The Convention on Biological Diversity

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

![[The Insects of Tula District]. Priokskoe LA., 1988](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/3596/the-insects-of-tula-district-priokskoe-la-1988-123596.webp)

[The Insects of Tula District]. Priokskoe LA., 1988

OdonatologicalAbstracts of 1986 some no scientific significance; he compiled tales of earlier periods, which he selected for their morals their (10768) SHALAPYONAK, A.S., 1986. Strakozy (Odo- or singularity (cf. G. Morge, 1973,in : R.F. Smith et - al„ Ann. Re- nata, abo Odonatoptera). [Dragonflies (Odonata, [Eds], History ofentomology, p. 54, views, Palo is his 17-book syn. Odonatoptera)]. In: I P. Shamyakin et al., [Eds], Alto). Noteworthy trea- tise, “De animalium where Vol. 12, col. natura", 50 chapters are Encyklapedyya pryrody Byelarusi, 5, p. devoted pis 2-3 excl., Byelaruskaya Savyeckaya to insects. This includes the description of called “ ” Encyklapedyya, Minsk. (Beyeloruss.). an insect, hippouros (= “horse tail”), living around in the national the river Astraios in Macedonia. Based on its General, Byelorussian nat. hist, ency- description, behaviour and habitat, L.G. Fernandez clopaedia. In Byelorussia, there are ca 50 odon. spp., 21 of (1959, Manuales Anejos de which are shown on col. pis, along with their y Emerita, vol. 18, p. 47) its identification - The resp. Byelorussian “common” names. suggests as a “dragonfly”. ety- mology is here discussed in detail. If correct, this is the sole in classi- 1987 dragonfly appellationknown so far cal Greek. (10769) BULUHTO, N.P., 1987. Nasekomye Tul’skago - - (10771) DZENDZELEVSKIY, kraya. [The insects of Tula district]. Priokskoe LA., 1988. Strekoza. knizh. Izdat., Tula. [Dragonfly], In: R.l, Avanesov, The Slavic lin- 128 pp., 8 col. pis excl. ISBN [Ed ], atlas. Lexical and word-formational none. (Russ ). guistic series, I: The odon. dealt with 21-23, but The animal world, 19-24 (localities), 118-119 are briefly on pp. -

