Ret 56 Cover & TOC Copie

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Calendar-Year Dating of the Greenland Ice Sheet Project 2 (GISP2) Ice Core from the Early Sixth Century Using Historical, Ion, and Particulate Data

spe505-22 1st pgs page 411 The Geological Society of America Special Paper 505 2014 Calendar-year dating of the Greenland Ice Sheet Project 2 (GISP2) ice core from the early sixth century using historical, ion, and particulate data Dallas H. Abbott Dee Breger† Pierre E. Biscaye Lamont-Doherty Earth Observatory of Columbia University, Palisades, New York 10964, USA Robert A. Juhl Independent researcher, 1-4-1 Rokko Heights, 906 Shinkawa, Chuo-ku, Tokyo 104-0033, Japan ABSTRACT We use the occurrence of unusual or out-of-season dust storms and dissolved ion data as proxies for dust to propose a calendar-year chronology for a portion of the Greenland Ice Sheet Project 2 (GISP2) ice core during the early sixth century A.D. Our new time scale moves a small sulfate peak to early 537 A.D., which is more con- sistent with recent fi ndings of a 6 mo to 18 mo time lag between volcanic eruptions and atmospheric fallout of their sulfate aerosols. Our new time scale is consistent with a small volcanic input to the A.D. 536–537 climate downturn. We use the time range of Ni-rich fragments and cosmic spherules to provide an independent test of the chronology. The time range of Ni-rich fragments and cosmic spherules matches historical observations of “dancing stars” starting in the summer of A.D. 533 and lasting until A.D. 539 or 540. These dancing stars have been previously attributed to cosmogenic dust loading of Earth’s atmosphere. The time scale cannot be shifted to be either younger or older by 1 yr without destroying the match to historical accounts of dancing stars. -

High Road to Lhasa Trip

Indian high road to Himalaya Sub-continent lhasa trip highligh ts Journey over the Tibet Plateau to Rongbuk Monastery and Mt. Everest Absorb the dramatic views of the north face of Everest Explore Lhasa and visit Potala Palace, former home of the Dalai Lama Delve into the rich cultural traditions of Tibet, visiting Tashilhunpo Monastery in Shigatse Traverse the Himalaya overland from the Tibetan Plateau to Kathmandu Trip Duration 13 days Trip Code: HRL Grade Adventure touring Activities Adventure Touring Summary 13 day trip, 1 night hotel in Chengdu, 7 nights basic hotels, 2 nights Tibetan lodge, 2 nights Radisson Hotel, Kathmandu welcome to why travel with World Expeditions? When planning travel to a remote and challenging destination, World Expeditions many factors need to be considered. World Expeditions has been Thank you for your interest in our High Road to Lhasa trip. At pioneering trips in the Himalaya since 1975. Our extra attention to World Expeditions we are passionate about our off the beaten track detail and seamless operations on the ground ensure that you will experiences as they provide our travellers with the thrill of coming have a memorable experience in the Indian Sub‑continent. Every trip face to face with untouched cultures as well as wilderness regions is accompanied by an experienced local leader, as well as support staff of great natural beauty. We are committed to ensuring that our that share a passion for the region, and a desire to share it with you. We unique itineraries are well researched, affordable and tailored for the take every precaution to ensure smooth logistics, with private vehicles enjoyment of small groups or individuals ‑ philosophies that have throughout your trip. -

WHV- Protect Swayambhu, Nepal, Volunteers Initiative Nepal

WHV – Protect Swayambhu Kathmandu Valley, Nepal Cultural property inscribed on the 17/09/2016 - 29/09/2016 World Heritage List since 1979 Located in the foothills of the Himalayas, the Kathmandu Valley World Heritage property is inscribed as seven Monument Zones. As Buddhism and Hinduism developed and changed over the centuries throughout Asia, both religions prospered in Nepal and produced a powerful artistic and architectural fusion beginning at least from the 5th century AD, but truly coming into its own in the three-hundred-year-period between 1500 and 1800 AD. These monuments were defined as the outstanding cultural traditions of the Newars, manifested in their unique urban settlements, buildings and structures with intricate ornamentation displaying outstanding craftsmanship in brick, stone, timber and bronze that are some of the most highly © TTC developed in the world. Project objectives: Swayambhu stupa and its surroundings have been dramatically damaged by the 2015 earthquake, and a first World Heritage Volunteers camp has successfully taken place in December of the same year. Following up on the work and partnerships developed, the project aims at supporting the local authorities and experts in the important reconstruction and renovation work ongoing, and at running promotional, and educational activities to further sensitize the local population and visitors about the protection of the site. Project activities: The volunteers will be directly involved in the undergoing renovation work, supporting the local experts and authorities to preserve the area and continue the reconstruction work started after the earthquake. After receiving targeted training by local experts, the participants will also run an educational campaign on the history and importance of the site and its needs and threats, aiming at reaching out to the community and in particular to the students of local universities and colleges. -

