The Knightian Uncertainty Hypothesis: Unforeseeable Change and Muth’S Consistency Constraint in Modeling Aggregate Outcomes

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Simonian Bounded Rationality Hypothesis and the Expectation Formation Mechanism

Volume 2 Number 1 2002 Tadeusz KOWALSKI The Poznań University of Economics The Simonian bounded rationality hypothesis and the expectation formation mechanism Abstract. In the 1980s and at beginning of the 1990s the debate on expectation forma- tion mechanism was dominated by the rational expectation hypothesis. Later on, more in- terest was directed towards alternative approaches to expectations analysis, mainly based on the bounded rationality paradigm introduced earlier by Herbert A. Simon. The bounded rationality approach is used here to describe the way expectations might be formed by dif- ferent agents. Furthermore, three main hypotheses, namely adaptive, rational and bounded ones are being compared and used to indicate why time lags in economic policy prevail and are variable. Keywords: bounded rationality, substantive and procedural rationality, expectation for- mation, adaptive and rational expectations, time lags. JEL Codes: D78, D84, H30, E00. 1. The theoretical and methodological context The main focus in mainstream economic theories is not as much on the behavior of individual agents as on the outcomes of behaviors and the performance of markets and global institutions. Such theories are based on the classical model of rational choice built on the assumption that agents are aware of all available alternatives and have the ability to assess the outcomes of each possible course of action to be taken, Simon (1982a). Under the standard economic approach, decisions made by agents are always objectively rational. Thus rational agents select scenarios that will serve them best to achieve a specific utility goal. Under this common approach, rationality is an instrumental concept that associates ends and means on the implicit assumption that actions aimed at achieving goals are consistent and effective. -

How the Rational Expectations Revolution Has Enriched

How the Rational Expectations Revolution Has Changed Macroeconomic Policy Research by John B. Taylor STANFORD UNIVERSITY Revised Draft: February 29, 2000 Written versions of lecture presented at the 12th World Congress of the International Economic Association, Buenos Aires, Argentina, August 24, 1999. I am grateful to Jacques Dreze for helpful comments on an earlier draft. The rational expectations hypothesis is by far the most common expectations assumption used in macroeconomic research today. This hypothesis, which simply states that people's expectations are the same as the forecasts of the model being used to describe those people, was first put forth and used in models of competitive product markets by John Muth in the 1960s. But it was not until the early 1970s that Robert Lucas (1972, 1976) incorporated the rational expectations assumption into macroeconomics and showed how to make it operational mathematically. The “rational expectations revolution” is now as old as the Keynesian revolution was when Robert Lucas first brought rational expectations to macroeconomics. This rational expectations revolution has led to many different schools of macroeconomic research. The new classical economics school, the real business cycle school, the new Keynesian economics school, the new political macroeconomics school, and more recently the new neoclassical synthesis (Goodfriend and King (1997)) can all be traced to the introduction of rational expectations into macroeconomics in the early 1970s (see the discussion by Snowden and Vane (1999), pp. 30-50). In this lecture, which is part of the theme on "The Current State of Macroeconomics" at the 12th World Congress of the International Economic Association, I address a question that I am frequently asked by students and by "non-macroeconomist" colleagues, and that I suspect may be on many people's minds. -

Frank Knight 1933-2007 After Receiving His Ph.D

Frank Knight 1933-2007 After receiving his Ph.D. from Princeton University in 1959, Frank Knight joined the mathematics department of the University of Minnesota. Frank liked Minnesota; the cold weather proved to be no difficulty for him since he climbed in the Rocky Mountains even in the winter time. But there was one problem: airborne flour dust, an unpleasant output of the large companies in Minneapolis milling spring wheat from the farms of Minnesota. Frank discovered that he was allergic to flour dust and decided that he would try to move to another location. His research was already recognized as important. His first four papers were published in the Illinois Journal of Mathematics and the Transactions of the American Mathematical Society. At that time, J.L. Doob was one of the editors of the Illinois Journal and attracted some of the best papers in probability theory to the journal including some of Frank's. He was hired by Illinois and served on its faculty from 1963 until his retirement in 1991. After his retirement, Frank continued to be active in his research, perhaps even more active since he no longer had to grade papers and carefully prepare his classroom lectures as he had always done before. In 1994, Frank was diagnosed with Parkinson's disease. For many years, this did not slow him down mathematically. He also kept physically active. At first, his health declined slowly but, in recent years, more rapidly. He died on March 19, 2007. Frank Knight's contributions to probability theory are numerous and often strikingly creative. -

