Mid-Term Performance Evaluation of the Justice for All Program

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

List of Upazilas of Bangladesh

List Of Upazilas of Bangladesh : Division District Upazila Rajshahi Division Joypurhat District Akkelpur Upazila Rajshahi Division Joypurhat District Joypurhat Sadar Upazila Rajshahi Division Joypurhat District Kalai Upazila Rajshahi Division Joypurhat District Khetlal Upazila Rajshahi Division Joypurhat District Panchbibi Upazila Rajshahi Division Bogra District Adamdighi Upazila Rajshahi Division Bogra District Bogra Sadar Upazila Rajshahi Division Bogra District Dhunat Upazila Rajshahi Division Bogra District Dhupchanchia Upazila Rajshahi Division Bogra District Gabtali Upazila Rajshahi Division Bogra District Kahaloo Upazila Rajshahi Division Bogra District Nandigram Upazila Rajshahi Division Bogra District Sariakandi Upazila Rajshahi Division Bogra District Shajahanpur Upazila Rajshahi Division Bogra District Sherpur Upazila Rajshahi Division Bogra District Shibganj Upazila Rajshahi Division Bogra District Sonatola Upazila Rajshahi Division Naogaon District Atrai Upazila Rajshahi Division Naogaon District Badalgachhi Upazila Rajshahi Division Naogaon District Manda Upazila Rajshahi Division Naogaon District Dhamoirhat Upazila Rajshahi Division Naogaon District Mohadevpur Upazila Rajshahi Division Naogaon District Naogaon Sadar Upazila Rajshahi Division Naogaon District Niamatpur Upazila Rajshahi Division Naogaon District Patnitala Upazila Rajshahi Division Naogaon District Porsha Upazila Rajshahi Division Naogaon District Raninagar Upazila Rajshahi Division Naogaon District Sapahar Upazila Rajshahi Division Natore District Bagatipara -

Technical Assistance Layout with Instructions

Environmental Monitoring Report Project Number: 40515-013 Semi-annual Report July to December 2017 2696-BAN(SF): Sustainable Rural Infrastructure Improvement Project Prepared by Local Government Engineering Department (LGED) for the People’s Republic of Bangladesh and the Asian Development Bank. This environmental monitoring report is a document of the borrower. The views expressed herein do not necessarily represent those of ADB's Board of Directors, Management, or staff, and may be preliminary in nature. In preparing any country program or strategy, financing any project, or by making any designation of or reference to a particular territory or geographic area in this document, the Asian Development Bank does not intend to make any judgments as to the legal or other status of any territory or area. Semi-Annual Environmental Report Sustainable Rural Infrastructure Improvement Project (SRIIP) 31 December 2017 Local Government Engineering Department (LGED) Mott MacDonald Plot 77, Level 6 Block-M Road 11 Banani Dhaka Dhaka 1213 Bangladesh T +880 (2) 986 1194 F +880 (2) 986 0319 mottmac.com/international- development Local Government Engineering Department (LGED) Semi-Annual Environmental RDEC Bhaban (Level-6) 377583 1 0 Agargaon, Sher-e-Bangla Report C:\Users \RAN58195\AppData\Local\Microsoft\Windows\Temporary Internet nagar Dhaka-1207, Files\Content.Outlook\8QF6OYF8\377583-Semi-Annual Environmental Report2017.docx Mott MacDonald Bangladesh Sustainable Rural Infrastructure Improvement Project (SRIIP) 31 December 2017 Euroconsult Mott MacDonald bv is a member of the Mott MacDonald Group. Registered in The Netherlands no. Local Government Engineering Department (LGED) 09038921 Mott MacDonald | Semi-Annual Environmental Report Sustainable Rural Infrastructure Improvement Project (SRIIP) Issue and Revision Record Revision Date Originator Checker Approver Description A 31 Mehedi Hasan Md. -

