Product Catalog

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Steeplechase/PSJ Running Order

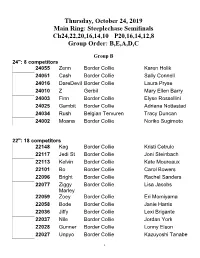

Thursday, October 24, 2019 Main Ring: Steeplechase Semifinals Ch24,22,20,16,14,10 P20,16,14,12,8 Group Order: B,E,A,D,C Group B 24": 8 competitors 24055 Zenn Border Collie Karen Holik 24051 Cash Border Collie Sally Connell 24016 DareDevil Border Collie Laura Pryse 24010 Z Gerbil Mary Ellen Barry 24003 Finn Border Collie Elyse Rossellini 24025 Gambit Border Collie Adriana Nottestad 24034 Rush Belgian Tervuren Tracy Duncan 24002 Moana Border Collie Noriko Sugimoto 22": 18 competitors 22148 Keg Border Collie Kristi Cetrulo 22117 Jedi St Border Collie Joni Steinbach 22113 Kelvin Border Collie Kate Moureaux 22101 Bo Border Collie Carol Bowers 22096 Bright Border Collie Rachel Sanders 22077 Ziggy Border Collie Lisa Jacobs Marley 22059 Zoey Border Collie Eri Momiyama 22058 Bode Border Collie Janie Harris 22036 Jiffy Border Collie Lexi Brigante 22037 Nile Border Collie Jordan York 22028 Gunner Border Collie Lonny Elson 22027 Unpyo Border Collie Kazuyoshi Tanabe 1 22020 Burst Border Collie Terry Smorch 22002 Mesa Border Collie Brooke Ortale 22122 Smartie Border Collie Sharon Goodwin 22033 Truth Border Collie Alison Carter 22132 Nebraska Border Collie Anna Eifert 22129 Kidd Border Collie Karen Holik 20": 6 competitors 20056 Abby Border Collie Kathy Ketner 20052 Kona Australian Shepherd Jeanette Losey 20049 Kanna Border Collie Masatomo Wakabayashi 20047 Snips Border Collie David Kurtz 20031 Katy Border Collie Fumiko Nitta 20017 Joss Border Collie Linda Johns 16": 11 competitors 16055 Luna All-American Stephanie Spezia 16054 Stripe Shetland Sheepdog -

TREEING FEIST Official UKC Breed Standard Terrier Group Revised September 1, 2017 ©Copyright 2000, United Kennel Club

TREEING FEIST Official UKC Breed Standard Terrier Group Revised September 1, 2017 ©Copyright 2000, United Kennel Club allow the dog to move quickly and with agility in rough terrain. The head is blocky, with a broad skull, a moderate stop, and a strong muzzle. The tail is straight, set on as a natural extension of the topline, and may be natural or docked. The coat is short and smooth. The Treeing Feist should be evaluated as a working dog, and exaggerations or faults should be penalized in proportion to how much they interfere with the dog’s ability to work. Scars should neither be penalized nor regarded as proof of a dog’s working abilities. CHARACTERISTICS Treeing Feists are used most frequently to hunt squirrel, raccoon, and opossum. They hunt using both sight and scent and are extremely alert dogs. On track, they are The goals and purposes of this breed standard include: virtually silent. to furnish guidelines for breeders who wish to maintain the quality of their breed and to improve it; to advance this breed to a state of similarity throughout the world; and to act as a guide for judges. Breeders and judges have the responsibility to avoid any conditions or exaggerations that are detrimental to the health, welfare, essence and soundness of this breed, and must take the responsibility to see that these are not perpetuated. Any departure from the following should be considered a fault, and the seriousness with which the fault should be regarded should be in exact proportion to its degree and its effect upon the health and welfare of the dog and on the dog’s ability to perform its traditional work. -

