165 Master Hartmann and Ulm at the Beginning of the 15Th Century

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Geometric Proportioning Strategies in Gothic Architectural Design Robert Bork*

$UFKLWHFWXUDO Bork, R 2014 Dynamic Unfolding and the Conventions of Procedure: Geometric +LVWRULHV Proportioning Strategies in Gothic Architectural Design. Architectural Histories, 2(1): 14, pp. 1-20, DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.5334/ah.bq RESEARCH ARTICLE Dynamic Unfolding and the Conventions of Procedure: Geometric Proportioning Strategies in Gothic Architectural Design Robert Bork* This essay explores the proportioning strategies used by Gothic architects. It argues that Gothic design practice involved conventions of procedure, governing the dynamic unfolding of successive geometrical steps. Because this procedure proves difficult to capture in words, and because it produces forms with a qualitatively different kind of architectural order than the more familiar conventions of classical design, which govern the proportions of the final building rather than the logic of the steps used in creating it, Gothic design practice has been widely misunderstood since the Renaissance. Although some authors in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries attempted to sympathetically explain Gothic geometry, much of this work has been dismissed as unreliable, especially in the influential work of Konrad Hecht. This essay seeks to put the study of Gothic proportion onto a new and firmer foundation, by using computer-aided design software to analyze the geometry of carefully measured buildings and original design drawings. Examples under consideration include the parish church towers of Ulm and Freiburg, and the cross sections of the cathedrals of Reims, Prague, and Clermont-Ferrand, and of the Cistercian church at Altenberg. Introduction of historic monuments to be studied with new rigor. It is Discussion of proportion has a curiously vexed status in finally becoming possible, therefore, to speak with reason- the literature on Gothic architecture. -

Achim Timmermann of Often Staggering Size and Great Formal Vir- Tuosity, and Looming Over the Skylines of Many European Cities E

Buchrezension 29. November 2005 Book Review Editor: R. Donandt Robert Bork, Great Spires: Skyscrapers of the New Jerusalem. Kölner Architekturstudien, 76. Köln: Abteilung Architekturgeschichte des Kunsthistorischen Instituts der Universität zu Köln 2003. 504 p. Numerous b/w illustrations and plans. ISBN 0615128300. Achim Timmermann Of often staggering size and great formal vir- exchange that gave great spire design its unique- tuosity, and looming over the skylines of many ness and innovative momentum. Assessing the European cities even today, the spire was by far symbolic signifi cance these colossal structures the most conspicuous feature of the high and late would have had for their medieval audiences, the Gothic church. Curiously, however, it has also re- author remarks that in their heavenward push and mained one of the least researched. This splendid aesthetic complexity spires referenced and glori- study represents the fi rst book-length monograph fi ed both, the City of God, and worldly authori- on this important, but much-neglected subject. ty; spires therefore simultaneously visualized a Bork‘s chief interest concerns what he calls ‚the theological concept, and the interests, needs and great spire‘ - a descriptive category developed in aspirations of those powerful institutions that had analogy to Christopher Wilson‘s notion of ‚the initiated their construction. To characterize this great church‘ [1] - and here referring to spires of dual function, the author coins the catching phra- considerable formal, geometrical, and structural se ‚skyscrapers of the New Jerusalem‘. intricacy - essentially those of the cathedrals and great burgher churches in France, the Low Coun- In its assessment of the very relationship bet- tries, the Rhineland, and the southern parts of the ween built spire and ‚New‘ or ‚Heavenly‘ Jeru- German-speaking lands. -

