The Psychological Insights of Frank H. Knight

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Choice Procedures Manual

CHOICE SCHOOLS AND PROGRAMS PROCEDURES MANUAL 1. History and Purpose a. The School Board is committed to providing quality educational opportunities for all students. It strives to provide an educational environment that enhances the student’s educational success. The School Board implemented magnet schools and Choice/Career Education programs as one way to ensure that quality educational opportunities were available to all students in diverse settings. The School Board continues to use Choice/Career Education schools and programs as a strategy to provide quality educational opportunities for students in diverse settings, to the extent financial resources are available for the programmatic aspects of these schools and programs and for the related transportation. These educational opportunities will be compliant with federal and state law. b. Choice/Career Education programs are specialized educational programs that enable students to take advantage of additional resources and innovative teaching techniques that focus on the student’s individual talents or interests. Choice schools and programs maintain the mission of: i. improving achievement for all students who are participating in the Choice schools and/or programs; ii. providing a unique or specialized curriculum or approach and maintaining specific goals as stated in the approved Proposal for the Choice Program; iii. promoting and maintaining the educational benefits of a diverse student body; iv. engaging students and providing them with a pathway to post- secondary educational opportunities and career options as outlined in the District’s Strategic Plan. 2. Types of Choice and Career Programs-- At the Pre-K, elementary, middle, and high school levels, the Palm Beach County School District (PBCSD) may implement total-school choice programs or a choice program within a school for zoned or out-of-boundary students. -

Frank Knight 1933-2007 After Receiving His Ph.D

Frank Knight 1933-2007 After receiving his Ph.D. from Princeton University in 1959, Frank Knight joined the mathematics department of the University of Minnesota. Frank liked Minnesota; the cold weather proved to be no difficulty for him since he climbed in the Rocky Mountains even in the winter time. But there was one problem: airborne flour dust, an unpleasant output of the large companies in Minneapolis milling spring wheat from the farms of Minnesota. Frank discovered that he was allergic to flour dust and decided that he would try to move to another location. His research was already recognized as important. His first four papers were published in the Illinois Journal of Mathematics and the Transactions of the American Mathematical Society. At that time, J.L. Doob was one of the editors of the Illinois Journal and attracted some of the best papers in probability theory to the journal including some of Frank's. He was hired by Illinois and served on its faculty from 1963 until his retirement in 1991. After his retirement, Frank continued to be active in his research, perhaps even more active since he no longer had to grade papers and carefully prepare his classroom lectures as he had always done before. In 1994, Frank was diagnosed with Parkinson's disease. For many years, this did not slow him down mathematically. He also kept physically active. At first, his health declined slowly but, in recent years, more rapidly. He died on March 19, 2007. Frank Knight's contributions to probability theory are numerous and often strikingly creative. -

GEORGE J. STIGLER Graduate School of Business, University of Chicago, 1101 East 58Th Street, Chicago, Ill

THE PROCESS AND PROGRESS OF ECONOMICS Nobel Memorial Lecture, 8 December, 1982 by GEORGE J. STIGLER Graduate School of Business, University of Chicago, 1101 East 58th Street, Chicago, Ill. 60637, USA In the work on the economics of information which I began twenty some years ago, I started with an example: how does one find the seller of automobiles who is offering a given model at the lowest price? Does it pay to search more, the more frequently one purchases an automobile, and does it ever pay to search out a large number of potential sellers? The study of the search for trading partners and prices and qualities has now been deepened and widened by the work of scores of skilled economic theorists. I propose on this occasion to address the same kinds of questions to an entirely different market: the market for new ideas in economic science. Most economists enter this market in new ideas, let me emphasize, in order to obtain ideas and methods for the applications they are making of economics to the thousand problems with which they are occupied: these economists are not the suppliers of new ideas but only demanders. Their problem is comparable to that of the automobile buyer: to find a reliable vehicle. Indeed, they usually end up by buying a used, and therefore tested, idea. Those economists who seek to engage in research on the new ideas of the science - to refute or confirm or develop or displace them - are in a sense both buyers and sellers of new ideas. They seek to develop new ideas and persuade the science to accept them, but they also are following clues and promises and explorations in the current or preceding ideas of the science. -

