Copyright by Josch Lampe 2021

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

When Fear Is Substituted for Reason: European and Western Government Policies Regarding National Security 1789-1919

WHEN FEAR IS SUBSTITUTED FOR REASON: EUROPEAN AND WESTERN GOVERNMENT POLICIES REGARDING NATIONAL SECURITY 1789-1919 Norma Lisa Flores A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY December 2012 Committee: Dr. Beth Griech-Polelle, Advisor Dr. Mark Simon Graduate Faculty Representative Dr. Michael Brooks Dr. Geoff Howes Dr. Michael Jakobson © 2012 Norma Lisa Flores All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT Dr. Beth Griech-Polelle, Advisor Although the twentieth century is perceived as the era of international wars and revolutions, the basis of these proceedings are actually rooted in the events of the nineteenth century. When anything that challenged the authority of the state – concepts based on enlightenment, immigration, or socialism – were deemed to be a threat to the status quo and immediately eliminated by way of legal restrictions. Once the façade of the Old World was completely severed following the Great War, nations in Europe and throughout the West started to revive various nineteenth century laws in an attempt to suppress the outbreak of radicalism that preceded the 1919 revolutions. What this dissertation offers is an extended understanding of how nineteenth century government policies toward radicalism fostered an environment of increased national security during Germany’s 1919 Spartacist Uprising and the 1919/1920 Palmer Raids in the United States. Using the French Revolution as a starting point, this study allows the reader the opportunity to put events like the 1848 revolutions, the rise of the First and Second Internationals, political fallouts, nineteenth century imperialism, nativism, Social Darwinism, and movements for self-government into a broader historical context. -

Descrizione Storica Delle Carte (ITA)

PRIMA DECADE I. Russian Tanks (DDR 1953) Nel maggio 1953, il Politburo del Partito di Unita’ Socialista della Germania (SED) innalzo’ le quote di lavoro dell'industria del 10 %. Il 16 giugno, una sessantina di operai edili di Berlino Est iniziarono a scioperare quando i loro superiori annunciarono un taglio di stipendio in caso di mancato raggiungimento delle quote. La loro manifestazione del giorno seguente fu la scintilla che causò lo scoppio delle proteste in tutta la Germania Est. Lo sciopero portò al blocco del lavoro e a proteste in praticamente tutti i centri industriali e in tutte le grandi città del Paese; le richieste iniziali dei dimostranti, come il ripristino delle precedenti (e inferiori) quote di lavoro, si tramutarono in richieste politiche. I lavoratori chiesero le dimissioni del governo della Germania Est che, per contro, si rivolse all'Unione Sovietica per schiacciare la rivolta con la forza militare. 1. Land Reform (DDR 19451945----1948)1948) Le riforme agrarie ("Bodenreform") prevedevano l'espropriazione di tutte le terre appartenenti agli attivisti del nazismo. Circa 500 proprietà degli Junker furono convertite in fattorie collettive, e più di 30.000 km² vennero distribuiti tra mezzo milione di contadini. Inoltre vennero costituite le prime fattorie statali, chiamate Volkseigenes Gut. 2. Forced Merger of KPD and SPD (DDR 1946) Un decreto del 10 giugno 1945 da parte delle autorità sovietiche permise la formazione di partiti democratici antifascisti; le prime elezioni vennero indette a ottobre 1946. Nel luglio 1945 si costituì una coalizione di partiti democratici antifascisti, formata da KPD, SPD, CDU, LDPD. Nell'aprile 1946 il KPD (il partito comunista tedesco e la SPD si fusero dietro grandi pressioni da parte dei sovietici, formando la SED (Sozialistische Einheitspartei Deutschlands, Partito di Unità Socialista). -