GEORGE J. STIGLER Graduate School of Business, University of Chicago, 1101 East 58Th Street, Chicago, Ill

THE PROCESS AND PROGRESS OF ECONOMICS Nobel Memorial Lecture, 8 December, 1982 by GEORGE J. STIGLER Graduate School of Business, University of Chicago, 1101 East 58th Street, Chicago, Ill. 60637, USA In the work on the economics of information which I began twenty some years ago, I started with an example: how does one find the seller of automobiles who is offering a given model at the lowest price? Does it pay to search more, the more frequently one purchases an automobile, and does it ever pay to search out a large number of potential sellers? The study of the search for trading partners and prices and qualities has now been deepened and widened by the work of scores of skilled economic theorists. I propose on this occasion to address the same kinds of questions to an entirely different market: the market for new ideas in economic science. Most economists enter this market in new ideas, let me emphasize, in order to obtain ideas and methods for the applications they are making of economics to the thousand problems with which they are occupied: these economists are not the suppliers of new ideas but only demanders. Their problem is comparable to that of the automobile buyer: to find a reliable vehicle. Indeed, they usually end up by buying a used, and therefore tested, idea. Those economists who seek to engage in research on the new ideas of the science - to refute or confirm or develop or displace them - are in a sense both buyers and sellers of new ideas. They seek to develop new ideas and persuade the science to accept them, but they also are following clues and promises and explorations in the current or preceding ideas of the science. -

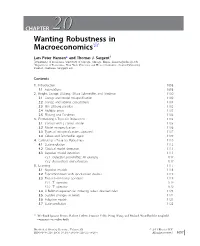

CHAPTER 2020 Wanting Robustness in Macroeconomics$

CHAPTER 2020 Wanting Robustness in Macroeconomics$ Lars Peter Hansen* and Thomas J. Sargent{ * Department of Economics, University of Chicago, Chicago, Illinois. [email protected] { Department of Economics, New York University and Hoover Institution, Stanford University, Stanford, California. [email protected] Contents 1. Introduction 1098 1.1 Foundations 1098 2. Knight, Savage, Ellsberg, Gilboa-Schmeidler, and Friedman 1100 2.1 Savage and model misspecification 1100 2.2 Savage and rational expectations 1101 2.3 The Ellsberg paradox 1102 2.4 Multiple priors 1103 2.5 Ellsberg and Friedman 1104 3. Formalizing a Taste for Robustness 1105 3.1 Control with a correct model 1105 3.2 Model misspecification 1106 3.3 Types of misspecifications captured 1107 3.4 Gilboa and Schmeidler again 1109 4. Calibrating a Taste for Robustness 1110 4.1 State evolution 1112 4.2 Classical model detection 1113 4.3 Bayesian model detection 1113 4.3.1 Detection probabilities: An example 1114 4.3.2 Reservations and extensions 1117 5. Learning 1117 5.1 Bayesian models 1118 5.2 Experimentation with specification doubts 1119 5.3 Two risk-sensitivity operators 1119 5.3.1 T1 operator 1119 5.3.2 T2 operator 1120 5.4 A Bellman equation for inducing robust decision rules 1121 5.5 Sudden changes in beliefs 1122 5.6 Adaptive models 1123 5.7 State prediction 1125 $ We thank Ignacio Presno, Robert Tetlow, Franc¸ois Velde, Neng Wang, and Michael Woodford for insightful comments on earlier drafts. Handbook of Monetary Economics, Volume 3B # 2011 Elsevier B.V. ISSN 0169-7218, DOI: 10.1016/S0169-7218(11)03026-7 All rights reserved. -