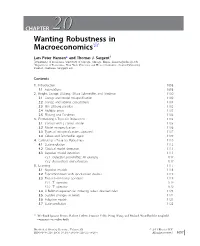

CHAPTER 2020 Wanting Robustness in Macroeconomics$

CHAPTER 2020 Wanting Robustness in Macroeconomics$ Lars Peter Hansen* and Thomas J. Sargent{ * Department of Economics, University of Chicago, Chicago, Illinois. [email protected] { Department of Economics, New York University and Hoover Institution, Stanford University, Stanford, California. [email protected] Contents 1. Introduction 1098 1.1 Foundations 1098 2. Knight, Savage, Ellsberg, Gilboa-Schmeidler, and Friedman 1100 2.1 Savage and model misspecification 1100 2.2 Savage and rational expectations 1101 2.3 The Ellsberg paradox 1102 2.4 Multiple priors 1103 2.5 Ellsberg and Friedman 1104 3. Formalizing a Taste for Robustness 1105 3.1 Control with a correct model 1105 3.2 Model misspecification 1106 3.3 Types of misspecifications captured 1107 3.4 Gilboa and Schmeidler again 1109 4. Calibrating a Taste for Robustness 1110 4.1 State evolution 1112 4.2 Classical model detection 1113 4.3 Bayesian model detection 1113 4.3.1 Detection probabilities: An example 1114 4.3.2 Reservations and extensions 1117 5. Learning 1117 5.1 Bayesian models 1118 5.2 Experimentation with specification doubts 1119 5.3 Two risk-sensitivity operators 1119 5.3.1 T1 operator 1119 5.3.2 T2 operator 1120 5.4 A Bellman equation for inducing robust decision rules 1121 5.5 Sudden changes in beliefs 1122 5.6 Adaptive models 1123 5.7 State prediction 1125 $ We thank Ignacio Presno, Robert Tetlow, Franc¸ois Velde, Neng Wang, and Michael Woodford for insightful comments on earlier drafts. Handbook of Monetary Economics, Volume 3B # 2011 Elsevier B.V. ISSN 0169-7218, DOI: 10.1016/S0169-7218(11)03026-7 All rights reserved. -

Download a Transcript of the Episode

Scene on Radio Freedom Summer (Season 4, Episode 7) Transcript http://www.sceneonradio.org/s4-e7-freedom-summer/ John Biewen: A content warning: this episode includes descriptions of intense violence, and the use of a racial slur. Chenjerai Kumanyika: So John, when you look at history the way that we’re looking at it in this series, sometimes I start to get tempted to make really sloppy historical comparisons. You know what I mean? ‘Cause that’s easy to do. John Biewen: It is easy to do. What’s that expression: history doesn’t repeat itself, but it does often rhyme. And it’s easy to get carried away trying to hear those rhymes. Chenjerai Kumanyika: In the scholarly world, we learn to have nuance and not to do that, but, you know, sometimes, I myself have been guilty. I worked on this podcast, Uncivil, about the Civil War, and during that time I was like, everything is just like 1861. I would be at dinner parties and people are like Chenj, we get it, to 1 understand anything, like a movie–we have to go back to the 19th century, we understand. John Biewen: Yeah. Or, you know, the United States today is Germany 1933! Right? Well, maybe it is, somedays it seems to be, but yeah, you try not to get too carried away reading the newspaper every morning. Chenjerai Kumanyika: Absolutely. That said, I do think it’s really important to think about the themes and continuities and lessons that we can really learn from history. And today’s episode has me thinking about political parties, and this kinda never-ending struggle that they have between what gets called party “unity,” or maintaining a “big tent,” and then on the other hand really trying to stick to or imagine more ambitious or even radical policy positions that vulnerable groups within the base of the party care about. -