Revisiting Zero Hour 1945

REVISITING ZERO-HOUR 1945 THE EMERGENCE OF POSTWAR GERMAN CULTURE edited by STEPHEN BROCKMANN FRANK TROMMLER VOLUME 1 American Institute for Contemporary German Studies The Johns Hopkins University REVISITING ZERO-HOUR 1945 THE EMERGENCE OF POSTWAR GERMAN CULTURE edited by STEPHEN BROCKMANN FRANK TROMMLER HUMANITIES PROGRAM REPORT VOLUME 1 The views expressed in this publication are those of the author(s) alone. They do not necessarily reflect the views of the American Institute for Contemporary German Studies. ©1996 by the American Institute for Contemporary German Studies ISBN 0-941441-15-1 This Humanities Program Volume is made possible by the Harry & Helen Gray Humanities Program. Additional copies are available for $5.00 to cover postage and handling from the American Institute for Contemporary German Studies, Suite 420, 1400 16th Street, N.W., Washington, D.C. 20036-2217. Telephone 202/332-9312, Fax 202/265- 9531, E-mail: [email protected] Web: http://www.aicgs.org ii F O R E W O R D Since its inception, AICGS has incorporated the study of German literature and culture as a part of its mandate to help provide a comprehensive understanding of contemporary Germany. The nature of Germany’s past and present requires nothing less than an interdisciplinary approach to the analysis of German society and culture. Within its research and public affairs programs, the analysis of Germany’s intellectual and cultural traditions and debates has always been central to the Institute’s work. At the time the Berlin Wall was about to fall, the Institute was awarded a major grant from the National Endowment for the Humanities to help create an endowment for its humanities programs. -

The Fumarolic CO Output from Pico Do Fogo Volcano

Ital. J. Geosci., Vol. 139, No. 3 (2020), pp. 325-340, 9 figs., 3 tabs. (https://doi.org/10.3301/IJG.2020.03) © Società Geologica Italiana, Roma 2020 The fumarolic CO2 output from Pico do Fogo Volcano (Cape Verde) ALESSANDRO AIUPPA (1), MARCELLO BITETTO (1), ANDREA L. RIZZO (2), FATIMA VIVEIROS (3), PATRICK ALLARD (4), MARIA LUCE FREZZOTTI (5), VIRGINIA VALENTI (5) & VITTORIO ZANON (3, 4) ABSTRACT output started early back in the 1990s (e.g., GERLACH, 1991), The Pico do Fogo volcano, in the Cape Verde Archipelago off substantial budget refinements have only recently arisen the western coasts of Africa, has been the most active volcano in the from the 8-years (2011-2019) DECADE (Deep Earth Carbon Macaronesia region in the Central Atlantic, with at least 27 eruptions Degassing; https://deepcarboncycle.org/about-decade) during the last 500 years. Between eruptions fumarolic activity has research program of the Deep Carbon Observatory (https:// been persisting in its summit crater, but limited information exists for the chemistry and output of these gas emissions. Here, we use the deepcarbon.net/project/decade#Overview) (FISCHER, 2013; results acquired during a field survey in February 2019 to quantify FISCHER et alii, 2019). the quiescent summit fumaroles’ volatile output for the first time. By One key result of DECADE-funded research has been combining measurements of the fumarole compositions (using both a the recognition that the global CO2 output from subaerial portable Multi-GAS and direct sampling of the hottest fumarole) and volcanism is predominantly sourced from a relatively of the SO2 flux (using near-vent UV Camera recording), we quantify small number of strongly degassing volcanoes. -

Martin Walsers Doppelte Buchführung. Die Konstruktion Und Die Dekonstruktion Der Nationalen Identität in Seinem

Martin Walsers doppelte Buchführung. Die Konstruktion und die Dekonstruktion der nationalen Identität in seinem Spätwerk Inaugural-Dissertation zur Erlangung des akademischen Grades eines Doktors der Philosophie (Dr.phil.) an der Universität Konstanz Fachbereich Literaturwissenschaft Geisteswissenschaftliche Sektion vorgelegt von Jakub Novák Tag der mündlichen Prüfung: 15. Juli 2002 Referent: Prof. Dr. Gerhart von Graevenitz Referentin: Prof. Dr. Almut Todorow Danksagung Ich möchte es nicht versäumen, Herrn Prof. Dr. Gerhart von Graevenitz und Frau Prof. Dr. Almut Todorow für die Unterstützung Dank abzustatten, die sie mir während meines Promotionsstudiums an der Universität Konstanz gewährt haben. Mein herzlicher Dank gebührt des weiteren Dr. Hermann Kinder, mit dem ich einige Aspekte dieser Arbeit erörtern konnte. Bei dem Deutschen Akademischen Austauschdienst (DAAD) in Bonn möchte ich mich bei dieser Gelegenheit für die großzügige finanzielle Förderung bedanken, die die Entstehung dieser Dissertation allererst ermöglicht hat. 2 Ana-Maria gewidmet 3 Inhalt „With Walser the situation is less clear.“ Zum Erkenntnisinteresse dieser Arbeit 6 1. Die Konstruktion und die Dekonstruktion der nationalen Identität in Martin Walsers Essays, Reden und Interviews seit 1977 1. 1. Die ästhetische Konstruktion der personalen Identität 1. 1. 1. Die ästhetische Lebensphilosophie 10 1. 1. 2. Das Schöne, das Wahre, das Gute? 27 1. 1. 3. Zur Topik der Intellektuellenkritik I 32 1. 1. 4. Das Gewissen 37 1. 1. 5. Die Medienkritik 1. 1. 5. 1. Die lebensphilosophische Begründung der Medienkritik 47 1. 1. 5. 2. Die semiotische Begründung der Medienkritik 52 1. 2. Die Nationalisierung der personalen Identität 1. 2. 1. Die ontologisch gegebene Nation 57 1. 2. 2. Zur Topik der Intellektuellenkritik II 64 1. -

