"El Nombre De Podenco:" the Dog As Book in the Prologue of Part II Of

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Universal Quixote: Appropriations of a Literary Icon

THE UNIVERSAL QUIXOTE: APPROPRIATIONS OF A LITERARY ICON A Dissertation by MARK DAVID MCGRAW Submitted to the Office of Graduate Studies of Texas A&M University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Chair of Committee, Eduardo Urbina Committee Members, Paul Christensen Juan Carlos Galdo Janet McCann Stephen Miller Head of Department, Steven Oberhelman August 2013 Major Subject: Hispanic Studies Copyright 2013 Mark David McGraw ABSTRACT First functioning as image based text and then as a widely illustrated book, the impact of the literary figure Don Quixote outgrew his textual limits to gain near- universal recognition as a cultural icon. Compared to the relatively small number of readers who have actually read both extensive volumes of Cervantes´ novel, an overwhelming percentage of people worldwide can identify an image of Don Quixote, especially if he is paired with his squire, Sancho Panza, and know something about the basic premise of the story. The problem that drives this paper is to determine how this Spanish 17th century literary character was able to gain near-univeral iconic recognizability. The methods used to research this phenomenon were to examine the character´s literary beginnings and iconization through translation and adaptation, film, textual and popular iconography, as well commercial, nationalist, revolutionary and institutional appropriations and determine what factors made him so useful for appropriation. The research concludes that the literary figure of Don Quixote has proven to be exceptionally receptive to readers´ appropriative requirements due to his paradoxical nature. The Quixote’s “cuerdo loco” or “wise fool” inherits paradoxy from Erasmus of Rotterdam’s In Praise of Folly. -

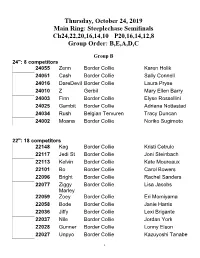

Steeplechase/PSJ Running Order

Thursday, October 24, 2019 Main Ring: Steeplechase Semifinals Ch24,22,20,16,14,10 P20,16,14,12,8 Group Order: B,E,A,D,C Group B 24": 8 competitors 24055 Zenn Border Collie Karen Holik 24051 Cash Border Collie Sally Connell 24016 DareDevil Border Collie Laura Pryse 24010 Z Gerbil Mary Ellen Barry 24003 Finn Border Collie Elyse Rossellini 24025 Gambit Border Collie Adriana Nottestad 24034 Rush Belgian Tervuren Tracy Duncan 24002 Moana Border Collie Noriko Sugimoto 22": 18 competitors 22148 Keg Border Collie Kristi Cetrulo 22117 Jedi St Border Collie Joni Steinbach 22113 Kelvin Border Collie Kate Moureaux 22101 Bo Border Collie Carol Bowers 22096 Bright Border Collie Rachel Sanders 22077 Ziggy Border Collie Lisa Jacobs Marley 22059 Zoey Border Collie Eri Momiyama 22058 Bode Border Collie Janie Harris 22036 Jiffy Border Collie Lexi Brigante 22037 Nile Border Collie Jordan York 22028 Gunner Border Collie Lonny Elson 22027 Unpyo Border Collie Kazuyoshi Tanabe 1 22020 Burst Border Collie Terry Smorch 22002 Mesa Border Collie Brooke Ortale 22122 Smartie Border Collie Sharon Goodwin 22033 Truth Border Collie Alison Carter 22132 Nebraska Border Collie Anna Eifert 22129 Kidd Border Collie Karen Holik 20": 6 competitors 20056 Abby Border Collie Kathy Ketner 20052 Kona Australian Shepherd Jeanette Losey 20049 Kanna Border Collie Masatomo Wakabayashi 20047 Snips Border Collie David Kurtz 20031 Katy Border Collie Fumiko Nitta 20017 Joss Border Collie Linda Johns 16": 11 competitors 16055 Luna All-American Stephanie Spezia 16054 Stripe Shetland Sheepdog -