Liebe Schützenschwestern Und Schützenbrüder

Liebe Schützenschwestern und Schützenbrüder, die RWK- Saison 2010 / 2011 ist abgeschlossen. Nachdem nun die letzten Wettkampfprotokolle eingingen, hier die Abschlusstabelle. Es wurden wieder sehr gute Ergebnisse erzielt. Ich hoffe dass auch die Kameradschaft bei den Wettkämpfen nicht zu kurz kam. Ich danke allen für die engagierte Teilnahme, ganz besonders den Mannschaftsführern für die pünktliche und schnelle Übermittlung der Wettkampfergebnisse. Bis zur RWK- Saison 2011 / 2012 verbleibe ich mit einem Gut Schuß Rundenwettkampf 2010 / 11 Kreisklasse Ulm - LG- u. LP-Klasse Abschlusstabelle Mannschaftswertung A-Klasse Luftgewehr LNr. Gesamt Schnitt Verein 1.RWK 2.RWK 3.RWK 4.RWK 5.RWK 6.RWK 1 8670 1445 Weidenstetten 1 1458 1418 1461 1439 1435 1459 2 8599 1433,17 Rammingen 1 1433 1421 1462 1412 1434 1437 3 8554 1425,67 Asch 3 1399 1431 1434 1425 1441 1424 4 8542 1423,67 Arnegg 1 1428 1423 1409 1417 1434 1431 5 8533 1422,17 Langenau 2 1431 1389 1447 1427 1427 1412 6 8531 1421,83 Machtolsheim 3 1410 1425 1416 1431 1417 1432 7 8513 1418,83 Neenstetten 1 1413 1409 1422 1432 1421 1416 8 8505 1417,5 Schnürpflingen 2 1407 1447 1415 1408 1421 1407 9 8492 1415,33 Ettlenschieß 2 1423 1422 1406 1434 1407 1400 10 8465 1410,83 Altheim / Weihung 5 1411 1401 1391 1446 1421 1395 11 8450 1408,33 Unterkirchberg 1394 1422 1389 1397 1416 1432 12 8449 1408,17 Erbach 1389 1407 1410 1422 1428 1393 13 8428 1404,67 Albeck 2 1412 1437 1376 1402 1422 1379 14 8391 1398,5 Neenstetten 2 1396 1423 1407 1391 1373 1401 15 8302 1383,67 Illerrieden 2 1405 1404 1405 1370 1377 1341 16 8301 1383,5 Scharenstetten Dam 1368 1413 1356 1409 1378 1377 17 8230 1371,67 Bernstadt 2 1384 1366 1370 1376 1362 1372 18 8215 1369,17 Ermingen 2 1385 1362 1378 1349 1369 1372 19 8148 1358 Weidenstetten 2 1373 1363 1387 1278 1385 1362 20 8141 1356,83 Altheim / Alb 1391 1370 1334 1351 1357 1338 Seite 1 von 16 Mannschaftswertung B-Klasse Luftgewehr LNr. -

Munderkinger Donaubote AMTSBLATT DER STADT MUNDERKINGEN Freitag, 30

Munderkinger Donaubote AMTSBLATT DER STADT MUNDERKINGEN Freitag, 30. April 2021/Nr. 17 Liebe Mitglieder, liebe Freunde und Gönner der Trommgesellenzunft Munderkingen e.V. Wir hatten in diesem Jahr 2021 eine Fasnet, die es so noch nie gab – für uns alle wird diese mit Sicherheit unvergesslich bleiben. DANKE, dass Ihr alle Teil davon wart! Einen Rückblick auf das vergangene Vereinsjahr gibt es eigentlich immer jährlich auf der Hauptversammlung. Diese kann nun leider auch in diesem Jahr nicht wie gewohnt Ende April stattfinden und wird auf einen späteren Termin verschoben. Uns ist es allerdings ein großes Bedürfnis, dass wir uns nun auf diesem Wege für die grandiose Unterstützung bei unserer gemeinsamen „Fasnet dahoim“ bei allen bedanken können - ganz gleich ob als Organisator, Mitwirkende oder als Zuschau- er. Unsere Ideen und Angebote wurden von Euch offen und engagiert mit uns umgesetzt, weiterentwickelt, mitgetragen, zur Fasnet gemacht. Wir freuen uns, dass dadurch so Vieles möglich und das Fasnetsgefühl erlebbar wurde. Um nochmals selbst auf die Fasnet und die vielen unterschiedlichen Aktionen blicken zu können, haben wir auf unserer Homepage www.narro-hee.de eine klei- ne Bilderauswahl zusammengestellt. Ebenfalls sind hier auch alle Videos sowie ein Großteil der unterschiedlichsten Bildeinsendungen der verschiedensten Aktionen zu finden. Die Vorfreude, wieder mit allen Mitgliedern, Mäschgerla und Fasnetsfreunden gemeinsam feiern, schunkeln und maschgern zu können und auf die Möglichkeit vieler persönlichen Begegnungen, ist groß! Bis dahin laden wir ein, beim nächsten Besuch im Städtle unsere Schaufenster am Zunfthaus in der Martinstraße anzuschauen. Bei unserer Aktion „Fasnet anno dazumal“ kamen erstaunliche Schätze zusammen und diese möchten wir Euch keinesfalls vorenthalten. -