ECONOMIC MAN Vs HUMANITY Lyrics

DOUGHNUT ECONOMICS PRESENTS . ECONOMIC MAN vs. HUMANITY: A PUPPET RAP BATTLE STARRING: Storyline and lyrics by Simon Panrucker, Emma Powell and Kate Raworth Key concepts and quotes are drawn from Chapter 3 of Doughnut Economics. * VOICE OVER And so this concept of rational economic man is a cornerstone of economic theory and provides the foundation for modelling the interaction of consumers and firms. The next module will start tomorrow. If you have any questions, please visit your local Knowledge Bank. POTATO Hello? BRASH Hello? FACTS Shall we go to the knowledge bank? BRASH Yeah that didn’t make any sense! POTATO See you outside. They pop up outside. BRASH Let’s go! They go to The Knowledge Bank. PROF Welcome to The Knowledge Ba… oh, it’s you lot. What is it this time? FACTS The model of rational economic man PROF Look, it's just a starting point for building on POTATO Well from the start, something doesn’t sit right with me BRASH We’ve got questions! PROF sighs. PROF Ok, let me go through it again . THE RAP BEGINS PROF Listen, it’s quite simple... At the heart of economics is a model of man A simple distillation of a complicated animal Man is solitary, competing alone, Calculator in head, money in hand and no Relenting, his hunger for more is unending, Ego in heart, nature’s at his will for bending POTATO But that’s not me, it can’t be true! There’s much more to all the things humans say and do! BRASH It’s rubbish! FACTS Well, it is a useful tool For economists to think our reality through It’s said that all models are wrong but some -

Understanding Robert Lucas (1967-1981): His Influence and Influences

A Service of Leibniz-Informationszentrum econstor Wirtschaft Leibniz Information Centre Make Your Publications Visible. zbw for Economics Andrada, Alexandre F.S. Article Understanding Robert Lucas (1967-1981): his influence and influences EconomiA Provided in Cooperation with: The Brazilian Association of Postgraduate Programs in Economics (ANPEC), Rio de Janeiro Suggested Citation: Andrada, Alexandre F.S. (2017) : Understanding Robert Lucas (1967-1981): his influence and influences, EconomiA, ISSN 1517-7580, Elsevier, Amsterdam, Vol. 18, Iss. 2, pp. 212-228, http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.econ.2016.09.001 This Version is available at: http://hdl.handle.net/10419/179646 Standard-Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Die Dokumente auf EconStor dürfen zu eigenen wissenschaftlichen Documents in EconStor may be saved and copied for your Zwecken und zum Privatgebrauch gespeichert und kopiert werden. personal and scholarly purposes. Sie dürfen die Dokumente nicht für öffentliche oder kommerzielle You are not to copy documents for public or commercial Zwecke vervielfältigen, öffentlich ausstellen, öffentlich zugänglich purposes, to exhibit the documents publicly, to make them machen, vertreiben oder anderweitig nutzen. publicly available on the internet, or to distribute or otherwise use the documents in public. Sofern die Verfasser die Dokumente unter Open-Content-Lizenzen (insbesondere CC-Lizenzen) zur Verfügung gestellt haben sollten, If the documents have been made available under an Open gelten abweichend von diesen Nutzungsbedingungen die in der dort Content Licence (especially Creative Commons Licences), you genannten Lizenz gewährten Nutzungsrechte. may exercise further usage rights as specified in the indicated licence. https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/ www.econstor.eu HOSTED BY Available online at www.sciencedirect.com ScienceDirect EconomiA 18 (2017) 212–228 Understanding Robert Lucas (1967-1981): his influence ଝ and influences Alexandre F.S. -