From Humiliation to Humanity Reconciling Helen Goldman’S Testimony with the Forensic Strictures of the Frankfurt Auschwitz Trial

S: I. M. O. N. Vol. 8|2021|No.1 SHOAH: INTERVENTION. METHODS. DOCUMENTATION. Andrew Clark Wisely From Humiliation to Humanity Reconciling Helen Goldman’s Testimony with the Forensic Strictures of the Frankfurt Auschwitz Trial Abstract On 3 September 1964, during the Frankfurt Auschwitz trial, Helen Goldman accused SS camp doctor Franz Lucas of selecting her mother and siblings for the gas chamber when the family arrived at Birkenau in May 1944. Although she could identify Lucas, the court con- sidered her information under cross-examination too inconsistent to build a case against Lucas. To appreciate Goldman’s authority, we must remove her from the humiliation of the West German legal gaze and inquire instead how she is seen through the lens of witness hospitality (directly by Emmi Bonhoeffer) and psychiatric assessment (indirectly by Dr Walter von Baeyer). The appearance of Auschwitz survivor Helen (Kaufman) Goldman in the court- room of the Frankfurt Auschwitz trial on 3 September 1964 was hard to forget for all onlookers. Goldman accused the former SS camp doctor Dr Franz Lucas of se- lecting her mother and younger siblings for the gas chamber on the day the family arrived at Birkenau in May 1944.1 Lucas, considered the best behaved of the twenty defendants during the twenty-month-long trial, claimed not to recognise his accus- er, who after identifying him from a line-up became increasingly distraught under cross-examination. Ultimately, the court rejected Goldman’s accusations, choosing instead to believe survivors of Ravensbrück who recounted that Lucas had helped them survive the final months of the war.2 Goldman’s breakdown of credibility echoed the experience of many prosecution witnesses in West German postwar tri- als after 1949. -

Reading References the Eu & the Persian Gulf

Council of the European Union General Secretariat READING REFERENCES 2020 Council Library THE EU & THE PERSIAN GULF Council of the European Union © Picture: Middle East with Countries - Single Color by FreeVectorMaps.com Rue de la Loi/Wetstraat 175 - B-1048 Bruxelles/Brussel - Belgique/België Tel. +32 (0)2 281 65 25 Follow us http://www.consilium.europa.eu/en/library-blog/ - #EUCOlibrary 1/71 Introduction The Persian Gulf has long been a hotspot of geopolitical interest. This year alone has seen sustained media interest in events in the Persian Gulf, including protests, the Iran plane crash and ongoing diplomatic conflicts. To comprehend this vibrant geographical area and its politics, one must gain insight into the region's history, the construction and interconnectedness of its different societies and cultures, the role of religion and the political bodies that exist in the Gulf. As such, the Council Library has compiled this reading list relating to the Persian Gulf. This extensive list has been created both for people who are new to the complex geopolitics of the Persian Gulf, and for those already familiar with the region and its geopolitics. It consists of various books and e-books, articles, podcast episodes, videos and think tank publications, varying from two-minutes' reading, listening or viewing time to more immersive material that can be accessed via the Council Library's online catalogue, Eureka. Resources selected by the Council Libraries Please note: This bibliography is not exhaustive; it provides a selection of resources made by the Council Library. Most of the titles are hyperlinked to Eureka, the resource discovery service of the Council Library, where you can find additional materials on the subject. -