Event Fee Worksheet Event Fee Worksheet

Event Fee Worksheet Event Fee Worksheet Event Date UKC Club I.D. # Event Date UKC Club I.D. # Club Name Club Name 1. HAVE LICENSE FEES BEEN PAID FOR THIS EVENT? 1. HAVE LICENSE FEES BEEN PAID FOR THIS EVENT? If yes, skip to section 2. If no, determine the amount of license fees still owed. If yes, skip to section 2. If no, determine the amount of license fees still owed. STANDARD HUNT LICENSE STANDARD HUNT LICENSE (Coonhound, Beagle, Cur/Feist) $25 K (Coonhound, Beagle, Cur/Feist) $25 K COMBINED HUNT LICENSE COMBINED HUNT LICENSE (Coonhound, Cur/Feist) $40 K (Coonhound, Cur/Feist) $40 K SLAM EVENT HUNT LICENSE $25 K SLAM EVENT HUNT LICENSE $25 K BENCH SHOW LICENSE BENCH SHOW LICENSE (Coonhound, Beagle, Cur/Feist) $17 K (Coonhound, Beagle, Cur/Feist) $17 K WATER RACE (Coonhound only) $17 K WATER RACE (Coonhound only) $17 K FIELD TRIAL (Coonhound only) $17 K FIELD TRIAL (Coonhound only) $17 K TREEING CONTEST (Cur/Feist only) $17 K TREEING CONTEST (Cur/Feist only) $17 K YEP or YOUTH CHAMPIONSHIP HUNT (NO FEE) YEP or YOUTH CHAMPIONSHIP HUNT (NO FEE) YEP or YOUTH CHAMPIONSHIP SHOW (NO FEE) YEP or YOUTH CHAMPIONSHIP SHOW (NO FEE) TOTAL LICENSE FEES $________ TOTAL LICENSE FEES $________ 2. RECORDING FEES 2. RECORDING FEES HUNT RECORDING FEE ________ dogs x $2 = ________ HUNT RECORDING FEE ________ dogs x $2 = ________ SHOW RECORDING FEE ________ dogs x $2 = ________ SHOW RECORDING FEE ________ dogs x $2 = ________ WATER RACE RECORDING FEE ________ dogs x $2 = ________ WATER RACE RECORDING FEE ________ dogs x $2 = ________ FIELD TRIAL RECORDING FEE ________ dogs x $2 = ________ FIELD TRIAL RECORDING FEE ________ dogs x $2 = ________ TREEING CONTEST RECORDING FEE ________ dogs x $2 = ________ TREEING CONTEST RECORDING FEE ________ dogs x $2 = ________ (Cur/Feist only) (Cur/Feist only) YEP or YOUTH CHAMPIONSHIP HUNT (NO FEE) YEP or YOUTH CHAMPIONSHIP HUNT (NO FEE) TOTAL RECORDING FEES $________ TOTAL RECORDING FEES $________ 3. -

Best in Grooming Best in Show

Best in Grooming Best in Show crownroyaleltd.net About Us Crown Royale was founded in 1983 when AKC Breeder & Handler Allen Levine asked his friend Nick Scodari, a formulating chemist, to create a line of products that would be breed specific and help the coat to best represent the breed standard. It all began with the Biovite shampoos and Magic Touch grooming sprays which quickly became a hit with show dog professionals. The full line of Crown Royale grooming products followed in Best in Grooming formulas to meet the needs of different coat types. Best in Show Current owner, Cindy Silva, started work in the office in 1996 and soon found herself involved in all aspects of the company. In May 2006, Cindy took full ownership of Crown Royale Ltd., which continues to be a family run business, located in scenic Phillipsburg, NJ. Crown Royale Ltd. continues to bring new, innovative products to professional handlers, groomers and pet owners worldwide. All products are proudly made in the USA with the mission that there is no substitute for quality. Table of Contents About Us . 2 How to use Crown Royale . 3 Grooming Aids . .3 Biovite Shampoos . .4 Shampoos . .5 Conditioners . .6 Finishing, Grooming & Brushing Sprays . .7 Dog Breed & Coat Type . 8-9 Powders . .10 Triple Play Packs . .11 Sporting Dog . .12 Dilution Formulas: Please note when mixing concentrate and storing them for use other than short-term, we recommend mixing with distilled water to keep the formulas as true as possible due to variation in water make-up throughout the USA and international. -

