Native Painters of a European Book

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

El Oro De Tenochtitlan: La Colección Arqueológica Del Proyecto Templo Mayor Tenochtitlan’S Gold: the Archaeological Collection of the Great Temple Project

El oro de Tenochtitlan: la colección arqueológica del Proyecto Templo Mayor Tenochtitlan’s Gold: the Archaeological Collection of the Great Temple Project LEONARDO LÓPEZ LUJÁN Doctor en arqueología por la Université de Paris X-Nanterre. Profesor-investigador del Museo del Templo Mayor, INAH. Miembro del Proyecto Templo Mayor desde 1980 y su director a partir de 1991. Véase www.mesoweb.com/about/leonardo.html JOSÉ LUIS RUVALCABA SIL Doctor en Ciencias por la Université de Namur. Investigador del Instituto de Física de la UNAM. Director del Laboratorio de Análisis No Destructivo en Arte, Arqueología e Historia (ANDREAH) y del Laboratorio del Acelerador Pelletron. Véase www. fisica.unam.mx/andreah RESUMEN El territorio mexicano no es rico en yacimientos de oro nativo. Dicho fenómeno explica por qué las civilizacio- nes mesoamericanas aprovecharon este metal en cantidades siempre modestas. En este artículo se analiza la totalidad de la colección de oro del Proyecto Templo Mayor a la luz de la información histórica, arqueológica y química, con el fin de ofrecer nuevas ideas sobre su cronología, tecnología, tipología, función, significado, tradición orfebre y “zona geográfica de uso” en el Centro de México durante el Posclásico Tardío. PALABRAS CLAVE Tenochtitlan, recinto sagrado, Templo Mayor, Azcapotzalco, ofrendas, oro, orfebrería ABSTRACT Mexico is a not a country rich in native gold depos- its. This would explain why the precious metal was always used rather sparingly in Mesoamerican civilizations. This article will analyze the entire collection of gold pieces from the Great Temple Project in light of various historical, archaeological, and chemical data, and offer new insights about the chronology, typology, function, meaning, manufac- turing tradition, and “geographical area of use” of gold in Late Postclassic Central Mexico. -

Encounter with the Plumed Serpent

Maarten Jansen and Gabina Aurora Pérez Jiménez ENCOUNTENCOUNTEERR withwith thethe Drama and Power in the Heart of Mesoamerica Preface Encounter WITH THE plumed serpent i Mesoamerican Worlds From the Olmecs to the Danzantes GENERAL EDITORS: DAVÍD CARRASCO AND EDUARDO MATOS MOCTEZUMA The Apotheosis of Janaab’ Pakal: Science, History, and Religion at Classic Maya Palenque, GERARDO ALDANA Commoner Ritual and Ideology in Ancient Mesoamerica, NANCY GONLIN AND JON C. LOHSE, EDITORS Eating Landscape: Aztec and European Occupation of Tlalocan, PHILIP P. ARNOLD Empires of Time: Calendars, Clocks, and Cultures, Revised Edition, ANTHONY AVENI Encounter with the Plumed Serpent: Drama and Power in the Heart of Mesoamerica, MAARTEN JANSEN AND GABINA AURORA PÉREZ JIMÉNEZ In the Realm of Nachan Kan: Postclassic Maya Archaeology at Laguna de On, Belize, MARILYN A. MASSON Life and Death in the Templo Mayor, EDUARDO MATOS MOCTEZUMA The Madrid Codex: New Approaches to Understanding an Ancient Maya Manuscript, GABRIELLE VAIL AND ANTHONY AVENI, EDITORS Mesoamerican Ritual Economy: Archaeological and Ethnological Perspectives, E. CHRISTIAN WELLS AND KARLA L. DAVIS-SALAZAR, EDITORS Mesoamerica’s Classic Heritage: Teotihuacan to the Aztecs, DAVÍD CARRASCO, LINDSAY JONES, AND SCOTT SESSIONS Mockeries and Metamorphoses of an Aztec God: Tezcatlipoca, “Lord of the Smoking Mirror,” GUILHEM OLIVIER, TRANSLATED BY MICHEL BESSON Rabinal Achi: A Fifteenth-Century Maya Dynastic Drama, ALAIN BRETON, EDITOR; TRANSLATED BY TERESA LAVENDER FAGAN AND ROBERT SCHNEIDER Representing Aztec Ritual: Performance, Text, and Image in the Work of Sahagún, ELOISE QUIÑONES KEBER, EDITOR The Social Experience of Childhood in Mesoamerica, TRACI ARDREN AND SCOTT R. HUTSON, EDITORS Stone Houses and Earth Lords: Maya Religion in the Cave Context, KEITH M. -

