This PDF Is a Selection from an Out-Of-Print Volume from the National Bureau of Economic Research Volume Title: the Internationa

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Bibliography

BIbLIOGRAPHY 2016 AFI Annual Report. (2017). Alliance for Financial Inclusion. Retrieved July 31, 2017, from https://www.afi-global.org/sites/default/files/publica- tions/2017-05/2016%20AFI%20Annual%20Report.pdf. A Law of the Abolition of Currencies in a Small Denomination and Rounding off a Fraction, July 15, 1953, Law No.60 (Shōgakutsūka no seiri oyobi shiharaikin no hasūkeisan ni kansuru hōritsu). Retrieved April 11, 2017, from https:// web.archive.org/web/20020628033108/http://www.shugiin.go.jp/itdb_ housei.nsf/html/houritsu/01619530715060.htm. About PBC. (2018, August 21). The People’s Bank of China. Retrieved August 21, 2018, from http://www.pbc.gov.cn/english/130712/index.html. About Us. Alliance for Financial Inclusion. Retrieved July 31, 2017, from https:// www.afi-global.org/about-us. AFI Official Members. Alliance for Financial Inclusion. Retrieved July 31, 2017, from https://www.afi-global.org/sites/default/files/inlinefiles/AFI%20 Official%20Members_8%20February%202018.pdf. Ahamed, L. (2009). Lords of Finance: The Bankers Who Broke the World. London: Penguin Books. Alderman, L., Kanter, J., Yardley, J., Ewing, J., Kitsantonis, N., Daley, S., Russell, K., Higgins, A., & Eavis, P. (2016, June 17). Explaining Greece’s Debt Crisis. The New York Times. Retrieved January 28, 2018, from https://www.nytimes. com/interactive/2016/business/international/greece-debt-crisis-euro.html. Alesina, A. (1988). Macroeconomics and Politics (S. Fischer, Ed.). NBER Macroeconomics Annual, 3, 13–62. Alesina, A. (1989). Politics and Business Cycles in Industrial Democracies. Economic Policy, 4(8), 57–98. © The Author(s) 2018 355 R. Ray Chaudhuri, Central Bank Independence, Regulations, and Monetary Policy, https://doi.org/10.1057/978-1-137-58912-5 356 BIBLIOGRAPHY Alesina, A., & Grilli, V. -

147 Chapter 5 South Africa's Experience with Inflation: A

147 CHAPTER 5 SOUTH AFRICA’S EXPERIENCE WITH INFLATION: A CENTRAL BANK PERSPECTIVE 5.1 Introduction Although a country’s experience with inflation can be reviewed from different perspectives (e.g. the government, the statistical agency responsible for recording inflation, producers, consumers or savers), this chapter reviews South Africa’s experience with inflation from the perspective of the SA Reserve Bank. The SA Reserve Bank was chosen because this study focuses on inflation from a monetary perspective. Reliable inflation data for South Africa are published as far back as 192153, co-inciding with the establishment of the SA Reserve Bank, although rudimentary data on price levels are available as far back as 1895. South Africa’s problems with accelerating inflation since the 1970s are well documented (see for instance De Kock, 1981; De Kock, 1984; Republiek van Suid-Afrika, 1985; Rupert, 1974a; Rupert, 1974b; or Stals, 1989), but various parts (or regions) of what constitutes today the Republic of South Africa have experienced problems with inflation, rising prices or currency depreciation well before 1921. The first example of early inflation in South Africa was caused by currency depreciation. At the time of the second British annexation of the Cape in 1806, the Dutch riksdaalder (“riksdollar”) served as the major local currency in circulation. During the tenure of Caledon, Governor of the Cape Colony from 1807 to 1811, and Cradock, Governor from 1811 to 1814, riksdollar notes in circulation were increased by nearly 50 per cent (Engelbrecht, 1987: 29). As could be expected under circumstances of increasing currency in circulation, the value of the riksdollar in comparison to the British pound sterling and in terms of its purchasing power declined from 4 shillings in 1806 to 1 shilling and 5½ pennies in 1825 (or 53 Tables A1 to C1 in Appendices A to C highlight South Africa’s experience with inflation, as measured by changes in the CPI since 1921. -