German Ecocriticism an Overview

Citation for published version: Goodbody, A 2014, German ecocriticism: an overview. in G Garrard (ed.), The Oxford Handbook of Ecocriticism. Oxford Handbooks of Literature, Oxford University Press, Oxford, U. K., pp. 547-559. Publication date: 2014 Document Version Early version, also known as pre-print Link to publication University of Bath Alternative formats If you require this document in an alternative format, please contact: [email protected] General rights Copyright and moral rights for the publications made accessible in the public portal are retained by the authors and/or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. Take down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact us providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Download date: 27. Sep. 2021 ‘German Ecocriticism: An Overview’1 Axel Goodbody (for Oxford Handbook of Ecocriticism, ed. Greg Garrard) The contrast between the largely enthusiastic response to ecocriticism in the Anglophone academy and its relative invisibility in the German-speaking world is a puzzle. Why has it yet to gain wider recognition as a field of literary study in Germany, Austria and Switzerland, countries in whose philosophy and cultural tradition nature features so prominently, whose people are shown by international surveys of public opinion to show a high degree of environmental concern, and where environmental issues rank consistently high on the political agenda? One reason may be that German scientists, political thinkers and philosophers have been pioneers in ecology since Humboldt and Haeckel, and non-fiction books have served as the primary medium of public debate on environmental issues in Germany. -

Chapter 6. the Voice of the Other America: African

Chapter 6 Th e Voice of the Other America African-American Music and Political Protest in the German Democratic Republic Michael Rauhut African-American music represents a synthesis of African and European tradi- tions, its origins reaching as far back as the early sixteenth century to the begin- ning of the systematic importation of “black” slaves to the European colonies of the American continent.1 Out of a plethora of forms and styles, three basic pil- lars of African-American music came to prominence during the wave of indus- trialization that took place at the start of the twentieth century: blues, jazz, and gospel. Th ese forms laid the foundation for nearly all important developments in popular music up to the present—whether R&B, soul and funk, house music, or hip-hop. Th anks to its continual innovation and evolution, African-American music has become a constitutive presence in the daily life of several generations. In East Germany, as throughout European countries on both sides of the Iron Curtain, manifold directions and derivatives of these forms took root. Th ey were carried through the airwaves and seeped into cultural niches until, fi nally, this music landed on the political agenda. Both fans and functionaries discovered an enormous social potential beneath the melodious surface, even if their aims were for the most part in opposition. For the government, the implicit rejection of the communist social model represented by African-American music was seen as a security issue and a threat to the stability of the system. Even though the state’s reactions became weaker over time, the offi cial interaction with African-American music retained a political connotation for the life of the regime. -

Alexander Kluge Raw Materials for the Imagination

FILM CULTURE IN TRANSITION Alexander Kluge Raw Materials for the Imagination EDITED BY TARA FORREST Amsterdam University Press Alexander Kluge Alexander Kluge Raw Materials for the Imagination Edited by Tara Forrest Front cover illustration: Alexander Kluge. Photo: Regina Schmeken Back cover illustration: Artists under the Big Top: Perplexed () Cover design: Kok Korpershoek, Amsterdam Lay-out: japes, Amsterdam isbn (paperback) isbn (hardcover) e-isbn nur © T. Forrest / Amsterdam University Press, All rights reserved. Without limiting the rights under copyright reserved above, no part of this book may be reproduced, stored in or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise) without the written permission of both the copyright owner and the author of the book. Every effort has been made to obtain permission to use all copyrighted illustra- tions reproduced in this book. Nonetheless, whosoever believes to have rights to this material is advised to contact the publisher. For Alexander Kluge …and in memory of Miriam Hansen Table of Contents Introduction Editor’s Introduction Tara Forrest The Stubborn Persistence of Alexander Kluge Thomas Elsaesser Film, Politics and the Public Sphere On Film and the Public Sphere Alexander Kluge Cooperative Auteur Cinema and Oppositional Public Sphere: Alexander Kluge’s Contribution to G I A Miriam Hansen ‘What is Different is Good’: Women and Femininity in the Films of Alexander Kluge Heide -

