Reconsidering Frank Knight As an American Institutionalist

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Frank Knight 1933-2007 After Receiving His Ph.D

Frank Knight 1933-2007 After receiving his Ph.D. from Princeton University in 1959, Frank Knight joined the mathematics department of the University of Minnesota. Frank liked Minnesota; the cold weather proved to be no difficulty for him since he climbed in the Rocky Mountains even in the winter time. But there was one problem: airborne flour dust, an unpleasant output of the large companies in Minneapolis milling spring wheat from the farms of Minnesota. Frank discovered that he was allergic to flour dust and decided that he would try to move to another location. His research was already recognized as important. His first four papers were published in the Illinois Journal of Mathematics and the Transactions of the American Mathematical Society. At that time, J.L. Doob was one of the editors of the Illinois Journal and attracted some of the best papers in probability theory to the journal including some of Frank's. He was hired by Illinois and served on its faculty from 1963 until his retirement in 1991. After his retirement, Frank continued to be active in his research, perhaps even more active since he no longer had to grade papers and carefully prepare his classroom lectures as he had always done before. In 1994, Frank was diagnosed with Parkinson's disease. For many years, this did not slow him down mathematically. He also kept physically active. At first, his health declined slowly but, in recent years, more rapidly. He died on March 19, 2007. Frank Knight's contributions to probability theory are numerous and often strikingly creative. -

GEORGE J. STIGLER Graduate School of Business, University of Chicago, 1101 East 58Th Street, Chicago, Ill

THE PROCESS AND PROGRESS OF ECONOMICS Nobel Memorial Lecture, 8 December, 1982 by GEORGE J. STIGLER Graduate School of Business, University of Chicago, 1101 East 58th Street, Chicago, Ill. 60637, USA In the work on the economics of information which I began twenty some years ago, I started with an example: how does one find the seller of automobiles who is offering a given model at the lowest price? Does it pay to search more, the more frequently one purchases an automobile, and does it ever pay to search out a large number of potential sellers? The study of the search for trading partners and prices and qualities has now been deepened and widened by the work of scores of skilled economic theorists. I propose on this occasion to address the same kinds of questions to an entirely different market: the market for new ideas in economic science. Most economists enter this market in new ideas, let me emphasize, in order to obtain ideas and methods for the applications they are making of economics to the thousand problems with which they are occupied: these economists are not the suppliers of new ideas but only demanders. Their problem is comparable to that of the automobile buyer: to find a reliable vehicle. Indeed, they usually end up by buying a used, and therefore tested, idea. Those economists who seek to engage in research on the new ideas of the science - to refute or confirm or develop or displace them - are in a sense both buyers and sellers of new ideas. They seek to develop new ideas and persuade the science to accept them, but they also are following clues and promises and explorations in the current or preceding ideas of the science. -