The Wealth Report

THE WEALTH REPORT A GLOBAL PERSPECTIVE ON PRIME PROPERTY AND WEALTH 2011 THE SMALL PRINT TERMS AND DEFINITIONS HNWI is an acronym for ‘high-net-worth individual’, a person whose investible assets, excluding their principal residence, total between $1m and $10m. An UHNWI (ultra-high-net-worth individual) is a person whose investible assets, excluding their primary residence, are valued at over $10m. The term ‘prime property’ equates to the most desirable, and normally most expensive, property in a defined location. Commonly, but not exclusively, prime property markets are areas where demand has a significant international bias. The Wealth Report was written in late 2010 and early 2011. Due to rounding, some percentages may not add up to 100. For research enquiries – Liam Bailey, Knight Frank LLP, 55 Baker Street, London W1U 8AN +44 (0)20 7861 5133 Published on behalf of Knight Frank and Citi Private Bank by Think, The Pall Mall Deposit, 124-128 Barlby Road, London, W10 6BL. THE WEALTH REPORT TEAM FOR KNIGHT FRANK Editor: Andrew Shirley Assistant editor: Vicki Shiel Director of research content: Liam Bailey International data coordinator: Kate Everett-Allen Marketing: Victoria Kinnard, Rebecca Maher Public relations: Rosie Cade FOR CITI PRIVATE BANK Marketing: Pauline Loohuis Public relations: Adam Castellani FOR THINK Consultant editor: Ben Walker Creative director: Ewan Buck Chief sub-editor: James Debens Sub-editor: Jasmine Malone Senior account manager: Kirsty Grant Managing director: Polly Arnold Illustrations: Raymond Biesinger (covers), Peter Field (portraits) Infographics: Leonard Dickinson, Paul Wooton, Mikey Carr Images: 4Corners Images, Getty Images, Bridgeman Art Library PRINTING Ronan Daly at Pureprint Group Limited DISCLAIMERS KNIGHT FRANK The Wealth Report is produced for general interest only; it is not definitive. -

Rational Expectations: Retrospect and Prospect

Rational Expectations: Retrospect and Prospect A Panel Discussion with Michael Lovell Robert Lucas Dale Mortensen Robert Shiller Neil Wallace Moderated by Kevin Hoover Warren Young CHOPE Working Paper No. 2011-10 30 May 2011 Rational Expectations: Retrospect and Prospect A Panel Discussion with Michael Lovell Robert Lucas Dale Mortensen Robert Shiller Neil Wallace Moderated by Kevin Hoover † Warren Young * 30 May 2011 †Department of Economics and Department of Philosophy, Duke University. Address: Box 90097, Durham, NC 27278, U.S.A. E-mail [email protected] *Department of Economics, Bar Ilan University. Address: Department of Economics, Bar Ilan University, Ramat Gan 52900, Israel. E-mail: [email protected] 1 Abstract of Rational Expectations: Retrospect and Prospect The transcript of a panel discussion marking the fiftieth anniversary of John Muth’s “Rational Expectations and the Theory of Price Movements” ( Econometrica 1961). The panel consists of Michael Lovell, Robert Lucas, Dale Mortensen, Robert Shiller, and Neil Wallace. The discussion is moderated by Kevin Hoover and Warren Young. The panel touches on a wide variety of issues related to the rational-expectations hypothesis, including: its history, starting with Muth’s work at Carnegie Tech; its methodological role; applications to policy; its relationship to behavioral economics; its role in the recent financial crisis; and its likely future. JEL Codes: B22, B31, B26, E17 Keywords: rational expectations, John F. Muth, macroeconomics, dynamics, macroeconomic policy, behavioral economics, efficient markets 2 “Rational Expectations” 28 May 2011 Rational Expectations: Retrospect and Prospect: A Panel Discussion with Michael Lovell, Robert Lucas, Dale Mortensen, Robert Shiller and Neil Wallace, Moderated by Kevin Hoover and Warren Young The panel discussion was held in a session sponsored by the History of Economics Society at the Allied Social Sciences Association (ASSA) meetings in the Capitol 1 Room of the Hyatt Regency Hotel in Denver, Colorado on 7 January 2011. -