Hanwen Fang, a Study of Comparative Civilizations. Beijing: Zhonghua Book Company, 2014

Comparative Civilizations Review Volume 76 Article 21 Number 76 Spring 2017 4-25-2017 Hanwen Fang, A Study of Comparative Civilizations. Beijing: Zhonghua Book Company, 2014. Shi Yuanhui Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/ccr Part of the Comparative Literature Commons, History Commons, International and Area Studies Commons, Political Science Commons, and the Sociology Commons Recommended Citation Yuanhui, Shi (2017) "Hanwen Fang, A Study of Comparative Civilizations. Beijing: Zhonghua Book Company, 2014.," Comparative Civilizations Review: Vol. 76 : No. 76 , Article 21. Available at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/ccr/vol76/iss76/21 This Book Review is brought to you for free and open access by the All Journals at BYU ScholarsArchive. It has been accepted for inclusion in Comparative Civilizations Review by an authorized editor of BYU ScholarsArchive. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. Yuanhui: Hanwen Fang, <em>A Study of Comparative Civilizations</em>. Beiji Comparative Civilizations Review 161 Hanwen Fang, A Study of Comparative Civilizations. Beijing: Zhonghua Book Company, 2014. Reviewed by Shi Yuanhui In 2014, Professor Fang Hanwen of Soochow University, China, published his 5-volumed monograph, A Study of Comparative Civilizations, offering his understanding of the main civilizations in the world. Professor Fang won his doctorate in Beijing Normal University in 1990, and he continued his studies of comparative literature and comparative civilizations, having published 34 books. As he wrote in the epilogue, he had been working on the book, A Study of Comparative Civilizations, since he was still reading for his doctor’s degree and finally completed it when he was invited to be a full-time research fellow in Peking University. -

TIBET - NEPAL Septembre - Octobre 2021

VOYAGE PEKIN - TIBET - NEPAL Septembre - octobre 2021 VOYAGE PEKIN - TIBET - NEPAL Itinéraire de 21 jours Genève - Zurich - Beijing - train - Lhasa - Gyantse - Shigatse - Shelkar - Camp de base de l’Everest - Gyirong - Kathmandu - Parc National de Chitwan - Kathmandu - Delhi - Zurich - Genève ITINERAIRE EN UN CLIN D’ŒIL 1 15.09.2021 Vol Suisse - Beijing 2 16.09.2021 Arrivée à Beijing 3 17.09.2021 Beijing 4 18.09.2021 Beijing 5 19.09.2021 Beijing - Train de Pékin vers le Tibet 6 20.09.2021 Train 7 21.09.2021 Arrivée à Lhassa 8 22.09.2021 Lhassa 9 23.09.2021 Lhassa 10 24.09.2021 Lhassa - Lac Yamdrok - Gyantse 11 25.09.2021 Gyantse - Shigatse 12 26.09.2021 Shigatse - Shelkar 13 27.09.2021 Shelkar - Rongbuk - Camp de base de l'Everest 14 28.09.2021 Rongbuk - Gyirong 15 29.09.2021 Gyirong – Rasuwa - Kathmandou 16 30.09.2021 Kathmandou 17 01.10.2021 Kathmandou - Parc national de Chitwan 18 02.10.2021 Parc national de Chitwan 19 03.10.2021 Parc national de Chitwan - Kathmandou 20 04.10.2021 Vol Kathmandou - Delhi - Suisse 21 05.10.2021 Arrivée en Suisse Itinéraire Tibet googlemap de Lhassa à Gyirong : https://goo.gl/maps/RN7H1SVXeqnHpXDP6 Itinéraire Népal googlemap de Rasuwa au Parc National de Chitwan : https://goo.gl/maps/eZLHs3ACJQQsAW7J7 ITINERAIRE DETAILLE : Jour 1 / 2 : VOL GENEVE – ZURICH (OU SIMILAIRE) - BEIJING Enregistrement de vos bagages au moins 2h00 avant l’envol à l’un des guichets de la compagnie aérienne. Rue du Midi 11 – 1003 Lausanne +41 21 311 26 87 ou + 41 78 734 14 03 @ [email protected] Jour 2 : ARRIVEE A BEIJING A votre arrivée à Beijing, formalités d’immigration, accueil par votre guide et transfert à l’hôtel. -