The Venus-Rain-Maize Complex in the Mesoamerican World

JHA, xxiv (1993) 1993JHA....24...17S THE VENUS-RAIN-MAIZE COMPLEX IN THE MESOAMERICAN WORLD VIEW: PART I IVAN SPRAJC, Instituto Nacional de Antropologia e Historia, Mexico City INTRODUCTION The importance attributed to the planet Venus by the ancient Mesoamericans is well known. Most famous is its malevolent aspect: according to some written sources from the post-Conquest central Mexico, the morning star at its first appearance after inferior conjunction was believed to inflict harm on nature and mankind in a number of ways. Iconographic elements in various codices seem to confirm these reports. Although there is a considerable amount of data of this kind, some recent studies have revealed the inadequacy of the common assumption that the heliacal rise was the most, if not the only, important Venus phenomenon. It has been argued that "in spite of the obvious importance of the first appearance of the Morning Star ... , the Evening Star which disappears into inferior conjunction in the underworld had an equal, if not greater, signifi cance".1 The importance of the evening star and of events other than heliacal risings is also attested in Mayan inscriptions and codices.2 Consequently, the symbolism associated with the planet Venus in Mesoamerica must have been much more complex than is commonly thought. One part of this symbolism was related to rain and maize. 3 The conceptual association of the planet Venus with rain and maize can be designated, following Closs et al., as the Venus-rain-maize complex.4 The object of this study is to present various kinds of evidence to demonstrate the existence of this complex of ideas in Mesoamerica, to describe its forms and particularities associated with distinct aspects of the planet, to follow its development, and to explore its possible observational bases. -

Abhiyoga Jain Gods

A babylonian goddess of the moon A-a mesopotamian sun goddess A’as hittite god of wisdom Aabit egyptian goddess of song Aakuluujjusi inuit creator goddess Aasith egyptian goddess of the hunt Aataentsic iriquois goddess Aatxe basque bull god Ab Kin Xoc mayan god of war Aba Khatun Baikal siberian goddess of the sea Abaangui guarani god Abaasy yakut underworld gods Abandinus romano-celtic god Abarta irish god Abeguwo melansian rain goddess Abellio gallic tree god Abeona roman goddess of passage Abere melanisian goddess of evil Abgal arabian god Abhijit hindu goddess of fortune Abhijnaraja tibetan physician god Abhimukhi buddhist goddess Abhiyoga jain gods Abonba romano-celtic forest goddess Abonsam west african malicious god Abora polynesian supreme god Abowie west african god Abu sumerian vegetation god Abuk dinkan goddess of women and gardens Abundantia roman fertility goddess Anzu mesopotamian god of deep water Ac Yanto mayan god of white men Acacila peruvian weather god Acala buddhist goddess Acan mayan god of wine Acat mayan god of tattoo artists Acaviser etruscan goddess Acca Larentia roman mother goddess Acchupta jain goddess of learning Accasbel irish god of wine Acco greek goddess of evil Achiyalatopa zuni monster god Acolmitztli aztec god of the underworld Acolnahuacatl aztec god of the underworld Adad mesopotamian weather god Adamas gnostic christian creator god Adekagagwaa iroquois god Adeona roman goddess of passage Adhimukticarya buddhist goddess Adhimuktivasita buddhist goddess Adibuddha buddhist god Adidharma buddhist goddess -

Texto Completo (Pdf)

