Dogma, Romance and Double Consciousness

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

When Fear Is Substituted for Reason: European and Western Government Policies Regarding National Security 1789-1919

WHEN FEAR IS SUBSTITUTED FOR REASON: EUROPEAN AND WESTERN GOVERNMENT POLICIES REGARDING NATIONAL SECURITY 1789-1919 Norma Lisa Flores A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY December 2012 Committee: Dr. Beth Griech-Polelle, Advisor Dr. Mark Simon Graduate Faculty Representative Dr. Michael Brooks Dr. Geoff Howes Dr. Michael Jakobson © 2012 Norma Lisa Flores All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT Dr. Beth Griech-Polelle, Advisor Although the twentieth century is perceived as the era of international wars and revolutions, the basis of these proceedings are actually rooted in the events of the nineteenth century. When anything that challenged the authority of the state – concepts based on enlightenment, immigration, or socialism – were deemed to be a threat to the status quo and immediately eliminated by way of legal restrictions. Once the façade of the Old World was completely severed following the Great War, nations in Europe and throughout the West started to revive various nineteenth century laws in an attempt to suppress the outbreak of radicalism that preceded the 1919 revolutions. What this dissertation offers is an extended understanding of how nineteenth century government policies toward radicalism fostered an environment of increased national security during Germany’s 1919 Spartacist Uprising and the 1919/1920 Palmer Raids in the United States. Using the French Revolution as a starting point, this study allows the reader the opportunity to put events like the 1848 revolutions, the rise of the First and Second Internationals, political fallouts, nineteenth century imperialism, nativism, Social Darwinism, and movements for self-government into a broader historical context. -

Claude Mckay's a Long Way from Home

Through a Black Traveler's Eyes: Claude McKay's A Long Way from Home Tuire Valkeakari Yale University Abstract: This essay analyzes Jamaican-born Claude McKay's discussion of racism(s) and nationalism(~) in his travelogue/autobiography A Long Way from Home ( 1937), in which he chronicles his sojourn in Europe and North Africa and addresses his complex relationship to the United States. Much of McKay's social analysis draws, as this essay establishes, on his observation that racism and nationalism tend to be intertwined and feed 011 each othe1: While describing his travels, McKay presents himselfas a bordercrosser who is "a bad nationalist" and an "internationalist" - a cosmopolitan whose home cannot be defined by any fixed national labels or by nationalist or racialist identity politics. This essay's dialogue with McKay's memoir ultimately reconstructs his difficult and of1-frustrated quest for democracy - the political condition that Ralph Ellison once eloquently equated with "man~· being at home in. the world." Key words: Claude McKay - nationalism - transnationalism - cosmopolitanism - race - racism - travel The way home we seek is that condition of man's being at home in the world, which is called love, and which we tenn democracy. - Ralph Elli son, "Brave Words for a Startling Occasion" I said I was born in the West Indies and lived in the United States and that I was an American, even though I was a British subject, but 1 preferred to think of myself as an internationalist. The chaoL1Sh said he didn't understand what was an internationalist. J laughed and said that an internationalist was a bad nationalist. -

Sylvia Pankhurst's Sedition of 1920

“Upheld by Force” Sylvia Pankhurst’s Sedition of 1920 Edward Crouse Undergraduate Thesis Department of History Columbia University April 4, 2018 Seminar Advisor: Elizabeth Blackmar Second Reader: Susan Pedersen With dim lights and tangled circumstance they tried to shape their thought and deed in noble agreement; but after all, to common eyes their struggles seemed mere inconsistency and formlessness; for these later-born Theresas were helped by no coherent social faith and order which could perform the function of knowledge for the ardently willing soul. Their ardor alternated between a vague ideal and the common yearning of womanhood; so that the one was disapproved as extravagance, and the other condemned as a lapse. – George Eliot, Middlemarch, 1872 Table of Contents Acknowledgements ................................................................................................................... 2 Abbreviations ............................................................................................................................ 3 Introduction .............................................................................................................................. 4 The End of Edwardian England: Pankhurst’s Political Development ................................. 12 After the War: Pankhurst’s Collisions with Communism and the State .............................. 21 Appealing Sedition: Performativity of Communism and Suffrage ....................................... 33 Prison and Release: Attempted Constructions of Martyrology -