This PDF Is a Selection from an Out-Of-Print Volume from the National Bureau of Economic Research

This PDF is a selection from an out-of-print volume from the National Bureau of Economic Research Volume Title: The International Gold Standard Reinterpreted, 1914-1934 Volume Author/Editor: William Adams Brown, Jr. Volume Publisher: NBER Volume ISBN: 0-87014-036-1 Volume URL: http://www.nber.org/books/brow40-1 Publication Date: 1940 Chapter Title: Book IV, Part I: The Nature of the Disintegration Chapter Author: William Adams Brown, Jr. Chapter URL: http://www.nber.org/chapters/c5948 Chapter pages in book: (p. 1050 - 1069) Disintegration the of Xature The I Disintegration, FOUR BOOK CHAPTER 29 The Major Characteristics of the Period following September 1931 TheGold Standard (Amendment) Act of September 21, ended the brief history of the gold bullion standard in Great Britain. It inaugurated a period during which the pound sterling declined in terms of the dollar, the franc, and all other currencies which, through the mechanism of the international gold standard or otherwise, were kept in an un- changed and stable relation to these two currencies and to one another. The Concept of the Breakup of the Nucleus as opposed to the Concept of the Depreciation of Sterling This situation is simply described by saying that the pound sterling depreciated 'in terms of gold,' or still more simply that it 'depreciated.' In the use of these terms, which might be applied equally to the currencies of Peru, Spain, or Aus- tralia, there is a danger to clear thinking, not because they do not accurately describe the surface facts, but because they carry certain implications. To say that sterling has depre- ciated in terms of gold implies that nothing very serious has happened to gold as an international monetary standard, and that the international gold standard system continues to operate as before, with only the loss of one of its members. -

CURRENCY BOARD FINANCIAL STATEMENTS Currency Board Working Paper

SAE./No.22/December 2014 Studies in Applied Economics CURRENCY BOARD FINANCIAL STATEMENTS Currency Board Working Paper Nicholas Krus and Kurt Schuler Johns Hopkins Institute for Applied Economics, Global Health, and Study of Business Enterprise & Center for Financial Stability Currency Board Financial Statements First version, December 2014 By Nicholas Krus and Kurt Schuler Paper and accompanying spreadsheets copyright 2014 by Nicholas Krus and Kurt Schuler. All rights reserved. Spreadsheets previously issued by other researchers are used by permission. About the series The Studies in Applied Economics of the Institute for Applied Economics, Global Health and the Study of Business Enterprise are under the general direction of Professor Steve H. Hanke, co-director of the Institute ([email protected]). This study is one in a series on currency boards for the Institute’s Currency Board Project. The series will fill gaps in the history, statistics, and scholarship of currency boards. This study is issued jointly with the Center for Financial Stability. The main summary data series will eventually be available in the Center’s Historical Financial Statistics data set. About the authors Nicholas Krus ([email protected]) is an Associate Analyst at Warner Music Group in New York. He has a bachelor’s degree in economics from The Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore, where he also worked as a research assistant at the Institute for Applied Economics and the Study of Business Enterprise and did most of his research for this paper. Kurt Schuler ([email protected]) is Senior Fellow in Financial History at the Center for Financial Stability in New York. -

My Recollections of the Introduction of Botswana's Pula Currency on 23

A Special Issue on Botswana Notes and Records’ Golden Jubilee Volume in Honour of Sir Ketumile Masire My Recollections of the Introduction of Botswana’s Pula Currency on 23 August 1976 Derek Hudson∗ In 1975, the government of Botswana set up a Monetary Preparatory Commission to oversee the introduction of Botswana’s first ever currency. This was under the overall guidance of Quett Ketumile Masire (later Sir Ketumile Masire), the then Minister of Finance and Development Planning (MFDP). He in turn, was strongly supported by President Sir Seretse Khama. Since 1961, Botswana had used the South African rand as its currency, and before that the South African pound and the Cape Colony pound. In 1910 the Union of South Africa was established and it began to use the South African pound, which, like the Cape Colony pound, was on par with the British pound. Until 30 September 1966 Botswana was under British colonial control and called Bechuanaland Protectorate. In 1961, South Africa became left the Commonwealth to become a republic and replaced the pound with the rand, which automatically become the legal tender of Botswana. This was after it had been decided in principle that Botswana would have its own currency. This would allow Botswana, for the first time, to determine the value of its own currency and to set its own interest rates, instead of automatically copying whatever South Africa did. For the first time ever, Botswana could choose the designs for its own notes and coins. It would also allow Botswana to decide for itself how many, if any, of South Africa’s complex regime of exchange control regulations should be retained. -