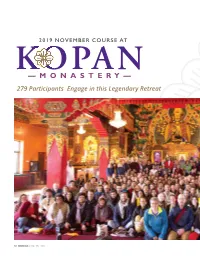

— M O N a S T E R

2019 NOVEMBER COURSE AT KOPAN —MONASTERY— 279 Participants Engage in this Legendary Retreat 52 MANDALA | Issue One 2020 Every year, the November Course, a month-long lamrim meditation course at Kopan Monastery in Kathmandu, Nepal, draws diverse students from around the world. What started in 1971 with a dozen students in attendance, reached a record 279 participants from forty-nine countries this year with Ven. Robina Courtin teaching the course for the first time. This was also the first course held in Kopan’s new Chenrezig gompa. Mandala editor, Carina Rumrill asked Ven. Robina about this year’s course, and we share this beautiful account of her experience and history with this style of retreat. THIS YEAR’S RECORD NUMBER OF PARTICIPANTS — 279 PEOPLE FROM FORTY-NINE COUNTRIES — WITH KOPAN’S ABBOT KHEN RINPOCHE THUBTEN CHONYI, VEN. ROBINA COURTIN, AND OTHER TEACHERS AND MEDITATION LEADERS. PHOTO BY VEN. THUBTEN CHOYING (SARAH BROOKS). Issue One 2020 | MANDALA 53 VEN. ROBINA COURTIN OFFERED A MANDALA TO RINPOCHE REQUESTING TEACHINGS. PHOTO BY VEN. THUBTEN CHOYING (SARAH BROOKS). AND THE BLESSINGS: YOU COULDN’T HELP BUT FEEL THEM BY VEN. ROBINA COURTIN The Kopan November Course is legendary. The first of what But the beauty of the place was its saving grace: a hill became an annual event, one month of lamrim teachings by surrounded on all sides by the terraced fields of the magnifi cent Lama Zopa Rinpoche to a dozen Westerners fifty years ago, Kathmandu Valley, with mountains to the north and the holy quickly became a magnet for spiritual seekers worldwide. -

Common Man's Confucius for the West 10:55, May 08, 2009

Common man's Confucius for the West 10:55, May 08, 2009 When Yu Dan, a media expert and professor at Beijing Normal University, sat down to interpret Confucian thoughts in 2006, little did she realize that this effort would catapult her to overnight fame, turning the wise and dusty old Confucian teachings into a Chinese version of Chicken Soup for the Soul. Yu Dan's Insights into the Analects, based on 7 lectures that Yu Dan gave in 2006 on China Central Television's (CCTV) primetime show "Lecture Room", sold a record 12,600 copies on the launch day. Within two years, the book sold 5 million legal copies and an estimated 6 million pirated ones, remaining at the top of the Chinese bestseller lists even today (ranked 23rd in the non-fiction category in March 2009). While the Chinese version continued to reap in rich harvests, last week, UK-based Macmillan Publishers Ltd, released the English version of Yu Dan's bestseller, Confucius from the Heart: Ancient Wisdom for Today's World, bringing 2500-year-old Confucian wisdom to modern Western readers. Translated from Yu Dan's original book, published by Zhonghua Book Company, which is based in Beijing, the English version has trumped the previous record money of 100,000 U.S. dollars Jiang Rong's Wolf Totem cost Penguin in September 2005. Macmillan has paid a record 100,000 British pounds to Zhonghua for obtaining the copyright of Yu's book. Macmillan published the book in UK on May 1, 2009. To promote her book, Yu Dan visited UK and gave speeches at Cambridge University, Manchester University and Asian House in April, attracting hundreds of British audience.(Photo: en.huanqiu.com) A few years ago, Chinese traditional culture was brought back in vogue by the CCTV show "Lecture Room", triggering nationwide enthusiasm and it also caught the attention of the Western media. -