Cervantes the Cervantes Society of America Volume Xxvi Spring, 2006

Bulletin ofCervantes the Cervantes Society of America volume xxvi Spring, 2006 “El traducir de una lengua en otra… es como quien mira los tapices flamencos por el revés.” Don Quijote II, 62 Translation Number Bulletin of the CervantesCervantes Society of America The Cervantes Society of America President Frederick De Armas (2007-2010) Vice-President Howard Mancing (2007-2010) Secretary-Treasurer Theresa Sears (2007-2010) Executive Council Bruce Burningham (2007-2008) Charles Ganelin (Midwest) Steve Hutchinson (2007-2008) William Childers (Northeast) Rogelio Miñana (2007-2008) Adrienne Martin (Pacific Coast) Carolyn Nadeau (2007-2008) Ignacio López Alemany (Southeast) Barbara Simerka (2007-2008) Christopher Wiemer (Southwest) Cervantes: Bulletin of the Cervantes Society of America Editors: Daniel Eisenberg Tom Lathrop Managing Editor: Fred Jehle (2007-2010) Book Review Editor: William H. Clamurro (2007-2010) Editorial Board John J. Allen † Carroll B. Johnson Antonio Bernat Francisco Márquez Villanueva Patrizia Campana Francisco Rico Jean Canavaggio George Shipley Jaime Fernández Eduardo Urbina Edward H. Friedman Alison P. Weber Aurelio González Diana de Armas Wilson Cervantes, official organ of the Cervantes Society of America, publishes scholarly articles in Eng- lish and Spanish on Cervantes’ life and works, reviews, and notes of interest to Cervantistas. Tw i ce yearly. Subscription to Cervantes is a part of membership in the Cervantes Society of America, which also publishes a newsletter: $20.00 a year for individuals, $40.00 for institutions, $30.00 for couples, and $10.00 for students. Membership is open to all persons interested in Cervantes. For membership and subscription, send check in us dollars to Theresa Sears, 6410 Muirfield Dr., Greensboro, NC 27410. -

TREEING FEIST Official UKC Breed Standard Terrier Group Revised September 1, 2017 ©Copyright 2000, United Kennel Club

TREEING FEIST Official UKC Breed Standard Terrier Group Revised September 1, 2017 ©Copyright 2000, United Kennel Club allow the dog to move quickly and with agility in rough terrain. The head is blocky, with a broad skull, a moderate stop, and a strong muzzle. The tail is straight, set on as a natural extension of the topline, and may be natural or docked. The coat is short and smooth. The Treeing Feist should be evaluated as a working dog, and exaggerations or faults should be penalized in proportion to how much they interfere with the dog’s ability to work. Scars should neither be penalized nor regarded as proof of a dog’s working abilities. CHARACTERISTICS Treeing Feists are used most frequently to hunt squirrel, raccoon, and opossum. They hunt using both sight and scent and are extremely alert dogs. On track, they are The goals and purposes of this breed standard include: virtually silent. to furnish guidelines for breeders who wish to maintain the quality of their breed and to improve it; to advance this breed to a state of similarity throughout the world; and to act as a guide for judges. Breeders and judges have the responsibility to avoid any conditions or exaggerations that are detrimental to the health, welfare, essence and soundness of this breed, and must take the responsibility to see that these are not perpetuated. Any departure from the following should be considered a fault, and the seriousness with which the fault should be regarded should be in exact proportion to its degree and its effect upon the health and welfare of the dog and on the dog’s ability to perform its traditional work. -