Proquest Dissertations

Pestilence and Reformation: Catholic preaching and a recurring crisis in sixteenth-century Germany Item Type text; Dissertation-Reproduction (electronic) Authors Frymire, John Marshall Publisher The University of Arizona. Rights Copyright © is held by the author. Digital access to this material is made possible by the University Libraries, University of Arizona. Further transmission, reproduction or presentation (such as public display or performance) of protected items is prohibited except with permission of the author. Download date 07/10/2021 19:47:39 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/279789 INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand comer and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overiaps. Photographs included in the original manuscript have been reproduced xerographically in this copy. Higher quality 6" x 9" black and white photographic prints are available for any photographs or illustrations appearing in this copy for an additional charge. -

Call for Papers for the 16Th German LS-DYNA Forum

DYNAmore GmbH Gesellschaft für FEM Press Release 2/2020 Ingenieurdienstleistungen Call for Papers for the 16th German LS-DYNA Forum Stuttgart, March 3rd, 2020 Every two years DYNAmore GmbH invites all users from industry and academia to the German LS-DYNA Forum. This year the event will take place from 7-9 October 2020 in Ulm. The forum is the ideal framework for exchanging knowledge and experience with LS-DYNA and related products. With the "Call for Papers" DYNAmore invites all users to submit their work with LS-DYNA or LS-OPT and to present it to an international expert audience at the major event on simulation with LS-DYNA in Germany. The deadline for submissions is 29 May 2020; all that is needed to submit a paper is the title and a brief description of the presentation. These can be easily submitted via the website at www.dynamore.de/abstract-2020-e. Please note that the forum does not require a paper of several pages, a two-page abstract is sufficient. In addition, DYNAmore will publish the slides on its website after the conference and therefore asks for the presentations to be made available. The technical presentations are the core of the conference. But first-class keynote presentations by top-class speakers from industry and academia are also again on the agenda. Software developers from LST, an ANSYS Company, will also be represented there and inform about the latest trends and developments in LS-DYNA. The range of topics will be rounded off by the popular workshops on various topics and applications. -

Dornstadt-Temmenhausen (DB/A8) - Alb-Donau-Kreis

Anordnungsbeschluss (DB/A8) Dornstadt-Temmenhausen (DB/A8) - Alb-Donau-Kreis Flurbereinigungsbeschluss v om 24.07.2008 Aufgrund von § 4 des Flurbereinigungsgesetzes (FlurbG) in der Fassung vom 16.03.1976 (BGBl. I S. 546) ordnet hiermit das Regierungspräsidium Stuttgart, Landesamt für Flurneuordnung, die Flurbereinigung Dornstadt-Temmenhausen (DB/A 8) nach § 87 FlurbG an. Sie wird vom Landratsamt Alb-Donau-Kreis - untere Flurbereinigungsbehörde - durchgeführt. Das Flurbereinigungsgebiet umfasst von der Gemeinde Dornstadt die Gemarkung Temmenhausen. Ausgeschlossen sind die Ortslage einschließlich der von der Bauleitplanung betroffenen Flächen sowie die geschlossenen Waldflächen, soweit sie nicht von den Unternehmen „Ausbau der A 8 Karlsruhe - München, Streckenabschnitt Hohenstadt - Ulm-West“ und „Ausbau- und Neubau der DB-Strecke Stuttgart - Augsburg, Bereich Wendlingen - Ulm, Planfeststellungsabschnitt PFA 2.3 Albhochfläche“ betroffen sind. Es wird mit einer Fläche von rd. 623 ha in dem aus der Gebietskarte und der Gebietsübersichtskarte, je vom 16.06.2008, näher ersichtlichen Umfang festgestellt. Die Begründung, die Gebietskarte und die Gebietsübersichtskarte sind Bestandteile dieses Beschlusses. 2. Am Flurbereinigungsverfahren sind beteiligt - als Teilnehmer die Eigentümer und die Erbbauberechtigten der zum Flurbereinigungsgebiet gehörenden Grundstücke. Sie bilden die Teilnehmergemeinschaft. - als Nebenbeteiligte die Inhaber von Rechten an den zum Flurbereinigungsgebiet gehörenden Grundstücken sowie die Eigentümer von nicht zum Flurbereinigungsgebiet -