Ab Initio, Núm. 11 (2015) Marta Gajewska Tlazolteotl, un ejemplo… TLAZOLTEOTL, UN EJEMPLO DE LA COMPLEJIDAD DE LAS DEIDADES MESOAMERICANAS TLAZOLTEOTL, AN EXAMPLE OF THE COMPLEXITY OF THE MESOAMERICAN DEITIES Marta Gajewska Máster en Estudios Hispánicos (Universidad de Varsovia) Resumen. En este artículo se intenta Abstract. In this article we will try to demostrar que la clasificación de los demonstrate that the classification of dioses mesoamericanos en los complejos Mesoamerican gods in the complex of de las deidades simplifica la visión de deities simplifies the vision of each one cada uno de éstos en particular. A partir in particular. Based on the analysis of del análisis de las distintas funciones de Tlazoteotl’s various functions, we will la diosa Tlazolteotl se verificarán sus try to verify her different categorizations diferentes categorizaciones (telúrica, (telluric, lunar…), aiming to prove that lunar, etc.) y se demostrará que es una it was a deity with multiple meanings deidad de múltiples significaciones que which acquired along the centuries, adquirió a lo largo de los siglos según according to the needs that were las necesidades que iban surgiendo. appearing. Palabras clave: Tlazolteotl, deidades, Keywords: Tlazolteotl, deities, religión mesoamericana, iconografía, Mesoamerican religion, iconography, códice. codex. Para citar este artículo: GAJEWSKA, Marta, “Tlazolteotl, un ejemplo de la complejidad de las deidades mesoamericanas”, Ab Initio, Núm. 11 (2015), pp. 89-126, disponible en www.ab-initio.es Recibido: 30/05/2014 Aceptado: 31/03/2015 I. INTRODUCCIÓN Tlazolteotl, una de las deidades del centro de México, ha sido tradicionalmente identificada como la diosa de la inmundicia, de la basura y del pecado corporal. -

The Sanctuary of Night and Wind

chapter 7 The Sanctuary of Night and Wind At the end of Part 1 (Chapter 4) we concluded that Tomb 7 was a subterraneous sanctuary that belonged to a Postclassic ceremonial centre on Monte Albán and that this centre appears in Codex Tonindeye (Nuttall), p. 19ab, as a Temple of Jewels. Combining the archaeological evidence with the information from the Ñuu Dzaui pictorial manuscripts we understand that the site was of great religious importance for the dynasty of Zaachila, and particularly for Lady 4 Rabbit ‘Quetzal’, the Mixtec queen of that Zapotec kingdom. The depiction in Codex Tonindeye confirms that this sanctuary was a place for worship of sa- cred bundles but it also indicates that here the instruments for making the New Fire were kept. The Temple of Jewels, therefore, combines a religious fo- cus on the ancestors with one on the cyclical renewal of time. Continuing this line of thought, in Part 2 we explore the historical and ide- ological importance of that ritual. This has led us to discuss the meaning of several other ancient Mesoamerican artefacts, codices and monuments, such as the Roll of the New Fire (Chapter 5) and representations of rituals in Aztec art (Chapter 6). With these detailed case studies, we now confront the chal- lenge to try to say something more about the type of rituals that took place in the Temple of Jewels, so we can get an idea of the religious value of Tomb 7 and the religious experiences that ritual practice entailed. Fortunately, the representations of rituals and their associated symbolism in precolonial picto- rial manuscripts, particularly those of the Teoamoxtli Group (Borgia Group), allow us to reconstruct some of the Mesoamerican ideas and visionary experi- ences. -

The Fertilizing Role of Monkey Among Ancient Nahuas Jaime Echeverría Garc

Entre la fertilidad agrícola y la generación humana: el rol fecundante del mono entre los antiguos nahuas Between agricultural fertility and human generation: the fertilizing role of monkey among ancient Nahuas JAIME ECHEVERRÍA GARCÍA Jaime Echeverría García es doctor en Antropología por el Instituto de Investigaciones Antropológicas de la UNAM. Es miembro del Sistema Nacional de Investigadores (nivel 1). Sus principales líneas de investigación son la locura, la alteridad y el miedo entre los nahuas prehispánicos. Entre sus publica- ciones se encuentran Los locos de ayer. Enfermedad y desviación en el México antiguo, Extranjeros y marginados en el mundo mexica y “Tonalli, naturaleza fría y personalidad temerosa: el susto entre los nahuas del siglo XVI”. RESUMEN En este artículo estudio los simbolismos de fertilidad, procrea- ción y abundancia atribuidos al mono entre los antiguos nahuas, los cuales fueron proyectados hacia los ámbitos agrícola y humano. De forma sobresaliente, la figura del simio intervino en el buen desarrollo del ciclo agrícola, desde el cultivo de la semilla hasta la cosecha del fruto maduro, así como en la reproducción humana. De esta manera, el mono estuvo presente en sitios rurales, durante el parto, en el culto a los cerros, a los dioses de la lluvia y del pulque, entre otros contextos. La metodología que se siguió fue la vinculación del dato arqueológico, el histórico y, en menor medida, el etnográfico. PALABRAS CLAVE nahuas, mono, fertilidad, procreación, cosmovisión ABSTRACT In this article I study the symbolisms of fertility, procreation and abundance attributed to monkey among ancient Nahuas, which were projected toward the farm and human spheres. -