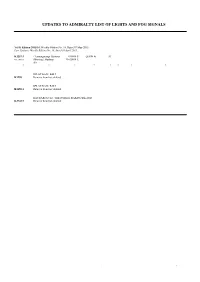

BA Amendments

UPDATES TO ADMIRALTY LIST OF LIGHTS AND FOG SIGNALS Vol K Edition 2015/16. Weekly Edition No. 19, Dated 07 May 2015. Last Updates: Weekly Edition No. 18, dated 30 April 2015. K1257·3 - Tanjungwangi Harbour 8 08·09 S Q(4)W 8s 10 ID, , 4041A (Meneng). Harbour 114 24·08 E (ID) ******** SELAT BALI. BALI K1258 Remove from list; deleted SELAT BALI. BALI K1258·1 Remove from list; deleted HAURAKI GULF. THE NOISES. RAKINO ISLAND K3742·2 Remove from list; deleted 5.9 Wk19/15 VI 5.+4,$ -/ /TAKHRGDC6J +@RS4OC@SDR6DDJKX$CHSHNM-N C@SDC OQHK 1 # 1!$ ".-2 / &$ !1 9(+ ADKNV/NMS@/HQ@ITA@+S (MRDQS ,@MNDK+T§R+S%KN@S!% mț̦2mț̦6 m 3 !Q@YHKH@M-NSHBD12#1 43., 3("(#$-3(%(" 3(.-2823$, (2 / &$ "'(- ADKNV'DMFWHM6QDBJ (MRDQS 'NMF8T@M mț̦-mț̦$ !QN@CB@RSRDUDQXLHMTSDR 5HQST@K ENQLDQTOC@SD "GHMDRD-NSHBD12#1 / &$ "'(- ADKNV'T@MFYD8@MF+S5DRRDK (MRDQS 'T@QTMCH@M&@MF+S!TNX-N mț̦-mț̦$ !QN@CB@RSRDUDQXLHMTSDR 1D@K 'T@QTMCH@M&@MF+S!TNX-N mț̦-mț̦$ !QN@CB@RSRDUDQXLHMTSDR 1D@K 'T@QTMCH@M&@MF+S!TNX-N mț̦-mț̦$ !QN@CB@RSRDUDQXLHMTSDR 1D@K 'T@QTMCH@M&@MF+S!TNX-N mț̦-mț̦$ !QN@CB@RSRDUDQXLHMTSDR 1D@K 'T@QTMCH@M&@MF+S!TNX-N mț̦-mț̦$ !QN@CB@RSRDUDQXLHMTSDR 1D@K 'T@QTMCH@M&@MF+S!TNX-N mț̦-mț̦$ !QN@CB@RSRDUDQXLHMTSDR 1D@K 'T@QTMCH@M&@MF+S!TNX-N mț̦-mț̦$ !QN@CB@RSRDUDQXLHMTSDR 1D@K 'T@QTMCH@M&@MF+S!TNX-N mț̦-mț̦$ !QN@CB@RSRDUDQXLHMTSDR 1D@K 'T@QTMCH@M&@MF+S!TNX-N mț̦-mț̦$ !QN@CB@RSRDUDQXLHMTSDR 1D@K 'T@QTMCH@M&@MF+S!TNX-N mț̦-mț̦$ !QN@CB@RSRDUDQXLHMTSDR 1D@K 'T@QTMCH@M&@MF+S!TNX-N mț̦-mț̦$ !QN@CB@RSRDUDQXLHMTSDR 1D@K 'T@QTMCH@M&@MF+S!TNX-N mț̦-mț̦$ !QN@CB@RSRDUDQXLHMTSDR -

Update of Part Of

FIJI Introduction Area: 18,272 sq.km. Population: 827,900 (2007). Fiji is an independent island republic in the South Pacific, situated between latitudes 15° South and 21° South and straddling the 180th meridian from 177° West to 175° East. The 320 or so islands form a complex group of high islands of volcanic origin, with barrier reefs, atolls, sand cays and raised coral islands. The two largest islands, Viti Levu (10,386 sq.km) and Vanua Levu (5,535 sq.km), together comprise 87% of the total land area. Two smaller islands, Taveuni (435 sq.km) and Kadavu (408 sq.km), account for a further 4.6% of the land area, and most of the remaining islands are very small. Less than a hundred of the islands are inhabited, most of the population being concentrated in the towns, villages and lowlands of the two larger land masses. The annual population growth is 2% and the population density is 39 inhabitants per sq.km. Suva, the capital city, is located on a peninsula near the southeastern corner of Viti Levu. Fiji has an equable maritime climate, a consequence of its high topography and prevailing winds, the Southeast Trades. The west coast of Viti Levu is in a rain shadow, and thus experiences a distinct dry season. Maximum and minimum temperatures for Suva are 30°C and 20.5°C respectively. The dry season extends from May to October, and the wet season from November to April. Mean relative humidities are 80% and 75% at 0800 hrs and 1400 hrs respectively on the east coast, and about 10% lower on the west coast. -