M.Sc Thesis, for His Patience, Motivation, Enthusiasm, and Immense Knowledge

ASSESSMENT OF GROUNDWATER RESOURCES IN BOGRA DISTRICT USING GROUNDWATER MODEL MUHAMMAD ABDULLAH DEPARTMENT OF CIVIL ENGINEERING BANGLADESH UNIVERSITY OF ENGINEERING AND TECHNOLOGY OCTOBER, 2014 Assessment of Groundwater Resources in Bogra District using Groundwater Model by Muhammad Abdullah Student No. 0409042201 (F) In Partial fulfillment of the requirement for the degree of MASTER OF SCIENCE IN CIVIL ENGINEERING Department of Civil Engineering BANGLADESH UNIVERSITY OF ENGINEERING AND TECHNOLOGY, DHAKA October, 2014 The thesis titled Assessment of Groundwater Resources in Bogra District using Groundwater Model submitted by Muhammad Abdullah, Student No: 0409042201 (F), Session: April, 2009 has been accepted as satisfactory in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science in Civil Engineering (Geotechnical) on October 2014. BOARD OF EXAMINERS Dr. Syed Fakhrul Ameen Professor Department of Civil Engineering Chairman BUET, Dhaka (Supervisor) Dr. Mahbuboor Rahman Choudhury Member Assistant Professor (Co-Supervisor) Department of Civil Engineering BUET, Dhaka Member Dr. Tanvir Ahmed Assistant Professor Department of Civil Engineering BUET, Dhaka Member Dr. A.M.M. Taufiqul Anwar (Ex - officio) Professor and Head Department of Civil Engineering BUET, Dhaka Member Dr. A.F.M Afzal Hossain (External) Deputy Executive Director (P&D) Institute of Water Modelling (IWM) H-496, R-32, New DOHS, Mohakhali, Dhaka. ii CANDIDATE’S DECLARATION It is hereby declared that this thesis or any part of it has not been submitted elsewhere for the award of any degree or diploma. Muhammad Abdullah iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENT Foremost, I would like to express my sincere gratitude to my supervisor Dr. Syed Fakhrul Ameen, Professor, Department of Civil Engineering, BUET for his special support of my M.Sc thesis, for his patience, motivation, enthusiasm, and immense knowledge. -

Inventory of LGED Road Network, March 2005, Bangladesh

BASIC INFORMATION OF ROAD DIVISION : RAJSHAHI DISTRICT : BOGRA ROAD ROAD NAME CREST TOTAL SURFACE TYPE-WISE BREAKE-UP (Km) STRUCTURE EXISTING GAP CODE WIDTH LENGTH (m) (Km) EARTHEN FLEXIBLE BRICK RIGID NUMBER SPAN NUMBER SPAN PAVEMENT PAVEMENT PAVEMEN (m) (m) (BC) (WBM/HBB/ T BFS) (CC/RCC) 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 UPAZILA : GABTALI ROAD TYPE : UPAZILA ROAD 110402004 Bogra - Tarnirhat G.C.C. Road 5.66 11.000.00 11.00 0.00 0.00 5 19.00 0 0.00 110402005 Tarnirhat G.C - Chandanbaisa G.C.C. Road(Gabtali 5.66 2.500.70 1.80 0.00 0.00 1 80.00 0 0.00 Part). 110402006 Naruamala G.C- Sonatala G.C.C.Road(Gabtali part).7.20 5.500.00 5.50 0.00 0.00 6 139.60 0 0.00 110402007 Naruamala G.C - Matidali N.H.Road(Gabtali part).4.60 7.606.80 0.80 0.00 0.00 24 66.29 4 4.20 110402010 Bagbari -Sonahata G.C.C. Road (Gabtali part)3.80 2.701.72 0.98 0.00 0.00 1 0.60 3 24.00 110402011 Fulbari G.C-Tarnir hat G.C.C Road(Gabtali part)3.10 8.208.20 0.00 0.00 0.00 1 2.50 2 180.00 110402012 Naruamala G.C-Fulbari G.C.C.Road(Gabtali Part)3.50 6.505.10 1.40 0.00 0.00 5 105.20 3 25.00 110402013 Naruamala G.C. - Pirgacha G.C. -