Proto-Orthography in the Codex Borbonicus

HOW DRAWING BECOMES WRITING: PROTO-ORTHOGRAPHY IN THE CODEX BORBONICUS Taylor Bolinger Thesis Prepared for the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS UNIVERSITY OF NORTH TEXAS May 2013 APPROVED: John ‘Haj’ Ross, Major Professor Timothy Montler, Minor Professor Jongsoo Lee, Committee Member Brenda Sims, Chair of the Department of Linguistics and Technical Communication Mark Wardell, Dean of the Toulouse Graduate School Bolinger, Taylor. How Drawing Becomes Writing: Proto-Orthography in the Codex Borbonicus. Master of Arts (Linguistics), May 2013, 84 pp., 19 tables, 59 illustrations, references, 51 titles. The scholarship on the extent of the Nahuatl writing system makes something of a sense-reference error. There are a number of occurrences in which the symbols encode a verb, three in the present tense and one in the past tense. The context of the use of calendar systems and written language in the Aztec empire is roughly described. I suggest that a new typology for is needed in order to fully account for Mesoamerican writing systems and to put to rest the idea that alphabetic orthographies are superior to other full systems. I cite neurolinguistic articles in support of this argument and suggest an evolutionary typology based on Gould's theory of Exaptation paired with the typology outlined by Justeson in his "Origins of Mesoamerican Writing" article. Copyright 2013 by Taylor Bolinger ii CONTENTS Page LIST OF TABLES AND FIGURES ......................................................................................................... iv CHAPTER 1 INTRODUCTION -

Los Dioses Mexicas Y Los Elementos Naturales En Sus Atuendos: Unos Materiales Polisémicos Trace

Trace. Travaux et Recherches dans les Amériques du Centre ISSN: 0185-6286 [email protected] Centro de Estudios Mexicanos y Centroamericanos México Vauzelle, Loïc Los dioses mexicas y los elementos naturales en sus atuendos: unos materiales polisémicos Trace. Travaux et Recherches dans les Amériques du Centre, núm. 71, enero, 2017, pp. 76-110 Centro de Estudios Mexicanos y Centroamericanos Distrito Federal, México Disponible en: http://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=423850280004 Cómo citar el artículo Número completo Sistema de Información Científica Más información del artículo Red de Revistas Científicas de América Latina, el Caribe, España y Portugal Página de la revista en redalyc.org Proyecto académico sin fines de lucro, desarrollado bajo la iniciativa de acceso abierto Los dioses mexicas y los elementos naturales en sus atuendos: unos materiales polisémicos SECCIÓN SECCIÓN TEMÁTICA Aztec gods and natural elements in their outfits: a few polysemous materials Loïc Vauzelle* Fecha de recepción: 26 de julio de 2016 • Fecha de aprobación: 21 de octubre de 2016. Resumen: Los atavíos de los dioses mexicas estaban hechos con diversos elementos na- turales, aunque tal variedad no impedía que un mismo material se utilizara para fabricar objetos diferentes. Se tiene en cuenta el hecho de que los atavíos de los dioses tenían una significación relacionada con sus campos de acción, este artículo examina sus modalidades de uso y sus símbolos. Se analizan dos elementos particulares: las plumas de garceta blanca y el oro, los cuales revelan que la polisemia es un concepto central en los adornos de los dioses y que dos principios, al menos, permiten distinguir los diferentes simbolismos asociados con un mismo material: o el tipo de atavío llevado puede influenciar en su significación, o son las combinaciones de elementos naturales —enlazados y formando un conjunto de atavíos— las que son significativas. -