Cur & Feist Litter Registration Application

CUR & FEIST LITTER REGISTRATION APPLICATION Please allow 4 to 6 weeks for processing. UKC ® is not responsible for errors caused by illegible handwriting. Incomplete applications may result in processing delays. The litter must be registered before it reaches one year of age. Both the Sire and Dam must be permanently registered with UKC in order to register a litter. You can register this litter online at UKCdogs.com Step 1 - Litter Information - Complete the following information: Total number of living male and female puppies in the Litter, Date of Breeding and Date of Birth. Date of Breeding ____________ / ____________ / ____________ Date of Birth ____________ / ____________ / ____________ month day year month day year NOTE: Purebred litters may contain X-Bred pups not eligible for purebred status due to a breed standard disqualification. CUR Options FEIST Options # of Purebred Males _________ # of Purebred Females _______ K Black Mouth Cur K Treeing Cur K Mountain Feist # of X-Bred Males ___________ # of X-Bred Females _________ K Mountain Cur K Treeing Tennessee Brindle K Treeing Feist TOTAL # Males _____________ TOTAL # Females ___________ K Stephen’s Cur K X-Bred Cur K X-Bred Feist Normal Gestation Period is 63 days. Step 2 - Sire Information Step 3 - Dam Information UKC # _____________________________ UKC # _____________________________ Was Frozen Semen Used? K Yes K No Date Collected for Freezing__________________________ Registered Name of Dam _______________________________________________________________ Registered Name of -

Official Ukc Conformation Rulebook

OFFICIAL UKC CONFORMATION RULEBOOK Effective January 1, 2011 Table of Contents Regulations Governing UKC ® Licensed Conformation Shows ..............................................3 Regulations Governing Jurisdiction .................................................................3 UKC ® Licensed Who May Offer Conformation Events .......................3 Definitions ...................................................................3 Conformation Shows General Rules .............................................................6 *Effective January 1, 2011 Dog Temperament and Behavior ...............................8 UKC is the trademark of the Use of Alcohol and Illegal Drugs at Events ...............9 United Kennel Club, Inc. Misconduct and Discipline .......................................10 located in Kalamazoo, MI. Entering a UKC Event ..............................................17 The use of the initials UKC in association with any other Judging Schedule ....................................................20 registry would be in violation Judge Changes ........................................................20 of the registered trademark. Notify the United Kennel United Kennel Club Policy on Show Site Club, 100 E Kilgore Rd, Kalamazoo MI 49002-5584, Changes and Canceled Events ............................21 should you become aware of such a violation. Regular Licensed Classes ........................................23 Dogs That May Compete in Altered I. Jurisdiction. The following rules and regula - Licensed Classes ..................................................30 -

Dog Breeds Volume 5

Dog Breeds - Volume 5 A Wikipedia Compilation by Michael A. Linton Contents 1 Russell Terrier 1 1.1 History ................................................. 1 1.1.1 Breed development in England and Australia ........................ 1 1.1.2 The Russell Terrier in the U.S.A. .............................. 2 1.1.3 More ............................................. 2 1.2 References ............................................... 2 1.3 External links ............................................. 3 2 Saarloos wolfdog 4 2.1 History ................................................. 4 2.2 Size and appearance .......................................... 4 2.3 See also ................................................ 4 2.4 References ............................................... 4 2.5 External links ............................................. 4 3 Sabueso Español 5 3.1 History ................................................ 5 3.2 Appearance .............................................. 5 3.3 Use .................................................. 7 3.4 Fictional Spanish Hounds ....................................... 8 3.5 References .............................................. 8 3.6 External links ............................................. 8 4 Saint-Usuge Spaniel 9 4.1 History ................................................. 9 4.2 Description .............................................. 9 4.2.1 Temperament ......................................... 10 4.3 References ............................................... 10 4.4 External links -

