Insights and Regrets of a Foreign Geoscientist in the Pacific Islands

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

This Article Appeared in a Journal Published by Elsevier. the Attached Copy Is Furnished to the Author for Internal Non-Commerci

This article appeared in a journal published by Elsevier. The attached copy is furnished to the author for internal non-commercial research and education use, including for instruction at the authors institution and sharing with colleagues. Other uses, including reproduction and distribution, or selling or licensing copies, or posting to personal, institutional or third party websites are prohibited. In most cases authors are permitted to post their version of the article (e.g. in Word or Tex form) to their personal website or institutional repository. Authors requiring further information regarding Elsevier’s archiving and manuscript policies are encouraged to visit: http://www.elsevier.com/copyright Author's personal copy Journal of Anthropological Archaeology 29 (2010) 113–124 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Journal of Anthropological Archaeology journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/jaa Paleoclimates and the emergence of fortifications in the tropical Pacific islands Julie S. Field a, Peter V. Lape b,* a Department of Anthropology, The Ohio State University, United States b Department of Anthropology, University of Washington, Seattle, United States article info a b s t r a c t Article history: Paleoclimatic data from the tropical Pacific islands are compared to archaeological evidence for fortifica- Received 14 July 2009 tion construction in the Holocene. The results suggest that in some regions, people constructed more for- Revision received 5 November 2009 tifications during periods that match the chronology for the Little Ice Age (AD 1450–1850) in the Available online 31 December 2009 Northern Hemisphere. Periods of storminess and drought associated with the El Niño Southern Oscilla- tion have less temporal correlation with the emergence of fortifications in the Pacific, but significant spa- Keywords: tial correlation with the most severe conditions associated with this cycle. -

Central Division

THE FOLLOWING IS THE PROVISIONAL LIST OF POLLING VENUES AS AT 3IST DECEMBER 2017 CENTRAL DIVISION The following is a Provisional List of Polling Venues released by the Fijian Elections Office FEO[ ] for your information. Members of the public are advised to log on to pvl.feo.org.fj to search for their polling venues by district, area and division. DIVISION: CENTRAL AREA: VUNIDAWA PRE POLL VENUES -AREA VUNIDAWA Voter No Venue Name Venue Address Count Botenaulu Village, Muaira, 1 Botenaulu Community Hall 78 Naitasiri Delailasakau Community Delailasakau Village, Nawaidi- 2 107 Hall na, Naitasiri Korovou Community Hall Korovou Village, Noimalu , 3 147 Naitasiri Naitasiri Laselevu Village, Nagonenicolo 4 Laselevu Community Hall 174 , Naitasiri Lomai Community Hall Lomai Village, Nawaidina, 5 172 Waidina Naitasiri 6 Lutu Village Hall Wainimala Lutu Village, Muaira, Naitasiri 123 Matainasau Village Commu- Matainasau Village, Muaira , 7 133 nity Hall Naitasiri Matawailevu Community Matawailevu Village, Noimalu , 8 74 Hall Naitasiri Naitasiri Nabukaluka Village, Nawaidina ELECTION DAY VENUES -AREA VUNIDAWA 9 Nabukaluka Community Hall 371 , Naitasiri Nadakuni Village, Nawaidina , Voter 10 Nadakuni Community Hall 209 No Venue Name Venue Address Naitasiri Count Nadovu Village, Muaira , Nai- Bureni Settlement, Waibau , 11 Nadovu Community Hall 160 1 Bureni Community Hall 83 tasiri Naitasiri Naitauvoli Village, Nadara- Delaitoga Village, Matailobau , 12 Naitauvoli Community Hall 95 2 Delaitoga Community Hall 70 vakawalu , Naitasiri Naitasiri Nakida -