The Great Sea Reef Weaving Together Communities for Conservation

CASE STUDY FIJI 2017 THE GREAT SEA REEF WEAVING TOGETHER COMMUNITIES FOR CONSERVATION Weaving together communities for conservation page 1 WWF-PACIFIC VISION Our vision is for empowered and resilient Pacific island CONTENts communities living our unique culture to conserve and manage our ocean, forests and rivers for improved food security, human well-being and a sustainable future. CAKAULEVu – FIJI’S HIDDEN GEM 5 PROTECTING CAKAULEVu – eVERYONE’S BUSINESS 10 WWF MISSION WWF’s mission is to stop the degradation of the planet’s natural environment and to TOOLS AND AppROACHEs – 12 BEYOND SMALL TABU AREAS build a future in which humans live in harmony with nature by : • Conserving the world’s biological diversity; Marine Protected Areas – the tabu system 12 • Ensuring that the use of renewable natural resources is sustainable; The Fiji Locally Managed Marine Area Network (FLMMA) 12 • Promoting the reduction of pollution and wasteful consumption. ________________________________ Turtle Monitors – from hunter to guardian 14 Text compiled by Seema Deo. Sustainable Fisheries — setting smarter limits 15 Layout and Graphics by Kalo Williams. Raising the Fish Value — improving postharvest handling 16 SPECIAL THANKS TO WWF staff Kesaia Tabunakawai, Jackie Thomas, Qela Waqabitu, Tui Marseu, and Vilisite Tamani, for providing information for the report. Sustainable Seafood — a reef-to-resort approach 17 Exploring Alternatives to Fisheries — 18 Published in April 2017 by WWF-Pacific, World Wide Fund For Nature, Suva, Fiji. support through microfinancing Any reproduction in full or in part must mention the title and credit as the copyright owner. Women in Fisheries — building a business approach 18 © Text 2017 WWF Pacific. -

Essential Waters: Young Bull Sharks in Fiji's Largest Riverine System

Received: 4 December 2018 | Revised: 3 March 2019 | Accepted: 4 March 2019 DOI: 10.1002/ece3.5304 ORIGINAL RESEARCH Essential waters: Young bull sharks in Fiji’s largest riverine system Kerstin B. J. Glaus1 | Juerg M. Brunnschweiler2 | Susanna Piovano1 | Gauthier Mescam3 | Franziska Genter4 | Pascal Fluekiger4 | Ciro Rico1,5 1Faculty of Science, Technology and Environment, School of Marine Studies, The Abstract University of the South Pacific, Suva, Fiji Coastal and estuarine systems provide critical shark habitats due to their relatively 2 Independent Researcher, Zurich, high productivity and shallow, protected waters. The young (neonates, young‐of‐the‐ Switzerland 3Projects Abroad, Shark Conservation year, and juveniles) of many coastal shark species occupy a diverse range of habi‐ Project Fiji, Goring‐by‐Sea, UK tats and areas where they experience environmental variability, including acute and 4 Department of Environmental Systems seasonal shifts in local salinities and temperatures. Although the location and func‐ Science, ETH Zurich, Zurich, Switzerland tioning of essential shark habitats has been a focus in recent shark research, there 5Instituto de Ciencias Marinas de Andalucía (ICMAN), Consejo Superior de is a paucity of data from the South Pacific. In this study, we document the tem‐ Investigaciones Científicas, Puerto Real, poral and spatial distribution, age class composition, and environmental parameters Cádiz, Spain of young bull sharks (Carcharhinus leucas) in the Rewa, Sigatoka, and Navua Rivers, Correspondence Fiji's three largest riverine systems. One hundred and seventy‐two young bull sharks Kerstin B. J. Glaus, Faculty of Science, Technology and Environment, School of were captured in fisheries-independent surveys from January 2016 to April 2018. -