View IFT /PQ / REOI / RFP Notice Details

View IFT /PQ / REOI / RFP Notice Details Ministry : Ministry of Housing and Division : Public Works Organization : Public Works Department Procuring Entity Name Bogra pwd division (PWD) : Procuring Entity Code : Procuring Entity Bogura District : Procurement Nature : Works Procurement Type : NCT Event Type : TENDER Invitation for : Tender - Single Lot Invitation Reference 995 Date: 07/02/2019 No. : App ID : 149776 Tender/Proposal ID : 281216 Key Information and Funding Information : Procurement Method : Open Tendering Method Budget Type : Development (OTM) Source of Funds : Government Particular Information : Project Code : 560 / mosques Project Name : Establishing 560 model mosques and Islamic Cultural Centers in Zila and Upazila of Bangladesh Tender/Proposal DB 08_2018-19 Package No. and Construction of Nandigram Upazila Model Mosques and Islamic Cultural Center Description : under the project of Establishing 560 model mosques and Islamic Cultural Centers in Zila and Upazila of Bangladesh Category : Construction work;Site preparation work;Building demolition and wrecking work and earthmoving work;Test drilling and boring work;Works for complete or part construction and civil engineering work;Building construction work;Engineering works and construction works;Construction work for pipelines, communication and power lines, for highways, roads, airfields and railways; flatwork;Construction work for water projects;Construction works for plants, mining and manufacturing and for buildings relating to the oil and gas industry;Roof works and -

Sustainable Rural Infrastructure Improvement Project

Environmental Monitoring Report Project Number: 40515-013 Semi-annual Report January to June 2017 2696-BAN(SF): Sustainable Rural Infrastructure Improvement Project Prepared by Local Government Engineering Department (LGED) for the People’s Republic of Bangladesh and the Asian Development Bank. This environmental monitoring report is a document of the borrower. The views expressed herein do not necessarily represent those of ADB's Board of Directors, Management, or staff, and may be preliminary in nature. In preparing any country program or strategy, financing any project, or by making any designation of or reference to a particular territory or geographic area in this document, the Asian Development Bank does not intend to make any judgments as to the legal or other status of any territory or area. Mott MacDonald Plot 77, Level 6 Block-M Road 11 Banani Dhaka Dhaka 1213 Bangladesh T +880 (2) 986 1194 F +880 (2) 986 0319 mottmac.com/international- development Local Government Engineering Department Sustainable Rural Infrastructure (LGED) RDEC Bhaban (Level-6) Improvement377583 1 project0 (SRIIP) Agargaon, Sher-e-Bangla C:\Users\RAN58195\AppData\Local\Microsoft\Windows\Temporary Internet nagar Dhaka-1207, Files\Content.Outlook\8QF6OYF8\377583-Semi-Annual Environmental Report2017.docx Mott MacDonald Bangladesh D & SC Semi-Annual Environmental Report under SRIIP for the Period of January 2017 – June 2017 Euroconsult Mott MacDonald bv is a member of the Mott MacDonald Group. Registered in The Netherlands no. Local Government Engineering Department -

Phone No. Upazila Health Center

District Upazila Name of Hospitals Mobile No. Bagerhat Chitalmari Chitalmari Upazila Health Complex 01730324570 Bagerhat Fakirhat Fakirhat Upazila Health Complex 01730324571 Bagerhat Kachua Kachua Upazila Health Complex 01730324572 Bagerhat Mollarhat Mollarhat Upazila Health Complex 01730324573 Bagerhat Mongla Mongla Upazila Health Complex 01730324574 Bagerhat Morelganj Morelganj Upazila Health Complex 01730324575 Bagerhat Rampal Rampal Upazila Health Complex 01730324576 Bagerhat Sarankhola Sarankhola Upazila Health Complex 01730324577 Bagerhat District Sadar District Hospital 01730324793 District Upazila Name of Hospitals Mobile No. Bandarban Alikadam Alikadam Upazila Health Complex 01730324824 Bandarban Lama Lama Upazila Health Complex 01730324825 Bandarban Nykongchari Nykongchari Upazila Health Complex 01730324826 Bandarban Rowangchari Rowangchari Upazila Health Complex 01811444605 Bandarban Ruma Ruma Upazila Health Complex 01730324828 Bandarban Thanchi Thanchi Upazila Health Complex 01552140401 Bandarban District Sadar District Hospital, Bandarban 01730324765 District Upazila Name of Hospitals Mobile No. Barguna Bamna Bamna Upazila Health Complex 01730324405 Barguna Betagi Betagi Upazila Health Complex 01730324406 Barguna Pathargatha Pathargatha Upazila Health Complex 01730324407 Barguna Amtali Amtali Upazila Health Complex 01730324759 Barguna District Sadar District Hospital 01730324884 District Upazila Name of Hospitals Mobile No. Barisal Agailjhara Agailjhara Upazila Health Complex 01730324408 Barisal Babuganj Babuganj Upazila Health -