D. H. Lawrence and the Harlem Renaissance

‘You are white – yet a part of me’: D. H. Lawrence and the Harlem Renaissance A thesis submitted to The University of Manchester for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Faculty of Humanities 2019 Laura E. Ryan School of Arts, Languages and Cultures 2 Contents Abstract ...................................................................................................................... 3 Declaration ................................................................................................................. 4 Copyright statement ................................................................................................... 5 Acknowledgements .................................................................................................... 6 Introduction ................................................................................................................ 7 Chapter 1: ‘[G]roping for a way out’: Claude McKay ................................................ 55 Chapter 2: Chaos in Short Fiction: Langston Hughes ............................................ 116 Chapter 3: The Broken Circle: Jean Toomer .......................................................... 171 Chapter 4: ‘Becoming [the superwoman] you are’: Zora Neale Hurston................. 223 Conclusion ............................................................................................................. 267 Bibliography ........................................................................................................... 271 Word Count: 79940 3 -

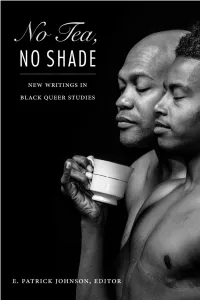

NO TEA, NO SHADE This Page Intentionally Left Blank No Tea, NO SHADE

NO TEA, NO SHADE This page intentionally left blank No Tea, NO SHADE New Writings in Black Queer Studies EDITED BY E. Patrick Johnson duke university press Durham & London 2016 © 2016 Duke University Press All rights reserved Printed in the United States of Amer i ca on acid- free paper ∞ Typeset in Adobe Caslon by Westchester Publishing Services Library of Congress Cataloging- in- Publication Data Names: Johnson, E. Patrick, [date] editor. Title: No tea, no shade : new writings in Black queer studies / edited by E. Patrick Johnson. Description: Durham : Duke University Press, 2016. | Includes bibliographical references and index. Identifiers: lccn 2016022047 (print) lccn 2016023801 (ebook) isbn 9780822362227 (hardcover : alk. paper) isbn 9780822362425 (pbk. : alk. paper) isbn 9780822373711 (e- book) Subjects: lcsh: African American gays. | Gay and lesbian studies. | African Americans in popu lar culture. | Gays in popu lar culture. | Gender identity— Political aspects. | Sex in popu lar culture. Classification: lcc e185.625.n59 2016 (print) | lcc e185.625 (ebook) | ddc 306.76/608996073— dc23 lc rec ord available at https:// lccn . loc . gov / 2016022047 Cover art: Philip P. Thomas, Sharing Tea, 2016. © Philip P. Thomas. FOR ALL THE QUEER FOREMOTHERS AND FOREFATHERS This page intentionally left blank CONTENTS foreword Cathy J. Cohen xi acknowl edgments xv introduction E. Patrick Johnson 1 CHAPTER 1. Black/Queer Rhizomatics Train Up a Child in the Way Ze Should Grow . JAFARI S. ALLEN 27 CHAPTER 2. The Whiter the Bread, the Quicker You’re Dead Spectacular Absence and Post-Racialized Blackness in (White) Queer Theory ALISON REED 48 CHAPTER 3. Troubling the Waters Mobilizing a Trans* Analytic KAI M. -