By the Lepidoptera (Eg Patterns Are Frequently Used

Odonatologica 15(3): 335-345 September I, 1986 A survey of some Odonata for ultravioletpatterns* D.F.J. Hilton Department of Biological Sciences, Bishop’s University, Lennoxville, Quebec, J1M 1Z7, Canada Received May 8, 1985 / Revised and Accepted March 3, 1986 series of 338 in families A museum specimens comprising spp. 118 genera and 16 were photographed both with and without a Kodak 18-A ultraviolet (UV) filter. These photographs revealed that only Euphaeaamphicyana reflected UV from its other wings whereas all spp. either did not absorb UV (e.g. 94.5% of the Coenagri- did In with flavescent. onidae) or so to varying degrees. particular, spp. orange or brown UV these wings (or wing patches) exhibited absorption for same areas. However, other spp. with nearly transparent wings (especially certain Gomphidae) Pruinose also had strong UV absorption. body regions reflected UV but the standard acetone treatment for color preservation dissolves thewax particles of the pruinosity and destroys UV reflectivity. As is typical for arthropod cuticle, non-pruinosebody regions absorbed UV and this obscured whatever color patterns might otherwise be visible without the camera’s UV filter. Frequently there is sexual dimorphismin UV and and these role various of patterns (wings body) differences may play a in aspects mating behavior. INTRODUCTION Considerable attention has been paid to the various ultraviolet (UV) patterns exhibited by the Lepidoptera (e.g. SCOTT, 1973). Studies have shown (e.g. RUTOWSKI, 1981) that differing UV-reflectance patterns are frequently used as visual in various of behavior. few insect cues aspects mating Although a other groups have been investigated for the presence of UV patterns (HINTON, 1973; POPE & HINTON, 1977; S1LBERGL1ED, 1979), little informationis available for the Odonata. -

Leaving Place, Restoring Home Enhancing the Evidence Base on Planned Relocation Cases in the Context of Hazards, Disasters, and Climate Change

LEAVING PLACE, RESTORING HOME ENHANCING THE EVIDENCE BASE ON PLANNED RELOCATION CASES IN THE CONTEXT OF HAZARDS, DISASTERS, AND CLIMATE CHANGE By Erica Bower & Sanjula Weerasinghe March 2021 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS The authors wish to acknowledge the valuable support and feedback of several individuals and organizations in the preparation of this report. This includes members of the reference group: colleagues at the Platform on Disaster Displacement (Professor Walter Kälin, Sarah Koeltzow, Juan Carlos Mendez and Atle Solberg); members of the Platform on Disaster Displacement Advisory Committee including Bruce Burson (Independent Consultant), Beth Ferris (Georgetown University), Jane McAdam (UNSW Sydney) and Matthew Scott (Raoul Wallenberg Institute); colleagues at the International Organization for Migration (Alice Baillat, Pablo Escribano, Lorenzo Guadagno and Ileana Sinziana Puscas); colleagues at the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (Florence Geoffrey, Isabelle Michal and Michelle Yonetani); and colleagues at GIZ (Thomas Lennartz and Felix Ries). The authors also wish to acknowledge the assistance of Julia Goolsby, Sophie Offner and Chloe Schalit. This report has been carried out under the Platform on Disaster Displacement Work Plan 2019-2022 with generous funding support from the Federal Department of Foreign Affairs of Switzerland. It was co-commissioned by the Platform on Disaster Displacement and the Andrew & Renata Kaldor Centre for International Refugee Law at UNSW Sydney. Any feedback or questions about this report may -

Page 1 of 10 Phylogeny and Divergence Estimates for the Gasteruptiid Wasps (Hymenoptera : Evanioidea) Reveals a Correlation

Invertebrate Systematics 2020, 34, 319–327 © CSIRO 2020 doi:10.1071/IS19020_AC Supplementary material Phylogeny and divergence estimates for the gasteruptiid wasps (Hymenoptera : Evanioidea) reveals a correlation with hosts Ben A. ParslowA,B,E, John T. JenningsC, Michael P. SchwarzA and Mark I. StevensB,D ABiological Sciences, College of Science and Engineering, Flinders University, Adelaide, SA 5001, Australia. BSouth Australian Museum, North Terrace, GPO Box 234, Adelaide, SA 5000, Australia. CCentre for Evolutionary Biology and Biodiversity, and School of Biological Sciences, The University of Adelaide, SA 5005, Australia. DSchool of Pharmacy and Medical Sciences, University of South Australia, Adelaide, SA 5001, Australia. ECorresponding author. Email: [email protected] Fig. S1. Reconstruction ancestral state in phylogenies (RASP) analysis result, showing ancestral-state reconstruction of biogeography for all nodes. Main nodes discussed in the text are labelled with a letter. (See following page.) Page 1 of 10 Table S1. Specimen information Voucher numbers, species identification, GenBank accession numbers for C01, EF1-α and 28s gene fragments, collection localities and voucher location for all material used in this study are given. Abbreviations for collection locations are: PNG, Papua New Guinea; N.P., national park; C.P., conservation park; SA, South Australia; WA, Western Australia; Qld, Queensland; Tas., Tasmania; Vic., Victoria. Abbreviations for voucher location are: AMS, Australian Museum, Sydney, NSW, Australia; BPC, -