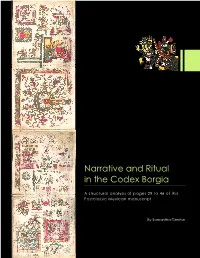

Narrative and Ritual in the Codex Borgia

Narrative and Ritual in the Codex Borgia A structural analysis of pages 29 to 46 of this Postclassic Mexican manuscript By Samantha Gerritse Narrative and Ritual in the Codex Borgia A structural analysis of pages 29 to 46 of this Postclassic Mexican manuscript Samantha Gerritse Course: RMA thesis, 1046WTY, final draft Student number: 0814121 Supervisor: Prof. Dr. M.E.R.G.N. Jansen Specialization: Religion and Society Institution: Faculty of Archaeology Place and date: Delft, June 2013 Contents. Acknowledgements p. 5 I. 1. Introduction p. 6 1.1 General research problem p. 6 1.2 The Codex Borgia p. 7 1.3 Problems with pages 29 to 46 of the Codex Borgia p. 10 1.2 Research aims and questions p. 11 2. Mesoamerican Religion p. 13 2.1 Worldview p. 13 2.2 Calendars p. 17 2.3 Priests and public rituals p. 19 2.4 Divination p. 21 3. Theoretical Framework p. 24 3.1 Interpretation by analogy p. 24 3.2 Interpretation by narratology p. 27 4. Methodology p. 32 4.1 Analysis of the interpretations p. 32 4.2 Analysis through narratology p. 33 II. 5. Iconographical interpretations of pages 29 to 46 p. 36 5.1 An overview p. 36 5.1.1 Fábrega (1899) p. 38 5.1.2 Seler (1906; 1963) p. 41 5.1.3 Milbrath (1989) p. 49 5.1.4 Nowotny (1961; 1976; 2005) p. 55 5.1.5 Anders, Jansen, and Reyes García (1993a) p. 61 5.1.6 Byland (1993) p. 70 5.1.7 Boone (2007) p. -

The Deity As a Mosaic: Images of the God Xipe Totec in Divinatory Codices from Central Mesoamerica

Ancient Mesoamerica, page 1 of 27, 2021 Copyright © The Author(s), 2021. Published by Cambridge University Press. This is an Open Access article, distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives licence (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/), which permits non-commercial re-use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is unaltered and is properly cited. The written permission of Cambridge University Press must be obtained for commercial re-use or in order to create a derivative work. doi:10.1017/S0956536120000553 THE DEITY AS A MOSAIC: IMAGES OF THE GOD XIPE TOTEC IN DIVINATORY CODICES FROM CENTRAL MESOAMERICA Katarzyna Mikulska Institute of Iberian and Iberoamerican Studies, University of Warsaw, ul. Krakowskie Przedmies´cie 26/28, 00-927 Warsaw, Poland Abstract In this article I argue that the graphic images of the gods in the divinatory codices are composed of signs of different semantic values which encode particular properties. All of them contribute to creating the identity of the god. However, these graphic elements are not only shared by different deities, but even differ between representations of the same god. Analyzing the graphic images of Xipe Totec, one of the best-studied deities and one of the oldest in Mesoamerica, I elaborate a hypothesis that the images of the gods in the divinatory codices were perceived by their authors as a mosaic of different properties, which at the same time were dynamic. Consequently, there was not even one “prototypical” representation of a single god, since possibly the identity of a god was defined precisely when composing his/her image with particular graphic signs, thus crystallizing some of his/her multiple properties, important at this precise moment. -

Baquedano2014.Pdf

Te z c a t l i p o c a Te z c a t l i p o c a Trickster and Supreme Deity edited by Elizabeth Baquedano UNIVERSIT Y PRESS OF COLORADO Boulder © 2014 by University Press of Colorado Published by University Press of Colorado 5589 Arapahoe Avenue, Suite 206C Boulder, Colorado 80303 All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America Te University Press of Colorado is a proud member of the Association of American University Presses. Te University Press of Colorado is a cooperative publishing enterprise supported, in part, by Adams State University, Colorado State University, Fort Lewis College, Metropolitan State University of Denver, Regis University, University of Colorado, University of Northern Colorado, Utah State University, and Western State Colorado University. ∞ Tis paper meets the requirements of the ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992 (Permanence of Paper). ISBN: 978-1-60732-287-0 (cloth) ISBN: 978-1-60732-288-7 (ebook) Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Tezcatlipoca : trickster and supreme deity / [edited by] Elizabeth Baquedano. pages cm ISBN 978-1-60732-287-0 (hardback) — ISBN 978-1-60732-288-7 (ebook) 1. Tezcatlipoca (Aztec deity) 2. Aztecs—Religion. 3. Aztec mythology. I. Baquedano, Elizabeth. F1219.75.R45T49 2014 299.7'138—dc23 2013035024 23 22 21 20 19 18 17 16 15 14 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 Cover illustration: Tezcatlipoca holding two fint knives, from the Codex Laud. To the memory of my beloved father and sister. To the memory of our dear friends and mentors Beatriz de la Fuente, Doris Heyden, and H.