Transcendence and Immanence Théodore Koehler

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Divine Liturgy

5. THE HOLY ANAPHORA eacon: Let us stand aright; let us stand with fear; Dlet us attend, that we may offer the Holy Anapho - ra in peace . Choir: A mercy of peace, a sacrifice of praise . Let us stand with fear With the Holy Anaphora, which now begins, we reach the most sacred moment of the Divine Liturgy. That is why the deacon calls on us to pay attention to how we stand, both in soul and body: Let us stand aright; let us stand with fear . In St John Chrysostom’s time, this exclamation took a slightly different form: ‘Stand up; let us stand aright.’ 1 St John interprets the meaning of this exhortation as follows: We should ‘elevate our base and earth-bound thoughts and rid ourselves of the spiritual paralysis induced by the cares of this life, so that we can present our souls upstanding before God … Think in whose presence you are, and with whom you will call upon God — with the Cherubim … So no one should take part in these sacred and mystical hymns indolently … On the contrary, one should expel all things earthly from one’s mind and trans - port oneself totally to heaven, and then offer the all-holy hymn to the God of glory and majesty as if standing before the very throne of glory and flying with the Seraphim. That is why the deacon 1 The corresponding exclamation in the Apostolic Constitutions reads: ‘Stand up; let us be standing with fear and trembling to make our offering to the Lord’ ( Constitutions , 8.12, PG 1.1092A). -

Aspects of St Anna's Cult in Byzantium

ASPECTS OF ST ANNA’S CULT IN BYZANTIUM by EIRINI PANOU A thesis submitted to The University of Birmingham for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Centre for Byzantine, Ottoman and Modern Greek Studies Institute of Archaeology and Antiquity College of Arts and Law The University of Birmingham January 2011 Acknowledgments It is said that a PhD is a lonely work. However, this thesis, like any other one, would not have become reality without the contribution of a number of individuals and institutions. First of all of my academical mother, Leslie Brubaker, whose constant support, guidance and encouragement accompanied me through all the years of research. Of the National Scholarship Foundation of Greece ( I.K.Y.) with its financial help for the greatest part of my postgraduate studies. Of my father George, my mother Angeliki and my bother Nick for their psychological and financial support, and of my friends in Greece (Lily Athanatou, Maria Sourlatzi, Kanela Oikonomaki, Maria Lemoni) for being by my side in all my years of absence. Special thanks should also be addressed to Mary Cunningham for her comments on an early draft of this thesis and for providing me with unpublished material of her work. I would like also to express my gratitude to Marka Tomic Djuric who allowed me to use unpublished photographic material from her doctoral thesis. Special thanks should also be addressed to Kanela Oikonomaki whose expertise in Medieval Greek smoothened the translation of a number of texts, my brother Nick Panou for polishing my English, and to my colleagues (Polyvios Konis, Frouke Schrijver and Vera Andriopoulou) and my friends in Birmingham (especially Jane Myhre Trejo and Ola Pawlik) for the wonderful time we have had all these years. -

“Make This the Place Where Your Glory Dwells”: Origins

“MAKE THIS THE PLACE WHERE YOUR GLORY DWELLS”: ORIGINS AND EVOLUTION OF THE BYZANTINE RITE FOR THE CONSECRATION OF A CHURCH A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate School of the University of Notre Dame in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy by Vitalijs Permjakovs ____________________________ Maxwell E. Johnson, Director Graduate Program in Theology Notre Dame, Indiana April 2012 © Copyright 2012 Vitalijs Permjakovs All rights reserved “MAKE THIS THE PLACE WHERE YOUR GLORY DWELLS”: ORIGINS AND EVOLUTION OF THE BYZANTINE RITE FOR THE CONSECRATION OF A CHURCH Abstract by Vitalijs Permjakovs The Byzantine ritual for dedication of churches, as it appears in its earliest complete text, the eighth-century euchologion Barberini gr. 336, as well as in the textus receptus of the rite, represents a unique collection of scriptural and euchological texts, together with the ritual actions, intended to set aside the physical space of a public building for liturgical use. The Byzantine rite, in its shape already largely present in Barberini gr. 336, actually comprises three major liturgical elements: 1) consecration of the altar; 2) consecration of the church building; 3) deposition of relics. Our earliest Byzantine liturgical text clearly conceives of the consecration of the altar and the deposition of the relics/“renovation” (encaenia) as two distinct rites, not merely elements of a single ritual. This feature of the Barberini text raises an important question, namely, which of these major elements did in fact constitute the act of dedicating/ consecrating the church, and what role did the deposition of relics have in the ceremonies of dedication in the early period of Byzantine liturgical history, considering that the deposition of relics Vitalijs Permjakovs became a mandatory element of the dedication rite only after the provisions to that effect were made at the Second council of Nicaea in 787 CE. -