Cytochrome-B Evidence for Validity and Phylogenetic Relationships of Pseudobulweria and Bulweria (Procellariidae)

The Auk 115(1):188-195, 1998 CYTOCHROME-B EVIDENCE FOR VALIDITY AND PHYLOGENETIC RELATIONSHIPS OF PSEUDOBULWERIA AND BULWERIA (PROCELLARIIDAE) VINCENT BRETAGNOLLE,•'5 CAROLE A3VFII•,2 AND ERIC PASQUET3'4 •CEBC-CNRS, 79360 Beauvoirsur Niort, France; 2Villiers en Bois, 79360 Beauvoirsur Niort, France; 3Laboratoirede ZoologieMammi•res et Oiseaux,Museum National d'Histoire Naturelie, 55 rue Buffon,75005 Paris, France; and 4Laboratoirede Syst•matiquemol•culaire, CNRS-GDR 1005, Museum National d'Histoire Naturelie, 43 rue Cuvier, 75005 Paris, France ABSTRACT.--Althoughthe genus Pseudobulweria was described in 1936for the Fiji Petrel (Ps.macgillivrayi), itsvalidity, phylogenetic relationships, and the number of constituenttaxa it containsremain controversial. We tried to clarifythese issues with 496bp sequencesfrom the mitochondrialcytochrome-b gene of 12 taxa representingthree putative subspecies of Pseudobulweria,seven species in six othergenera of the Procellariidae(fulmars, petrels, and shearwaters),and onespecies each from the Hydrobatidae(storm-petrels) and Pelecanoidi- dae (diving-petrels).We alsoinclude published sequences for two otherpetrels (Procellaria cinereaand Macronectesgiganteus ) and use Diomedeaexulans and Pelecanuserythrorhynchos as outgroups.Based on thepronounced sequence divergence (5 to 5.5%)and separate phylo- genetichistory from othergenera that havebeen thought to be closelyrelated to or have beensynonymized with Pseudobulweria,we conclude that the genusis valid, and that the MascarenePetrel (Pseudobulweria aterrima) -

Great Sea Reef

A Living Icon Insured Sustain-web of life creating it-livelihoods woven in it Fiji’s Great Sea Reef Foreword Fiji’s Great Sea Reef (GSR), locally known as ‘Cakaulevu’ or ‘Bai Kei Viti’, remain one of the most productive and biologically diverse reef systems in the Southern Hemisphere. But despite its uniqueness and diversity it remains the most used with its social, cultural, economic and environmental value largely ignored. A Living Icon Insured Stretching for over 200km from the north eastern tip of Udu point in Vanua Levu to Bua at the north- Sustain-web of life creating it-livelihoods woven in it west edge of Vanua Levu, across the Vatu-i-ra passage, veering off along the way, to hug the coastline of Ra and Ba provinces and fusing into the Yasawa Islands, the Great Sea Reef snakes its way across the Fiji’s Great Sea Reef western sections of Fiji’s ocean. Also referred to as Fiji’s Seafood Basket, the reef feeds up to 80 percent of Fiji’s population.There are estimates that the reef system contributes between FJD 12-16 million annually to Fiji’s economy through the inshore fisheries sector, a conservative value. The stories in this book encapsulates the rich tapestry of interdependence between individuals and communities with the GSR, against the rising tide of challenges brought on by climate change through ocean warming and acidification, coral bleaching, sea level rise, and man-made challenges of pollution, overfishing and loss of habitat in the face of economic development. But all is not lost as communities and individuals are strengthened through sheer determination to apply their traditional knowledge, further strengthened by science and research to safeguard and protect the natural resource that is home and livelihood. -