81984-1B SP.Pdf

Poetics of Place How Ancient Buildings Inspired Great Writing Bassim Hamadeh, CEO and Publisher Jennifer Codner, Acquisitions Editor Michelle Piehl, Project Editor Sean Adams, Production Editor Miguel Macias, Senior Graphic Designer Stephanie Kohl, Licensing Associate Natalie Piccotti, Senior Marketing Manager Kassie Graves, Vice President of Editorial Jamie Giganti, Director of Academic Publishing Copyright © 2018 by Elizabeth Riorden. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be re- printed, reproduced, transmitted, or utilized in any form or by any electronic, mechanical, or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying, microfilming, and recording, or in any information retrieval system without the written permission of Cognella, Inc. For inquiries regarding permissions, translations, foreign rights, audio rights, and any other forms of reproduc- tion, please contact the Cognella Licensing Department at [email protected]. Trademark Notice: Product or corporate names may be trademarks or registered trademarks, and are used only for identification and explanation without intent to infringe. Cover image copyright © 2017 iStockphoto LP/mammuth. Printed in the United States of America. ISBN: 978-1-5165-1754-1 (pbk) / 978-1-5165-1755-8 (br) First Edition Poetics of Place How Ancient Buildings Inspired Great Writing edited by Elizabeth Riorden University of Cincinnati To my parents, and to my teachers Contents Literary Sources ..................................................................vii Foreword -

Nellinger Mitteilungsblatt – Erscheinungstag Ist Immer

53. Jahrgang Freitag, 3. März 2017 Nummer 9 Wohnung zur Miete gesucht! Evangelisches Pfarramt Die Gemeinde Nellingen sucht für eine anerkannte fünf-, bald sechsköpfige Asylbewerberfamilie aus dem Irak eine 4- bis 5-Zimmerwohnung. Mietzahlungen können sichergestellt werden. Weitere Fragen beantwortet Ihnen gerne Herr Bürgermeister Franko Kopp, Tel.: 963080 oder die Sachbearbeiterin Frau Scheifele, Tel.: 963020. Gemeindeverwaltung Nellingen Weltgebetstag am Freitag, 03. März 2017 19:30 Uhr Michaelskirche Oppingen Nellinger Mitteilungsblatt – Erscheinungstag „Was ist denn fair?“ ist immer freitags Die Liturgie haben Frauen von den Philippinen vorbereitet. An alle Nutzer des Textportals! Erleben Sie den Abend bei Texten, Musik, Bildern und Spe- Bitte geben Sie keine Texte ein, die sich auf Termine beziehen, die zialitäten von den Philippinen. vor dem Erscheinungstag liegen. Frauen aller Konfessionen sind herzlich eingeladen! Das Mitteilungsblatt wird teilweise erst am Freitag ausgetragen. Besser ist es, wenn Sie die Texte bereits eine Woche zuvor ein- geben. Danke! Gemeindeverwaltung Nellingen Öffentlicher Personennahverkehr – Änderun- gen bei der Buslinie Ulm-Dornstadt-Nellingen Wie bereits angekündigt, werden wir nach den Faschingsferien, Ferienbetreuung in den Sommerferien 2017 d.h. ab 06.03.2017 verschiedene Änderungen umsetzen. Im Wesentlichen sind folgende Änderungen zu nennen: BITTE MELDEN SIE IHR KIND SO FRÜH WIE MÖGLICH - Anpassung der Fahrzeiten zur Steigerung der Pünktlichkeitsrate AN, DAMIT WIR FESTSTELLEN KÖNNEN, OB ÜBER- generell HAUPT BEDARF BESTEHT! - Erweiterung der Buskapazitäten in der Hauptverkehrszeit Die Gemeinde Nellingen möchte erneut, bei ausreichendem - Beginn 1. UStd. = Direktbus der Linie 49 (Fahrt 49014) verkehrt neu weiter bis Ulm Kuhberg Schulzentrum (nur zum Ausstieg) Interesse (mindestens 5 angemeldete Kinder), eine Ferienbe- - Mit späterer Abfahrt in Ulm um 13:25 Uhr (bisher 13:15/13:18) treuung im Kindergarten anbieten. -