Don Quijote in English

Tilting at Windmills: Don Quijote in English _________________________________________ Michael J. McGrath rinted on the inside jacket of Edith Grossman’s 2003 transla- tion of Don Quijote is the following statement: “Unless you read PSpanish, you have never read Don Quixote.” For many people, the belief that a novel should be read in its original language is not contro- vertible. The Russian writer Dostoevsky learned Spanish just to be able to read Don Quijote. Lord Byron described his reading of the novel in Spanish as “a pleasure before which all others vanish” (Don Juan 14.98). Unfortunately, there are many readers who are unable to read the novel in its original language, and those who depend upon an English transla- tion may read a version that is linguistically and culturally quite different from the original. In his article “Traduttori Traditori: Don Quixote in English,” John Jay Allen cites the number of errors he encountered in different translations as a reason for writing the article. In addition, ac- cording to Allen, literary scholarship runs the risk of being skewed as a result of the translator’s inability to capture the text’s original meaning: I think that we Hispanists tend to forget that the overwhelming ma- jority of comments on Don Quixote by non-Spaniards—novelists, theoreticians of literature, even comparatists—are based upon read- ings in translation, and I, for one, had never considered just what this might mean for interpretation. The notorious difficulty in es- tablishing the locus of value in Don Quixote should alert us to the tremendous influence a translator may have in tipping the balance in what is obviously a delicate equilibrium of ambiguity and multi- valence. -

Event Fee Worksheet Event Fee Worksheet

Event Fee Worksheet Event Fee Worksheet Event Date UKC Club I.D. # Event Date UKC Club I.D. # Club Name Club Name 1. HAVE LICENSE FEES BEEN PAID FOR THIS EVENT? 1. HAVE LICENSE FEES BEEN PAID FOR THIS EVENT? If yes, skip to section 2. If no, determine the amount of license fees still owed. If yes, skip to section 2. If no, determine the amount of license fees still owed. STANDARD HUNT LICENSE STANDARD HUNT LICENSE (Coonhound, Beagle, Cur/Feist) $25 K (Coonhound, Beagle, Cur/Feist) $25 K COMBINED HUNT LICENSE COMBINED HUNT LICENSE (Coonhound, Cur/Feist) $40 K (Coonhound, Cur/Feist) $40 K SLAM EVENT HUNT LICENSE $25 K SLAM EVENT HUNT LICENSE $25 K BENCH SHOW LICENSE BENCH SHOW LICENSE (Coonhound, Beagle, Cur/Feist) $17 K (Coonhound, Beagle, Cur/Feist) $17 K WATER RACE (Coonhound only) $17 K WATER RACE (Coonhound only) $17 K FIELD TRIAL (Coonhound only) $17 K FIELD TRIAL (Coonhound only) $17 K TREEING CONTEST (Cur/Feist only) $17 K TREEING CONTEST (Cur/Feist only) $17 K YEP or YOUTH CHAMPIONSHIP HUNT (NO FEE) YEP or YOUTH CHAMPIONSHIP HUNT (NO FEE) YEP or YOUTH CHAMPIONSHIP SHOW (NO FEE) YEP or YOUTH CHAMPIONSHIP SHOW (NO FEE) TOTAL LICENSE FEES $________ TOTAL LICENSE FEES $________ 2. RECORDING FEES 2. RECORDING FEES HUNT RECORDING FEE ________ dogs x $2 = ________ HUNT RECORDING FEE ________ dogs x $2 = ________ SHOW RECORDING FEE ________ dogs x $2 = ________ SHOW RECORDING FEE ________ dogs x $2 = ________ WATER RACE RECORDING FEE ________ dogs x $2 = ________ WATER RACE RECORDING FEE ________ dogs x $2 = ________ FIELD TRIAL RECORDING FEE ________ dogs x $2 = ________ FIELD TRIAL RECORDING FEE ________ dogs x $2 = ________ TREEING CONTEST RECORDING FEE ________ dogs x $2 = ________ TREEING CONTEST RECORDING FEE ________ dogs x $2 = ________ (Cur/Feist only) (Cur/Feist only) YEP or YOUTH CHAMPIONSHIP HUNT (NO FEE) YEP or YOUTH CHAMPIONSHIP HUNT (NO FEE) TOTAL RECORDING FEES $________ TOTAL RECORDING FEES $________ 3. -