ECONOMIC MAN Vs HUMANITY Lyrics

DOUGHNUT ECONOMICS PRESENTS . ECONOMIC MAN vs. HUMANITY: A PUPPET RAP BATTLE STARRING: Storyline and lyrics by Simon Panrucker, Emma Powell and Kate Raworth Key concepts and quotes are drawn from Chapter 3 of Doughnut Economics. * VOICE OVER And so this concept of rational economic man is a cornerstone of economic theory and provides the foundation for modelling the interaction of consumers and firms. The next module will start tomorrow. If you have any questions, please visit your local Knowledge Bank. POTATO Hello? BRASH Hello? FACTS Shall we go to the knowledge bank? BRASH Yeah that didn’t make any sense! POTATO See you outside. They pop up outside. BRASH Let’s go! They go to The Knowledge Bank. PROF Welcome to The Knowledge Ba… oh, it’s you lot. What is it this time? FACTS The model of rational economic man PROF Look, it's just a starting point for building on POTATO Well from the start, something doesn’t sit right with me BRASH We’ve got questions! PROF sighs. PROF Ok, let me go through it again . THE RAP BEGINS PROF Listen, it’s quite simple... At the heart of economics is a model of man A simple distillation of a complicated animal Man is solitary, competing alone, Calculator in head, money in hand and no Relenting, his hunger for more is unending, Ego in heart, nature’s at his will for bending POTATO But that’s not me, it can’t be true! There’s much more to all the things humans say and do! BRASH It’s rubbish! FACTS Well, it is a useful tool For economists to think our reality through It’s said that all models are wrong but some -

Contingent Election of the President and Vice President by Congress: Perspectives and Contemporary Analysis

Contingent Election of the President and Vice President by Congress: Perspectives and Contemporary Analysis Updated October 6, 2020 Congressional Research Service https://crsreports.congress.gov R40504 Contingent Election of the President and Vice President by Congress Summary The 12th Amendment to the Constitution requires that presidential and vice presidential candidates gain “a majority of the whole number of Electors appointed” in order to win election. With a total of 538 electors representing the 50 states and the District of Columbia, 270 electoral votes is the “magic number,” the arithmetic majority necessary to win the presidency. What would happen if no candidate won a majority of electoral votes? In these circumstances, the 12th Amendment also provides that the House of Representatives would elect the President, and the Senate would elect the Vice President, in a procedure known as “contingent election.” Contingent election has been implemented twice in the nation’s history under the 12th Amendment: first, to elect the President in 1825, and second, the Vice President in 1837. In a contingent election, the House would choose among the three candidates who received the most electoral votes. Each state, regardless of population, casts a single vote for President in a contingent election. Representatives of states with two or more Representatives would therefore need to conduct an internal poll within their state delegation to decide which candidate would receive the state’s single vote. A majority of state votes, 26 or more, is required to elect, and the House must vote “immediately” and “by ballot.” Additional precedents exist from 1825, but they would not be binding on the House in a contemporary election. -