PHANTOM PHYSICALIZATIONS Reinterpreting Dreams Through Physical Representation

PHANTOM PHYSICALIZATIONS Reinterpreting dreams through physical representation ·······Interaction·Design·Master·Thesis······Vincent·Olislagers······June·2012······K3·School·of·Arts·and·Communication······Malmö·University······· Thesis submitted as fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science in Interaction Design Advisor: David Cuartielles Examiner: Susan Kozel Thesis defense: 31 May 2012 | 10:00-11:00 at MEDEA research center for collaborative media More info at: vincentolislagers.com This text and the design work in it are available under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported License p. 2 ABSTRACT ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This thesis begins with a philosophical question: What if we I would like to express my gratitude to everyone who has shared could amplify our waking experience with the aesthetic qualities their intelligence and offered me their assistance of dreams? Through a discourse on experiential dream related during the thesis writing and my Master studies, I am truly aspects in philosophy, design and daily life it examines what it indebted to you. In particular I am thankful to: means, and has meant, to dream, and how these qualities already permeate the physical world. I hypothesize that objects capable of Hans & Monique Olislagers for allowing me to realize my dreams representing dream related physiological data as physical output and for their unwavering support. My supervising professor have the potential to amplify our waking experience. To formulate a David Cuartielles for his guidance, and for creating the Arduino set of considerations for the design of such objects, an ethnographic prototyping platform, which has enabled me to test my ideas with study of dream experience, comprising a survey, a cultural probe real people. -

Jade Huang and Chinese Culture Identity: Focus on the Myth of “Huang of Xiahoushi”

Journal of Literature and Art Studies, June 2016, Vol. 6, No. 6, 603-618 doi: 10.17265/2159-5836/2016.06.003 D DAVID PUBLISHING Jade Huang and Chinese Culture Identity: Focus on the Myth of “Huang of Xiahoushi” TANG Qi-cui, WU Yu-wei Shanghai Jiao Tong University, Shanghai, China This paper focus on the myth of “Huang of Xiahoushi” (夏后氏之璜), focusing on the distribution of Jade Huang (玉璜) since the early neolithic and its process of pluralistic integration. The paper explores the story of ethnic group, cultural identification and the significance of Jade Huang in the discourse construction of etiquette civilization behind the mythic narrative based on multi-evidence method and the local meaning of literature in ancient Chinese context. Keywords: Jade Huang, Huang of Xiahoushi, unified diversity, Chinese identity, etiquette civilization, multi-evidence method Introduction Modern archeological relics including potteries, jades and bronzes bring back the lost history; the process of how Chinese unified diversity took shape in general and the great tradition of jade culture in eight thousand in particular. The handed-down documents echo each other at a distance provide solid evidences for the origin of civilization of rite and music and the core values based on jade belief. Jade Huang is an important one of it. It is illuminated by numerous records about Jade Huang in ancient literature, as well as a large number of archaeology findings past 7,000 years. The paper seeks to focus on the following questions: what is the function of Jade Huang in historic and prehistoric period? Moreover, what is the function of “Huang of Xiahoushi”, which belonged to emperor and symbolized special power in historic documents and myths and legends in ancient china? Jade Huang: Etiquette and Literature Jade Huang (Yu Huang, Semi-circular/annular Jade Pendant) is a type of jade artifact which is seemed to be remotely related to etiquette and literature. -

Spring 2020 Syllabus

PSY 353 Sleep! Seminar Spring 2020 SLEEP! Class Times: T 4:40-7:00pm in RKC 200 | Office Hours: M 1:30-2:30pm/W 9:30-10:30am/by appointment Instructor Dr. Justin Hulbert office: Preston 108 phone: x4390 e-mail: [email protected] (preferred contact) Course Materials Materials will be posted on Moodle (see footer for URL & access code). Prerequisites This course is open to Course Overview moderated students who have People spend roughly one-third of their lives asleep. All too many completed at least one of the spend the rest of their lives chronically underslept. What are the following prerequisites: pressures that drive us to sleep? What are the benefits of sleep and Cognitive Psychology (PSY the risks of not sleeping enough? In this upper-level seminar, we 234), Learning & Memory (PSY 243), Neuroscience (PSY 231), will attempt to answer such questions by reviewing the empirical Introduction to Neurobiology literature and designing studies to better understand how we can (BIO 162), or have the get the most out of sleep instructor’s permission. Assessment Joint Responsibilities Achieving the broad aims of this course requires commitments • Participation: 35% from instructor and students alike. Below you will find an outline of • Sleep camp report: 5% some of those responsibilities. • Sleep scoring eval.: 5% • Article presentation: 15% • Your instructor agrees to… • Grant proposal: 40% a) Make himself available outside of class during • Extra credit: up to +2% pts. posted office hours (and by appointment, as necessary) to answer questions, provide extra help, and discuss matters related to the course of study. -