South Africa's Experience of Regional Currency Areas and the Use Of

South Africa’s experience of regional currency areas and the use of foreign currencies Lambertus van Zyl1 1. Introduction This paper focuses almost exclusively on South Africa’s current and potential experience of regional currency areas in the Common Monetary Area (CMA) and the Southern African Development Community (SADC). There is no evidence that foreign currency is being used in any meaningful way inside South Africa. Thus no official and very little unofficial dollarisation has taken place in South Africa notwithstanding significant exchange control liberalisation in recent years. On the contrary, the South African rand is used extensively as legal tender in other countries comprising the CMA while anecdotal evidence points to the rand being accepted as payment in some other countries in SADC. However, no statistics are available to corroborate the extent to which the rand is used outside the CMA. There are various regional integration initiatives involving the southern African region, each with its own programme of action. South Africa is not directly involved in all these initiatives. South Africa, for instance, is not a member of the Common Market for Eastern and Southern Africa or the Cross-border Initiative. However, as their objectives are focused on regional economic integration, they overlap with the objectives of regional initiatives to which South Africa actively subscribes, such as the recent decision by African heads of state on the creation of an African Union and a common monetary bloc as well as the Southern African Customs Union. Of most relevance to this paper, however, is South Africa’s membership of the CMA with Lesotho, Swaziland and Namibia. -

Metadata on the Exchange Rate Statistics

Metadata on the Exchange rate statistics Last updated 26 February 2021 Afghanistan Capital Kabul Central bank Da Afghanistan Bank Central bank's website http://www.centralbank.gov.af/ Currency Afghani ISO currency code AFN Subunits 100 puls Currency circulation Afghanistan Legacy currency Afghani Legacy currency's ISO currency AFA code Conversion rate 1,000 afghani (old) = 1 afghani (new); with effect from 7 October 2002 Currency history 7 October 2002: Introduction of the new afghani (AFN); conversion rate: 1,000 afghani (old) = 1 afghani (new) IMF membership Since 14 July 1955 Exchange rate arrangement 22 March 1963 - 1973: Pegged to the US dollar according to the IMF 1973 - 1981: Independently floating classification (as of end-April 1981 - 31 December 2001: Pegged to the US dollar 2019) 1 January 2002 - 29 April 2008: Managed floating with no predetermined path for the exchange rate 30 April 2008 - 5 September 2010: Floating (market-determined with more frequent modes of intervention) 6 September 2010 - 31 March 2011: Stabilised arrangement (exchange rate within a narrow band without any political obligation) 1 April 2011 - 4 April 2017: Floating (market-determined with more frequent modes of intervention) 5 April 2017 - 3 May 2018: Crawl-like arrangement (moving central rate with an annual minimum rate of change) Since 4 May 2018: Other managed arrangement Time series BBEX3.A.AFN.EUR.CA.AA.A04 BBEX3.A.AFN.EUR.CA.AB.A04 BBEX3.A.AFN.EUR.CA.AC.A04 BBEX3.A.AFN.USD.CA.AA.A04 BBEX3.A.AFN.USD.CA.AB.A04 BBEX3.A.AFN.USD.CA.AC.A04 BBEX3.M.AFN.EUR.CA.AA.A01 -