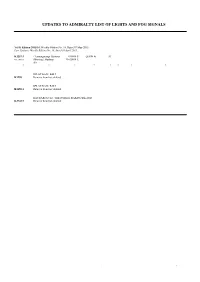

BA Amendments

UPDATES TO ADMIRALTY LIST OF LIGHTS AND FOG SIGNALS Vol K Edition 2015/16. Weekly Edition No. 19, Dated 07 May 2015. Last Updates: Weekly Edition No. 18, dated 30 April 2015. K1257·3 - Tanjungwangi Harbour 8 08·09 S Q(4)W 8s 10 ID, , 4041A (Meneng). Harbour 114 24·08 E (ID) ******** SELAT BALI. BALI K1258 Remove from list; deleted SELAT BALI. BALI K1258·1 Remove from list; deleted HAURAKI GULF. THE NOISES. RAKINO ISLAND K3742·2 Remove from list; deleted 5.9 Wk19/15 VI 5.+4,$ -/ /TAKHRGDC6J +@RS4OC@SDR6DDJKX$CHSHNM-N C@SDC OQHK 1 # 1!$ ".-2 / &$ !1 9(+ ADKNV/NMS@/HQ@ITA@+S (MRDQS ,@MNDK+T§R+S%KN@S!% mț̦2mț̦6 m 3 !Q@YHKH@M-NSHBD12#1 43., 3("(#$-3(%(" 3(.-2823$, (2 / &$ "'(- ADKNV'DMFWHM6QDBJ (MRDQS 'NMF8T@M mț̦-mț̦$ !QN@CB@RSRDUDQXLHMTSDR 5HQST@K ENQLDQTOC@SD "GHMDRD-NSHBD12#1 / &$ "'(- ADKNV'T@MFYD8@MF+S5DRRDK (MRDQS 'T@QTMCH@M&@MF+S!TNX-N mț̦-mț̦$ !QN@CB@RSRDUDQXLHMTSDR 1D@K 'T@QTMCH@M&@MF+S!TNX-N mț̦-mț̦$ !QN@CB@RSRDUDQXLHMTSDR 1D@K 'T@QTMCH@M&@MF+S!TNX-N mț̦-mț̦$ !QN@CB@RSRDUDQXLHMTSDR 1D@K 'T@QTMCH@M&@MF+S!TNX-N mț̦-mț̦$ !QN@CB@RSRDUDQXLHMTSDR 1D@K 'T@QTMCH@M&@MF+S!TNX-N mț̦-mț̦$ !QN@CB@RSRDUDQXLHMTSDR 1D@K 'T@QTMCH@M&@MF+S!TNX-N mț̦-mț̦$ !QN@CB@RSRDUDQXLHMTSDR 1D@K 'T@QTMCH@M&@MF+S!TNX-N mț̦-mț̦$ !QN@CB@RSRDUDQXLHMTSDR 1D@K 'T@QTMCH@M&@MF+S!TNX-N mț̦-mț̦$ !QN@CB@RSRDUDQXLHMTSDR 1D@K 'T@QTMCH@M&@MF+S!TNX-N mț̦-mț̦$ !QN@CB@RSRDUDQXLHMTSDR 1D@K 'T@QTMCH@M&@MF+S!TNX-N mț̦-mț̦$ !QN@CB@RSRDUDQXLHMTSDR 1D@K 'T@QTMCH@M&@MF+S!TNX-N mț̦-mț̦$ !QN@CB@RSRDUDQXLHMTSDR 1D@K 'T@QTMCH@M&@MF+S!TNX-N mț̦-mț̦$ !QN@CB@RSRDUDQXLHMTSDR -

Survival Guide on the Road

©Lonely Planet Publications Pty Ltd PAGE ON THE YOUR COMPLETE DESTINATION GUIDE 42 In-depth reviews, detailed listings ROAD and insider tips Vanua Levu & Taveuni p150 The Mamanuca & Yasawa Groups p112 Ovalau & the Lomaiviti Group Nadi, Suva & Viti Levu p137 p44 Kadavu, Lau & Moala Groups p181 PAGE SURVIVAL VITAL PRACTICAL INFORMATION TO 223 GUIDE HELP YOU HAVE A SMOOTH TRIP Directory A–Z .................. 224 Transport ......................... 232 Directory Language ......................... 240 student-travel agencies A–Z discounts on internatio airfares to full-time stu who have an Internatio Post offices 8am to 4pm Student Identity Card ( Accommodation Monday to Friday and 8am Application forms are a Index ................................ 256 to 11.30am Saturday Five-star hotels, B&Bs, able at these travel age Restaurants lunch 11am to hostels, motels, resorts, tree- Student discounts are 2pm, dinner 6pm to 9pm houses, bungalows on the sionally given for entr or 10pm beach, campgrounds and vil- restaurants and acco lage homestays – there’s no Shops 9am to 5pm Monday dation in Fiji. You ca Map Legend ..................... 263 to Friday and 9am to 1pm the student health shortage of accommodation ptions in Fiji. See the ‘Which Saturday the University of nd?’ chapter, p 25 , for PaciÀ c (USP) in ng tips and a run-down hese options. Customs Regulations E l e c t r Visitors can leave Fiji without THIS EDITION WRITTEN AND RESEARCHED BY Dean Starnes, Celeste Brash, Virginia Jealous “All you’ve got to do is decide to go and the hardest part is over. So go!” TONY WHEELER, COFOUNDER – LONELY PLANET Get the right guides for your trip PAGE PLAN YOUR PLANNING TOOL KIT 2 Photos, itineraries, lists and suggestions YOUR TRIP to help you put together your perfect trip Welcome to Fiji ............... -