Ulm . Neu-Ulm Ulm

Höhlen, Quellen, Archäologie ulm . neu-ulm ulm . neu-ulm Alles at a glance auch online Rund buchbar Informative City-Guide · ENGLISH with herum city … aber auch kreuz und quer, von hüben nach Größer. Tiefer. Älter. map drüben und zurück führen wir Sie durch Ulm und Neu-Ulm. Kurzweilig, informativ und oft auch mit einem besonderen Augenzwinkern Bei uns finden Sie alle zeigen wir Ihnen bei unseren vielen Stadt- und Erlebnisführungen die schönsten Seiten der Superlative! beiden Städte. Karstquelle Blautopf Blaubeuren Und für bleibende Erinnerungen an die Donau- Doppelstadt sorgen unsere tollen Souvenirs, Die schönste Karstquelle Deu tsch- die wir Ihnen in unserer Tourist-Information lands mit dem größten Höhlen system präsentieren. der Schwäbischen Alb. Tourist-Information Ulm/Neu-Ulm Münsterplatz50 (Stadthaus) · 89073 Ulm Telefon 0731 161-2830 Tiefenhöhle Laichingen Reise ins Innere der Erde. Die tiefste Schauhöhle Deutschlands (55 m tief). Urgeschichtliches Museum Blaubeuren Die älteste Kunst. Elfenbeinschnitzereien aus den Steinzeithöhlen der Alb, bis zu 40.000 Jahre alt. Broschüre „höhlenreich“ bestellen! Alb-Donau-Kreis Tourismus Schillerstraße 30 · 89077 Ulm Telefon 0731/185-1238 www.tourismus.alb-donau-kreis.de www.tourismus.ulm.de [email protected] www.tourismus.ulm.de City map The numbers in the map refer to the sights in the broschure. 41 Botanical Garden (ca. 2 km) Friedrichsau Park (ca. 1,5 km) 40 18 19 45 34 7 8 22 47 33 Blaustein (ca. 7 km) 7 (ca. Blaustein 26 1 29 28 31 4 20 21 13 2 15 14 11 17 27 5 Cloister Courtyard (ca. 2,5 km) 2,5 (ca. -

Welcome to Southwest Germany

WELCOME TO SOUTHWEST GERMANY THE BADEN-WÜRTTEMBERG VACATION GUIDE WELCOME p. 2–3 WELCOME TO SOUTHWEST GERMANY In the heart of Europe, SouthWest Germany Frankfurt Main FRA (Baden-Württemberg in German) is a cultural crossroads, c. 55 km / 34 miles bordered by France, Switzerland and Austria. But what makes SouthWest Germany so special? Mannheim 81 The weather: Perfect for hiking and biking, NORTHERN BADENWÜRTTEMBERGJagst Heidelberg from the Black Forest to Lake Constance. 5 Neckar Kocher Romantic: Some of Europe’s most romantic cities, 6 Andreas Braun Heilbronn Managing Director such as Heidelberg and Stuttgart. Karlsruhe State Tourist Board Baden-Württemberg Castles: From mighty fortresses to fairy tale palaces. 7 Pforzheim Christmas markets: Some of Europe’s most authentic. Ludwigsburg STUTTGART Karlsruhe REGION Baden-Baden Stuttgart Wine and food: Vineyards, wine festivals, QKA Baden-Baden Michelin-starred restaurants. FRANCE STR Rhine Murg Giengen Cars and more cars: The Mercedes-Benz 8 an der Brenz Outletcity and Porsche museums in Stuttgart, Ki n zig Neckar Metzingen Ulm Munich the Auto & Technik Museum in Sinsheim. MUC SWABIAN MOUNTAINS c. 156 km / 97 miles 5 81 Hohenzollern Castle Value for money: Hotels, taverns and restaurants are BLACK FOREST Hechingen Danube Europa-Park BAVARIA7 well-priced; inexpensive and efficient public transport. Rust Real souvenirs: See cuddly Steiff Teddy Bears Danube and cuckoo clocks made in SouthWest Germany. Freiburg LAKE CONSTANCE REGION Spas: Perfect for recharging the batteries – naturally! Black Forest Titisee-Neustadt Titisee Highlands Feldberg 96 1493 m Schluchsee 98 Schluchsee Shopping: From stylish city boutiques to outlet shopping. Ravensburg Mainau Island People: Warm, friendly, and English-speaking. -