Understanding Robert Lucas (1967-1981): His Influence and Influences

A Service of Leibniz-Informationszentrum econstor Wirtschaft Leibniz Information Centre Make Your Publications Visible. zbw for Economics Andrada, Alexandre F.S. Article Understanding Robert Lucas (1967-1981): his influence and influences EconomiA Provided in Cooperation with: The Brazilian Association of Postgraduate Programs in Economics (ANPEC), Rio de Janeiro Suggested Citation: Andrada, Alexandre F.S. (2017) : Understanding Robert Lucas (1967-1981): his influence and influences, EconomiA, ISSN 1517-7580, Elsevier, Amsterdam, Vol. 18, Iss. 2, pp. 212-228, http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.econ.2016.09.001 This Version is available at: http://hdl.handle.net/10419/179646 Standard-Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Die Dokumente auf EconStor dürfen zu eigenen wissenschaftlichen Documents in EconStor may be saved and copied for your Zwecken und zum Privatgebrauch gespeichert und kopiert werden. personal and scholarly purposes. Sie dürfen die Dokumente nicht für öffentliche oder kommerzielle You are not to copy documents for public or commercial Zwecke vervielfältigen, öffentlich ausstellen, öffentlich zugänglich purposes, to exhibit the documents publicly, to make them machen, vertreiben oder anderweitig nutzen. publicly available on the internet, or to distribute or otherwise use the documents in public. Sofern die Verfasser die Dokumente unter Open-Content-Lizenzen (insbesondere CC-Lizenzen) zur Verfügung gestellt haben sollten, If the documents have been made available under an Open gelten abweichend von diesen Nutzungsbedingungen die in der dort Content Licence (especially Creative Commons Licences), you genannten Lizenz gewährten Nutzungsrechte. may exercise further usage rights as specified in the indicated licence. https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/ www.econstor.eu HOSTED BY Available online at www.sciencedirect.com ScienceDirect EconomiA 18 (2017) 212–228 Understanding Robert Lucas (1967-1981): his influence ଝ and influences Alexandre F.S. -

AVSEC/COMM/5-WP/06 International Civil Aviation Organization

AVSEC/COMM/5-WP/06 International Civil Aviation Organization 31/03/06 CAR/SAM REGIONAL PLANNING IMPLEMENTATION GROUP (GREPECAS) Fifth Meeting of the GREPECAS Aviation Security Committee (AVSEC/COMM/5) Buenos Aires, Argentina, 11 to 13 May 2006 Agenda Item 4 Development of the AVSEC/COMM Work Programme 4.1 Hold Baggage Screening Task Force Developments (AVSEC/HBS/TF) GUIDANCE MATERIAL TO FACILITATE THE IMPLEMENTATION OF HOLD BAGGAGE SCREENING ON A GLOBAL BASIS (Presented by the International Air Transport Association [IATA]) SUMMARY In order for the ICAO requirement for 100% Hold Baggage Screening to be fully effective, technical screening methods must be used in conjunction with standardized procedures for all directly and indirectly involved in the process of Hold Baggage Screening. This paper present the IATA view on how best to implement 100% HBS and ensure that screening procedures are formalized in order to ensure that screening standards meet globally accepted standards. References: • IATA Position Paper on 100% Hold Baggage Screening (September 2003) (Appendix 1) 1. Introduction 1.1 The air transport industry operates in an extremely complex environment. In order to properly service their customers, air carriers must operate a multiplicity of routes, through numerous transfer and transit points involving numerous States, airports and often air carriers. 1.2 Superimposed on this already complex network are decisions made by individual States regarding the security and facilitation standards that they require within their territories as well as security and facilitation measures to be adopted by their registered air carriers when they operate in another State. This regulatory/operational environment has been made even more complex and difficult since the tragic events of 11 September, 2001. -

1 Paradise, for Sale: Hgtv's Caribbean Life and The

PARADISE, FOR SALE: HGTV’S CARIBBEAN LIFE AND THE POLITICS OF REPRESENTATION BY STEPHANIE DENARDO A THESIS PRESENTED TO THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF THE UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA 2017 1 © 2017 Stephanie Denardo 2 To my family, who first exposed me to new places and ideas 3 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I could not have completed this paper without the endless support, insights, and critiques from my chair and committee members, who pushed me beyond typical disciplinary boundaries to see the world through many lenses. 4 TABLE OF CONTENTS page ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS .............................................................................. 4 LIST OF TABLES ........................................................................................... 6 LIST OF FIGURES ........................................................................................ 7 ABSTRACT .................................................................................................... 9 CHAPTER 1 INTRODUCTION: HGTV AND THE VISUAL ESCAPE ......................... 10 2 LITERATURE REVIEW AND METHODOLOGY ................................... 13 Examining HGTV in North America ....................................................... 13 Representation and Identity Power Politics in IR ................................... 17 Paradise: Defining a Discourse and Its History ..................................... 21 Methodology: Critical Visual Discourse Analysis ................................... 24 3 -