Diversity of Cropping Pattern in Bogra

Bangladesh Rice J. 21 (2) : 73-90, 2017 Diversity of Cropping Pattern in Bogra A B M J Islam1*, S M Shahidullah1, A B M Mostafizur1 and A Saha1 ABSTRACT With a view to document the existing cropping patterns, cropping intensity and crop diversity, a study was carried out over all the upazilas of Bogra agricultural region during 2015-16. A pre-tested semi-structured questionnaire was properly used for this purpose. In the findings it was recorded that 21.88% of net cropped area (NCA) of the region was occupied by the cropping pattern Boro−Fallow−T. Aman. This pattern was found to be distributed over 27 upazilas out of 35. The second largest area, 13.26% of NCA, was covered by Potato−Boro−T. Aman, which was spread over 17 upazilas. A total of 177 cropping patterns were identified in the whole region in this investigation. The highest number of cropping patterns was identified 36 in Nandigram upazila and the lowest was six in Dupchachia and Kahalu upazila of Bogra district. The lowest crop diversity index (CDI) was reported 0.718 in Raiganj upazila of Sirajganj district followed by 0.734 in Kalai of Joypurhat. The highest value of CDI was observed 0.978 in Pabna sadar followed by 0.972 in Bera upazila. The range of cropping intensity values was recorded 183-291%. The maximum value was for Khetlal upazila of Joypurhat district and minimum for Bera of Pabna. As a whole the CDI of Bogra region was calculated 0.966 and the average cropping intensity at regional level was 234%. -

Local Government Engineering Department Office of the Executive Engineer

Government of the People’s Republic of Bangladesh Local Government Engineering Department Office of the Executive Engineer District: Bogura Dbœq‡bi MYZš¿ ¿ www.lged.gov.bd ‡kL nvwmbvi g~jgš Memo No.: 46.02.1000.000.14.044.21.400 Date : 14.02.2021 e-Tender Notice No:14/2020-21 e-Tender is invited in the National e-GP System Portal (https://www.eprocure.gov.bd) for the procurement of following works are given below : Sl. Name of the Scheme with Package No Last Closing & Tender No Selling Opening Proposal ID . Date and Date and & Upazila Time Time 1 548253 01.Rehabilitation of Upazila Hospital-Girls High School (Adamdighi 03/03/2021 04/03/2021 (LTM) Abadpukur By pass) Road from Ch.00-675m .Road ID.110064036 Under Up to Up to Shibganj Adamdighi Upazila District: Bogura 02. Improvement of koribari- Jibonpur 17.00 PM 13.00 PM Road from Ch. 630-1410m. Road ID # 110945008 . (Salvage Value BDT.82268.00). Under Shibgonj Upazila District: Bogura. (Package No: GPBRIDP/MW-130.c) 2 548254 a) Improvement of Kodbour- Nasaratpur via Dumurigram road at (LTM) Ch.1170-2160.00m & 2400-2510.00m. [Road ID # 110062012] b) Adamdighi Construction of 03 Nos U-Drain Size 625mmx600mm at Ch.1402m, 1915m & 2155m. c) Construction of Surface Drain Length-55m Ch.1170m-1232m on Same Road. [DPP SL No-1510] Under Adamdighi Upazila District: Bogura.(Total cost of Salvage Materials TK. 3,54,419.00) .(Package No: RDRIDP/Bogura/Adamdighi-03/19-20) 3 548255 Improvement of Atashi Govt Primary School Connecting Road at Ch. -