Heritage Trees of Fiji

Heritage Trees of Fiji Workshop Report 25th March 2003, Lami, Fiji A Collaborative Project Supported by: Ministry of Fijian Affairs Department of the Environment Ministry of Fisheries and Forests Wildlife Conservation Society Report Prepared by: Wildlife Conservation Society – South Pacific 11 Ma’afu Street, Suva, Fiji Tel: (679) 331-5174, E-mail: [email protected] 1 Table of Contents Executive Summary …………………………………………………………… 3 Acknowledgements ……………………………………………………………. 5 List of Participants …………………………………………………………….. 6 Heritage Trees: An Introduction ……………………………………………. 7 The Heritage Tree Concept for Fiji …………………………………………. 9 Heritage Tree Mapping ……………………………………………………….. 11 Can a Heritage Tree Program Benefit Fiji? ………………………………. 13 Comments and Next Steps…………………………………………………... 14 Conclusions ……………………………………………………………………. 14 Appendix 1. Preliminary Heritage Tree Sites and Areas of Fiji Appendix 2. Examples of Heritage Tree Programs around the World Photo Credits: (In order of appearance) cover, Sovi Basin, D. Jackson; Yadua Taba Island, D. Olson; Medrausucu Range, V. Masibalavu; Waivudawa, D. Olson; Medrausucu Range, V. Masibalavu; masked shining parrot & collared lory, R. Morris; Fiji stamp, Post Fiji and G. Bennett 2 Executive Summary Heritage trees are trees of great size, old age, or have cultural or historical significance that have been formally recognized and protected by countries and cultures. We explored the value of a heritage tree program for Fiji, asking whether the concept was appropriate and useful for conserving Fiji’s biological wealth or if a program could be helpful in implementing the National Biodiversity Strategy and Action Plan. Large trees were recognized for their important biological values, including providing food and habitat for wildlife, such as shining parrots, and in the regeneration and maintenance of natural forests. Fijians can also benefit economically from the protection of very large trees through ecotourism activities and the conservation of important genetic resources from these ancient survivors. -

AOS Classification Committee – North and Middle America Proposal Set 2018-B 17 January 2018

AOS Classification Committee – North and Middle America Proposal Set 2018-B 17 January 2018 No. Page Title 01 02 Split Fork-tailed Swift Apus pacificus into four species 02 05 Restore Canada Jay as the English name of Perisoreus canadensis 03 13 Recognize two genera in Stercorariidae 04 15 Split Red-eyed Vireo (Vireo olivaceus) into two species 05 19 Split Pseudobulweria from Pterodroma 06 25 Add Tadorna tadorna (Common Shelduck) to the Checklist 07 27 Add three species to the U.S. list 08 29 Change the English names of the two species of Gallinula that occur in our area 09 32 Change the English name of Leistes militaris to Red-breasted Meadowlark 10 35 Revise generic assignments of woodpeckers of the genus Picoides 11 39 Split the storm-petrels (Hydrobatidae) into two families 1 2018-B-1 N&MA Classification Committee p. 280 Split Fork-tailed Swift Apus pacificus into four species Effect on NACC: This proposal would change the species circumscription of Fork-tailed Swift Apus pacificus by splitting it into four species. The form that occurs in the NACC area is nominate pacificus, so the current species account would remain unchanged except for the distributional statement and notes. Background: The Fork-tailed Swift Apus pacificus was until recently (e.g., Chantler 1999, 2000) considered to consist of four subspecies: pacificus, kanoi, cooki, and leuconyx. Nominate pacificus is highly migratory, breeding from Siberia south to northern China and Japan, and wintering in Australia, Indonesia, and Malaysia. The other subspecies are either residents or short distance migrants: kanoi, which breeds from Taiwan west to SE Tibet and appears to winter as far south as southeast Asia.