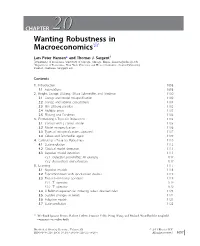

CHAPTER 2020 Wanting Robustness in Macroeconomics$

CHAPTER 2020 Wanting Robustness in Macroeconomics$ Lars Peter Hansen* and Thomas J. Sargent{ * Department of Economics, University of Chicago, Chicago, Illinois. [email protected] { Department of Economics, New York University and Hoover Institution, Stanford University, Stanford, California. [email protected] Contents 1. Introduction 1098 1.1 Foundations 1098 2. Knight, Savage, Ellsberg, Gilboa-Schmeidler, and Friedman 1100 2.1 Savage and model misspecification 1100 2.2 Savage and rational expectations 1101 2.3 The Ellsberg paradox 1102 2.4 Multiple priors 1103 2.5 Ellsberg and Friedman 1104 3. Formalizing a Taste for Robustness 1105 3.1 Control with a correct model 1105 3.2 Model misspecification 1106 3.3 Types of misspecifications captured 1107 3.4 Gilboa and Schmeidler again 1109 4. Calibrating a Taste for Robustness 1110 4.1 State evolution 1112 4.2 Classical model detection 1113 4.3 Bayesian model detection 1113 4.3.1 Detection probabilities: An example 1114 4.3.2 Reservations and extensions 1117 5. Learning 1117 5.1 Bayesian models 1118 5.2 Experimentation with specification doubts 1119 5.3 Two risk-sensitivity operators 1119 5.3.1 T1 operator 1119 5.3.2 T2 operator 1120 5.4 A Bellman equation for inducing robust decision rules 1121 5.5 Sudden changes in beliefs 1122 5.6 Adaptive models 1123 5.7 State prediction 1125 $ We thank Ignacio Presno, Robert Tetlow, Franc¸ois Velde, Neng Wang, and Michael Woodford for insightful comments on earlier drafts. Handbook of Monetary Economics, Volume 3B # 2011 Elsevier B.V. ISSN 0169-7218, DOI: 10.1016/S0169-7218(11)03026-7 All rights reserved. -

ECONOMIC MAN Vs HUMANITY Lyrics

DOUGHNUT ECONOMICS PRESENTS . ECONOMIC MAN vs. HUMANITY: A PUPPET RAP BATTLE STARRING: Storyline and lyrics by Simon Panrucker, Emma Powell and Kate Raworth Key concepts and quotes are drawn from Chapter 3 of Doughnut Economics. * VOICE OVER And so this concept of rational economic man is a cornerstone of economic theory and provides the foundation for modelling the interaction of consumers and firms. The next module will start tomorrow. If you have any questions, please visit your local Knowledge Bank. POTATO Hello? BRASH Hello? FACTS Shall we go to the knowledge bank? BRASH Yeah that didn’t make any sense! POTATO See you outside. They pop up outside. BRASH Let’s go! They go to The Knowledge Bank. PROF Welcome to The Knowledge Ba… oh, it’s you lot. What is it this time? FACTS The model of rational economic man PROF Look, it's just a starting point for building on POTATO Well from the start, something doesn’t sit right with me BRASH We’ve got questions! PROF sighs. PROF Ok, let me go through it again . THE RAP BEGINS PROF Listen, it’s quite simple... At the heart of economics is a model of man A simple distillation of a complicated animal Man is solitary, competing alone, Calculator in head, money in hand and no Relenting, his hunger for more is unending, Ego in heart, nature’s at his will for bending POTATO But that’s not me, it can’t be true! There’s much more to all the things humans say and do! BRASH It’s rubbish! FACTS Well, it is a useful tool For economists to think our reality through It’s said that all models are wrong but some -

Understanding Robert Lucas (1967-1981): His Influence and Influences

A Service of Leibniz-Informationszentrum econstor Wirtschaft Leibniz Information Centre Make Your Publications Visible. zbw for Economics Andrada, Alexandre F.S. Article Understanding Robert Lucas (1967-1981): his influence and influences EconomiA Provided in Cooperation with: The Brazilian Association of Postgraduate Programs in Economics (ANPEC), Rio de Janeiro Suggested Citation: Andrada, Alexandre F.S. (2017) : Understanding Robert Lucas (1967-1981): his influence and influences, EconomiA, ISSN 1517-7580, Elsevier, Amsterdam, Vol. 18, Iss. 2, pp. 212-228, http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.econ.2016.09.001 This Version is available at: http://hdl.handle.net/10419/179646 Standard-Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Die Dokumente auf EconStor dürfen zu eigenen wissenschaftlichen Documents in EconStor may be saved and copied for your Zwecken und zum Privatgebrauch gespeichert und kopiert werden. personal and scholarly purposes. Sie dürfen die Dokumente nicht für öffentliche oder kommerzielle You are not to copy documents for public or commercial Zwecke vervielfältigen, öffentlich ausstellen, öffentlich zugänglich purposes, to exhibit the documents publicly, to make them machen, vertreiben oder anderweitig nutzen. publicly available on the internet, or to distribute or otherwise use the documents in public. Sofern die Verfasser die Dokumente unter Open-Content-Lizenzen (insbesondere CC-Lizenzen) zur Verfügung gestellt haben sollten, If the documents have been made available under an Open gelten abweichend von diesen Nutzungsbedingungen die in der dort Content Licence (especially Creative Commons Licences), you genannten Lizenz gewährten Nutzungsrechte. may exercise further usage rights as specified in the indicated licence. https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/ www.econstor.eu HOSTED BY Available online at www.sciencedirect.com ScienceDirect EconomiA 18 (2017) 212–228 Understanding Robert Lucas (1967-1981): his influence ଝ and influences Alexandre F.S. -