Gaining the Attention of the Mind

Gaining the Attention of the Mind One of the major challenges in our prayer life is the wandering of our mind. Here is what some of the Holy People say about this. We begin with one of the Syriac Fathers, Evagrius: "Be careful lest your mind wander during your time of prayer, thinking about empty things. In that case you will stir the Judge to anger, rather than to good will, seeing that he has been insulted by you. Should you be afraid in the presence of ordinary judges but show contempt in the presence of God? How can a person who is not aware of where his is standing and what he is saying imagine of himself that he is offering up prayer?..." This is a powerful admonition. How can one expect to be in relationship with another person when your mind is not focused on the conversation with them. And how much more important this is with God. What an insult it is to Him. This is surely taking the Lord's name in vane when we let our minds wander while calling out to him for help and forgiveness. He continues with a powerful punch: "Arouse yourself, wretch; your Lord is speaking with you. Do not wander off. His elect angels surround you, do not be dismayed; the ranks of the demons stand facing you, so do not grow lax." Wretch? These are very strong terms he is using. The dictionary says this is "a despicable or contemptible person." He says rather directly "Do not wander off." This tendency we must fight with all our ability. -

The Life and Mission of St. Paisius Velichkovsky. 1722–1794. an Early Mod- Ern Master of the Orthodox Spiritual Life

The Life and Mission of St. Paisius Velichkovsky. 1722–1794. An Early Mod- ern Master of the Orthodox Spiritual Life John A. MCGuckin Many people today have become familiar with the figure of the Russian Pilgrim. The book, The Way of a Pilgrim purports to have been written as the 157 autobiographical record of a poor and barely educated Russian peasant of the 19th century. Treading his way across the Steppes, enduring countless hardships and adventures as he persevered, gripped only with the reading of his beloved book of the spiritual writers of the Early Church, he directed all his mental energies around the countless recitation: “Lord Jesus Christ, Son of God, have mercy on me a sinner.” This famous story is designed to advocate how the prayer of the heart can happen if one wills it: a mystical transitioning from prayer on the lips, to prayer in the mind, to prayer of the heart: namely, prayer in the deepest levels of the human spirit’s personal communion with the Risen Christ. The work in its English translation had a remarkable resonance in 20th century Europe and America; so much so, that nowadays if one asks about the spirituality of the pilgrim, most would think first of Russia and its mystical tra- dition of the Jesus Prayer, and perhaps hardly at all of the Puritans! The book’s popularity was helped along, doubtless, by its starred appearance in J.D. Salin- ger’s Franny and Zooey in 1961. It first came out in 1884 in a Russian version entitled: “Candid Tales of a Pilgrim to His Spiritual Father.” In all likelihood it emanated originally from the St. -

This Thesis Has Been Submitted in Fulfilment of the Requirements for a Postgraduate Degree (E.G

This thesis has been submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for a postgraduate degree (e.g. PhD, MPhil, DClinPsychol) at the University of Edinburgh. Please note the following terms and conditions of use: This work is protected by copyright and other intellectual property rights, which are retained by the thesis author, unless otherwise stated. A copy can be downloaded for personal non-commercial research or study, without prior permission or charge. This thesis cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the author. The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the author. When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given. Meaning and Normativity of Jerusalem Council’s Prohibitions in Relation to Textual Variants of Acts 15:20.29 and Acts 21:25. An Analysis and Comparison of Early Interpretations (2nd-5th Century) by Wojciech Paweł Rybka A dissertation submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the University of Edinburgh 2017 2 Declaration I hereby confirm that the work contained within has been composed by me and that no part of it has been submitted for any other degree or professional qualification. Signed: Wojciech Paweł Rybka 3 Abstract The thesis collects and analyses the very first (2nd-5th century) clear quotations, references and interpretations of Acts 15:20.29 and Acts 21:25. It consists of three parts: Part I, which is introductory in nature, presents and comments upon the textual variants of these biblical verses. -

A Study of the Antecedents of in Persona Christi Theology in Ancient Christian Tradition

The Representation of Christ by the Priest: A Study of the Antecedents of in persona Christi Theology in Ancient Christian Tradition G. Pierre Ingram, CC Thesis submitted to the Faculty of Theology, Saint Paul University, in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor in Theology Ottawa, Canada April 2012 © G. Pierre Ingram, Ottawa, Canada, 2012 To my parents: Donald George Ingram († 1978) and Pierrette Jeanne Ingram († 2005) Contents Abbreviations ...................................... .......................... vi INTRODUCTION ....................................... .............................1 1 Contemporary Context ............................. ............................1 2 Statement of the Problem ......................... ..............................2 3 Objectives....................................... ............................5 4 Research Hypothesis .............................. ............................5 5 Methodological Approach .......................... ............................6 6 Structure of the Dissertation . .................................7 CHAPTER 1 THE USE OF "IN PERSONA CHRISTI" IN CATHOLIC TEACHING AND THEOLOGY . 9 1 Representation of Christ as a Feature of the Theology of Ministry in General . 9 2 The Use of the Phrase in persona Christi in Roman Catholic Theology . 11 2.1 Pius XI ........................................ ....................13 2.2 Pius XII ....................................... ....................14 2.3 The Second Vatican Council ..................... ......................21 -