Problemstoffsammlung Endgültiger Fahrplan 2017

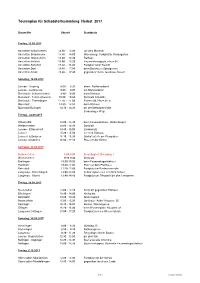

Tourenplan für Schadstoffsammlung Herbst 2017 Datum/Ort Uhrzeit Standplatz Freitag, 15.09.2017 Amstetten-Schalkstetten 13.00 - 13.20 vor dem Museum Amstetten-Bräunisheim 13.40 - 14.00 Wiesenweg, Parkplatz b. Kindergarten Amstetten-Stubersheim 14.20 - 14.40 Rathaus Amstetten-Hofstett 15.00 - 15.20 Feuerwehrmagazin, Neue Str. Amstetten-Bahnhof 15.40 - 16.20 Parkplatz beim Bauhof Amstetten-Dorf 16.40 - 17.00 beim Backhaus (Spitalgasse) Amstetten-Reutti 17.20 - 17.40 gegenüber ehem. Gasthaus Rössle Samstag, 16.09.2017 Lonsee - Urspring 8.00 - 8.30 ehem. Raiffeisenbank Lonsee - Luizhausen 8.50 - 9.20 am Brunnenplatz Dornstadt - Scharenstetten 9.40 - 10.00 beim Rathaus Dornstadt - Temmenhausen 10.20 - 10.50 Dorfplatz Ortsmitte Dornstadt - Tomerdingen 11.10 - 11.50 Farrenstall, Neue Str. 6 Dornstadt 12.50 - 13.50 beim Rathaus Dornstadt-Bollingen 14.10 - 14.30 bei der Mehrzweckhalle Bermaringer Weg Freitag, 22.09.2017 Altheim/Alb 13.00 - 13.40 beim Feuerwehrhaus, Hindenburgstr. Weidenstetten 14.00 - 14.20 Dorfplatz Lonsee - Ettlenschieß 14.40 - 15.00 Lindenplatz Lonsee 15.20 - 15.50 vor dem Rathaus Lonsee-Halzhausen 16.10 - 16.30 Bushaltestelle am Kiesgraben Lonsee- Sinabronn 16.50 - 17.10 Platz vor der Kirche Samstag, 23.09.2017 Beimerstetten 8:00-8:50 Recyclinghof, Dolenweg 1 Westerstetten 9:10-9:40 Dorfplatz Breitingen 10:00-10:20 beim Feuerwehrgerätehaus Holzkirch 10:40-11:00 Platz vor dem Pfarrhaus Bernstadt 11:20-12:00 Parkplatz bei Riedwiesenhalle Langenau - Hörvelsingen 13:00-13:20 Schmiedgasse bei der Alten Schule Langenau - Albeck 13:40-14:10 Parkplatz am Flötzbach bei den Containern Freitag, 29.09.2017 Neenstetten 13.00 - 13.20 Dorfplatz gegenüber Rathaus Börslingen 13.40 - 14.00 Kirchplatz Ballendorf 14.20 - 14.40 Brunnenplatz Nerenstetten 15.00 - 15.20 Gasthaus "Adler" Hauptstr.