House Md S06 Swesub

House md s06 swesub House M.D.. Season 8 | Season 7 | Season 6 | Season 5 | Season 4 | Season 3 | Season 2 | Season 1. #, Episode, Amount, Subtitles. 6x21, Help Me, 11, en · es. Greek subtitles for House M.D. Season 6 [S06] - The series follows the life of anti-social, pain killer addict, witty and arrogant medical docto. Hugh Laurie plays the title role in this unusual new detective series. Gregory House is an introvert, antisocial doctor any time avoid having any contact with their. House M.D. - 6x12 - Moving the Chainsp English. · House M.D. - 6x20 - English. · House M.D. House returns home to Princeton where he continues to focus on hi Sep 28, Harsh Lighting. Episode 3: The Tyrant. When a. Home >House M.D.. Share this video: House treats a patient on death row while Dr. Cameron avoids Sep 13, 44 Season 6 Show All Episodes. 20 House returns home to House M.D. Season 08 ﻣﺴﺤﻮﺑﺔ ﻣﻦ اﻟﻨﺖ" ,Princeton where he continues to focus Sep Arabic · House, M.D. Season 6 (p x Joy), 6 months ago, 1, B COMPLETE p BluRay x MB Pahe. House m d s06 swesub. No-registration upload files up MB claims there victim dying, but not from accident. House m d s06 swesub. Amd radeon hd g драйвер. House M.D. - Season 6: In this season, House finds himself in an And when House returns more obstinate. «House, M.D.» – Season 6, Episode 13 watch in HD quality with subtitles in different languages for free and without registration! «House, M.D.» – Season 6, Episode 2 watch in HD quality with subtitles in different languages for free and without registration! -Sabelma Romanian Subtitle. -

The Wealth Report

THE WEALTH REPORT A GLOBAL PERSPECTIVE ON PRIME PROPERTY AND WEALTH 2011 THE SMALL PRINT TERMS AND DEFINITIONS HNWI is an acronym for ‘high-net-worth individual’, a person whose investible assets, excluding their principal residence, total between $1m and $10m. An UHNWI (ultra-high-net-worth individual) is a person whose investible assets, excluding their primary residence, are valued at over $10m. The term ‘prime property’ equates to the most desirable, and normally most expensive, property in a defined location. Commonly, but not exclusively, prime property markets are areas where demand has a significant international bias. The Wealth Report was written in late 2010 and early 2011. Due to rounding, some percentages may not add up to 100. For research enquiries – Liam Bailey, Knight Frank LLP, 55 Baker Street, London W1U 8AN +44 (0)20 7861 5133 Published on behalf of Knight Frank and Citi Private Bank by Think, The Pall Mall Deposit, 124-128 Barlby Road, London, W10 6BL. THE WEALTH REPORT TEAM FOR KNIGHT FRANK Editor: Andrew Shirley Assistant editor: Vicki Shiel Director of research content: Liam Bailey International data coordinator: Kate Everett-Allen Marketing: Victoria Kinnard, Rebecca Maher Public relations: Rosie Cade FOR CITI PRIVATE BANK Marketing: Pauline Loohuis Public relations: Adam Castellani FOR THINK Consultant editor: Ben Walker Creative director: Ewan Buck Chief sub-editor: James Debens Sub-editor: Jasmine Malone Senior account manager: Kirsty Grant Managing director: Polly Arnold Illustrations: Raymond Biesinger (covers), Peter Field (portraits) Infographics: Leonard Dickinson, Paul Wooton, Mikey Carr Images: 4Corners Images, Getty Images, Bridgeman Art Library PRINTING Ronan Daly at Pureprint Group Limited DISCLAIMERS KNIGHT FRANK The Wealth Report is produced for general interest only; it is not definitive.