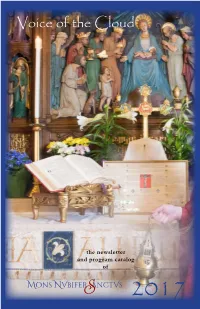

Voice of the Cloud

Voice of the Cloud the newsletter and program catalog of Mons NVbiferS anctVs 2017 In This Issue: 1. Letter From Fr. James 3. News & Happenings 4. Essay: Contemplative Prayer: Knowing God in the Biblical Sense 8. Signs of the Saints: Hesychius of Jerusalem, Writings from the Philokalia On the Prayer of the Heart 9. Upcoming Programs and Retreats Theoria, Leituorgeia, Diakonia, Koinonia Contemplation, Liturgy, Service, Communion Recapturing the vision of God. ostering full-contact discipleship in a fragmented world, Mons Nubifer Sanctus is a place set apart for the meticulous studyF and practice of contemplative Christianity. We emphasize life-long, face-to-face spiritual companionships and mentorships, and a life daily inspired by the vision of God that reaches beyond a Sunday to Sunday obligation. Grounded in the fullness of the ancient faith, our programs are aimed at the realization of truly Christian character, the knowledge of God, and wakefulness to divine love. e encourage Authenticity and Maturity for the development Wof Virtue and Clarity. e seek Reconciliation and Renewal for the realization of WFlourishing and Fullness, Consummated in the love of God. Mons Nubifer Sanctus 55 Lake Delaware Drive Delhi, NY 13753 607-832-4401 [email protected] www.MonsNubifer.org Dear Friends of Mons Nubifer Sanctus, Greetings in the peace of Jesus. For many months, I have been writing, blogging and speaking about some of the key challenges facing us as a nation. I have been clear that it is the calling of Christians to rise above what I perceive as an emotionally regressive atmosphere, characterized by reactivity, polarization, a herding mentality and political fundamentalism. -

Jerusalem II: Jerusalem in Roman-Byzantine Times

Civitatum Orbis MEditerranei Studia Edited by Reinhard Feldmeier (Göttingen), Friedrich V. Reiterer (Salzburg), Karin Schöpflin (Göttingen), Ilinca Tanaseanu-Döbler (Göttingen) and Kristin De Troyer (Salzburg) 5 Jerusalem II: Jerusalem in Roman-Byzantine Times edited by Katharina Heyden and Maria Lissek with the assistance of Astrid Kaufmann Mohr Siebeck Katharina Heyden, born 1977, received her academic education in Berlin, Jerusalem, Rom, Jena and Göttingen. Since 2014, she holds the chair for Ancient History of Christianity and Interreligious Encounters at the University of Bern. She presides the “Team Interreligious Studies” and is the Director of the Interfaculty Research Cooperation “Religious Conflicts and Coping Strategies”. orcid.org/0000-0001-5478-1613 Maria Lissek, born 1986, studied theology in Bamberg, Marburg, Jerusalem and Tübingen, was academic assistant in Jerusalem and research fellow in Oxford. Since 2020, she is postdoc at the Institute of Historical Theology at the University of Bern. ISBN 978-3-16-158303-2 / eISBN 978-3-16-159809-8 DOI 10.1628/978-3-16-159809-8 ISSN 2196-9264 / eISSN 2569-3891 (Civitatum Orbis MEditerranei Studia) The Deutsche Nationalbibliothek lists this publication in the Deutsche Nationalbiblio graphie; detailed bibliographic data are available at http://dnb.dnb.de. © 2021 Mohr Siebeck Tübingen, Germany. www.mohrsiebeck.com This book may not be reproduced, in whole or in part, in any form (beyond that permitted by copyright law) without the publisher’s written permission. This applies particularly to repro- ductions, translations and storage and processing in electronic systems. The book was typeset by Martin Fischer in Tübingen using Times typeface, printed on non- aging paper by Gulde Druck in Tübingen, and bound by Buchbinderei Spinner in Ottersweier. -

Patristic Studies in the Twenty-First Century: an International Conference to Mark the 50Th Anniversary of AIEP/IAPS Preliminary Conference Programme

