircases lead to the 107. Bell-shaped FROM MONIA QUARE ly a garden city (with villas, Ionian style four-column propy- idol with O S two-storey blocks of flats, laea of the ground floor, a copy movable legs TO K YPSELI densely vegetated) devel- of the northern hall of the from Thebes, oped in the 1920’s - the Erechteion ( page 13). Boeotia (early 7th century suburban style has been B.C.), a model preserved notwithstanding 1.2 ¢ “Acropol Palace” of the mascot of subsequent development. Hotel (1925-1926) the Athens 2004 Olympic Games A five-story building (In the photo designed by the archi- THE SIGHTS: an exact copy tect I. Mayiasis, the of the idol. You may purchase 1.1 ¢Polytechnic Acropol Palace is a dis- tinctive example of one at the shops School (National Athens Art Nouveau ar- of the Metsovio Polytechnic) Archaeological chitecture. Designed by the ar- Resources Fund – T.A.P.). chitect L. Kaftan - 1.3 tzoglou, the ¢Tositsa Str Polytechnic was built A wide pedestrian zone, from 1861-1876. It is an flanked by the National archetype of the urban tra- Metsovio Polytechnic dition of Athens. It compris- and the garden of the 72 es of a central building and T- National Archaeological 73 shaped wings facing Patision Museum, with a row of trees in Str. It has two floors and the the middle, Tositsa Str is a development, entrance is elevated. Two mon- place to relax and stroll.