The Wealth Report

THE WEALTH REPORT A GLOBAL PERSPECTIVE ON PRIME PROPERTY AND WEALTH 2011 THE SMALL PRINT TERMS AND DEFINITIONS HNWI is an acronym for ‘high-net-worth individual’, a person whose investible assets, excluding their principal residence, total between $1m and $10m. An UHNWI (ultra-high-net-worth individual) is a person whose investible assets, excluding their primary residence, are valued at over $10m. The term ‘prime property’ equates to the most desirable, and normally most expensive, property in a defined location. Commonly, but not exclusively, prime property markets are areas where demand has a significant international bias. The Wealth Report was written in late 2010 and early 2011. Due to rounding, some percentages may not add up to 100. For research enquiries – Liam Bailey, Knight Frank LLP, 55 Baker Street, London W1U 8AN +44 (0)20 7861 5133 Published on behalf of Knight Frank and Citi Private Bank by Think, The Pall Mall Deposit, 124-128 Barlby Road, London, W10 6BL. THE WEALTH REPORT TEAM FOR KNIGHT FRANK Editor: Andrew Shirley Assistant editor: Vicki Shiel Director of research content: Liam Bailey International data coordinator: Kate Everett-Allen Marketing: Victoria Kinnard, Rebecca Maher Public relations: Rosie Cade FOR CITI PRIVATE BANK Marketing: Pauline Loohuis Public relations: Adam Castellani FOR THINK Consultant editor: Ben Walker Creative director: Ewan Buck Chief sub-editor: James Debens Sub-editor: Jasmine Malone Senior account manager: Kirsty Grant Managing director: Polly Arnold Illustrations: Raymond Biesinger (covers), Peter Field (portraits) Infographics: Leonard Dickinson, Paul Wooton, Mikey Carr Images: 4Corners Images, Getty Images, Bridgeman Art Library PRINTING Ronan Daly at Pureprint Group Limited DISCLAIMERS KNIGHT FRANK The Wealth Report is produced for general interest only; it is not definitive. -

The Midway and Beyond: Recent Work on Economics at Chicago Douglas A

The Midway and Beyond: Recent Work on Economics at Chicago Douglas A. Irwin Since its founding in 1892, the University of Chicago has been home to some of the world’s leading economists.1 Many of its faculty members have been an intellectual force in the economics profession and some have played a prominent role in public policy debates over the past half-cen- tury.2 Because of their impact on the profession and inuence in policy Correspondence may be addressed to: Douglas Irwin, Department of Economics, Dartmouth College, Hanover, NH 03755; email: [email protected]. I am grateful to Dan Ham- mond, Steve Medema, David Mitch, Randy Kroszner, and Roy Weintraub for very helpful com- ments and advice; all errors, interpretations, and misinterpretations are solely my own. Disclo- sure: I was on the faculty of the then Graduate School of Business at the University of Chicago in the 1990s and a visiting professor at the Booth School of Business in the fall of 2017. 1. To take a crude measure, nearly a dozen economists who spent most of their career at Chicago have won the Nobel Prize, or, more accurately, the Sveriges Riksbank Prize in Eco- nomic Sciences in Memory of Alfred Nobel. The list includes Milton Friedman (1976), Theo- dore W. Schultz (1979), George J. Stigler (1982), Merton H. Miller (1990), Ronald H. Coase (1991), Gary S. Becker (1992), Robert W. Fogel (1993), Robert E. Lucas, Jr. (1995), James J. Heckman (2000), Eugene F. Fama and Lars Peter Hansen (2013), and Richard H. Thaler (2017). This list excludes Friedrich Hayek, who did his prize work at the London School of Economics and only spent a dozen years at Chicago. -