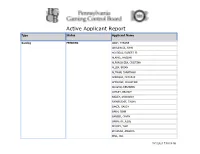

Active Applicant Report Type Status Applicant Name

Active Applicant Report Type Status Applicant Name Gaming PENDING ABAH, TYRONE ABULENCIA, JOHN AGUDELO, ROBERT JR ALAMRI, HASSAN ALFONSO-ZEA, CRISTINA ALLEN, BRIAN ALTMAN, JONATHAN AMBROSE, DEZARAE AMOROSE, CHRISTINE ARROYO, BENJAMIN ASHLEY, BRANDY BAILEY, SHANAKAY BAINBRIDGE, TASHA BAKER, GAUDY BANH, JOHN BARBER, GAVIN BARRETO, JESSE BECKEY, TORI BEHANNA, AMANDA BELL, JILL 10/1/2021 7:00:09 AM Gaming PENDING BENEDICT, FREDRIC BERNSTEIN, KENNETH BIELAK, BETHANY BIRON, WILLIAM BOHANNON, JOSEPH BOLLEN, JUSTIN BORDEWICZ, TIMOTHY BRADDOCK, ALEX BRADLEY, BRANDON BRATETICH, JASON BRATTON, TERENCE BRAUNING, RICK BREEN, MICHELLE BRIGNONI, KARLI BROOKS, KRISTIAN BROWN, LANCE BROZEK, MICHAEL BRUNN, STEVEN BUCHANAN, DARRELL BUCKLEY, FRANCIS BUCKNER, DARLENE BURNHAM, CHAD BUTLER, MALKAI 10/1/2021 7:00:09 AM Gaming PENDING BYRD, AARON CABONILAS, ANGELINA CADE, ROBERT JR CAMPBELL, TAPAENGA CANO, LUIS CARABALLO, EMELISA CARDILLO, THOMAS CARLIN, LUKE CARRILLO OLIVA, GERBERTH CEDENO, ALBERTO CENTAURI, RANDALL CHAPMAN, ERIC CHARLES, PHILIP CHARLTON, MALIK CHOATE, JAMES CHURCH, CHRISTOPHER CLARKE, CLAUDIO CLOWNEY, RAMEAN COLLINS, ARMONI CONKLIN, BARRY CONKLIN, QIANG CONNELL, SHAUN COPELAND, DAVID 10/1/2021 7:00:09 AM Gaming PENDING COPSEY, RAYMOND CORREA, FAUSTINO JR COURSEY, MIAJA COX, ANTHONIE CROMWELL, GRETA CUAJUNO, GABRIEL CULLOM, JOANNA CUTHBERT, JENNIFER CYRIL, TWINKLE DALY, CADEJAH DASILVA, DENNIS DAUBERT, CANDACE DAVIES, JOEL JR DAVILA, KHADIJAH DAVIS, ROBERT DEES, I-QURAN DELPRETE, PAUL DENNIS, BRENDA DEPALMA, ANGELINA DERK, ERIC DEVER, BARBARA -

African Americans, the Civil Rights Movement, and East Germany, 1949-1989

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by eScholarship@BC Friends of Freedom, Allies of Peace: African Americans, the Civil Rights Movement, and East Germany, 1949-1989 Author: Natalia King Rasmussen Persistent link: http://hdl.handle.net/2345/bc-ir:104045 This work is posted on eScholarship@BC, Boston College University Libraries. Boston College Electronic Thesis or Dissertation, 2014 Copyright is held by the author. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Boston College The Graduate School of Arts and Sciences Department of History FRIENDS OF FREEDOM, ALLIES OF PEACE: AFRICAN AMERICANS, THE CIVIL RIGHTS MOVEMENT, AND EAST GERMANY, 1949-1989 A dissertation by NATALIA KING RASMUSSEN submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy December 2014 © copyright by NATALIA DANETTE KING RASMUSSEN 2014 “Friends of Freedom, Allies of Peace: African Americans, the Civil Rights Movement, and East Germany, 1949-1989” Natalia King Rasmussen Dissertation Advisor: Devin O. Pendas This dissertation examines the relationship between Black America and East Germany from 1949 to 1989, exploring the ways in which two unlikely partners used international solidarity to achieve goals of domestic importance. Despite the growing number of works addressing the black experience in and with Imperial Germany, Nazi Germany, West Germany, and contemporary Germany, few studies have devoted attention to the black experience in and with East Germany. In this work, the outline of this transatlantic relationship is defined, detailing who was involved in the friendship, why they were involved, and what they hoped to gain from this alliance.