An Interview with Thomas J. Sargent

Macroeconomic Dynamics, 9, 2005, 561–583. Printed in the United States of America. DOI: 10.1017.S1365100505050042 MD INTERVIEW AN INTERVIEW WITH THOMAS J. SARGENT Interviewed by George W. Evans Department of Economics, University of Oregon and Seppo Honkapohja Faculty of Economics, University of Cambridge January 11, 2005 Keywords: Rational Expectations, Cross-Equation Restrictions, Learning, Model Misspecification, Adaptation, Robustness The rational expectations hypothesis swept through macroeconomics during the 1970s and permanently altered the landscape. It remains the prevailing paradigm in macroeconomics, and rational expectations is routinely used as the stan- dard solution concept in both theoretical and applied macroeconomic mod- elling. The rational expectations hypothesis was initially formulated by John F. Muth Jr. in the early 1960s. Together with Robert Lucas Jr., Thomas (Tom) Sargent pioneered the rational expectations revolution in macroeconomics in the 1970s. Possibly Sargent’s most important work in the early 1970s focused on the implications of rational expectations for empirical and econometric research. His short 1971 paper “A Note on the Accelerationist Controversy” provided a dra- matic illustration of the implications of rational expectations by demonstrating that the standard econometric test of the natural rate hypothesis was invalid. This work was followed in short order by key papers that showed how to conduct valid tests of central macroeconomic relationships under the rational expecta- tions hypothesis. Imposing rational expectations led to new forms of restric- tions, called “cross-equation restrictions,” which in turn required the development of new econometric techniques for the study of macroeconomic relations and models. Correspondence to: Professor George W. Evans, Department of Economics, 1285 University of Oregon, Eugene, OR 97403-1285, USA; e-mail: [email protected]. -

The Midway and Beyond: Recent Work on Economics at Chicago Douglas A

The Midway and Beyond: Recent Work on Economics at Chicago Douglas A. Irwin Since its founding in 1892, the University of Chicago has been home to some of the world’s leading economists.1 Many of its faculty members have been an intellectual force in the economics profession and some have played a prominent role in public policy debates over the past half-cen- tury.2 Because of their impact on the profession and inuence in policy Correspondence may be addressed to: Douglas Irwin, Department of Economics, Dartmouth College, Hanover, NH 03755; email: [email protected]. I am grateful to Dan Ham- mond, Steve Medema, David Mitch, Randy Kroszner, and Roy Weintraub for very helpful com- ments and advice; all errors, interpretations, and misinterpretations are solely my own. Disclo- sure: I was on the faculty of the then Graduate School of Business at the University of Chicago in the 1990s and a visiting professor at the Booth School of Business in the fall of 2017. 1. To take a crude measure, nearly a dozen economists who spent most of their career at Chicago have won the Nobel Prize, or, more accurately, the Sveriges Riksbank Prize in Eco- nomic Sciences in Memory of Alfred Nobel. The list includes Milton Friedman (1976), Theo- dore W. Schultz (1979), George J. Stigler (1982), Merton H. Miller (1990), Ronald H. Coase (1991), Gary S. Becker (1992), Robert W. Fogel (1993), Robert E. Lucas, Jr. (1995), James J. Heckman (2000), Eugene F. Fama and Lars Peter Hansen (2013), and Richard H. Thaler (2017). This list excludes Friedrich Hayek, who did his prize work at the London School of Economics and only spent a dozen years at Chicago. -

Reconsidering Frank Knight As an American Institutionalist

Reconsidering Frank Knight as an American Institutionalist Felipe Almeida Universidade Federal do Paraná Marindia Brites Universidade Federal do Paraná Gustavo Goulart Universidade Federal do Paraná Área 1 - História do Pensamento Econômico e Metodologia Resumo: No início do século XXI, Geoffrey Hodgson apresentou uma controvérsia sobre Frank Knight. Hodgson afirmou que, apesar da falta de apoio historiográfico, Knight foi um institucionalista americano. De acordo com Hodgson, as críticas de Knight à utilidade, preferências dadas, possibilidades tecnológicas fixas e individualismo metodológico seriam suficiente para classificar Knight como um institucionalista. O objetivo desse artigo é investigar a classificação controversa apresebtado por Hodgson. Para tal é realizado um estudo tanto da perspectiva do Knight quanto dos Institucionalistas sobre utilidade, preferências e tecnologia. O artigo conclui que o Knight e o Institutionalismo americano possuem uma conexão ténue, na melhor das hipóteses. Palavras-chave: Frank Knight, Institucionalismo Americano Classificação JEL: B31; B25 Abstract: At the beginning of the 21st century, Geoffrey Hodgson put out a controversial assertion about Frank Knight. He wrote that, despite lack of historiographic support, he saw Knight as an American Institutionalist. He asserted that Knight‘s criticisms of utility, given preferences, fixed technological possibilities, and methodological individualism made him fit into the Institutionalist frame. This paper aims to investigate Hodgson‘s claims, and through