40515-013: Environmental Monitoring Report

Environmental Monitoring Report Project Number: 40515-013 Annual Report June 2015 2696-BAN(SF): Sustainable Rural Infrastructure Improvement Project Prepared by Local Government Engineering Department (LGED) for the People’s Republic of Bangladesh and the Asian Development Bank. This environmental monitoring report is a document of the borrower. The views expressed herein do not necessarily represent those of ADB's Board of Directors, Management, or staff, and may be preliminary in nature. In preparing any country program or strategy, financing any project, or by making any designation of or reference to a particular territory or geographic area in this document, the Asian Development Bank does not intend to make any judgments as to the legal or other status of any territory or area. Table of Contents 1. INTRODUCTION .................................................................................................................................... 4 2. PROJECT LOCATION AND COMPONENTS ............................................................................................ 4 3. ENVIRONMENTAL RESPONSIBILITIES AND INSTITUTIONAL SET UP .................................................... 5 4. PROJECT STATUS (CIVIL WORKS AND EMP IMPLEMENTATION) ......................................................... 6 5. COMPLIANCE WITH ENVIRONMENT RELATED PROJECT COVENANTS................................................ 7 6. ENVIRONMENTAL MONITORING REQUIREMENTS ............................................................................. 10 7. ENVIRONMENTAL -

PROCUREMENT PLANNING and MONITORING FORMAT Public Disclosure Authorized

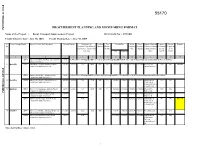

Date : 03 December, 2005 PROCUREMENT PLANNING AND MONITORING FORMAT Public Disclosure Authorized Name of the Project : Rural Transport Improvement Project IDA Credit No. : 3791-BD Credit Effective Date : July 30, 2003 Credit Closing Date : June 30, 2009 #DIV/0! Sl. Contract Package Number* Name of Contract (Brief Description) Quantity/ Number Estimated Cost Procedure/ Prior Planned Date Actual Date of Supplier's Name OR Progress of Financial Remarks No. (in million Taka) OR Actual Method Review** Completion Contract Contractor's Name Procurement Progress as Contract Price (with Contract (Yes/No) Date Signing OR Consultant's as of 30 of 30 Currency) Start Completion Name Nov'09 Nov'09 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 UZR-1.1 Improvement of Ghior-Jabra Road and construction of 8.00 Km The Slice UZR-1.1 of Package Man/UZR-1 has been merged into Package Man/UZR-49 (Sl. No. 49) as a part of single package and transferred from 1st Phase to 2nd Phase. Public Disclosure Authorized appurtenant structures. 01. Man/UZR-1 UZR-1.2 Improvement of Balirteck-Harirampur Road and 3.01 Km 3.01 Km 14.07 14.07 NCB Yes1 1/18/2004 7/21/2005 7/21/2005 10/25/2003 M/S Good Luck 100% 100% Completed construction of appurtenant structures. Trading Corporation UZR-2.1 Improvement of Kaliganj - Jamalpur road and 3.65 Km The Slice UZR-2.1 of Package Gaz/UZR-2 has been shifted to Package Gaz/UZR-32, Slice No. -

List of Upazila Roads 21 Districts Under Rural Transport Improvement Project (RTIP)

E691 Volume 11 GOVERNMENT OF THE PEOPLE'S REPUBLIC OF BANGLADESH Public Disclosure Authorized MINISTRY OF LOCAL GOVERNMENT, RURAL DEVELOPMENT & CO-OPERATIVES Rural Transport Improvement Project L '~.r-r-: Public Disclosure Authorized A-9~~~~F Public Disclosure Authorized Borrower's Project Implementation Plan (BPIP) (Volume-l of 11) Local Government Engineering Department Public Disclosure Authorized April 2003 Table of Contents I. I ntroduction ........................... .................................. I 11. The Project ............................................................. 2 A. Project Scope and Objectives ............................................................. 2 B. Detailed Project Description .............................................................. 3 C. Economic and Financial Analyses of Project ..................... ....................... 11 D. Assessment of Project Risks (Intenial & External) .................... ........... .. 14 E. Cost Estimates and Financinig Plan ............................................................ 16 Ill. Implementation Arrangements ............................................................. 17 A. Project Implementation Organizations ......................................... ....... 17 B. Administrative Arrangements for the Project Management ......... ........... 18 C. Management of Project Procurement ...................................................... 19 D. Implementation Arrangement for Works .................................................. 20 E. Implementation Arrangement