German Communists

= ~•••••••••• B•••••••~•••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••• a• •= :• COMING PUBLICATIONS: •= =• / ~ • .= "ABOUT BELGIUM" by Camille Huysrnans. ; "THE FLAMING BORDER" by Czeslaw Poznanski. "GERMAN CONSERVATIVES" by Curt Geyer. "THE ROAD TO MUNICH" by Dr. Jan Opocenski. "THE WOLF AS A NEIGHBOUR" by M. van Blankenstein. NEW SERIES: THE FUTURE OF EUROPE AND THE WO~LD "GERMANY AT PEACE" by Walter Loeb. "FRENCH SECURITY AND GERMANY" . by Edmond Vermeil. "PROGRESS TO WORLD PEACE" by K. F. Bieligk. - HUTCHINSON & CO. (Publishers), LTD. ••••m•••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••2. "FIGHT FOR FREEDOM" Editorial Board LUIS ARAQUISTAIN CAM!LLE HUYSMANS JOSEF BELINA PROFESSOR A. PRAGIER JOHN BROWN M. SLUYSER CURT GEYER RENNIE SMITH W . W. HENDERSON MARY E. SUTHERLAND,7 j.P. GERMAN COMMUNISTS by ./ SPARTAKUS Foreword by ALFRED M. WALL Translated from the German by. E. Fitzgerald TO THE MEMORY OF ROSA LUXEMBURG KARL LIEBKNECHT PAUL- LEVI - SPARTAKUS has lived in Germany all. his life andIeft shortly after Hitler came.,.10 power. ' From his youth he has worked in the German Labour Movements-Socialist and Communist. He was one of the early "Spartakists" in the last war and he is still . today . a devoted fighter against German aggression and 'nationalism from whatever source it may spring. CONTENTS PAGE . FOREWORD 4 PART l THE SPARTACUS LEAGUE 1914-1918 7 PART II THE COMMUNIST PARTY 1919-1933 22 THE PARTY AND THE VERSAILLES TREATY 22 THE KAPP "PUTSCH" 28 THE UNITED COMMUNIST PARTY OF GERMANY 30 THE W..ARCH ACTION . 34 THE NATIONALISTIC LINE . ..... .. ' 36 THE RAPALLO TREATY' 38 THE OCCUPATION OF THE RUHR 39 SCHLAGETER 42 CORRUPTION 45 THE UNSUCCESSFUL RISING OF 1923 46 THE DECLINE OF THE GERMAN COMMUNIST PARTY 48 GERMAN MILITARY EXPENDITURE 53 "THE HORNY-HANDED SON OF TOIL". -

Cpdoc Programa De Pós-Graduação Em História, Política E Bens Culturais Mestrado Acadêmico Em História, Política E Bens Culturais

FUNDAÇÃO GETÚLIO VARGAS CENTRO DE PESQUISA E DOCUMENTAÇÃO DE HISTÓRIA CONTEMPORÂNEA DO BRASIL – CPDOC PROGRAMA DE PÓS-GRADUAÇÃO EM HISTÓRIA, POLÍTICA E BENS CULTURAIS MESTRADO ACADÊMICO EM HISTÓRIA, POLÍTICA E BENS CULTURAIS Lucas Andrade Sá Corrêa Um nome e um programa: Érico Sachs e a Política Operária Rio de Janeiro, 2014 FUNDAÇÃO GETÚLIO VARGAS CENTRO DE PESQUISA E DOCUMENTAÇÃO DE HISTÓRIA CONTEMPORÂNEA DO BRASIL – CPDOC PROGRAMA DE PÓS-GRADUAÇÃO EM HISTÓRIA, POLÍTICA E BENS CULTURAIS MESTRADO ACADÊMICO EM HISTÓRIA, POLÍTICA E BENS CULTURAIS Lucas Andrade Sá Corrêa Um nome e um programa: Érico Sachs e a Política Operária Dissertação apresentada ao Programa de Pós Graduação em História, Política e Bens Culturais do Centro de Pesquisa e Documentação de História Contemporânea do Brasil (PPGHPBC-CPDOC) como Requisito para a obtenção do título de Mestre. Orientadora: Profa. Dra. Dulce Chaves Pandolfi Rio de Janeiro, 2014 Ficha catalográfica elaborada pela Biblioteca Mario Henrique Simonsen/FGV Corrêa, Lucas Andrade Sá Um nome e um programa : Érico Sachs e a Política Operária / Lucas Andrade Sá Corrêa. – 2014. 126 f. Dissertação (mestrado) – Centro de Pesquisa e Documentação de História Contemporânea do Brasil, Programa de Pós-Graduação em História Política e Bens Culturais. Orientadora: Dulce Chaves Pandolfi. Inclui bibliografia. 1. Organização Revolucionária Marxista – Política Operária. 2. Comunismo. 3. Socialismo. 4. Sachs, Érico Czaczkes, 1922-1986. 5. Lukács, György, 1885-1971. I. Pandolfi, Dulce Chaves. II. Centro de Pesquisa e Documentação de História Contemporânea do Brasil. Programa de Pós-Graduação em História Política e Bens Culturais. III.Título. CDD – 320.5315 Resumo: CORRÊA, Lucas Andrade Sá. Um nome e um programa: Érico Sachs e a Política Operária. -