Propose Reserve Currency Table – for PDF Copy

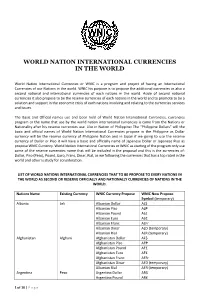

WORLD NATION INTERNATIONAL CURRENCIES IN THE WORLD World Nation International Currencies or WNIC is a program and project of having an International Currencies of our Nations in the world. WNIC his purpose is to propose the additional currencies as also a second national and international currencies of each nations in the world. Aside of second national currencies it also propose to be the reserve currencies of each nations in the world and to promote to be a solution and support in the economic crisis of each nations involving and relating to the currencies services and issues. The Basic and Official names use and been hold of World Nation International Currencies, currencies program or the name that use by the world nation international currencies is came from the Nations or Nationality after his reserve currencies use. Like in Nation of Philippine: The “Philippine Dollars” will the basic and official names of World Nation International Currencies propose in the Philippine as Dollar currency will be the reserve currency of Philippine Nation and in Japan if we going to use the reserve currency of Dollar or Piso it will have a basic and officially name of Japanese Dollar or Japanese Piso as propose WNIC Currency. World Nation International Currencies or WNIC as starting of the program only use some of the reserve currencies name that will be included in the proposal and this is the currencies of: Dollar, Piso (Peso), Pound, Euro, Franc, Dinar, Rial, as we following the currencies that has a top rated in the world and other is study for consideration. -

Diamantjubileum Van Desimalisasie: 60 Jaar Van Suid-Afrikaanse Rand En Sent1 Diamond Jubilee of Decimalisation: 60 Years of South African Rand and Cent

658 Diamantjubileum van desimalisasie: 60 jaar van Suid-Afrikaanse rand en sent1 Diamond jubilee of decimalisation: 60 years of South African rand and cent JANNIE ROSSOUW Wits Besigheidskool Universiteit van die Witwatersrand Johannesburg E-pos: [email protected] Jannie Rossouw JANNIE ROSSOUW is tussentydse Hoof en Direk- JANNIE ROSSOUW is interim Head and Director teur van Wits Besigheidskool aan die Universiteit of Wits Business School. Previously he worked van die Witwatersrand. Hy was voorheen at the South African Reserve Bank. He has werksaam by die Suid-Afrikaanse Reserwebank. published numerous academic papers in accre- Sy vernaamste navorsingsvelde sluit in Suid- dited journals in South Africa and abroad, and Afrika se naderende fiskale afgrond, geloof addressed local and international conferences on waardige en akkurate inflasiesyfers en konver his research interests. His research focuses on gensie en armoedebekamping in die SAOG- inflation perceptions, South Africa’s looming streek. Hy het etlike akademiese artikels in vak- fiscal cliff and poverty eradication and conver wetenskaplike tydskrifte gepubliseer en spreek gence in the SADC region. gereeld plaaslike en internasionale konferensies toe. ABSTRACT Diamond jubilee of decimalisation: 60 years of South African rand and cent The Union of South Africa, the precursor to the Republic of South Africa, introduced a decimal coinage system, comprising rand and cents, on 14 February 1961. The rand and cents replaced the imperial system of pounds, shillings and pennies (£/s/d). The decimalisation of 1961 is often associated with the establishment of the Republic of South Africa on 31 May 1961, but these were indeed two different processes that happened in the same year. -

Susan Mercer's Money Talk 10 Years to Retirement?

Susan Mercer’s Money Talk Quarter 1 / 2016 10 years to retirement? Follow these 5 tips and make it easy The actions you take in the final decade before you quit working are crucial to getting the next phase off to a smooth start. Here are 5 things you must do. After 30-plus years of working and saving, make up 50% to 60% of your allocation, you can finally see retirement on the with the rest in a stable portfolio. The horizon. But it’s not time to coast just yet. caveat: those within 10% of their ultimate savings goal can choose to dial back to 1. See if you’re saving enough. If you 40%. haven’t recently, take stock of where you are and where you need to be. For exam- 4. Be mortgage wise. Of course you don’t ple, to replace 70% of your earnings by want to carry credit card debt into retire- age 65, you’ll need to accumulate 12 ment, but what about the mortgage? The times your pay at 65. But even if you’re old advice was to settle it before you left playing catch-up, you can still make it to work, but in today’s low-rate environ- the finish line with what you need. Your ment, maybe not. Assuming that your choice: Seriously power-save, or work a rate is less than 9.75% and that you’ll be bit longer while saving less. Say you have able to afford the payments from guaran- five times your income; you could save teed-income sources in retirement—or if 33% a year for the next 10 years, or delay you’re planning to move—there’s no retirement 24 months while banking rush. -