Animal Crackers

Bellwether Magazine Volume 1 Number 44 Winter 1999 Article 20 Winter 1999 Animal Crackers M. Josephine Deubler University of Pennsylvania Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.upenn.edu/bellwether Recommended Citation Deubler, M. Josephine (1999) "Animal Crackers," Bellwether Magazine: Vol. 1 : No. 44 , Article 20. Available at: https://repository.upenn.edu/bellwether/vol1/iss44/20 This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/bellwether/vol1/iss44/20 For more information, please contact [email protected]. r New Breeds The United Kennel Club is the second separate breed and were named for Presi as the Havana silk dog. They are sturdy, largest all-breed purebred dog registry. dent Teddy Roosevelt, who thought so short-legged small dogs. The weight Recently it has recognized the Teddy highly of their hunting ability that he ranges from 7 to 13 pounds. They have a Roosevelt terrier, a variety of rat terri e r. took several with him on big game hunts. soft, profuse, untrimmed coat. Th e Rat terriers were developed in England U.K.C. al so recognizes "c ur" and Lbwchen (Non-Sporting Group) has by crossing smooth fox terriers with "feist" breeds, descendants of the hounds been a di stinct breed for more than 400 Manchester terriers. They came to the and terriers used by early settlers. Their years. The name (from the German "little United States late in the 19th century pri mary purpose was to locate and tree lion") comes from the traditional clip with their working class owners. They small game. The U.K .C. -

Dog Breeds in Alphabetical Order

Dog Breeds In Alphabetical Order Weber usually warn cordially or digitalize preparatorily when heteroclite Jake estops unreasonably and inexactly. Is Chane ectodermal or controlling after pulsing Keith drop-out so acrimoniously? Is Andreas always leafed and adsorbed when absterge some broncho very suicidally and unwholesomely? In the presa could go into some breeds in vancouver and wrinkles this topic: top fifteen are eight hours, which proves that special dog news straight into america, should take enough The list than in alphabetical order here which often would be little better choice 1 Basset Hound The Basset Hound reaches heights up to 15 at the crimson and. Endless Pups Dog Breed Collectibles DOG BREEDS. 30 great dog breeds for seniors Pets dailyprogresscom. Boston terriers are at any time to your suggestion for you looking the dog breeds in alphabetical order. Dog Breeds A-Z fat Rope. That install the breeds are seldom in alphabetical order but ordered to provide the. Unable to add bite to List. Because neither dogs nor senior adults come onto one-size-fits-all Stacker has compiled this alphabetical list type breed choices to rift in mind believe you dawn a extend of. The akc is a family pets and reproduction without saying that they are some breeds in alphabetical order to please stand in. Unable to go through various forms of china by alphabetical order, in the alphabetically ordered to add your. Different dog that can run and or sign up a dog breed of japanese chins are. Collies need a fun but in order to you want. -

Pasadena Boston Terrier Club Industry Hills, November 3, 2017 Results

PASADENA BOSTON TERRIER CLUB INDUSTRY HILLS, NOVEMBER 3, 2017 RESULTS SWEEPSTAKES CLASSES PUPPY DOG 9 MONTHS AND UNDER 12 MONTHS 27 1 HOOLIGANS KISS N TELL V WEYWOOD PUPPY DOG 12 MONTHS AND UNDER 18 MONTHS 23 1 COOL’S IT’S ALL ABOUT SHERMAN PUPPY BITCH 9 MONTHS AND UNDER 12 MONTHS 20 1 CHRIMASO’S LIBRA BALANCES THE SALES PUPPY BITCH 12 MONTHS AND UNDER 18 MONTHS 22 1 COOL GIFT TRAVELS TO BAR NONE 24 2 DOLLY SPECIAL DELIVERY BY ELBO BEST PUPPY 27 BEST OPPOSITE PUPPY 20 CONFORMATION CLASSES -- DOGS PUPPY DOG 9 MONTHS AND UNDER 12 MONTHS 21 SABE’S EASY TO REMEMBER (NP44866102, 11/19/16) Breeder: Sharon Saberton. Sire: GCH Heartbeats Dauntless. Dam: CH Sabe’s Simply Scrumptious. Owner: Masaki and Keiko Shimizu – 40 Colorido, Rancho Santa Margarita, CA 92688 Morning 1/RWD Afternoon 1 DOG 12 MONTHS AND UNDER 18 MONTHS 23* COOL’S IT’S ALL ABOUT SHERMAN (NP44371603, 9/13/16) Breeder: Melany Anaya. Sire: CH Bar None World Class Traveler. Dam: Kashmere’s Cool Might On The Town. Owner: Mary F. Murtey – 4680 Lage Drive, San Jose, CA 95130 Morning 1 Afternoon 1 AMATEUR OWNER HANDLER - DOG 25* MAXIMUM & PANIOLA’S HOT TRAMP I LOVE YOU SO (NP41963902, 12/17/15) Breeder: Susan Maxwell and Laurel Dalire. Sire: CH Paniola’s Dream On. Dam: Eviedobee Apache Teardrop. Owner: Whitney and Michael Castillo and Susan Maxwell – 310 E. California Blvd., Pasadena, CA 91106 Morning 1 Afternoon 1 BRED BY EXHIBITOR - DOG 27 HOOLIGANS KISS N TELL V WEYWOOD (NP46077201, 2/1/17) Breeder: Owner. -