Theodore Draper Papers, 1912-1966

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/tf0z09n45f No online items Preliminary Inventory to the Theodore Draper Papers, 1912-1966 Processed by ; machine-readable finding aid created by Xiuzhi Zhou Hoover Institution Archives Stanford University Stanford, California 94305-6010 Phone: (650) 723-3563 Fax: (650) 725-3445 Email: [email protected] © 1998 Hoover Institution Archives. All rights reserved. Preliminary Inventory to the 67001 1 Theodore Draper Papers, 1912-1966 Preliminary Inventory to the Theodore Draper Papers, 1912-1966 Hoover Institution Archives Stanford University Stanford, California Contact Information Hoover Institution Archives Stanford University Stanford, California 94305-6010 Phone: (650) 723-3563 Fax: (650) 725-3445 Email: [email protected] Encoded by: Xiuzhi Zhou © 1998 Hoover Institution Archives. All rights reserved. Descriptive Summary Title: Theodore Draper Papers, Date (inclusive): 1912-1966 Collection number: 67001 Creator: Draper, Theodore, 1912- Collection Size: 37 manuscript boxes, 1 phonotape reel(15.5 linear feet) Repository: Hoover Institution Archives Stanford, California 94305-6010 Abstract: Correspondence, clippings, pamphlets, newspaper issues, and congressional hearings, relating to the revolution led by Fidel Castro in Cuba, political, social, and economic conditions in Cuba, the 1965 crisis and American intervention in the Dominican Republic, and the Communist Party of the United States. Physical Location: Hoover Institution Archives Language: English. Access Collection open for research. The Hoover Institution Archives only allows access to copies of audiovisual items. To listen to sound recordings or to view videos or films during your visit, please contact the Archives at least two working days before your arrival. We will then advise you of the accessibility of the material you wish to see or hear. -

The Beginning of the End: the Political Theory of the Gernian Conmunist Party to the Third Period

THE BEGINNING OF THE END: THE POLITICAL THEORY OF THE GERNIAN CONMUNIST PARTY TO THE THIRD PERIOD By Lea Haro Thesis submitted for degree of PhD Centre for Socialist Theory and Movements Faculty of Law, Business, and Social Science January 2007 Table of Contents Abstract I Acknowledgments iv Methodology i. Why Bother with Marxist Theory? I ii. Outline 5 iii. Sources 9 1. Introduction - The Origins of German Communism: A 14 Historical Narrative of the German Social Democratic Party a. The Gotha Unity 15 b. From the Erjlurt Programme to Bureaucracy 23 c. From War Credits to Republic 30 II. The Theoretical Foundations of German Communism - The 39 Theories of Rosa Luxemburg a. Luxemburg as a Theorist 41 b. Rosa Luxemburg's Contribution to the Debates within the 47 SPD i. Revisionism 48 ii. Mass Strike and the Russian Revolution of 1905 58 c. Polemics with Lenin 66 i. National Question 69 ii. Imperialism 75 iii. Political Organisation 80 Summary 84 Ill. Crisis of Theory in the Comintern 87 a. Creating Uniformity in the Comintern 91 i. Role of Correct Theory 93 ii. Centralism and Strict Discipline 99 iii. Consequencesof the Policy of Uniformity for the 108 KPD b. Comintern's Policy of "Bolshevisation" 116 i. Power Struggle in the CPSU 120 ii. Comintern After Lenin 123 iii. Consequencesof Bolshevisation for KPD 130 iv. Legacy of Luxemburgism 140 c. Consequencesof a New Doctrine 143 i. Socialism in One Country 145 ii. Sixth Congress of the Comintern and the 150 Emergence of the Third Period Summary 159 IV. The Third Period and the Development of the Theory of Social 162 Fascism in Germany a. -

THE POLITICAL THOUGHT of the THIRD WORLD LEFT in POST-WAR AMERICA a Dissertation Submitted