Opening Remarks by President James Bullard the 2014 Homer Jones Memorial Lecture Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis April 2, 2014

Opening remarks by President James Bullard The 2014 Homer Jones Memorial Lecture Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis April 2, 2014 Welcome to the Homer Jones Memorial Lecture. This year, we are in a festive mood—and not just because our hometown St. Louis Cardinals are favorites to repeat as National League champions. We’re also in a festive mood because of three other celebrations. First, we are celebrating the 250th anniversary of the city of St. Louis, founded in 1764 by Pierre Laclède and Auguste Chouteau. Second, the Federal Reserve System celebrates its 100th anniversary this year. If you have not done so, I encourage you to visit the Fed’s website at www.federalreservehistory.org to learn more about the nation’s central bank and how it has shaped, and was shaped by, key events in our nation’s economic history. The third cause for celebration is that this year is the 25th annual Homer Jones Memorial Lecture—a quarter century of lectures. The Homer Jones lecture is one of the Bank’s signature events. We hold this lecture each year to honor the lasting contributions of a former Research director of the Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis, Homer Jones. The St. Louis Fed started the lecture series after Homer Jones’ death in 1986. The lecture series enjoys the long-lasting support and co-sponsorship of many people and organizations, including the St. Louis Gateway Chapter of the National Association for Business Economics, Saint Louis University, Southern Illinois University at Edwardsville, the University of Missouri at St. -

Private Notes on Gary Becker

IZA DP No. 8200 Private Notes on Gary Becker James J. Heckman May 2014 DISCUSSION PAPER SERIES Forschungsinstitut zur Zukunft der Arbeit Institute for the Study of Labor Private Notes on Gary Becker James J. Heckman University of Chicago and IZA Discussion Paper No. 8200 May 2014 IZA P.O. Box 7240 53072 Bonn Germany Phone: +49-228-3894-0 Fax: +49-228-3894-180 E-mail: [email protected] Any opinions expressed here are those of the author(s) and not those of IZA. Research published in this series may include views on policy, but the institute itself takes no institutional policy positions. The IZA research network is committed to the IZA Guiding Principles of Research Integrity. The Institute for the Study of Labor (IZA) in Bonn is a local and virtual international research center and a place of communication between science, politics and business. IZA is an independent nonprofit organization supported by Deutsche Post Foundation. The center is associated with the University of Bonn and offers a stimulating research environment through its international network, workshops and conferences, data service, project support, research visits and doctoral program. IZA engages in (i) original and internationally competitive research in all fields of labor economics, (ii) development of policy concepts, and (iii) dissemination of research results and concepts to the interested public. IZA Discussion Papers often represent preliminary work and are circulated to encourage discussion. Citation of such a paper should account for its provisional character. A revised version may be available directly from the author. IZA Discussion Paper No. 8200 May 2014 ABSTRACT Private Notes on Gary Becker* This paper celebrates the life and contributions of Gary Becker (1930-2014). -