We Are Kai Tonga”

5. “We are Kai Tonga” The islands of Moala, Totoya and Matuku, collectively known as the Yasayasa Moala, lie between 100 and 130 kilometres south-east of Viti Levu and approximately the same distance south-west of Lakeba. While, during the nineteenth century, the three islands owed some allegiance to Bau, there existed also several family connections with Lakeba. The most prominent of the few practising Christians there was Donumailulu, or Donu who, after lotuing while living on Lakeba, brought the faith to Moala when he returned there in 1852.1 Because of his conversion, Donu was soon forced to leave the island’s principal village, Navucunimasi, now known as Naroi. He took refuge in the village of Vunuku where, with the aid of a Tongan teacher, he introduced Christianity.2 Donu’s home island and its two nearest neighbours were to be the scene of Ma`afu’s first military adventures, ostensibly undertaken in the cause of the lotu. Richard Lyth, still working on Lakeba, paid a pastoral visit to the Yasayasa Moala in October 1852. Despite the precarious state of Christianity on Moala itself, Lyth departed in optimistic mood, largely because of his confidence in Donu, “a very steady consistent man”.3 He observed that two young Moalan chiefs “who really ruled the land, remained determined haters of the truth”.4 On Matuku, which he also visited, all villages had accepted the lotu except the principal one, Dawaleka, to which Tui Nayau was vasu.5 The missionary’s qualified optimism was shattered in November when news reached Lakeba of an attack on Vunuku by the two chiefs opposed to the lotu. -

Reef Check Description of the 2000 Mass Coral Beaching Event in Fiji with Reference to the South Pacific

REEF CHECK DESCRIPTION OF THE 2000 MASS CORAL BEACHING EVENT IN FIJI WITH REFERENCE TO THE SOUTH PACIFIC Edward R. Lovell Biological Consultants, Fiji March, 2000 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS 1.0 Introduction ...................................................................................................................................4 2.0 Methods.........................................................................................................................................4 3.0 The Bleaching Event .....................................................................................................................5 3.1 Background ................................................................................................................................5 3.2 South Pacific Context................................................................................................................6 3.2.1 Degree Heating Weeks.......................................................................................................6 3.3 Assessment ..............................................................................................................................11 3.4 Aerial flight .............................................................................................................................11 4.0 Survey Sites.................................................................................................................................13 4.1 Northern Vanua Levu Survey..................................................................................................13 -

Leaving Place, Restoring Home Enhancing the Evidence Base on Planned Relocation Cases in the Context of Hazards, Disasters, and Climate Change

LEAVING PLACE, RESTORING HOME ENHANCING THE EVIDENCE BASE ON PLANNED RELOCATION CASES IN THE CONTEXT OF HAZARDS, DISASTERS, AND CLIMATE CHANGE By Erica Bower & Sanjula Weerasinghe March 2021 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS The authors wish to acknowledge the valuable support and feedback of several individuals and organizations in the preparation of this report. This includes members of the reference group: colleagues at the Platform on Disaster Displacement (Professor Walter Kälin, Sarah Koeltzow, Juan Carlos Mendez and Atle Solberg); members of the Platform on Disaster Displacement Advisory Committee including Bruce Burson (Independent Consultant), Beth Ferris (Georgetown University), Jane McAdam (UNSW Sydney) and Matthew Scott (Raoul Wallenberg Institute); colleagues at the International Organization for Migration (Alice Baillat, Pablo Escribano, Lorenzo Guadagno and Ileana Sinziana Puscas); colleagues at the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (Florence Geoffrey, Isabelle Michal and Michelle Yonetani); and colleagues at GIZ (Thomas Lennartz and Felix Ries). The authors also wish to acknowledge the assistance of Julia Goolsby, Sophie Offner and Chloe Schalit. This report has been carried out under the Platform on Disaster Displacement Work Plan 2019-2022 with generous funding support from the Federal Department of Foreign Affairs of Switzerland. It was co-commissioned by the Platform on Disaster Displacement and the Andrew & Renata Kaldor Centre for International Refugee Law at UNSW Sydney. Any feedback or questions about this report may -