The Big Reset

REVISED s EDITION Willem s Middelkoop s TWarh on Golde and the Financial Endgame BIGs s RsE$EAUPTs The Big Reset The Big Reset War on Gold and the Financial Endgame ‘Revised and substantially enlarged edition’ Willem Middelkoop AUP Cover design: Studio Ron van Roon, Amsterdam Photo author: Corbino Lay-out: Crius Group, Hulshout Amsterdam University Press English-language titles are distributed in the US and Canada by the University of Chicago Press. isbn 978 94 6298 027 3 e-isbn 978 90 4852 950 6 (pdf) e-isbn 978 90 4852 951 3 (ePub) nur 781 © Willem Middelkoop / Amsterdam University Press B.V., Amsterdam 2016 All rights reserved. Without limiting the rights under copyright reserved above, no part of this book may be reproduced, stored in or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise) without the written permission of both the copyright owner and the author of the book. To Moos and Misha In the absence of the gold standard, there is no way to protect savings from confiscation through inflation. There is no safe store of value. If there were, the government would have to make its holding illegal, as was done in the case of gold. If everyone decided, for example, to convert all his bank deposits to silver or copper or any other good, and thereafter declined to accept checks as payment for goods, bank deposits would lose their purchasing power and government-created bank credit would be worthless as a claim on goods. -

Union of South Africa ••••••• 27 Unroll of SOUTH Afaica Basic Statistics

1$ * No. E 12la RESTRICTED ~ .. J, ThiS report is restricted to use within the Bank. I Public Disclosure Authorized INTERNATIONAL BANK FOR RECONSTRUCTION AND DEVELOPMENT Public Disclosure Authorized REPORT ON THE ECONOMY OF SOUTH AFRICA December 13, 1950 Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized Economic Department Prepared by: J. H. Collier CONTENTS PAGE Basic Statistics Summary and Conclusions ••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••• i I. The structure of the South African Bconomy •••••..••••••••••• 1 1) Geographical Background •••••••••••••••••••••••••••• 1 2) Population ........•. ,. ....•....•.......... " . 1 J ) ~Ia-'viorlal Income •••...••• .,.............................. 2 II. The Postwar Position of the South African Economy ••••••••••• 4 1) Liquid Position at the End of the i:!ar.............. 4 2) The Investment Boom ................................. 5 J) Government Investment a~d Budgetary Policy••••••••• 7 4) Currency and Banking Policy ••••••••••••••••••••.••• 9 III. The South African Balance of Payments.~ ••••••••••••••••••••• 10 1) The Traditional Sources of Foreign Exchange •••••••• 10 2} The Balance of Payments Effect of the Postwar Boom. 16 3.) The Hard Currency Position ••••••••••••••••••••••••• 18 4) The Need for Non-Sterling Capital •••••••••••••••••• 20 IV. The Future Ureditworthiness of South Africao ••• ~ ••••••••••• $ 21 1) The Importance of the Over-all Balan~e of Payments Positiono •••••••.•••••••••••••• 21 2) The Prospects for Over-all Current Account Balance. 21 3) The Pattern of Development and its Effect on the Dalance of Payments ••••••••••••••••••••• 22 4) The Risk Elements in a Bank Loan •••••••••••.••••••• 24 v. The External Debt ~ecord of the Union of South Africa ••••••• 27 UNrOll OF SOUTH AFaICA Basic Statistics Total Area 472,000 sq. miles :'opulation 12.1 million l'Iational Income (1948/49) S.A.b 831.7 million Of which: Agriculture 124.2 II Manufacturing, private 195.4 II ulining 93.0 11 Q.urrency Unit South African Pound Exchange rate S.A.b 1 =U.S.~2.80 Prices Home goods 1937 =100 sept.