Best in Grooming Best in Show

Best in Grooming Best in Show crownroyaleltd.net About Us Crown Royale was founded in 1983 when AKC Breeder & Handler Allen Levine asked his friend Nick Scodari, a formulating chemist, to create a line of products that would be breed specific and help the coat to best represent the breed standard. It all began with the Biovite shampoos and Magic Touch grooming sprays which quickly became a hit with show dog professionals. The full line of Crown Royale grooming products followed in Best in Grooming formulas to meet the needs of different coat types. Best in Show Current owner, Cindy Silva, started work in the office in 1996 and soon found herself involved in all aspects of the company. In May 2006, Cindy took full ownership of Crown Royale Ltd., which continues to be a family run business, located in scenic Phillipsburg, NJ. Crown Royale Ltd. continues to bring new, innovative products to professional handlers, groomers and pet owners worldwide. All products are proudly made in the USA with the mission that there is no substitute for quality. Table of Contents About Us . 2 How to use Crown Royale . 3 Grooming Aids . .3 Biovite Shampoos . .4 Shampoos . .5 Conditioners . .6 Finishing, Grooming & Brushing Sprays . .7 Dog Breed & Coat Type . 8-9 Powders . .10 Triple Play Packs . .11 Sporting Dog . .12 Dilution Formulas: Please note when mixing concentrate and storing them for use other than short-term, we recommend mixing with distilled water to keep the formulas as true as possible due to variation in water make-up throughout the USA and international. -

Cur & Feist Litter Registration Application

CUR & FEIST LITTER REGISTRATION APPLICATION Please allow 4 to 6 weeks for processing. UKC ® is not responsible for errors caused by illegible handwriting. Incomplete applications may result in processing delays. The litter must be registered before it reaches one year of age. Both the Sire and Dam must be permanently registered with UKC in order to register a litter. You can register this litter online at UKCdogs.com Step 1 - Litter Information - Complete the following information: Total number of living male and female puppies in the Litter, Date of Breeding and Date of Birth. Date of Breeding ____________ / ____________ / ____________ Date of Birth ____________ / ____________ / ____________ month day year month day year NOTE: Purebred litters may contain X-Bred pups not eligible for purebred status due to a breed standard disqualification. CUR Options FEIST Options # of Purebred Males _________ # of Purebred Females _______ K Black Mouth Cur K Treeing Cur K Mountain Feist # of X-Bred Males ___________ # of X-Bred Females _________ K Mountain Cur K Treeing Tennessee Brindle K Treeing Feist TOTAL # Males _____________ TOTAL # Females ___________ K Stephen’s Cur K X-Bred Cur K X-Bred Feist Normal Gestation Period is 63 days. Step 2 - Sire Information Step 3 - Dam Information UKC # _____________________________ UKC # _____________________________ Was Frozen Semen Used? K Yes K No Date Collected for Freezing__________________________ Registered Name of Dam _______________________________________________________________ Registered Name of -

Product Catalog

DOG COUNTRY Whether protecting, hunting or herding, dogs for two centuries were essential to settlers making new homes in the American wilderness. By Gregory LeFever English Pointers© by Joseph Sulkowski The small wolf-like animal known as the Indian dog must have stared in awe from the forest- ed Atlantic shoreline at the dawn of the 17th century as the dogs of Europe—the powerful mastiffs, greyhounds and bloodhounds—first bounded down the gangplanks of sailing ships and onto the New World’s sandy shores. The fate of these two types of dogs would mirror those of their human counterparts as the Europeans and their descendants pushed westward toward another ocean—conquering frontier after frontier—while Native Americans nearly vanished from the landscape. It would take two hundred years at the hands of the new settlers, but eventually the little Indian dog would be deemed extinct. Meanwhile, dozens of new breeds of dog derived mostly from European strains excelling at hunting and herding would establish themselves in America and prove vital to every major exploration and homesteading venture from the Atlantic to the Pacific. The stories of dogs in the settling of America tell of the same uncompromising bravery, loyalty and companionship that dog lovers cherish today. Surely, European immigrants could have settled America without dogs, but it’s difficult to imagine how. LONG TREK TO A NEW LAND No one knows for sure where dogs originated or how they first came to America. Best guesses 30 are that the earliest dogs were from southern China about 40,000 years ago and that dogs crossed the Bering land bridge from Siberia to North America some 17,000 years ago. -