Fijian Frontiers Richard Smith © 2015

destination report | kadavu | fiji FIJIAN FRONTIERS RICHARD SMITH © 2015 FIJI IS CONSIDERED BY MANY AS THE SOFT CORAL CAPITAL OF THE WORLD, BUT THIS DIVERSE NATION HAS MUCH MORE TO OFFER THAN SOFT CORALS ALONE. I GUIDED A GROUP OF DIVERS TO KADAVU ISLAnd’S REMOTE SOUTH EASTERN COAST TO SHARe Fiji’S INDIGENOUS MARINE LIFE, STUNNING REEFS DOMINATED BY DIVERSE HARD CORALS, AND TO EXPERIENCE SOME RICH LOCAL CULTURE. rom the capital Nadi, we headed to found in Fiji’s waters almost immediately Kadavu southwest of the main island of on descent, I had high hopes for finding FViti Levu. The 45 minute flight in a 12 some of the others before we left. After a seater plane offered amazing views of the second great dive at Manta Reef and a aquamarine reefs below and the rainforest fleeting visit by a pure black ‘Darth Vader’ wilderness on Kadavu. This is one of the manta we headed back to the resort to try few great stands of forest remaining in the out the house reef. island group and it harbours a wealth of globally important terrestrial animal and Closer to home The resort ‘taxi service’ plant populations, as well as fantastic reefs. dropped us along the reef and we swam back to the resort during the dive. The After landing, a quick hop in a truck, guides explained the highlights and told a couple of boats made the hour long us to swim slowly to appreciate the smaller journey to the resort through endless inhabitants. There were many nudibranchs forests which tumbled into the coral fringed to keep us enthralled for the whole dive. -

Pr52 Pdf 17126.Pdf

The Australian Centre for International Agriculture Research (ACIAR) was established in June 1982 by an Act of the Australian Parliament. Its mandate is to help identify agricultural problems in developing countries and to commission collaborative research between Australian and developing country researchers in tields where Australia has special research competence. Where trade names ilre used this does not constitute endorsement of nor discrimination against any product by the Centre. ACIAR PROCEEDINGS This series of publications includes the full proceedings of research workshops or symposea organised or supported by ACTAR. Numbers in this series are distributed internationally to selected individuals and scientific institutions. Recent numbers in the series are listed inside the back cover. @ Australian Centre for International Agricultural Research, G.P.O. Box 1571, Canberra, A.C.T. 2601 Blaber, SJ.M .. Milton, D.A. and Rawlinson. NJ.F. (ed.) Tuna Baitfish in Fiji and Solomon Islands: proceedings of a workshop, Suva, Fiji, 17-18 August 1993. ACIAR Proceedings No. 52. 136 p. ISBN 1 86320 I 10 6 Production management: P.W. Lynch Design and production: BPD Graphic Associates, Canberra, Australia Printed by: Australian Print Group, Maryborough, Australia Tuna Baitfish in Fij i and Solomon Islands Proceedings of a workshop, Nadi, Fiji 17-18 August 1993 Editors: S.J.M. Blaber, D.A. Milton and N.J.F. Rawlinson Contents Introduction iv Acknowledgments vi BACKGROUND Fiji baitfishery status report S.P. Sharma 3 An industry perspective Navitalai Volavola 6 A review of previous baitfish studies and reports in Fiji N.l.F. Rawlinson 8 Analysis of historical tuna baitfish catch and effort data from Fiji with an assessment of the current status of the stocks N.l.F. -

Emergency Response Update Tropical Cyclone Gita in Samoa, Tonga & Fiji 27 February 2018

Emergency Response Update Tropical Cyclone Gita in Samoa, Tonga & Fiji 27 February 2018 HIGHLIGHTS • Between 9 and 14 February, Tropical Cyclone (TC) Gita brought damaging winds, storm surges and rain to Samoa, Tonga and Fiji. • As the Cluster Lead Agency for Health in the Pacific, WHO has supported the development of the Tonga Health, Nutrition and WASH Cluster Response Plan, deployed four staff to Tonga, and dispatched emergency supplies. WHO is also supporting the mental health and psychosocial response in Tonga through the training of nurses and counsellors. • At the request of the Ministry of Health of Samoa, WHO dispatched emergency Health and WASH supplies. SITUATION • Between 9 and 14 February, TC Gita brought damaging winds, storm surges and rain to Fiji, Samoa and Tonga. • In Samoa, TC Gita brought heavy rain and flooding. No casualties were reported. However, houses and infrastructure were damaged and power and water supply was interrupted. • In Tonga, TC Gita impacted the islands of Tongatapu and ‘Eua as a Category 4 storm. Destructive winds up to 278kph were recorded, as well as storm surges and heavy rain, affecting approximately 80,000 people. One fatality was recorded, several people were injured, and approximately 4,500 people took shelter in evacuation centers. There was significant damage to housing and infrastructure, and interruption of power and water supplies. • Tonga was already responding to a dengue outbreak prior to TC Gita striking, making post-disaster infectious disease surveillance and response an urgent priority. • In Fiji, TC Gita impacted the Southern Lau island group and Kadavu Island as a Category 4. -