Patristic Studies in the Twenty-first Century: An International Conference to Mark the 50th Anniversary of AIEP/IAPS Preliminary Conference Programme (Abstracts listed alphabetically after p. 9) Tuesday, June 25 9:00 Opening ceremonies 9:30 Adolf Martin Ritter, Ruprecht-Karls Universität, “The Origins of AIEP” 10:00 Break 10:30 Overview of patristic studies (1) Europe (Lorenzo Perrone, Università di Bologna) North America (Dennis Trout, University of Missouri) South America (Francisco García Bazán, CONICET) 12:30 Lunch 14:00 Angelo Di Berardino, Institutum Patristicum Augustinianum, “The Development of AIEP” 14:30 Overview of patristic studies (2) Asia (Satoshi Toda, Hitotsubashi University) Australia (Bronwen Neil, Australian Catholic University) Africa (Michel Libambu, Université catholique du Congo) 16:30 Break 17:30 Susan Ashbrook Harvey, Brown University, “Patristic Worlds” 18:30 Reception and banquet 1 Wednesday, June 26 Theme 1: Patristics and the confluence of Jewish, Christian and Muslim cultures: what does patristics mean for scholars in communities with a combination of Jewish, Christian, and Muslim identities? 9:00 Plenary Lecture: Aryeh Kofsky, Haifa University, “Studying Patristics as an Outsider: Does it Make a Difference?” 10:00 Break 10:30 Session 1 Menahem Kister, Hebrew University of Jerusalem, “Aphrahat Concerning Christ’s Divinity and Sonship: Jewish Opponents and Christian Sources” Reuven Kiperwasser and Serge Ruzer, Hebrew University of Jerusalem, “Syriac Christians and Babylonian Jewry: Narratives and Identity-Shaping -

Biographical Sketches & Short Descriptions of Select Anonymous

Biographical Sketches & Short Descriptions of Select Anonymous Works This listing is cumulative, including all the authors and works cited in this series to date. Abraham of Nathpar (fl. sixth-seventh to Origen. However, trinitarian terminology, century). Monk of the Eastern Church who coupled with references to Methodius and allu- flourished during the monastic revival of the sions to the fourth-century Constantinian era sixth to seventh century. Among his works is bring this attribution into question. a treatise on prayer and silence that speaks of Adamnan (c. 624-704). Abbot of Iona, Ireland, the importance of prayer becoming embodied and author of the life of St. Columba. He was through action in the one who prays. His work influential in the process of assimilating the has also been associated with John of Apamea Celtic church into Roman liturgy and church or Philoxenus of Mabbug. order. He also wrote On the Holy Sites, which Acacius of Beroea (c. 340-c. 436). Syrian monk influenced Bede. known for his ascetic life. He became bishop Alexander of Alexandria (fl. 312-328). Bishop of Beroea in 378, participatedSAMPLE—DO in the council of of Alexandria NOT and predecessor COPY of Athanasius, Constantinople in 381, and played an important on whom he exerted considerable theological role in mediating between Cyril of Alexandria influence during the rise of Arianism. Alexander and John of Antioch; however, he did not take excommunicated Arius, whom he had appointed part in the clash between Cyril and Nestorius. to the parish of Baucalis, in 319. His teach- Acacius of Caesarea (d. -

Liturgy 11:20 - 13:00 Thursday, 22Nd August, 2019 Room 9 Presentation Type Short Communications

Liturgy 11:20 - 13:00 Thursday, 22nd August, 2019 Room 9 Presentation type Short Communications 843 Beyond Diabasis Alone: Philo’s Alternative Liturgical Theology of Pascha as Received in Early Christian Computus Maria Theotokos Adams, SSVM Catholic University of America, Washington, DC, USA Abstract Drawing on Philo of Alexandria, Origen famously promoted a corrective etymology for pascha as meaning “crossing” (diabasis) from the transliterated Hebrew word fasek, as opposed to “suffering” (paschein) from the homophone Greek verb. Many early Christian authors readily accepted and shared this view including Eusebius of Caesarea, Gregory Nazianzus, Jerome, Maximus of Turin, and Augustine. Philo seems to interpret feast of pascha as a memorial emphasizing the crossing of the Red Sea (diabasis) over and above the slaughter of the lamb and the miracle of its protection for the Hebrew families on 14 Nisan. However, a more comprehensive reading of Philo’s etymologies and references to pascha reveals that he equally used diabateria as a second term to explain the meaning of the feast. His choice of this expression meaning “the sacrifice before a crossing” suggests a daring Classical allusion to Spartan practice which recasts the two poles of the Exodus events – sacrifice and passage – into a new harmonic whole. Anatolius of Laodicea and Eusebius of Caesarea demonstrate how the alternative etymology diabateria was preferred within the context of the technical and theological challenges of paschal computus. Like Origen they invoke the antiquity and authority of the Jewish scholars to defend their methods, but they depart from Origen in his nearly exclusive use of diabasis in favor of a balanced solution between sacrifice on 14 Nisan (diabateria) and victorious passage on “the third day” (diabasis).