Official Ukc Conformation Rulebook

OFFICIAL UKC CONFORMATION RULEBOOK Effective January 1, 2011 Table of Contents Regulations Governing UKC ® Licensed Conformation Shows ..............................................3 Regulations Governing Jurisdiction .................................................................3 UKC ® Licensed Who May Offer Conformation Events .......................3 Definitions ...................................................................3 Conformation Shows General Rules .............................................................6 *Effective January 1, 2011 Dog Temperament and Behavior ...............................8 UKC is the trademark of the Use of Alcohol and Illegal Drugs at Events ...............9 United Kennel Club, Inc. Misconduct and Discipline .......................................10 located in Kalamazoo, MI. Entering a UKC Event ..............................................17 The use of the initials UKC in association with any other Judging Schedule ....................................................20 registry would be in violation Judge Changes ........................................................20 of the registered trademark. Notify the United Kennel United Kennel Club Policy on Show Site Club, 100 E Kilgore Rd, Kalamazoo MI 49002-5584, Changes and Canceled Events ............................21 should you become aware of such a violation. Regular Licensed Classes ........................................23 Dogs That May Compete in Altered I. Jurisdiction. The following rules and regula - Licensed Classes ..................................................30 -

Handling of Translations

humanities Article A Quixotic Endeavor: The Translator’s Role and Responsibility in Bridging Divides in the (Mis)handling of Translations Cesar Osuna Department of English, College of Humanities, California State University, Northridge, CA 91330, USA; [email protected] Received: 18 September 2020; Accepted: 12 October 2020; Published: 15 October 2020 Abstract: Miguel de Cervantes’ Don Quixote de la Mancha, one of the most translated works of literature, has seen over twenty different English translations in the 406 years since its first translation. Some translators remain more faithful than others. In a world where there should be an erasure of the lines that separate cultures, the lines are, in fact, deepening. John Felstiner explains in his book, Translating Neruda: The Way to Macchu Picchu, that “a translation converts strangeness into likeness, and yet in doing so may bring home to us the strangeness of the original... Doing without translations, then, might confine us to a kind of solipsistic cultural prison” (Felstiner 5). By looking at translations of Don Quixote de la Mancha, this paper examines how the inaccuracies and misrepresentations by translators deepen the lines that divide cultures. Textual edits are made, plots are altered, and additions are made to the text. These differences might seem inconsequential to the reader, but the reverberations of such changes have tremendous consequences. While there may not be a perfect translation, editors and translators must aim towards that objective. Instead, the translators appropriate the work, often styling or rewriting it in order to mold it to fit their own visions of what the work should be. -

Dog Breeds Volume 5

Dog Breeds - Volume 5 A Wikipedia Compilation by Michael A. Linton Contents 1 Russell Terrier 1 1.1 History ................................................. 1 1.1.1 Breed development in England and Australia ........................ 1 1.1.2 The Russell Terrier in the U.S.A. .............................. 2 1.1.3 More ............................................. 2 1.2 References ............................................... 2 1.3 External links ............................................. 3 2 Saarloos wolfdog 4 2.1 History ................................................. 4 2.2 Size and appearance .......................................... 4 2.3 See also ................................................ 4 2.4 References ............................................... 4 2.5 External links ............................................. 4 3 Sabueso Español 5 3.1 History ................................................ 5 3.2 Appearance .............................................. 5 3.3 Use .................................................. 7 3.4 Fictional Spanish Hounds ....................................... 8 3.5 References .............................................. 8 3.6 External links ............................................. 8 4 Saint-Usuge Spaniel 9 4.1 History ................................................. 9 4.2 Description .............................................. 9 4.2.1 Temperament ......................................... 10 4.3 References ............................................... 10 4.4 External links