LIBERATION FROM THE AFFLUENT SOCIETY: THE POLITICAL THOUGHT OF THE THIRD WORLD LEFT IN POST-WAR AMERICA A Dissertation submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences of Georgetown University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History By Benjamin Feldman, M.A. Washington, DC August 6, 2020 Copyright 2020 by Benjamin Feldman All Rights Reserved ii LIBERATION FROM THE AFFLUENT SOCIETY: THE POLITICAL THOUGHT OF THE THIRD WORLD LEFT IN POST-WAR AMERICA Benjamin Feldman, M.A. Thesis Advisor: Michael Kazin, Ph.D. ABSTRACT This dissertation traces the full intellectual history of the Third World Turn: when theorists and activists in the United States began to look to liberation movements within the colonized and formerly colonized nations of the ‘Third World’ in search of models for political, social, and cultural transformation. I argue that, understood as a critique of the limits of New Deal liberalism rather than just as an offshoot of New Left radicalism, Third Worldism must be placed at the center of the history of the post-war American Left. Rooting the Third World Turn in the work of theorists active in the 1940s, including the economists Paul Sweezy and Paul Baran, the writer Harold Cruse, and the Detroit organizers James and Grace Lee Boggs, my work moves beyond simple binaries of violence vs. non-violence, revolution vs. reform, and utopianism vs. realism, while throwing the political development of groups like the Black Panthers, the Young Lords, the League of Revolutionary Black Workers, and the Third World Women’s Alliance into sharper relief. -

Introduction 1

Notes Introduction 1 . Similar attempts to link poetry to immediate political occasions have been made by Mark van Wienen in Partisans and Poets: The Political Work of American Poetry in the Great War and by John Marsh’s anthology You Work Tomorrow . See also Nancy Berke’s Women Poets on the Left and John Lowney’s History, Memory, and the Literary Left: Modern American Poetry, 1935–1968 . 2 . Jos é E. Lim ó n discusses the “mixture of poetry and politics” that informed the Chicano movements of the 1960s and 1970s (81). On Vietnam antiwar poetry, see Bibby. There are, of course, countless studies of individual authors that trace their relationships to politics and social movements. I incorporate the relevant studies throughout the chapters. 3 . In analogy to Wallerstein’s model, the literary world has been conceptualized as a largely autonomous cultural space constituted by power struggles between centers, semi-peripheries, and peripheries, most prominently by Franco Moretti and Pascale Casanova (cf. Moretti; Casanova). But since Wallerstein insists that the world-system is concerned with world-economies (global capitalism) and world-empires (nation-states aiming for geopolitical dominance), systems, that is, which cut across cultural and institutional zones, it seems more plausible to posit the modern world-system as the historical horizon of textual production and interpretation. One of the first uses of world-systems analysis for a concep- tualization of postmodernity and postmodern art was Fredric Jameson’s essay “Culture and Finance Capital” ( Cultural Turn 136–61). 4 . Ramazani remains elusive about the extraliterary reference of these poets’ imagination. -

The Trade Union Unity League: American Communists and The

LaborHistory, Vol. 42, No. 2, 2001 TheTrade Union Unity League: American Communists and the Transitionto Industrial Unionism:1928± 1934* EDWARDP. JOHANNINGSMEIER The organization knownas the Trade UnionUnity League(TUUL) came intoformal existenceat anAugust 1929 conferenceof Communists and radical unionistsin Cleveland.The TUUL’s purposewas to create and nourish openly Communist-led unionsthat wereto be independent of the American Federation ofLabor in industries suchas mining, textile, steeland auto. When the TUUL was created, a numberof the CommunistParty’ s mostexperienced activists weresuspicious of the sectarian logic inherentin theTUUL’ s program. In Moscow,where the creation ofnew unions had beendebated by theCommunists the previous year, someAmericans— working within their establishedAFL unions—had argued furiously against its creation,loudly ac- cusingits promoters ofneedless schism. The controversyeven emerged openly for a time in theCommunist press in theUnited States. In 1934, after ve years ofaggressive butmostly unproductiveorganizing, theTUUL was formally dissolved.After the Comintern’s formal inauguration ofthe Popular Front in 1935 many ofthe same organizers whohad workedin theobscure and ephemeral TUULunions aided in the organization ofthe enduring industrial unionsof the CIO. 1 Historiansof American labor andradicalism have had difculty detectingany legitimate rationale for thefounding of theTUUL. Its ve years ofexistence during the rst years ofthe Depression have oftenbeen dismissed as an interlude of hopeless sectarianism,