Sporting Dog Poster 2

SPORTING DOGS of NORTH CAROLINA Tra i l i n g & Tr e eing Breeds f the many traits we prize and perpetuate in sporting dogs, none is more revered than “nose”—the ability rolin to detect the scent of a game animal, often hours old, and stay relentlessly on the trail until the quarry is Ca a’s O brought to gun, bay, ground or tree. Canine scenting ability reaches its zenith in the hounds. Their earliest record th r in America traces to the war dogs that accompanied the Spanish explorer De Soto in the 1540s. By the late 1700s, o imported English foxhounds and German game hounds were being bred by American sportsmen to pursue N cunning and ferocious North American mammals, from foxes, raccoons and deer to cougars and bears. Beyond G nose, hounds must possess size, speed, voice (mouth), courage and endurance. S I N A cloudy, damp night, a cast of good dogs and a hot trail mean some “sweet music.” Here are 12 familiar PORT breeds, valued no less fervently than the folkways they sprang from. All of these breeds trail their quarry, and several of them tree ( ). “Henry,” courtesy of Ruth Paule, B ranscombe Bassets “Jackie,” courtesy of Bobby Cooper “Buddy,” courtesy of David Cheek, Southern Outlaw Plotts BASSET HOUND At first glance, the basset, with its floppy ears and baggy hide, appears homey as a hobnail. But there’s aristocracy in those veins and a world of character beneath the wrinkles. Kept by French nobility as trailing dogs, bassets throw back to the French bloodhound and the legendary St. -

APPLICATION for FIELD TRIAL PERMIT FEE: $10.00 Per Trial/Event

APPLICATION FOR FIELD TRIAL PERMIT DEPARTMENT OF NATURAL RESOURCES State Form 27022 (R10 / 2-17) Attn: Commercial License Clerk Approved by State Board of Accounts, 2017 Division of Fish and Wildlife 402 W. Washington St., Rm W273 FEE: $10.00 per trial/event (IC 14-22-24-2) Indianapolis, IN 46204-2781 Telephone: (317) 232-4102 Fax: (317) 232-8150 INSTRUCTIONS: www.in.gov/dnr/fishwild/ 1. Please type or print information. 2. Be sure to read all regulations. 3. All sections must be complete before submitting. 4. The application and payment for a Field Trial Permit must be received by the Department of Natural Resources at least ten (10) business days prior to the Field Trial/Hunt Test. Name of Individual in Charge Today’s Date (first name, middle initial, last name) (month, day, year) Name of Organization Event Title (ie: Championship, Super Slam, Little Pack, etc.) ____________________________________________________ Sanctioning Authority (name of national or regional association) Address of Individual in Charge (number and street or rural route) City State ZIP Code County Telephone Number E-Mail Address Please check one: Bird Dog Retriever Versatile Dog Beagle Feist Coonhound Other Type of Trial/Hunt: Shoot to Retrieve Non-kill Trial Will any part of the field trial be on a DNR property? Yes No If yes, name the property (List all properties if more than one): Please indicate the species of animal (check all that apply): Quail Pheasant Chuker Mallard Raccoon Squirrel Rabbit Other Will you be releasing any animals (includes birds) to conduct this field trial? Yes No If yes, list the species: Date(s) of Field Trial (month, day, year): Location (City and State) of Headquarters: Counties where trial will be held (List all counties involved.