Milton Friedman Economist As Public Intellectual

Economic Insights FEDERAL RESERVE BANK OF DALLAS VOLUME 7, NUMBER 2 Milton Friedman Economist as Public Intellectual If asked to name a famous economist, most Americans would probably say Milton Friedman. Economists usually make their contributions behind the scenes at think tanks, gov- ernment agencies or universities. Friedman has done that, but he also has taken his ideas and policy proposals directly to his fellow citizens through books, magazine columns and, especially, television. It is not an exaggeration to say he has been the most influential American economist of the past century. He has changed policy not only here at home but also in many other nations, as much of the world has moved away from economic controls and toward economic freedom. Milton Friedman marks his 90th birthday on July 31, 2002, and the Dallas Fed commem- orates the occasion with this issue of Economic Insights. Happy birthday, Milton! —Bob McTeer Professor Steven N.S. Cheung Professor President, Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas Milton Friedman Milton Friedman has been an ardent introduced the young economist to the uct accounts and many of the tech- and effective advocate for free enter- works of Cambridge School of Eco- niques applied to them in the 1920s prise and monetarist policies for five nomics founder Alfred Marshall. Jones, and ’30s. Because Friedman’s early decades. He was born in Brooklyn, N.Y., a pivotal figure in the monetarist camp, study in economics involved constant in 1912, the son of Jewish immigrants introduced Friedman to Frank Knight contact with theorists such as Burns, who had come to America in the late and the early Chicago school, espe- Mitchell and Kuznets, it is not surpris- 1890s. -

Frank Knight and the Origins of Public Choice

Frank Knight and the Origins of Public Choice David C. Coker George Mason University Ross B. Emmett Professor of Political Economy, School of Civic and Economic Thought and Leadership Director, Center for the Study of Economic Liberty Arizona State University Abstract: Did Frank Knight play a role in the formation of public choice theory? We argue that the dimensions of James Buchanan’s thought that form the core insights of pubic choice become clearer when seen against the work of his teacher, Frank Knight. Buchanan is demonstrative about his indebtedness to Knight; he terms him “my professor” and refers his work frequently. Yet the upfront nature of this acknowledgement has perhaps served to short-circuit analysis as much as to stimulate it. Our analysis will center on Knight’s Intelligence and Democratic Action, a collection of lectures given in 1958 (published 1960), when he was invited by Buchanan to the University of Virginia. The lectures rehearse a number of ideas from other works, yet represent an intriguingly clear connection to ideas Buchanan would present over the coming two decades. In that sense, primarily through his influence on Buchanan, Knight can be seen as one of the largely unacknowledged forefathers of public choice theory. Frank Knight is universally recognized as an interesting and provocative thinker. However, his influence on modern practice has been difficult to pin down. The next generation of theorists at the University of Chicago (Friedman, Stigler, Becker, etc.) seemed to line up in opposition to Knight on many of the questions he considered central (see Emmett 2009b). We will argue that Knight influenced the emergence of public choice theory at the beginning of the 1960s, even though Buchanan did not include Knight as a significant precursor in his Nobel Prize lecture (Buchanan 1986). -

The Psychological Insights of Frank H. Knight

Judgment and Decision Making, Vol. 5, No. 6, October 2010, pp. 458–466 Risk, uncertainty and prophet: The psychological insights of Frank H. Knight Tim Rakow∗ University of Essex Abstract Economist Frank H. Knight (1885–1972) is commonly credited with defining the distinction between decisions under “risk” (known chance) and decisions under “uncertainty” (unmeasurable probability) in his 1921 book Risk, Uncertainty and Profit. A closer reading of Knight (1921) reveals a host of psychological insights beyond this risk-uncertainty distinction, many of which foreshadow revolutionary advances in psychological decision theory from the latter half of the 20th century. Knight’s description of economic decision making shared much with Simon’s (1955, 1956) notion of bounded rationality, whereby choice behavior is regulated by cognitive and environmental constraints. Knight described features of risky choice that were to become key components of prospect theory (Kahneman & Tversky, 1979): the reference dependent valuation of outcomes, and the non-linear weighting of probabilities. Knight also discussed several biases in human decision making, and pointed to two systems of reasoning: one quick, intuitive but error prone, and a slower, more deliberate, rule-based system. A discussion of Knight’s potential contribution to psychological decision theory emphasises the importance of a historical perspective on theory development, and the potential value of sourcing ideas from other disciplines or from earlier periods of time. Keywords: decision making, decision psychology, bounded rationality, prospect theory, Nobel Prize, Herbert Simon, Daniel Kahneman, Amos Tversky, homo economicus. 1 Frank H. Knight — An introduc- nomic theories of decision making by Edwards (1954) tion and embarked upon their own investigations of choice be- havior.