Sche MID-Pacavrgravone

TULV. 15:22. XXIV. No. 1. Cents a Copy. 41111111111111inta 11/ unummatommork mlluMatimmmummaleiniliiim sche MID-PACargv rAVONE and the BULLETIN OF THE PAN-PACIFIC UNION Cr; Wallace R. Farrington, Governor of Hawaii and President of the Pan-Pacific Union. accepting the flag of Japan sent to the Union by the late Premier Hara by Hon. C. Yada, the first Pan-Pacific Minister of Friendship. li err SIIHMIIIIIIIIMIIIIIIIIIIIII103031111111111111110011111111111111111:1111111111110161111111111111MMUM11111111111MIIMMIH11111134 JAVA NITED STATES AUSTRALASIA HAWAII ORIENT Ara. News Co. Gordon & Goteb Pan-Pacific Union Kelly & Walsh Javasche Boekhandel t 1'1' t' 1' r 't' mtttstAtAghttaftta Pan-Parifir Tinian Central Offices, Honolulu, Hawaii, at the Ocean's Crossroads. PRESIDENT, HON. WALLACE R. FARRINGTON, Governor of Hawaii. ALEXANDER HUME FORD, Director. DR. FRANK F. BUNKER, Executive Secretary. The Pan-Pacific Union, representing the lands about the greatest of oceans, is supported by appropriations from Pacific governments. It works chiefly through the calling of conferences, for the greater advancement of, and cooperati.on among, all the races -and peoples of the Pacific. HONORARY PRESIDENTS Warren G. Harding President of the United States William M. Hughes Prime Minister of Australia W. F. Massey Prime Minister of New Zealand Hsu Shih-chang President of China Arthur Meighen Premier of Canada Prince I. Tokugawa President, House of Peers, Tokyo His Majesty, Rama VI King of Siam HONORARY VICE-PRESIDENTS Charles Evans Hughes Secretary of State, United States Woodrow Wilson Ex-President of the United States Dr. L. S. Rowe Director-General Pan-American Union Yeh Kung Cho Minister of Communications, China Leonard Wood The Governor-General of the Philippines The Premiers of Australian States and of British Columbia The Governor-General of Java. -

Kadavu I Game Fishing Found Exactly What I Was Boat Charters Looking For.” Push Bikes & Scooters Jet Skiis & Watersports Tamarillo’S First Tours Were Led in 1998

Feature “...I needed a destination 100% Fun in Fiji!! with enough tourism infrastructure to support our tours – regular flights, small resorts, expert guides – but no more than that. In Kadavu I game fishing found exactly what I was boat charters looking for.” push bikes & scooters jet skiis & watersports Tamarillo’s first tours were led in 1998. nadi village tours Ratu Bose, a traditional chief in Kadavu, skippered the support boat on the very jet boat rides first tour and still works with Tamarillo scuba diving today as director and operations surfing manager. Tamarillo’s kayaking base and guesthouse is on Ratu Bose’s family settlement, a peninsula of land known as Natubagunu. It was on this very spot that As we paddle along, we regularly stop the first Fijians set foot on Kadavu Island on deserted beaches to rest in the more than 2000 years ago. shade. Tamarillo’s support boat carries the picnic supplies and our guides add “The place-names tell the story,” freshly-caught fish, fruit and coconuts explained Ratu Bose when we visited. picked from the trees above. “Those ancestors of mine would have arrived on this beach hungry and thirsty Today, for afternoon refreshments, we’ve after the long ocean voyage. They found called in to visit the village of Waisomo no stream here so they called the place on Kadavu’s neighbouring Ono Island. Natubagunu, which means something The cakes are cooked, like everything like ‘no water, keep moving’. They carried here, over fire, and I feel like I’m a world on around the point and found a big away from the busy streets of Nadi river flowing out into the bay.