Mongolo-Tibetica Pragensia 12-2.Indd

Mongolo-Tibetica Pragensia ’12 5/2 MMongolo-Tibeticaongolo-Tibetica PPragensiaragensia 112-2.indd2-2.indd 1 115.5. 22.. 22013013 119:13:299:13:29 MMongolo-Tibeticaongolo-Tibetica PPragensiaragensia 112-2.indd2-2.indd 2 115.5. 22.. 22013013 119:13:299:13:29 Mongolo-Tibetica Pragensia ’12 Ethnolinguistics, Sociolinguistics, Religion and Culture Volume 5, No. 2 Publication of Charles University in Prague Philosophical Faculty, Institute of South and Central Asia Seminar of Mongolian Studies Prague 2012 ISSN 1803–5647 MMongolo-Tibeticaongolo-Tibetica PPragensiaragensia 112-2.indd2-2.indd 3 115.5. 22.. 22013013 119:13:299:13:29 Th is journal is published as a part of the Programme for the Development of Fields of Study at Charles University, Oriental and African Studies, sub-programme “Th e process of transformation in the language and cultural diff erentness of the countries of South and Central Asia”, a project of the Philosophical Faculty, Charles University in Prague. Mongolo-Tibetica Pragensia ’12 Linguistics, Ethnolinguistics, Religion and Culture Volume 5, No. 2 (2012) © Editors Editors-in-chief: Jaroslav Vacek and Alena Oberfalzerová Editorial Board: Daniel Berounský (Charles University in Prague, Czech Republic) Agata Bareja-Starzyńska (University of Warsaw, Poland) Katia Buff etrille (École pratique des Hautes-Études, Paris, France) J. Lubsangdorji (Charles University Prague, Czech Republic) Marie-Dominique Even (Centre National des Recherches Scientifi ques, Paris, France) Marek Mejor (University of Warsaw, Poland) Tsevel Shagdarsurung (National University of Mongolia, Ulaanbaatar, Mongolia) Domiin Tömörtogoo (National University of Mongolia, Ulaanbaatar, Mongolia) Reviewed by Prof. Václav Blažek (Masaryk University, Brno, Czech Republic) and Prof. Tsevel Shagdarsurung (National University of Mongolia, Ulaanbaatar, Mongolia) English correction: Dr. -

Download E-Book (PDF)

Journal of Languages and Culture Volume 8 Number 3 March 2017 ISSN 2141-6540 ABOUT JLC The Journal of Languages and Culture (JLC) will be published monthly (one volume per year) by Academic Journals. Journal of Languages and Culture (JLC) is an open access journal that provides rapid publication (monthly) of articles in all areas of the subject such as Political Anthropology, Culture Change, Chinese Painting, Comparative Study of Race, Literary Criticism etc. Contact Us Editorial Office: [email protected] Help Desk: [email protected] Website: http://www.academicjournals.org/journal/JLC Submit manuscript online http://ms.academicjournals.me/ Editors Dr. Marta Manrique Gómez Prof. Ahmed Awad Amin Mahmoud Faculty of Education and Higher Education Middlebury College An-Najah National University, Department of Spanish and Portuguese Nablus. Warner Hall, H-15 Palestine. Middlebury, VT 05753 USA. Dr. R. Joseph Ponniah Dr. Yanjiang Teng Department of Humanities (English) 801 Cherry Lane, APT201 National Institute of Technology Trichirappalli, Tamil Nadu East Lansing India. Michigan State University MI 48824 Dr. Kanwar Dinesh Singh USA. # 3, Cecil Quarters, Chaura Maidan, Shimla:171004 HP Prof. Radhakrishnan Nair India. SCMS-COCHIN Address Prathap Nagar, Muttom, Aluva-1 India. Dr. S. D. Sindkhedkar Head, Department of English, PSGVP Mandal's Arts, Science & Commerce College, Prof. Lianrui Yang Shahada: 425409, (Dist. Nandurbar), (M.S.), School of Foreign Languages, Ocean University of India. China Address 23 Hongkong East Road, Qingdao, Shandong Province, 266071 P China. Editorial Board Dr. Angeliki Koukoutsaki-Monnier Benson Oduor Ojwang University of Haute Alsace Maseno University IUT de Mulhouse P.O.BOX 333, MASENO 40105 Kenya.